[Here’s a mostly slice-of-life profile of Lou Hudson, chronicling his early years with the St. Louis/Atlanta Hawks. Otherwise known as, pre-Pete Maravich. The text comes from writer Paul Hemphill, then with the Atlanta Journal, and he wrote the article for the March 1970 issue of SPORT Magazine. Enjoy!]

****

The apartment, like the personality of the man, paying the rent, was in a suspended state of development: tentative, promising, on the verge of crystallizing, yet still vague and lacking a character of its own. They are nice apartments, all right, 10 miles northeast of Atlanta where the Swinging Singles congregate, modern apartments with a Scandinavian name, and a huge A-frame clubhouse and a cloverleaf pool, and bright green swatches of coarse grass. But he had moved into his just as the National Basketball Association season was opening and simply had not found the time to look after domestic chores. The table-model stereo squatted on the carpet like a stunned frog. Scores of well-worn albums, ranging from acid rock to Country Charley Pride, leaned against the bare white wall. Packing boxes served as tables. Indeed, the only real furniture in the place was a sofa and a bed loaned to him until the new stuff he had bought came in. “It’ll be my luck,” Lou Hudson was saying, “to be off on the road somewhere when they ship it.”

“What you need is a wife,” he was told.

“Yeah. Uh-huh.”

“Wives take care of things like that.”

“Sure.”

“No prospects, then.”

“I just haven’t found the one that can turn me on,” he said, knowing it was trite, leaving the conversation for a few seconds, drifting into his own thoughts. “Well, it’s more than that, really. See, I’m going through a mental transition right now. I’m trying to get my mind together, and right now I don’t think I could handle marriage. If I found a woman who didn’t have her mind put together, I’d have more problems. You know? I mean, like, most people go through life with a lot of hangups, and I’m trying to decide what I want to believe in. I’m just not complete. I don’t know what I am yet.”

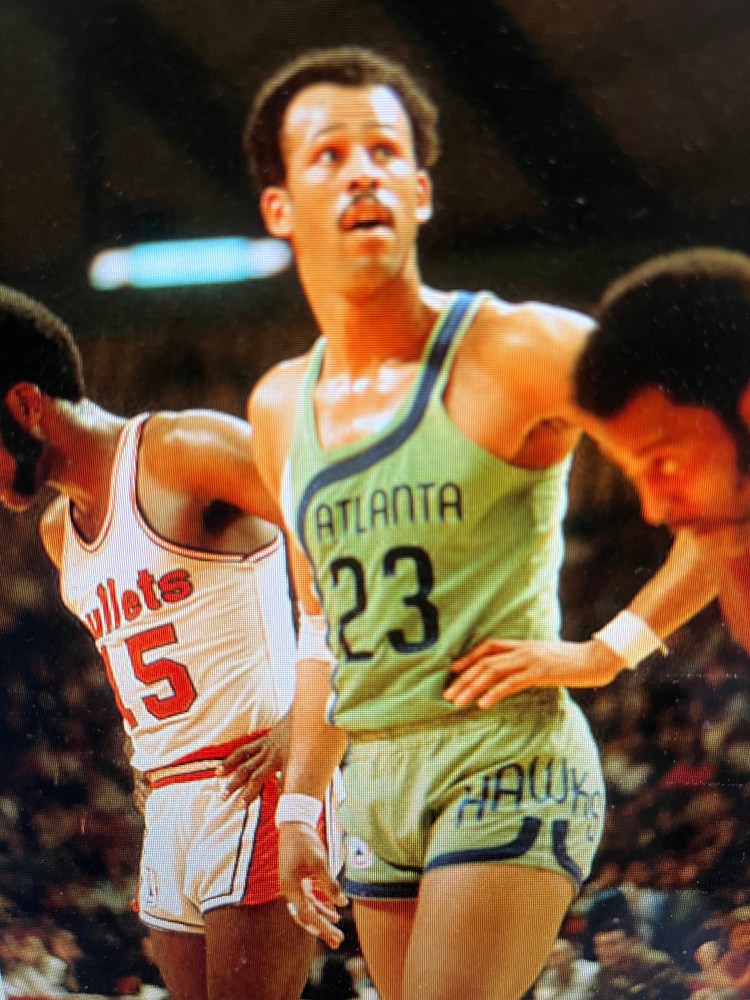

Hudson was talking about himself as a man, of course, not as a basketball player. “That stuff about being in ‘transition’ doesn’t relate that much to the court,” he says. But it really does. Now his fourth year in the NBA, Hudson seems to be in transit, heading towards star billing with the Atlanta Hawks. In a sense, this is the coming-out season for Lou Hudson. Up to now, there have always been obstacles in his way. In his senior year at Minnesota, Lou had to play the last half of the season with a cast on the wrist of is shooting arm. Then came his first year in the NBA, and although he barely missed making rookie of the year, he had the usual problems of acclimating himself to the pros. Next came Army duty, which caused him to miss the first half of his sophomore NBA season, and last year he was held up in his development when coach Richie Guerin decided to move him from forward to guard. So, the 1969-70 season has to be Lou Hudson’s year. So far, so good.

At one point early in this season, Hudson’s field goal percentage was 54.0, placing him second in the league, the nearest guard lagging behind at seventh. By the time the Hawks had played 33 games, Lou was averaging 25.6 ppg. and hitting 52.9 percent from the field, placing him sixth in the NBA in both categories.

“Lou’s still got some things to learn at guard,” says Guerin. “He doesn’t handle the ball well enough all of the time, and he has trouble playing it like a guard on defense. But he’s going to stay at guard, and when he hits his peak, he’s going to really be something. As long as he’s got that jumper, he’s hell.”

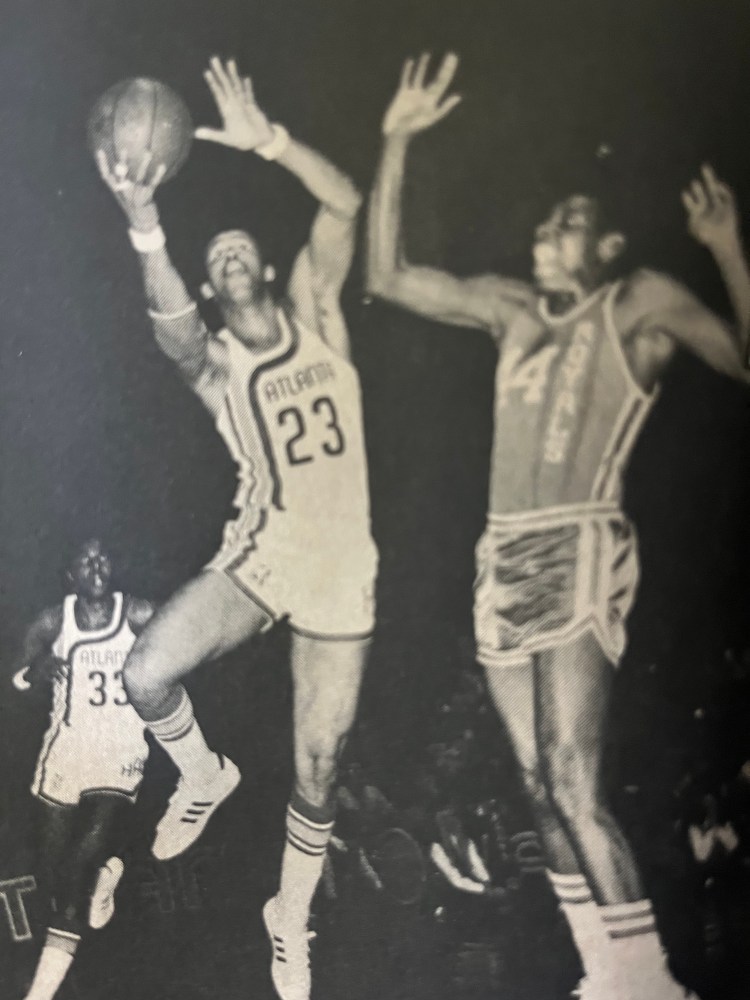

The jump shot, as soft and precise as Hudson’s muted drawl, is his thing. He has unusual spring in his legs for a big (220) man, and this, coupled with his height advantage over most other guards (he stands 6-feet-5), usually leaves him hanging in the air, unmolested, when he stops and springs and fires (at which point the adoring Atlanta fans let out a collective gasp that sounds like “Loooouuuuuu!!!”). All but 70 of the first 631 shots he had taken from the floor this season were jumpers, usually from 12 to 15 feet out—and he had hit slightly more than half of them. Indeed, when Hudson scored 57 points against Chicago to tie Bob Pettit’s all-time Hawk single-game scoring record, only two of the 34 shots he took were layups.

At age 25, Lou Hudson (or Sweet Lou, or Super Lou, as the fans call him) is handsome and articulate and unflappable (“sort of a Belafonte of the backboards,” gushes one admirer), and is, in his time of transit, earning the respect of his peers. Bill Bridges, the Hawks’ captain and Hudson’s roommate on the road, calls Lou “the best ballplayer we have.” Walt Hazzard goes a step further. “Lou, in time, is going to be the best ballplayer in the league,” says Hazzard, who was the guard beside Jerry West for three years at Los Angeles. “Right now, Lou’s better than West, although Jerry’s getting old and has been injured a lot. If Lou and West ever got into a game of ‘horse,’ it’d be the damnedest ‘horse’ game you ever saw, and Lou would win.”

****

It looked like Hudson and West might play a game of horse one bitter cold day in mid-December 1969. It was 1 o’clock in the afternoon, and seven hours later, Hudson and the Hawks would go against West and the Lakers at Alexander Memorial Coliseum on the Georgia Tech campus (the Hawks still do not have a home of their own in Atlanta, although with ex-governor Carl Sanders and real-estate developer Thomas Cousins as co-owners, they ought not to have too much trouble finding one). The Hawks had flown back into town late the afternoon before from a tough trip to Cincinnati, Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, and San Diego (splitting it, 2-2), and Hudson had slept it off until almost noon.

When he awoke, he read about the possibility that West might not play (“JERRY WEST, Fatigued Laker,” explained the caption in the paper). Hudson didn’t believe it. Already, he had a mental picture of himself guarding Jerry West as he tooled his desert-tan Toronado out of the

parking lot and left the bleak apartment to run some errands downtown. He was quiet.

Lou Hudson, you learn very quickly, is always quiet. He does talk about girls (he and Jimmy Davis are the only bachelor Hawks) and the weather and basketball, but he doesn’t talk about himself or his thoughts unless he is run into a corner. This has brought about an almost ludicrous situation, where 10 of the people closest to him are likely to offer up 10 different descriptions of him.

“Lou is probably the most uncomplicated man I have ever known,” says Hawk publicist Tom McCollister. “No, no, no,” says Atlanta Journal basketball writer Frank Hyland, “it’s the ones who go around laughing, and slapping tails that are uncomplicated; Lou is complex, boiling inside.” Says a business associate (Lou is an officer in a quick-sandwich franchise operation): “The only color Lou sees is green.” Says yet another close observer of the Hawks: “He’s simply sitting on the fence, trying to decide who he thinks he is, and one of the big things bugging him is the racial thing; which way he ought to go on that.”

Hudson is, in short, a paradox. He never quite graduated in physical education at Minnesota, but was last seen reading a book on the plane that was written by a German and deals with organisms. He used to drive a flashy red car, but traded for the current beige one because the first was “too showy!” but now he has taken to growing a mustache and wearing mod clothes and ogling the girls on Peachtree Street, things he was never known to do even as the 1969-70 season began.

Indeed, one of the few things that has not changed lately about Lou Hudson is that he still goes back to Greensboro, North Carolina, as often as he can, to check up on his parents and his friends. “He calls me whenever he comes to town, and he’ll sort of amble in and sit down, and we’ll talk a while,” says Irwin Smallwood, the man who “discovered” Hudson. Smallwood, now a news executive with the Daily News, says about Hudson. “He’s a good man who looks out for his folks and stays in touch with his high school coach. His parents live in a five-room brick home in an integrated neighborhood, and they’re driving a yellow Buick convertible that used to be his. Summer before last, he worked in the city recreation program here, and after he got out of college, Greensboro honored him with a biracial dinner at one of the nice motels in town.”

Greensboro is a pleasant, progressive town of about 150,000 population now, with more than its share of Southern liberals and intellectuals. But it wasn’t, and still isn’t, all that pleasant for Blacks. The Hudson family—Lou has one younger sister and four sisters and a brother who are older—was making a living as best it could around 1960 when Lou was beginning to develop as a basketball player. Lou’s dad worked in a pajama factory, Mrs. Hudson was a domestic, and Lou shined shoes at the downtown newsstand.

Lou was fairly active in school affairs and was participating in all sports at Dudley High School. Dudley High was the state’s Black high school basketball team, and Louis Hudson was its rebounding and scoring leader, but in the limbo that was Black high school sports in those days, few people knew about him.

Enter Irwin Smallwood.

For about a dozen years, Mrs. Hudson had been working as a maid for Mr. and Mrs. Irwin Smallwood. Lou’s mother knew, of course, that Smallwood was executive sports editor for the Greensboro Daily News, and one day she told him her son was a good basketball player, and he ought to go see him play sometime. Eventually, Smallwood did go to watch a Dudley High game, and he couldn’t believe what he saw. “Louis would get the rebound, bring it down court, shoot, score, and go back for another rebound,” Smallwood recalls. “He scored 20 points in the first 16 minutes I saw him play. He reminded me of Tom Gola, Doug Moe, those guys who were the first of the smoothies.”

So impressed was Smallwood that he began to write about Louis Hudson of Dudley High School and started passing the word to college coaches in the area like Bones McKinney of Wake Forest. North Carolina, for one, talked to Hudson about taking an athletic scholarship and breaking the color line there, but Lou was a shy kid, who “wasn’t about to be an ice-breaker by myself in North Carolina back then, not with (Robert) Shelton (of the Klan) about 50 miles away.” Lines of communication had already been established between North Carolina and some of the Northern and Midwestern universities, resulting in a sort of underground railway system that placed many promising Black athletes from the state on Big Ten teams. From dozens of offers, Lou finally decided on Minnesota.

A major factor in his choice was the fact that North Carolinians like Bobby Bell and Carl Eller were already playing football at Minnesota, and when Lou signed on, he joined Archie Clark (now with the 76ers) and Don Yates to form a trio of the first major Black basketball players the school had had. As it turned out, the only real adjustment Lou had to make, as he went off to the strange land for school, was to the weather. “I went up there to check out the campus in the spring, and it was nice and green, about 40 degrees,” Hudson remembers. “That first winter, it got down to 35 below, and I started thinking about home.”

But the cold weather didn’t hamper his style. In his junior year, Hudson led the Big Ten in field goals and set a school single-season scoring record of 588 points for a 23.3 average. When he broke his wrist early in his senior season, he learned how to shoot wearing a cast (scoring 20 points and hitting 50 percent of his shots the first night out) and wound up with a 19.8 per game scoring average. When his playing time at Minnesota had run out, Lou had made All-America once, All-Big Ten three times, and fallen six points short of setting an all-time career scoring record there.

He was the first pick of the Hawks, who were then in St. Louis, the fourth draft choice selected in the NBA that year. And since basketball was his real passion, he was happy to join the Hawks.

They were happy to get him, too. In his rookie season, Hudson started 80 games, led the Hawks in scoring with an 18.4 average (averaging 22.6 in nine playoff games, when the Hawks lost out to the Warriors in the semis), was runner-up in the Rookie of the Year balloting and became an integral part of a “new” Hawk team. Pettit and Guerin were through as players and were being replaced by new names like Hudson and Bridges and Joe Caldwell. The next season, 1967-68, should have been a big one for Hudson, but it was wrecked from the start when he had to do five months with the Army and missed about half the season (still, he averaged 12.5 ppg. during the regular season and 21.7 in six playoff games). Last year, with the Army behind him, Hudson led the Hawks with a 21.9 scoring average (15th in the league), hit 49.2 percent from the field, made the All-Star team, and helped his team, now transferred to Atlanta, to its second-best season’s record ever (58-34).

But the high point of that season for Hudson—what can be called a pivotal point in his career— came when Guerin decided to permanently move Lou to guard. And the coach wasn’t very subtle about it. He baptized Hudson in fire by assigning him to guard Jerry West in the playoffs against the Lakers. Hudson responded magnificently. West hit only 34 percent of his shots and was held to 75 points in four games (his average had been 30-plus per game for the season), while Lou was scoring 92 points on 42 of 88 shots. “That did it,” says Guerin. “From then on, he was a starter at guard.”

****

And now, he was on his way to another meeting with West, a crucial meeting in a way for both teams, even though it was still early in the season. The Hawks were clinging to a three-game lead in the Western Division, but they had been playing unimpressive ball lately. The Lakers had lost three in a row and were struggling to make the playoffs. Hudson thought of all that, but first he had something else to get out of the way.

He tooled his Toronado into the backside of the downtown area, heading for the Black soul station WAOK to tape that night’s Lou Hudson Show. He was wearing a get-up that nobody back at Dudley High School would believe: mustard bellbottoms, blousy silk pale-green shirt, buckled boots, Nairobi striped vest, hunting jacket, and black corduroy engineer’s cap. He talked about how he felt he was an uncomplicated person. “I just don’t try to put my problems on other people. If I have problems, I feel that I have to solve them. Letting the world know I have problems isn’t going to add any comfort to me. The Auburn thing, now, that was different.”

This is probably where Lou Hudson’s “mental transition” is taking place, although it is only a part of the whole. In this era of the outspoke Black athlete, Lou Hudson, perhaps, because of his upbringing, has been a rarity. He has not been flashy, nor demanding, nor opinionated, nor in in the least bit verbal. But earlier this season, eight Black athletes complained to the Justice Department about treatment they received at a motel restaurant in Auburn, Alabama, before a Chicago-Atlanta game there, and one of the eight later interviewed by government investigators was Lou Hudson. “I was raised in the South and I’m used to that,” he says now, “but I haven’t been confronted with it lately, and all of a sudden, here it was happening to me.” He is not militant, understand, but he did complain. A year ago, he might not have.

He stopped off at the radio station long enough to tape a few off-the-cuff remarks on the Lakers game for his show and swap barbs with a friend. He whipped by an exclusive tailor’s shop to pick up a new four-button suit with flared trouser legs, wolfed down a steak at the Marriott Motor Hotel, where some of the Lakers were just finishing their pregame meal (“Take it easy on us, Lou, we need one bad”), and finally went back to the apartment to rest up and think of Jerry West.

The game wasn’t much. West hadn’t even made the trip to Atlanta, he was so worn out. Hudson, cheered on by four WAOK cheerleaders waving cards that spelled out WE WANT SUPER LOU, scored the first basket of the night for the Hawks on a layup and wound up with 11 of 18 from the field for 25 points. His man, rookie Dick Garrett, scored 10. The Hawks won, 121–107. Hudson wasn’t even breathing hard as he stripped off his uniform and stepped under the steaming showers. While the writers hung around for interviews in the Hawks’ dressing room, play-by-play announcer Skip Caray came through the door with a fistful of dittoed statistics on the game. “Did it again,” Caray said.

“Who””

“Me. I gotta start writing Lou’s name on my sleeve.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Here’s the real Lou Hudson, right here,” he said, waving the final statistics. “You remember Gregor moving around a lot, and Davis on some layups, and Caldwell stealing the ball. So, the game’s over and you start to recap it, and you say, ‘Leading the Hawks were Gary Gregor and Jimmy Davis with 19 points apiece, Joe Caldwell with 15 . . .’ And then, you look down and you say, ‘Er, ah, incidentally, folks, Lou Hudson had 25 points.’ You don’t even remember he was out there.”