[Here’s an interview with Celtic great Bob Cousy published in the “special” 1961 basketball issue of the magazine Sports Review. (On the cover is Adolph Rupp standing with his Kentucky Wildcats, still all-white.) Interviewing Cousy is Herb Bursky, clearly a big fan whose day job is with the Institute of International Education in New York. There, Bursky was involved with running the Fulbright scholarship program. That may explain Bursky’s early literary reference to Alexandre Dumas and the musketeer Charles de Batz de Castelmore, a.k.a., Count D’Artagnan. Everything else is all shamrocks and Celtics and, 60 years later, still counts as a good read.]

****

It was late afternoon on a mid-September day in New York as I walked west on Forty-second Street to keep an appointment with Bob Cousy, the brilliant backcourt star of the NBA champion Boston Celtics. As I moved along, a picture of the nimble, graceful Cousy flashed across my mind, and I thought of the dozens of times I had seen him rise to the occasion with a remarkable pass, a timely basket, or a wondrous ballhandling demonstration in the closing minutes of a tense game.

And, interestingly enough, I also thought of D’Artagnan, the bold-and-dashing French-blooded swordsman of Alexandre Dumas’ 19th century romantic novels. To me, Bob Cousy has always represented a modern-day reincarnation of D’Artagnan. The agility, daring and artistic Gallic touch of D’Artagnan seem to flow in every fiber of Cousy’s veins.

With a few minutes to spare before meeting Bob, I stopped off in a telephone booth and called Joe Lapchick, coach of St. John’s University. Lapchick, a member of the renowned Original Celtics and a successful coach in both college and the professional ranks, is one of basketball’s outstanding figures. He was, I thought, a good man to consult.

“How great a player is Cousy?” I asked.

“Cousy” said Lapchick, “is second to none. He is the number one backcourtman of all time. When the fans argue who is the top player in the game today, they bring up Cousy, Bob Pettit, Elgin Baylor, and a few others. The other guys are all big men. Cousy is a little man—6-foot-1. It is a tribute to his ability that he is mentioned in the same breath with the giants when they talk about the best player in the game.

“The charge that he is a showman, not a basketball player, is ridiculous,” Lapchick continued. “I’ve never seen Cousy do a phony thing in a game. Showmanship is a talent for doing something that holds up the game. Everything Cousy does has a purpose and is part of his enormous skill. I’ve been in this game since 1912, and Cousy would have been a great star in any era in the last 50 years. He’s a superstar and a helluva guy, as well.”

I smiled after concluding my conversation with Lapchick. Joe is honest and fair-minded and not given to exaggerated statements of praise. But he could not contain his enthusiasm in discussing Cousy.

Bob was participating in a press show as a public relations representative for a sportswear outfit when I met him. He stood in a corner of the room, sipping a drink, signing occasional autographs, and chatting easily with businessmen who were eager to make his acquaintance. His manner was friendly and approachable.

After 15 minutes, Bob indicated to me that he would be able to leave soon. “It won’t be much longer,” he explained. As we made our departure, a photographer briefly held up pedestrian traffic on the sidewalk and snapped a picture of Cousy. “Jeez,” said a small boy who witnessed the scene. “That’s Bob Cousy!”

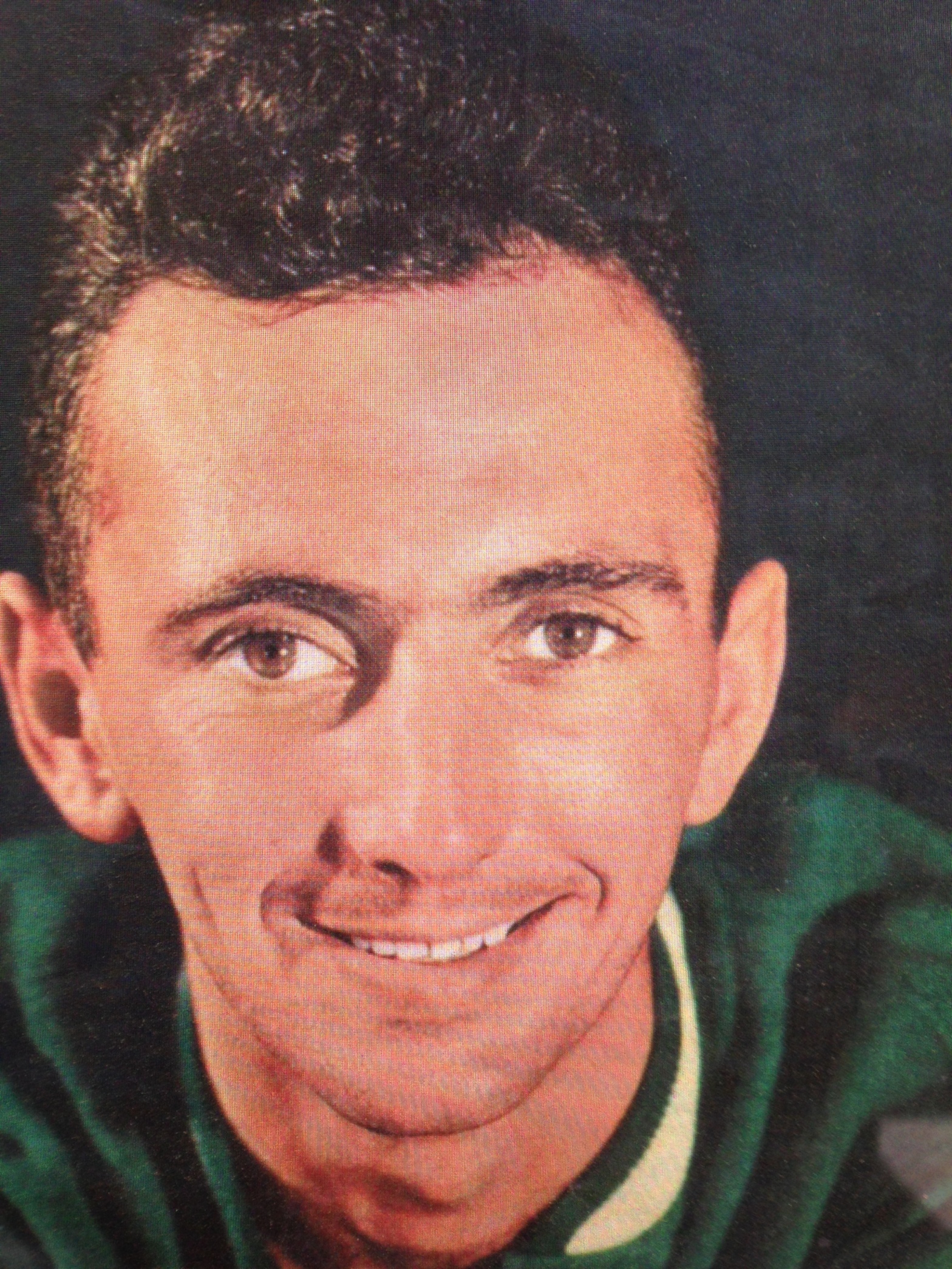

Moments later, Bob and I were seated in one of Cousy’s favorite stopping-off places in New York, a small, dimly-lit night spot off Times Square. Cousy was tanned from a summer at his boys’ camp in Pittsfield, New Hampshire. He looked trim and slender, and there did not appear to be an extra pound on his supple 175-pound frame. His facial expression was alert and intelligent, blending smoothly with his dark hair and dark eyes.

“Bob,” I said, “the fans love to watch the Celtics play basketball. Many people think they rate as the finest team ever to play the game, but others insist that the Minneapolis Lakers of the early 1950s were a better club. How do you feel about it?”

“Our club would have the edge,” he replied without hesitation. “We would have too much speed and depth for the Lakers. They had a strong team, but it was a five-man club—Mikan, Pollard, Mikkelsen, and Martin, with Bob Harrison and later Frank Saul as the fifth man. Our club has the bench strength to outlast them. We would run with them and try to get them to play our game. They would hold their own on the defensive board, but we would give them a real-battle underneath. Bill Russell would outshine Mikan, and Tommy Heinsohn would be in there, too. Heinsohn is as good a cornerman as I’ve seen since I’ve been in the league.”

“Talking about rebounding,” I said. “I was checking through the NBA Guide the other night and noted that you have excellent rebounding totals for a backcourtman. It isn’t widely known, but your figures in this department are impressive.”

“I’m not really a good rebounder,” Cousy answered. “There is a reason why my rebound totals were high six and seven years ago. At that time, before Russell came to our club, Ed Macauley was our big man. We had a different system in those days. The three frontmen would box-out underneath, and the guards would come in and rebound. Once we got Russell, my rebounding marks dipped down.”

(The records bear Cousy out. From 1950 through 1956, his rebounding totals exceeded 400 five times. With the advent of Russell, he dropped to more conventional totals for a small man.)

“Over the years,” I remarked, “every club in the NBA has tried to figure out a way to harass you. Who have been the best defensive men you’ve been up against?”

“Slater Martin comes first,” Bob said. “He has terrific powers of concentration, and he never lets up. Then I would pick Larry Costello of Syracuse and Gene Shue of Detroit, and one other man . . .” Cousy paused for a moment, thinking back across the seasons. “Yes, I remember . . . Walther . . . Paul Walther, who played for three or four clubs in the league.“

“There is one man you haven’t named,” I said, “but I recall a brief incident in which you paid tribute to him. I mean Johnny McCarthy of St. Louis. I thought Johnny did a top-flight job of playing you in the championship series last spring. After the Celtics won the last game, most of the Boston players were jumping around, as players usually do in a moment of victory, but I noticed that you slipped through the crowd and shook McCarthy’s hand.”

“Yes,” Bob agreed. “John did a helluva job. He concentrated so much on me that he sacrificed himself. He didn’t get much recognition for it, either, and I went over to the St. Louis writers after the final game and told them about McCarthy.”

Cousy spoke crisply. His answers were clear, direct, and to the point.

“When you’re on defense,” I asked, “who gives you the most trouble to guard?”

“A small man like Larry Costello gives me more trouble than a big man,” Cousy replied. “This isn’t widely known, but I prefer to guard a big man rather than a small man. A little guy is fast and agile and has quicker reactions than a big man. Consequently, he’s harder to play.

“It’s true that a big man like Richie Guerin (6-foot-4) will take me inside and get his 20 or 30 points, but there is a fallacy in that system. When Guerin takes me in, the big men on his club are playing in unnatural positions. There were games last year in which Charlie Tyra (Knick center) didn’t get off many good shots against us. I don’t mind it when a big man takes me in. I figure it may hurt his club in the long run with his pivotman playing out of position.”

“There are times when you take a man inside, too,” I pointed out, thinking of a game in 1958 when Cousy took a New York rookie inside and outmaneuvered him.

“True,” he admitted.

I swung the subject over to the other members of Boston’s star-studded team. “How much does Frank Ramsey mean to the Celtics?”

“He means a good deal,” Bob answered. “Ramsey plays either position—forward or guard. He’s a hustler, and he scores the clutch basket.”

“How about Bill Sharman?”

“Bill’s tough. He’s strong, a good defensive player, and a great shooter.”

“Here’s a question that always comes up when the fans talk basketball. How would you compare Russell and Wilt Chamberlain?”

Cousy smiled. “Starting from scratch,” he said, “I would take Chamberlain, but Russell is the better man for our club. He fits in with our personnel. He runs with us, passes on the run, plays tough defense, and plays team ball.”

“When Chamberlain came along,” I asked, “did this provide Russell with an added stimulus to do better?”

Bob nodded. “Chamberlain made Russell a better player,” he said.

“You’ve been in hundreds of close, hard-fought games. Which club has given you the toughest time over the years?”

“The old Rochester Royals of the early 1950s always gave us hard games,” Cousy said. “That was the team with Bob Davies, Bob Wanzer, and that group. St. Louis has been our strongest opponent in recent years.”

“This is a tough question to ask,” I declared, “but I think it’s a logical one. Your style of play exposes you to criticism. You’re a flashy ballhandler and dribbler, this gives rise to guys in the stands who yell ‘showboat’ and things like that. What is your reaction to this?”

Cousy listened carefully as I phrased the question. “I’ve acclimated myself to the situation,” he replied. “I got rid of rabbit ears a long time ago. Usually, I don’t hear people yelling at me during a game, but it produces a helpful reaction if I hear it. I’m a stubborn guy, and this sort of thing inspires me. The more inspired I get, the better I play.

“Actually,” he continued, “I don’t use the behind-the-back pass as often as people think I do. When I use it, I have a good reason for it. When a situation develops where I can help the club with a certain maneuver, I go ahead with it.”

As Cousy spoke, I thought of the excited crowds in the lobby of Madison Square Garden on a night when the Celtics are in town. There is an air of expectancy, in anticipation that something special is about to happen, and the name of Bob Cousy seems to be on everyone’s lips. Even the fans who complain of his ballhandling tactics seem to be harboring a kind of affection for him.

“You’ve brought color to the game, Bob,” I commented. “You brought people into the arenas around the country, and you’ve helped to build pro basketball.”

“The game does need color,” he said.

“How much better is the league today than it was 10 years ago when you broke in with the Celtics?”

“A much-better league. Everything is accelerated, particularly the shooting. These kids can really shoot.”

“How do you feel about the charge that the NBA doesn’t play good defense?”

“I disagree,” Cousy responded. “The guys in our league play strong defense, but you can’t sustain it over a long schedule. There is a human factor involved. Some nights, defense will be very good. Other nights, you might be involved in a runaway-type game, and the defense is lax. Last year, our club won 16 straight, and we went into St. Louis to try for our 17th. St. Louis is tough on their homecourt, but we busted our fannies that night and held them to 82 points to extend our streak. Put it this way—the guy who says NBA defense is lax all the time is just as wrong as the guy who says we play top-flight defense every night of the week.”

We talked about Cousy’s high school and college days, and Bob grinned when I mentioned that he had been cut from the basketball squad as a high school underclassman. “I didn’t even make the jayvees that first year,” he acknowledged.

I remarked that Cousy was a New York boy, born and bred in the great metropolis, but his college (Holy Cross) and professional career had been devoted exclusively to the Boston area. He had become a New England sports idol, comparable to Ted Williams of the Red Sox.

“Home is where your friends are,” he said. “I made business connections while attending Holy Cross, and Boston and Worcester are home to me.”

“How about coaching?”

“I haven’t given it much thought,” he said, “but if I do coach, it will be for the enjoyment of it, not as a livelihood. When my playing days are over (he is now 32), I plan to stick with my public relations work, my insurance agency, and my boys’ camp.”

After a while, we shook hands, and I wished Cousy continued good fortune.

“When you get to be my age,” he smiled, “you need it.”

I walked over to Broadway, and the image of Cousy in action again came to mind. I saw him crisscrossing up the floor, bluffing a pass to Sharman, and then driving in for a neatly-executed layup shot. I heard the sound of applause, the hoarse shouts of men, the shrill cries of women, and the whistles of exuberant boys. Few men have the magnetic ability and personality to lift an audience to heights of great emotion and to bring vitality and excitement into the lives of the onlookers. Bob Cousy is one of those men.