[Modern journalism resides on several ethical pillars, including being factual and being objective. But journalists aren’t robots, and sometimes they profile people with whom, for whatever the reason, they just don’t connect, and their objectivity wanes by the end of the assignment. This profile of the young Earl Monroe, published in the magazine True’s Basketball Yearbook, is a case in point.

Journalist John Devaney has been assigned by his editor to get up-close-and-personal with Monroe, the league’s premier young showman. But Earl the Pearl won’t open up to him. He’s muttering one-word answers, and Devaney is stuck with a subject who, as they say in business, is “a bad interview,” and that doesn’t auger well at the typewriter. Devaney can’t help taking out some of his frustration on Monroe, describing him as being “as alive as a soaked sponge.” (Equally frustrated Baltimore reporters referred to “The Pearl” behind his back as “The Clam.”) Despite the bad interview and some journalistic moping, Devaney’s profile still offers a nuanced look at an NBA legend as a young man trying to wend his way through the world of pro basketball as a showman with all the glitter of a pearl.]

****

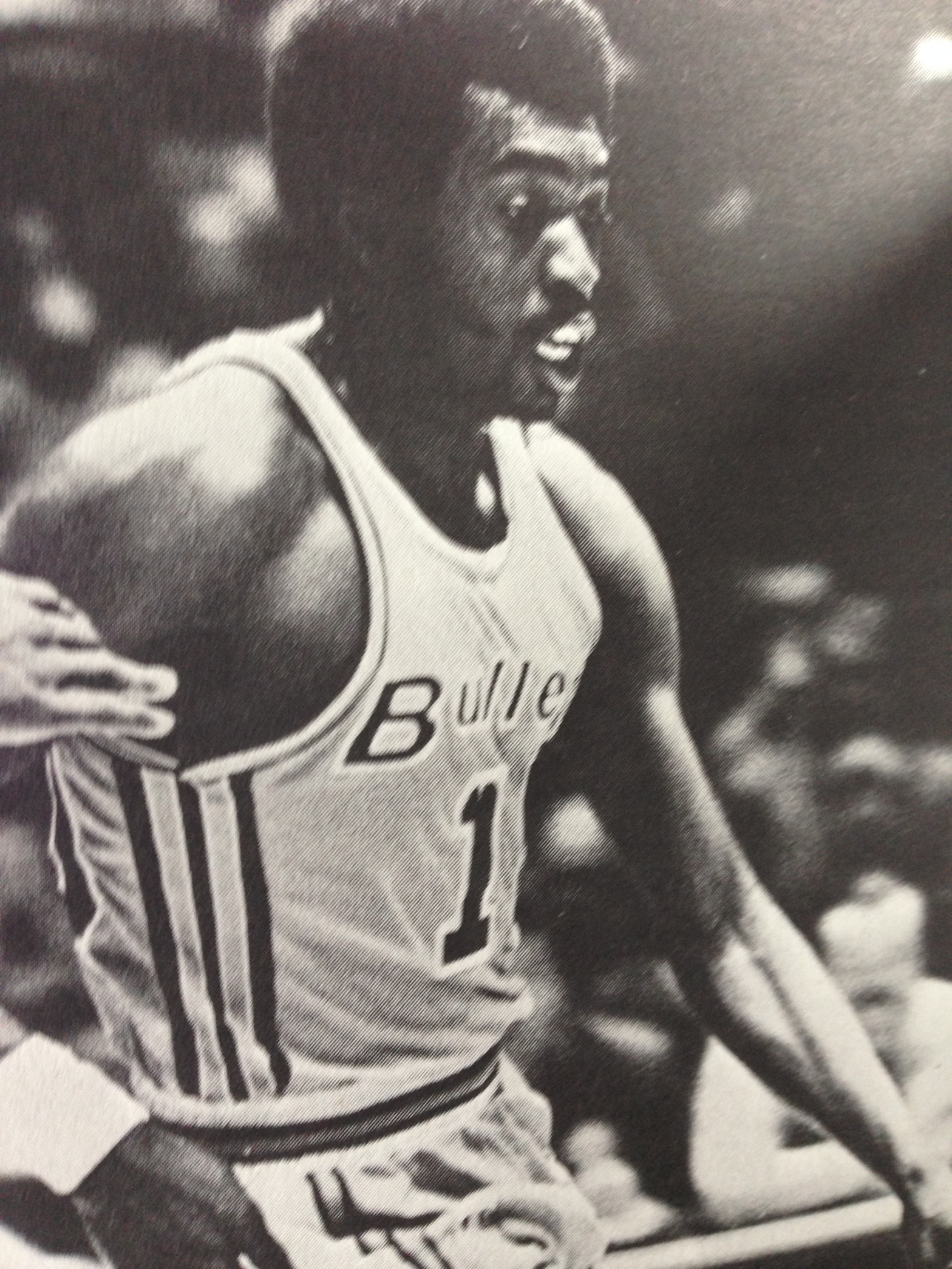

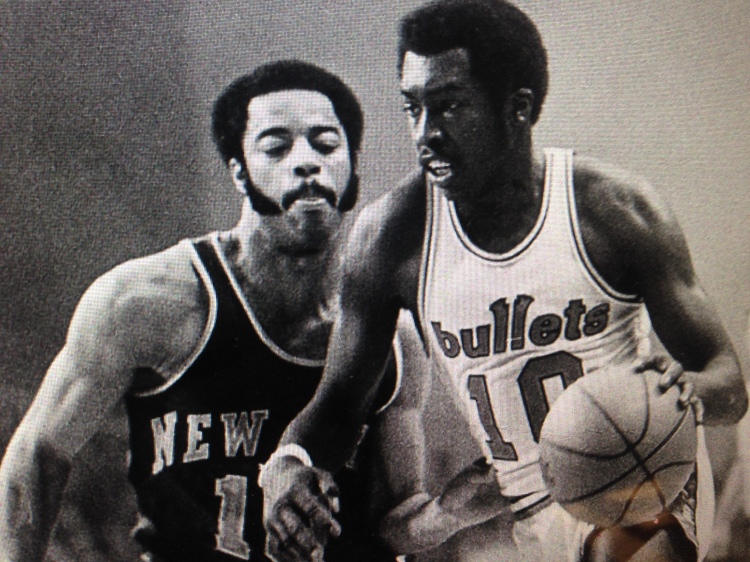

Earl Monroe dribbled the ball upcourt for the Bullets, the Knicks’ tenacious guard, Walt Frazier, up tight on him, the two as close as a boxer and his shadow. At the foul circle, with a quick thrust of his right hand, Monroe blurred the ball behind his back, dribbled it between his legs, faked once and twice and a third time. Then—with Frazier faked halfway to the sideline—Monroe jumped high into the air. He cradled the ball on the tips of his fingers, then spun it on a high and lazy arc toward the basket.

Swish! The nets danced. Two points for Earl the Pearl, and some 8,000 people in Baltimore’s Civic Center—a good half of whom had come to see Earl—shook the air with a sudden roar. “Earl the Pearl,” yelled someone high up in the seats. “Earl, Earl, best in the world!”

Perhaps one day 6-foot-3 Earl Monroe just may be the best backcourtman in the world. Last season—only a rookie—he led the Bullets in total points, game average, field goals, free throws, and assists. He averaged 24.3 points, fourth best in the NBA. No one was surprised when the NBA players picked Earl as Rookie of the Year; the victory was by a landslide, with 116 votes for Earl and six for second-place Bob Rule of Seattle.

In one year, Earl the Pearl had proven himself as a playmaker, passer, and shooter. “No one since Oscar Robertson,” wrote one reporter, “has done so well in his rookie season.” Many people, in fact, were reminded of the Big O as they watched Earl penetrate defenses, pass off with slickness to a free man, or work himself in close to the basket with artful dribbling.

“With all the things he can do on a basketball court,” said Baltimore coach Gene Shue, “Earl Monroe makes Bob Cousy look like a little boy. That’s not a knock at Cousy—it’s just that Monroe is a great talent.”

But if Earl Monroe is a pearl on a basketball court, he is a bit of a puzzle off it. Grasping a balloon with boxing gloves, wrote reporter Bob Rubin, would be an easier task than explaining the contradictions in the makeup of Earl the Pearl.

There is, to begin with, the relationship of Earl the Pearl to his fans. It is a natural, spontaneous thing: people yell and scream or murmur admiration when Earl runs downcourt without the ball. When Earl played at Winston-Salem State College, he became famous as Earl the Pearl because his fans chanted, “Earl, Earl, Earl, the Pearl! Earl, Earl, best in the world!” Fame stuck with him when he arrived to play for the Bullets. Last season, some 5,000 people came to see the rookie play his first game—not a regular-season game, not even a preseason exhibition game, but a preseason intra-squad game, of all things.

Earl the Pearl. Like another nickname, Wilt the Stilt, it can help to make its owner famous—and very rich. Earl hates the name. “I don’t like that name,” he says. “I never said I did. I never encouraged people to call me that. But there’s nothing I can do to stop them.”

Apart from discouraging people from calling him a nickname that can only help him, Earl discourages fans from making him any kind of idol. After a game, he is polite to adoring fans, but usually he signs one or two autographs, then thread-needles his way through the big crowds like a runaway snake, refusing to sign any more autographs. “I hate signing autographs,” he says. “It’s the only thing I dislike about basketball. I really love this game. But what I hate is the crowds afterwards, and the people wanting to shake your hands, the people who want you to make speeches.”

During last season, the Bullet front office pleaded with Earl to make personal appearances. This is a franchise that has played before pitifully thin crowds, one reason being that apart from Gus Johnson, who has often been injured, the Bullets have lacked a star. There are two big voids on the Baltimore sporting scene: 1) a winning-and-popular basketball team; 2) a winning-and-popular basketball star.

Earl the Pearl can be that star, and he can be the playmaker and scorer to make the Bullets that winning team. “I will do whatever I can to help this team win games,” says Earl. “But I don’t like to go out and make appearances and talk to people. That isn’t my style.”

All right, so that isn’t his style. He’s the quiet, shy type. “He’s just a kid who loves to play basketball,” says a teammate, Bob Ferry. “You can tell it every time he walks on the floor. He enjoys playing the game even more than people enjoy watching him play.”

But how do you explain this? This summer, Earl toured much of the nation, visiting low-income Black urban neighborhoods as part of a program set up by Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Earl talked—yes, talked—to Black kids in schoolyards. He made speeches on how to play basketball and on why it’s so important for youngsters to stay in school. And when he had finished talking, he signed autographs. Lots of autographs.

Contradictions. Contradictions piled on contradictions. On the court, he is so flamboyant and daring with his passes and his behind-the-back dribbling. Off the court, it is almost as though he had clicked off a switch inside himself; all the vibrancy is gone, and he is as alive as a soaked sponge. Talk to him, and you get these kinds of answers: “Yes.” “No.” “Maybe.”

“I just don’t talk a lot,” he says.

When he does talk, he reveals other contradictions. For example, he talks about his four years at Winston-Salem State with nostalgia and warmth in his voice. “Those were the greatest years of my life,” he says. Yet, as he tells you later, he quarreled with his coach when he first arrived, though later they became close friends. And he encountered several instances of racial bias in restaurants around that North Carolina city.

One of Earl the Puzzle’s contradictory statements got him into much-publicized trouble last season. In a close game against the Knicks, Earl—usually impeccable from the free-throw line—missed two foul shots that would have tied the game, and New York won by two points.

After the game, a glum Monroe slumped on the bench in the clubhouse. A reporter asked him if he was eligible for Army service. Normally, Earl would have said “yes” or “no” and fallen silent, waiting for the next question. Instead, he apparently muttered something about not going into the service, if he were called.

The next day, black headlines broadcast the news: Earl the Pearl was another Cassius Clay. An embarrassed Earl said the whole thing had been a misunderstanding. When reporters persisted with questions, Earl smiled and said, “I think too much has been said about that already.”

He did nothing, typically, to clear up the puzzle: Would he, or wouldn’t he, go? Eventually, Army doctors found that Earl’s knees were arthritic, and he was declared 4-F [unfit for military service]. But Earl had left behind him a wake of confusion and curiosity.

Some of the curiosity concerned Earl’s views on civil rights. Was he, like Cassius Clay, a Black Muslim, who opposed military service? Earl made it very clear that he was not a Muslim. He is a supporter of action for civil rights, but you won’t find The Pearl—in his handsome blazers—walking down the street carrying placards or shouting slogans.

“I do what I can for Black equality,” he says. “I have my own ways of supporting those causes—giving speeches to kids, contributing money—but I’m not the type to lead marches on City Hall. That’s not my thing.”

But whatever confusions he causes off a court, The Pearl confuses only his opponents on the court. His teammates are amazed by him. After one game, fellow backcourtman Kevin Loughery studied the statistics. “He hardly looked like he was working out there,” said Loughery, “and he still came up with 30 points. You know he’s got to be tired—we all are—after this stretch of games (10 in 12 days). But he goes out there and gets 30 without even trying to score.”

Another teammate, Ray Scott, grew up in the same Philadelphia neighborhood with Earl. “Back home, we’ve always known Earl had it,” says Scott. “I’ve only seen one other rookie come into the league like Earl—where you can just tell. That was Dave Bing, when I was at Detroit last year. Earl’s got it up here.” Scott tapped his head.

Scott then explained, “He didn’t score a lot in the exhibition because he was trying to work with us up front, get us accustomed to his moves. That’s a smart rookie. He’ll be a great one. Listen, Dave’s got heart, but Earl is just beautiful. That’s why they call him The Pearl. He is The Pearl; he is beautiful.”

During his days at Philadelphia’s John Bartrum High School, Earl would not have impressed any college dean of admissions with his grades. “I just didn’t like studying books,” he says. “I just didn’t care to study.

His flair for putting a round ball through a little hole impressed college scouts, but Earl’s grades were not good enough to get him into a lot of schools. For a few months, he attended Temple Prep, hoping to improve his high school scores to a point where he could attend Philadelphia’s Temple University. This assault on the textbooks did not succeed; Earl left school and got a job as a $60-a-week shipping clerk.

“That’s kind of a dark spot in my life, that period,” he says now. He does not like to talk about those days. He remembers having to get up at seven o’clock in the morning, every morning, a memory that still makes him shudder. Today, it’s a rare day when Earl arises before noon.

Working with Earl was a good friend, Steve Smith, also a crack high school ballplayer. One day a recruiter came by from Winston-Salem to talk to Earl and Steve. If he studied hard, said the recruiter, Earl could make passing grades.

Earl looked around the grimy office in which he hefted heavy packages, grunting and sweating. “I knew that I could do something better than working as a shipping clerk,” Earl says now. “And I knew that the only way to get anywhere was if I went to college and studied harder than I’d been doing in high school.” At one o’clock one afternoon, he and Smith quit their jobs and took a bus to Winston-Salem.

By his junior year, Earl was averaging 29 points a game and hitting 56 percent of his shots. In his senior year, co-captain of the team with Smith, Earl was averaging 41 points a game, tops in the nation, while hitting an astounding 70 percent of his shots. In one game, he scored 68, in another 58.

His antics with the ball were almost as exciting as his scoring. He won one game by dribbling the ball two minutes to kill the clock. He dribbled the ball behind his back, under his legs, close to the floor. His dribbling helped him press closer to the basket to make those short, Big O kind of shots that coaches love, the ones that are likely to go in while drawing a foul.

In Earl’s senior year, a reporter wrote: ‘There are three major attractions in college basketball today—Lew Alcindor of UCLA, Westley Unseld of Louisville, and Earl Monroe of Winston-Salem.”

Gene Shue and the Bullets didn’t agree. They wanted to draft Providence’s Jimmy Walker. But in a coin-toss with the Detroit Pistons, the Bullets lost Walker to the Pistons and instead had to settle for their No. 2 choice, Earl the Pearl.

(It is interesting how so many of these coin-tosses work out. The Boston Celtics lost a coin-toss and had to settle for Bob Cousy instead of Max Zaslosky. The Detroit Pistons lost a coin-toss and had to take Dave Bing instead of Cazzie Russell.)

After seeing Earl perform against his veterans, Shue was mightily impressed by The Pearl’s passing ability. But Earl wasn’t scoring. In the first month of the season, Earl was making the mistakes so common among rookies: He was looking for the free man too often instead of taking the good shot for two points.

One day, Shue took his rookie aside. “Go out and play as you did in college,” said the coach. “You’re an offensive player.”

Quickly, The Pearl showed just how offensive-minded he could be. In a game against the Lakers, he flipped in 56 points, a Bullet record, hitting on 20 of 33 shots while scoring 37 of his points in the second half. Shortly after midseason, Earl joined the NBA’s top scorers. And while scoring 30 points a game more often than not (in 11 of 12 games during one stretch), he pushed up his average from around 14 points a game to 24 a game.

He didn’t forget how to pass. “Earl Monroe,” said Shue near the season’s end, “can make every pass that has to be made. He has a flair for showmanship, which is great, but basically, he is a very sound basketball player. He does the things you want a guard to do in pro ball.

“If you are going to run—and you have to, if you are going to win—then the ball has to be advanced as quickly as possible. Whether he’s passing or dribbling, Earl gets the ball into the offensive zone as fast as anybody in the game. He penetrates defenses, and that’s something we didn’t do before.”

Characteristically, the Pearl can be ambiguous and confusing about his flashy passing and dribbling. “I don’t try to be a showman,” he says. “I’m not trying to get any attention; I’m not trying to be a Globetrotter out there. The way I play is just my style. When I do something on the floor, it’s because that’s the way I think I can get the job done.”

But then, without hardly taking a deep breath, Earl indicates that he is aware of the value of being a showman who gets attention. “I think that pro basketball needs players who can excite the fans,” he says in his soft-spoken way. “If I can get their attention and cause excitement, it’s got to help me.”

Earl the Pearl will always get attention. What he has got to do, of course, is to stop getting attention for the wrong reasons—like being misunderstood.