[No intro needed, although a stinging editorial would be in order about the appalling decision of executive producer Adam McKay and his colleagues to dramatize Jerry West as a drunken, raving general manager in the series Winning Times: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty, now airing mostly to collective groans on HBO.

McKay has taken West and his larger-than-life, 60-plus-year legend and shoehorned it into his sophomoric caricature, in his own words, of “an era when mental health barely existed, sex & blow were everywhere, ppl barely blinked at racism & sexism & the NBA went from a failing league to the coolest thing almost overnight.”

Seriously? Though McKay did grow up during the 1980s, he clearly missed quite a lot about the decade’s underlying cultural complexity, from the rise of neoliberalism and born-again religion to campus protests against apartheid, nuclear proliferation, and, yes, racism and sexism. What was McKay thinking taking on Mom, apple pie, and Jerry West? It’s pure hubris that’s sparked a public outcry and debate that he and his HBO colleagues can’t win, nor should they.

In my view, the Lakers’ Winning Times would work just fine dramatically without dragging the 83-year-old Jerry West through the mud of McKay’s crass generalizations. It’s not fair to West, nor is fair to basketball history to tell tales spun mostly from whole cloth. I’ll leave it there. No more head shaking. Back to the article, written by veteran reporter Bert Rosenthal, covering the years leading up to those winning times in the 1980s. It appeared in the magazine All-Star Sports’ 1977-78 Basketball Issue.]

****

“I want to win.”

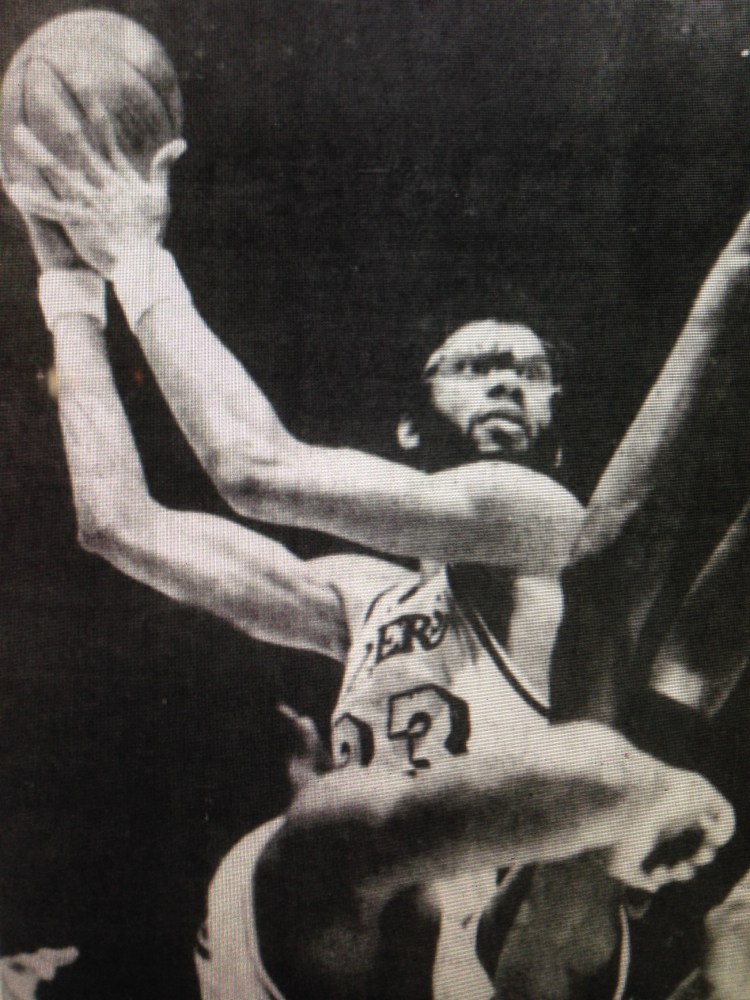

With these few words, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a sometimes-complex man, expressed simply his feelings, along with those of virtually every player in the National Basketball Association and, for that matter, in all of sports.

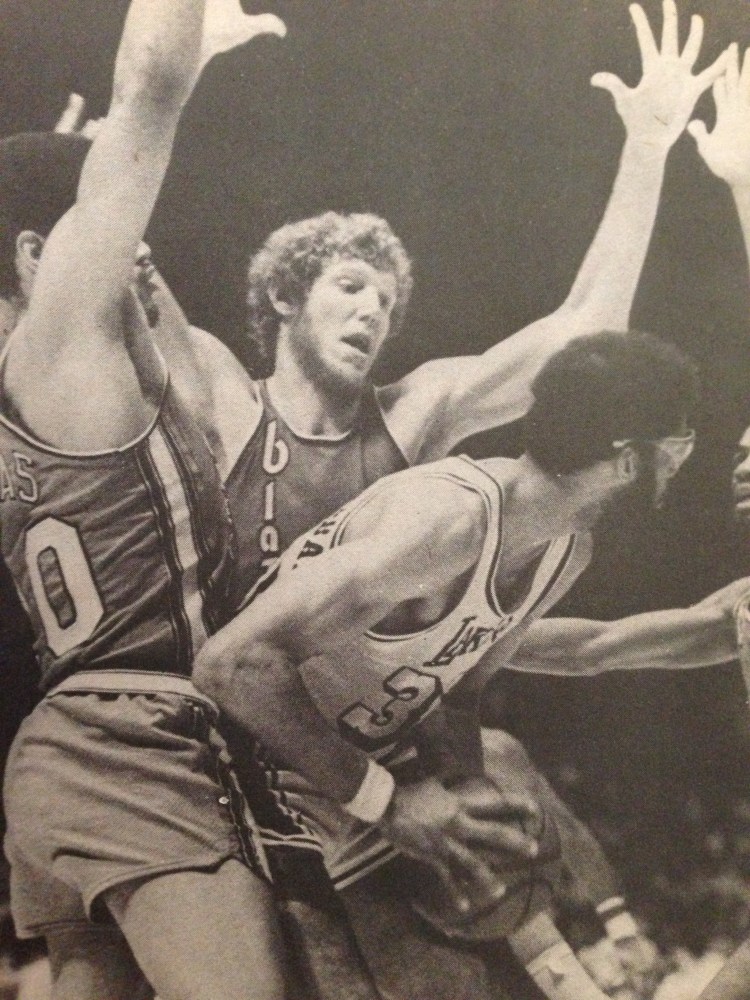

For the true athlete, winning is paramount. And in team sports, it transcends individual accomplishments. The Portland Trail Blazers were a prime example of what a disciplined team could accomplish, winning the NBA championship last season by beating the more-talented, but more-individualistic, Philadelphia 76ers in the final series. Portland has proven—just like the Golden State Warriors had done in the 1974-75 season—that it was not necessary for a team to have a group of superstars in order to win the title.

En route to winning the championship, in their first appearance in the playoffs in their seven-year history, the Trail Blazers eliminated Abdul-Jabbar in the Los Angeles Lakers, four games to none, for the Western Conference title.

Not only was the defeat embarrassing for Kareem and the Lakers, after they had compiled the best regular-season record (53-29, compared to Portland’s 49-33), it was frustrating for Abdul-Jabbar, the game’s most-dominating player.

The loss made his runaway selection as the NBA’s most valuable player—the fifth time in the past seven years he had won the award—seem almost like a consolation prize. It also overshadowed the fact that he had won the field-goal percentage title for the first time in his career (at .579), and that he was third in scoring (26.2), second in rebound average (13.3), first in defensive rebounds (824), and second in blocked-shot average (3.18). And it was of little consequence that he had joined Bill Russell, the ex-Boston Celtic great, as the only five-time winner of the Podoloff Trophy, named after Maurice Podoloff, the league’s first commissioner.

Instead, it heightened the pressure on the Lakers’ 7-foot-3 ½ center to prove that he is a winner in the mold of Russell, who led the Celtics to 11 NBA championships in 13 years. Of course, it must be pointed out that Russell had much superior supporting casts at Boston, working with such stars as Bob Cousy, Bill Sharman, Tommy Heinsohn, Frank Ramsey, and the Jones boys—Sam and K.C.—than Abdul-Jabbar has had in his six seasons with Milwaukee and two with Los Angeles.

Nevertheless, Kareem’s teams have produced only one league championship—in the 1970-71 season, his second with the Bucks. His lack of complete success each passing season is beginning to draw comparisons with another giant of the game: Wilt Chamberlain. He won only two championships in his 14 awesome seasons in the league—with Philadelphia in 1966-67 and Los Angeles in 1971-712.

Perhaps it is an unfair condemnation against Abdul-Jabbar, saying that he is not a winner, or that he is unable to lead a team to a championship, because of the players he has been surrounded with at Milwaukee and Los Angeles. But the fact remains that he has been instrumental in taking his team to a title only once in eight seasons, a very poor percentage for such an outstanding player. And because he is such a giant of the game—both literally and figuratively—much of the burden of proof unfortunately falls on him, just like it did on Chamberlain.

It can be argued, and rightly so, that Kareem took the Lakers much further than they had any business going last season. But once they got there—first place in the Pacific Division—the complexion changed. The Lakers, with the homecourt advantage in every series they would play (a tremendous asset because Los Angeles had amassed a 37-4 home court record, the best in the league), were considered favorites to at least sweep through the West.

However, Kareem and his teammates again came up short. After outlasting Golden State in seven games in the West semifinals, they were humiliated by the Trail Blazers in the final.

Meanwhile, Coach Jerry West came to Kareem’s defense and, at the same time, rapped some of the other players. “No, this is absolutely not the team I wanted,” West said of the club he inherited in his first year as coach. “What I’d keep are the togetherness and enthusiasm. But this is basically the same team as last year (1975-76, when the Lakers didn’t even make the playoffs), except for a few free agents.”

“Kareem is the best,” continued West. “He is the most-dominating player in the game. And he had a tremendous burden, because he was expected to do more than anybody in the league—score, rebound, block shots.

“He’s a magnificent center and a magnificent person,” added the former Lakers’ star, who appreciated Abdul-Jabbar much more when he had him on his team than when he played against him. “He did everything I asked. He played as well, day in and day out, as I could have possibly hoped for. Unselfish and sacrifice—that’s Kareem.

“Also, he was totally cooperative, and when younger players saw a star like him so cooperative, it had to help the team,” said West. “There is a good chemistry here, and Kareem definitely was a major part of it.

“We expected a lot from him, and he produced. Every time he went out there, he was double and triple-teamed, and it got awfully frustrating. But he never stopped working.”

After the season, West and his predecessor, Bill Sharman, now the Lakers’ general manager, quickly began remodeling the team. They sent unhappy, phlegmatic guard Lucius Allen to Kansas City for rebounding forward Ollie Johnson, shuffled unpredictable guard Johnny Neumann back to Buffalo, and signed their three first-round draft choices: forward Kenny Carr from North Carolina State, and guards Brad Davis from Maryland and Norm Nixon from Duquesne.

West, Kareem’s third professional coach, appeared to be his favorite. “Jerry West is one clever dude,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “He was responsible for making us a unified group. And that was the big difference in this team.”

“And as a coach,” Kareem continued, “Jerry West is easier to accept than Bill Sharman was because, as a person, he is easier to know, easier to talk to. He also brought in two assistant coaches—one for offense (Stan Albeck) and one for defense (Jack McCloskey). It worked really well. It was more like a football situation, but when the game started, Jerry was in charge.

“Also, Jerry coordinated the talent a whole lot better. He saw a lot we could do, and he saw a lot we couldn’t do. We have better balance now and better matchups.”

Under West, the Lakers ran a more-disciplined offense than they did under Sharman. There were more set plays, and each man in the offense had a specific role. “I didn’t really believe something like this could happen,” West said after the Lakers had clinched the division title. “Basically, we were a collection of misfits no one else wanted. But they all had individual talents, and they played well together.

“The players . . . had a very special kind of charisma for one another, an excellent chemistry . . . I believe our team played up to its potential more nights than any other team in the league this year.”

As for Kareem’s first coach, Larry Costello, Abdul-Jabbar often criticized his structured techniques. “Larry was right out of General Patton,” he said. “In Milwaukee, a lot of talented players worried more about doing Larry’s plays right than about playing basketball. Larry was from a different—how can I say it?—his views and attitudes were very different from Jerry’s.”

Even though Kareem was the league’s MVP in his one season under Sharman, he played with considerably more exuberance and enthusiasm under West in their first season. Under Sharman, while the Lakers were floundering, Kareem was asked to explain his team’s problems. He replied curtly: “Don’t ask me. I just get paid to come down and shoot a few hook shots every night.”

Under West, Kareem was reinvigorated, because his coach made the game fun again. “I think,” West explained, “the most-important thing about being a coach is making it as much fun as you possibly can. I think basketball is basically a kid’s game, except you have adults playing it.

“My philosophy is basically to have fun at what you’re doing. If you don’t have fun doing what you’re doing, then you shouldn’t be doing it.”

West’s philosophy obviously rubbed off on Kareem. “I’m happy again,” said Abdul-Jabbar. “Winning makes me happy. It’s what made Milwaukee tolerable (otherwise, he found the city intolerable because it was not culturally rewarding; that’s one of the major reasons he finally asked to leave).

“Last year (1975-76 under Sharman), we never got anything done. I was not optimistic in the preseason (of the 1976-77 campaign). But Jerry came in and organized, which I could not anticipate. Without arrogance, he was frank in what he wanted to do. You look at our team, and you’re not impressed. We got the type of players . . . well, people go to sleep on us.”

Not many people went to sleep on the Lakers last season, not when they realized that Los Angeles had become a consistent winner and the reclamation job West was doing.

In addition to refiring Kareem’s juices, West took forward Cazzie Russell out of the doghouse, re-instilled in him the confidence he had lost under Sharman and made him a vital part of the starting unit; outlined forward Don Ford’s responsibilities, making him basically a rebounding and defensive player; gave Lucius Allen the jobs of playmaker and scoring guard; entrusted Don Chaney with defensing the big guards on opposing teams; made rugged Kermit Washington his valuable “sixth” man; got rookie hotshot guard Earl Tatum from Marquette to curb his wild shooting habits; and explained to the other reserves, such as Johnny Neumann, Dwight Lamar, rookie Tom Abernethy from Indiana and C.J. Kupec, the exact roles he expected them to fill.

“The biggest surprise to me, was the fact that I had patience,” said West, a noted perfectionist. “In the past, I really didn’t have that with myself, nor with other people that I played with. Sometimes, you can mask that when you play. If I had an attribute, it was the fact that I was patient with the people we had.”

“I couldn’t look him in the eye at first,” confessed Tatum, whose frequent rookie mistakes might have caused West to throw himself in front of a car on the Los Angeles freeway in the past. “Now I got to.”

“Everybody knows what’s expected of him, and that’s made for a good atmosphere,” observed West.

When the Lakers’ owner Jack Kent Cooke first asked West if he was interested in the job, he said he was uncertain. “After all, when you’re thinking about starting something new for which you’ve had no formal training, you have to have a few reservations,” he explained. “I had absolutely no coaching experience, and I had to ask myself if I could go in there and make sense to the people I’d be dealing with.”

So, after some deep thinking and careful consideration, the Lakers’ one-time All-Star guard decided to return to the team, only two seasons after tearfully announcing his retirement as a player, signing a multi-year contract as coach.

Undoubtedly, one of the reasons he decided to take the job was the knowledge that he had one of the most solid foundations to build upon in his towering center. “He’s the most unselfish, cooperative star I’ve ever seen,” West said of the quiet, emotionless, enigmatic Abdul-Jabbar. “He’s a lot more than a basketball player, and he’s tremendously bright. His playing time was down from over 40 to less than 38 minutes, and his scoring went from over 30 points a game to less than 27.

“It had to help the attitude of the other players knowing that they would get to play with him. He doesn’t beat you by himself, even though he might on some nights. I don’t know how he does it with four guys keying on him. They might as well legalize zones because that’s all we see, and I wish the officials would notice what is done to him underneath, how he gets pushed and shoved.”

The roughness is one of the few things that disturbs Kareem about the game. “They (the NBA and the officials) have taken a large degree of the finesse out of the sport,” he said. “I just don’t think they want it to be an offensive game, and I’ll never understand it because people like to see scoring. How does it hurt the game?

“Dr. (Robert) Kerlan told me that my elbow, which flares up occasionally, is like a football player’s. That means I’ve been playing football, when I’m supposed to be playing basketball.”

One of the few times Kareem outwardly showed his anger last season was in the final playoff game against Golden State—and it cost the Warriors. With the Lakers playing lethargically and trailing 32-18 two minutes into the second quarter, rookie center Robert Parish of the Warriors popped an elbow into Abdul-Jabbar’s face.

Whether it was accidental or not, Kareem reacted quickly. He whipped off the protective mask he wears over his glasses and angrily threw the ball out of bounds. Then, he and Parish squared off, but were separated before any damage could be done.

However, the incident awakened Kareem and the Lakers. Abdul-Jabbar fired in 10 points in the next 10 minutes, helping the Lakers take a 48-46 halftime lead, and they went on to trounce the Warriors 97-84, behind Kareem’s 36-point, 26-rebound performance.

Kareem was nearly as devastating in the West final against Portland. But the Trail Blazers had more balance and ended the Lakers’ bid for their first championship since the 1971-72 season, when they had won with Jerry West, Wilt Chamberlain, and Elgin Baylor.

Afterward, Maurice Lucas, Portland’s power forward, expressed his admiration for Kareem. “He might be the most-respected player in the league,” said Lucas. “He seems to have such inner strength. You may beat his team, but you never beat him.”

And West certainly did not concede that, although the Trail Blazers had won, Portland’s Bill Walton was a better center. “Bill Walton is a great center, and he certainly had a great year,” said West. “But he is only the second-best center in basketball. Kareem is the best.”

“I don’t think I can play with any more consistency,” said Abdul-Jabbar about his 1976-77 season. “Once a player reaches his late 20s or early 30s (he is 30), his physical ability and knowledge of the game begin to mesh. That’s when a player is at his peak.

“Since I’ve been in Los Angeles, I believe I’ve been getting the most out of my potential. I’ve matured as a player, and that’s the most important part of anybody’s development. I have more understanding of the game. The little things you have to do well. When to switch, when not to. When to pass, when to hold the ball.”

“Kareem is the best center in the league,” said Bob McAdoo of the New York Knicks, echoing the sentiments of Lucas and West. “He is the hardest in the league to stop. You can’t let him get the position he wants—or you’re dead.”

“I think I’m one of the best,” Kareem said matter-of-factly. “Whoever is best is a matter of opinion. I’m glad some people think I’m best. I’m proud of that.”

Kareem also is proud of his attitude toward the game. “I never try to psych myself for games,” he explained. “I try to maintain a consistency of performance. If you try to get up for every game, you’ll become neurotic.”

It has been a tribute to a 7-foot-3 ½ Black Muslim that he has been able to escape neurosis, especially in a profession in which he is so often under the microscope. Of course, it has been advantageous that he likes what he is doing and has done so well at his job.

“I like the sport, which is very important,” he noted. “When you’re just looking to see that you get paid on time, that’s a very unprofessional attitude and that’s when it’s time to reconsider . . . anyone with that attitude ought to get out of the game.

“The game has been very good to me. I’d be a fool if I didn’t admit it. It’s kept my body in good shape, and it has rewarded me very well financially (he now is starting the third year of a five-year contract, estimated at $500,000 per season).

“And the free time means a lot to me. A season’s work suits me, too, in that there’s a long vacation. It’s a whole lot better than nine to five.”

The traveling aspect of professional basketball, which many players have found distasteful, however, has not perturbed Kareem to any great extent. “It wears you out,” he explained about the numerous trips each team takes during a season, “but I’ve been doing it so long, it’s become second nature. It’s just part of living now.

“And there are certain aspects of the travel I like. I see my family in New York, and I get to see different friends I’ve made around the country. I get to see what’s going on [in America]. And it allows me to collect a few things, like Persian rugs, which I like very much.”

Basketball, however, still is uppermost in his mind. “When you’re involved in something as emotional as basketball, concentration is a big factor,” he pointed out. “It becomes taxing on you mentally. You have to work to concentrate.

“But it’s not really as difficult as people might think,” he continued. “You don’t do anything else. I just worry about playing my game. It’s a lot of work, and it’s not something you can take for granted. If you play on weekends at the ‘Y,’ it’s a game. Playing in the NBA isn’t.”

No, it is a profession, a job that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar takes very seriously and participates in with enormous pride. That’s why he is so anxious to win another championship.

Enjoyed the article. One minor correction. The Bucks won the title in 1970-71. The Knicks won in 1969-70.

LikeLike

Thanks, K, that one got past me. I transcribe the articles, and, yes, I have to keep my eyes peeled for original editing errors. Thanks again.

LikeLike