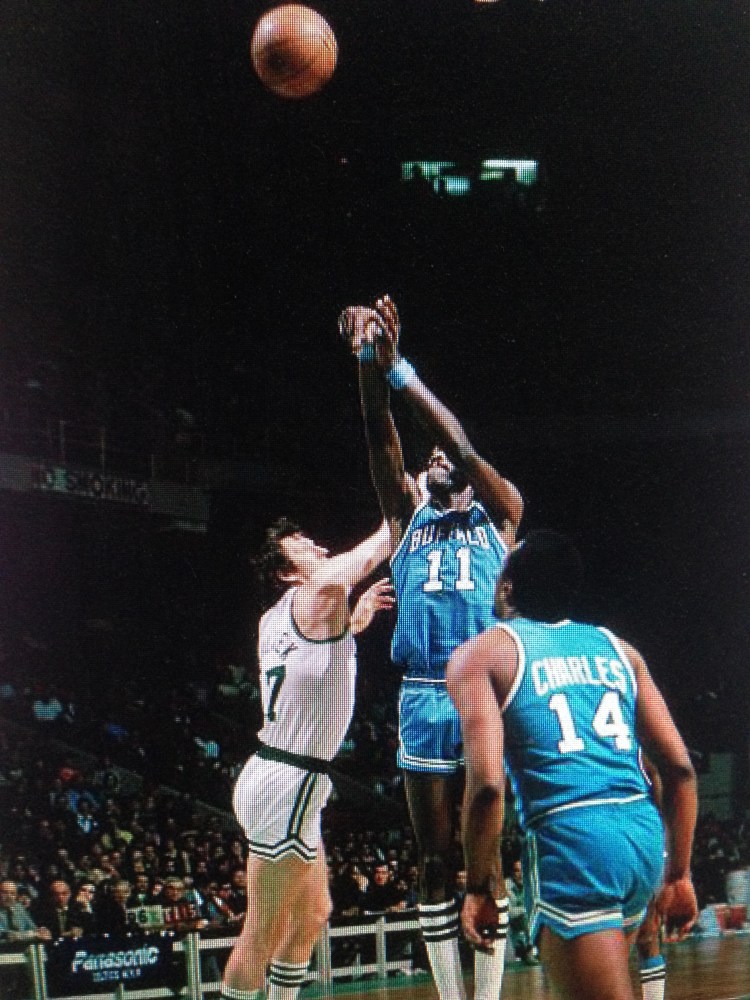

[Here’s a profile of the phenomenal Bob McAdoo entering in his fourth NBA season with the Buffalo Braves. The late Larry Bortstein penned the article for the magazine Pro Basketball Illustrated, 1975-76, with lots of black-and-white photos of McAdoo in action. Note: Some basketball magazines from the 1960s and 1970s are pretty poorly edited. There’s no other way to say it. This magazine is definitely a case in point, and I took a few liberties to fix some mangled sentences. However, if you like McAdoo, Bortstein wrote a good article, one that’s still worth reading today.]

****

During all the years of professional basketball, centers have won a great number of league scoring championships. This isn’t surprising in the case of men like Wilt Chamberlain and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who can score points by the bushel-full because of their close proximity to the basket when they let fly with their short jumpers or close-in hooks or tap-ins of missed shots.

But Bob McAdoo of the Buffalo Braves, who has captured the scoring championship of the National Basketball Association the past two seasons, is not cast from the traditional mold. The 6-foot-10 Braves’ pivotman piles up plenty of his points from distant areas where most self-respecting pro centers would never dream of roaming, much less shoot from. Big Mac fires them home from all over, and he does it often and relentlessly.

Tom Heinsohn, coach of the Boston Celtics, offered what is probably the most vivid description of Bob’s shooting ability after the Buffalo center nearly wrecked the Celtic club single-handedly in a playoff game not long ago. Said Heinsohn, “The bleep never misses.”

Well, McAdoo does miss sometimes. But it’s no accident that he is probably the finest shooting big man pro basketball ever has seen. As a young man, he practically was forced to become a great outside shooter.

As he tells the story, Bob was a tall, thin youngster hanging around the playgrounds in his hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina, at the age of 10. He was much bigger than the other boys around him, and he was the object of repeated and vicious taunts from the smaller ones.

“When we played basketball, I would eat those guys up,” he recalls. “Wham! All I had to do was go under the basket and slam the ball in. But the other guys used to say I couldn’t play ball. They said I was a big goon. They said that if I was their size, they’d beat me. They said a big man couldn’t shoot from outside. So, I said to myself, ‘Why can’t a big man shoot from outside, same as a little guy?’ So, I started practicing my outside shooting every day for as long as I could.

“After a while,” Bob continues, “I would go down to the playgrounds and beat the other guys from the outside. I wouldn’t even go under the basket, even when I had a chance. I’d say, ‘See, if I were your size, I’d shoot your pants off.’ It wasn’t that I needed to shoot, but it was a matter of pride. I wasn’t gonna have anybody say I was just a big goon. I was given my height by nature, and I’m not ashamed of it. I wanted to show I could beat other guys in basketball in all phases of the game, even those areas where small guys generally do better than big guys.”

Small guys and big guys alike throughout the NBA marvel at Mac’s shooting range and consistency with his jump shot. Unlike many centers, he eschews the use of the hook shot. “I don’t need it,” he says without false modesty. Rivals agree that Bob is doing fine just the way he is. “I’ve never seen a better outside threat,” says Boston’s John Havlicek.

Last year, Big Mac led the Braves to the finest season in their brief history and averaged 34.5 points per game to lead the NBA for the second successive year. In 1973-74, Bob topped the league with a 30.6 scoring norm and also a .547 field goal percentage. Only two other players ever have captured both honors in the same season—Chamberlain and Abdul-Jabbar, both of whom took the vast majority of their shots virtually on top of the basket.

But of all the awards Mac has won, or is likely to win, the one he cherishes most highly is the Podoloff Trophy, which he received as the NBA’s Most Valuable Player for his sensational performance a year ago [1975]. This included a .512 field goal percentage and an average of 14.1 rebounds and 2.12 block shots per game.

“I was really thrilled when I got the award,” he says. “It was like a dream come true.” McAdoo far outdistanced Boston’s Dave Cowens in the 1975 MVP voting. His fellow NBA players gave him 81 first-place votes to 32 for the Celtics’ redheaded center.

“What made winning the MVP so great,” Bob says, “is that I was a high school and college kid just a few years ago, and now the players I heard about and read about think I’m the best. And that’s an honor, man.”

McAdoo is sensitive about winning honors and awards. Though his maturity as an adult has helped him overcome his early disappointments, Bob feels he wasn’t treated fairly in the awards category during his earlier seasons in basketball.

“I seem to have been deprived of a lot of honors I feel I deserved,” he says without bitterness. “For example, in 1970, I helped my team at Vincennes Junior College (Indiana) win the national junior college championship. I was the leading scorer in the final tournament. But I wasn’t even named to the all-tournament team. I couldn’t believe it, since I did as much as anyone could have asked . . . and I had the most points in the championship game.

“Then, when I played one year at the University of North Carolina, I helped us win the conference championship, and we went to the semifinals of the NCAA tournament. But Barry Parkhill of Virginia was named the Most Valuable Player in the Atlantic Coast Conference. In my second year in the NBA, when I won the scoring and field-goal percentage championships, I thought I should have been the MVP. We had won 21 games in Buffalo my rookie year and 42 the second year. I thought that was a pretty dramatic improvement, and I felt I had done a lot to cause it. But Abdul-Jabbar got the MVP with me finishing second.”

Honors should continue to come Bob’s way the next few years. And he actually has received more accolades than most players ever can aspire to, starting in 1971 with a first-team berth on the junior college All-America team at Vincennes. That year, the Vincennes Trailblazers were eliminated in the regional tournament and had no chance to defend its national title, but, as a sophomore, Mac averaged 25 points and 15.7 rebounds for the Trailblazers.

Many four-year college wooed him following his departure from the junior college ranks. But he elected to return to his home state and attend North Carolina. “My parents hadn’t seen me play in two years,” he says, “and I thought they’d enjoy seeing me play pretty close to home.”

His one year with the Tar Heels, during which he averaged 19.5 points and 10.1 rebounds on a well-balanced club that lost only five of 31 contests, McAdoo was a consensus All-American. That was enough to convince Mac and the pro scouts that Big Bob belonged in the pay-for-play ranks right then. He applied for the NBA’s “hardship” status and was chosen as the second pick in the draft by the Braves.

He captured the NBA’s Rookie of the Year award during the 1972-73 campaign. Despite this high honor, Bob’s drive to succeed perhaps won’t let him rest until he clearly proves he’s the best player in the sport.

Mac’s intensity has astounded even experienced observers of the cage scene. “He was the most-intense rookie I’ve ever seen,” recalls one basketball career man who has been with four clubs in both major leagues in an administrative capacity.

McAdoo wasn’t an immediate starter with Buffalo as a rookie. The Braves had a seven-foot center, Elmore Smith, and Mac was asked to make himself a forward. “I wasn’t at all suited to playing against forwards on defense,” he recalls. “Guys like Lou Hudson and John Havlicek and Bill Bradley drove me crazy. And it was frustrating that I didn’t get to start right away, like I felt I should. I know I got the Rookie of the Year award, but I felt I could have done more with more playing time at my natural position of center.”

During the offseason between his freshman and sophomore NBA seasons, McAdoo received a great break—and so did the Buffalo Braves. The team dealt Elmore Smith to the Los Angeles Lakers for Jim McMillian, a tough “small” forward. McMillian has worked wonderfully into the Braves’ style of play, and Smith was traded to Milwaukee this past summer in the exchange which sent Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to the Lakers.

“I shudder to think what it would be like if I still were playing forward,” says Bob. Instead, his opponents now shudder whenever he launches one of his patented 18-foot jump shots.

At 215 pounds, McAdoo is considered relatively puny for a center. But he doesn’t worry. “I like playing the tall guys,” he smiles. “I played against Tom Burleson in college when he was at North Carolina State. The big guys always let me go outside and shoot. They just don’t expect me to shoot that much and that well from out there. Oh sure, they’re figuring it out now, but they hurt their team by trying to come out and cover me. They have to stay under the boards.”

McAdoo has also become proficient on defense. “Bob still has a tendency to be a little bit impatient on defense,” says Buffalo coach Jack Ramsay. “He used to try to block every shot that the other team tried. One of his big improvements has been learning to pick and choose when to try for the block, so that the other team is kept off balance. He’s also learned when to front a man and when to play him from behind. His quick reactions make him a much-better defensive player than many people thought he would be.”

Walt Frazier of the New York Knicks came away from one McAdoo defensive maneuver last season shaking his head. “It’s bad enough that he shoots like Cazzie Russell,” said Frazier. “But does he also have to play defense like Bill Russell?”

Despite a naturally quiet and reserved personality, Mac has become a very popular figure among his teammates in Buffalo and the growing legions of cage fans in western New York. Bob’s wife Brenda, whom he met at North Carolina, wishes her husband could relax more.

“But he’s a wonderful family man,” she allows. “We have a little son, Robert III, and the two of them get along great. Bob also likes our Afghan dogs and modern music, but most of the time, whether it’s winter or summer, he thinks about basketball.

The McAdoos return to Greensboro during the summer, and Bob works out at a local “Y” almost every day. He’s not satisfied yet with his progress through three seasons in the NBA, and despite the fact that he has scaled tremendous heights, all before the age of 24. “I want to become the best,” he says determinedly. “You can’t do that unless you’re willing to pay the price. This is my profession, my career. Other guys try to be the best they can at their type of work. I want to be the best in mine.”

It’s likely that McAdoo will achieve the goals he’s set for himself. He hasn’t missed many shots, and now he doesn’t want to misfire on the rest of his life.