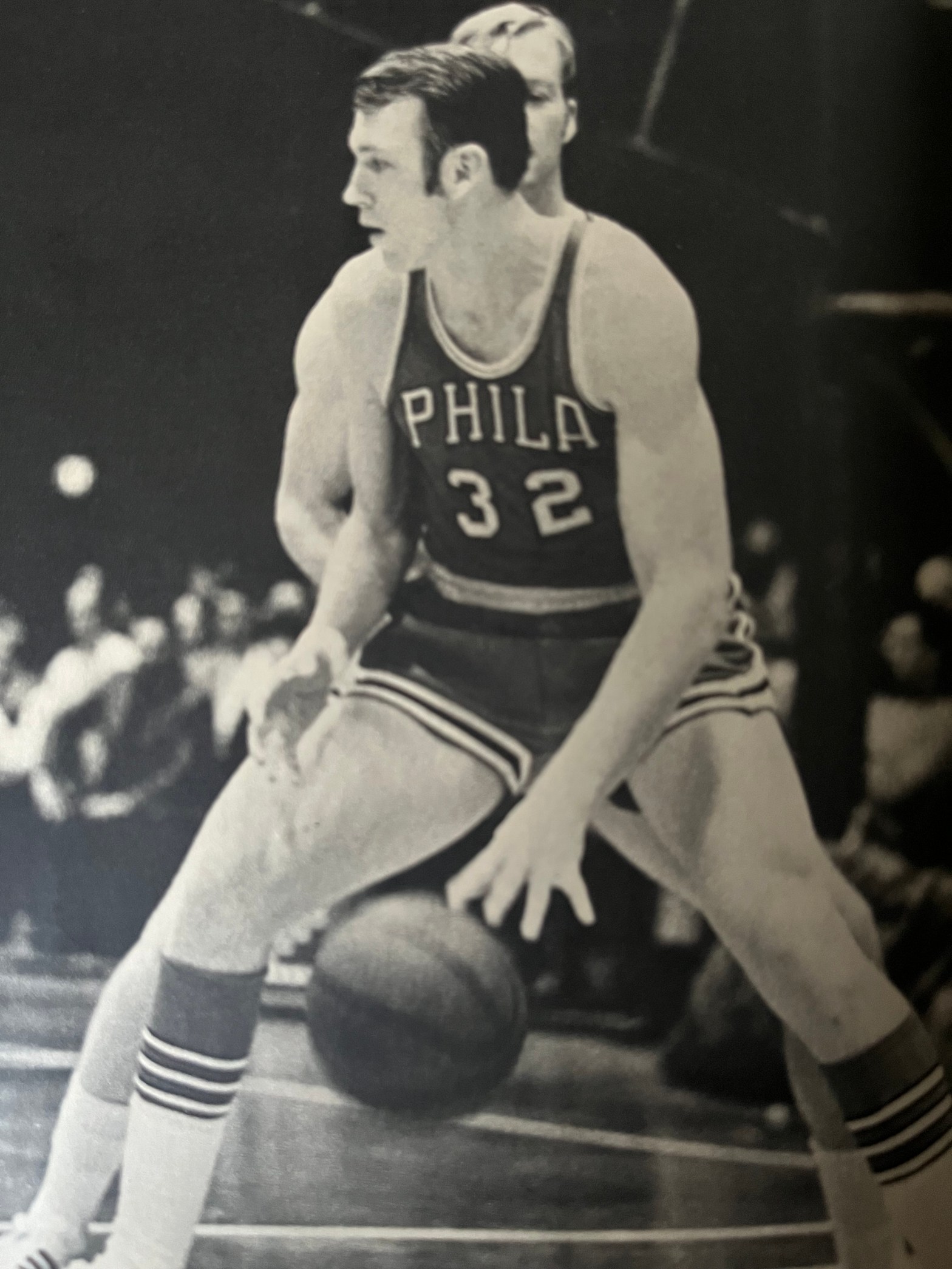

[In the Philadelphia 76ers’ 1968-69 yearbook, the preseason capsule description for Billy Cunningham starts with: “Suffered broken right wrist in third game of Eastern Division semifinals against New York on March 27 at Palestra and injury showed its effects on shallow bench hurt the 76ers in Boston series . . . Arm stayed in cast eight weeks . . . Since then, weightlifting and series of exercises prescribed by Dr. Charles Parsons, the team’s, orthopedic consultant, brought the arm into complete repair . . .”

But there was a lot more to the 25-year-old Cunningham’s prospects that season than the mended wrist. With the team’s long-time star Wilt Chamberlain now playing in Los Angeles, Cunningham, the 76ers’ former sixth man off the bench, had been elevated as the new face of the franchise. Not only would Cunningham start ballgames, he would double his playing time and serve as the team’s first option on offense.

Cunningham, like all great players, didn’t buckle under the pressure and ended the season ranked near the top of several offensive categories. In this article, from the Pro Basketball Almanac 1970, writer Bob Rubin takes a look at how Cunningham made the transition in 1969 from bench player to first team All-NBA star.]

****

When Wilt Chamberlain decided that Philadelphia was a drag and had himself traded to Los Angeles before the start of last season, he left the 76ers bereft—or so said most experts. “After Wilt was traded, the best the papers could say was we’d be a more exciting team without him,” said forward Billy Cunningham. “That’s like somebody fixing you up with a blind date and then trying to hide what a loser she is by saying she’s a great dancer.”

In case no one ever told you before, don’t believe all you read in the papers. The 76ers fooled everybody by making a strong run for the hotly contested Eastern Division title, finishing second with an excellent 55-27 record, only two games behind champion Baltimore. (The Wilt-led Lakers finished the regular season with an identical record, and they didn’t have to face the far-tougher Eastern teams as often as the 76ers).

How could Philadelphia sustain the loss of Chamberlain’s scoring and rebounding power so relatively easy? For two main reasons: one, a complete change in philosophy and approach to the game, and two, the transformation of Billy Cunningham from the team’s sixth man to one of the game’s top rebounding, scoring, and, above all, clutch-shooting stars.

“Oh yes, Billy was our top pressure player,” says 76er coach and general manager Jack Ramsay, who may lose his star to the [ABA] Carolina Cougars in two years. “He seems to come through more often than anyone else with the big field goal. When we were down to one opportunity, we usually went to Billy, and he came through . . . oh, I couldn’t tell you how many times.

“This takes a special quality on a player’s part. Confidence certainly has a lot to do with it. So does the ability to get your particular shot, and to improvise if it doesn’t work out the way you planned it. Billy would improvise, he would do it time and again.”

The first thing Cunningham has to say about his role as the 76ers’ man on the spot is that he wishes they had never gotten on the spot in the first place. “I’d rather walk off the court ahead by 20 points,” he says. “But when these pressure situations do come up, I’ve got to admit they offer a great challenge to me. I have to work as hard as I possibly can to get as good a shot as I can.

“We usually try to work some kind of play, but if that breaks down, you’ve got to go on instinct. Are you going to try to drive and perhaps get fouled, or stop short and take a jump shot? You have to react without thinking, because you usually have only three seconds or so to make your play. You have to kind of time it yourself in your head. I was fortunate last year in that I usually reacted the right way.”

There wasn’t much Cunningham didn’t do right last year—in the beginning and middle of the game as well as in its closing seconds. At 14.3, 18.5, and 19-point scorer in his three seasons as a supersub before Wilt’s departure, the 6-feet-6, 215-pound Cunningham, whose bony frame belies his surprising strength, stamina, and durability, lifted his average to 24.8 points per game to rank third in the league. His 1,050 rebounds, which ranked 10th in the NBA and nearly doubled his previous season high, paced the 76ers in the area where they most missed Chamberlain. And Cunningham’s 3,345 minutes played were topped by only five men. Billy’s peers were highly impressed, even the hard-to-impress ones like Laker superstar Jerry West.

“I have to admit I was a little skeptical about Billy,” says West. “ I mean I didn’t know whether he could do the job as a regular, because he had been coming off the bench ever since he came into the league. But he really showed me something, the way he went from a spot player to a guy who could do a lot of things, the things that make a team win. It’s not just a matter of scoring. Lots of guys score. But Billy scored when he had to, and not many do that. And he rebounded very well. He’s a great competitor, and there’s no way you can measure that.

“I think it’s an overused expression, but in Billy’s case I believe it fits, because as far as I’m concerned, he just never quit. You know he’s going to get his share of points and rebounds every night, because you know that he’s going to be working like hell every night.”

Cunningham today is an all-star forward. Ramsay says, “I can’t think of anyone I’d rather have, so I guess that makes him No. 1.” But, ironically, Billy himself is the first to admit that were Wilt still on the team, he’d probably still be sixth man. And he wouldn’t be unhappy about it, for he never pined for a chance to start.

“I was happy,” he says. “I knew nothing else as a pro. Oh, at first I wanted to start, because when you first get out of college, you still think the starting five is pretty much it with everyone else just sitting on the bench. I didn’t know how much the pros depended on the bench. I had a lot of jobs to do as sixth man.”

But he had more tasks, far more, to perform as a regular on a Wilt-less team, particularly after Luke Jackson, who was being counted on to provide much of the rebounding load lost when Chamberlain left, was sidelined with an injury. Without their two monsters, the 76ers went from one of the biggest, strongest teams in the league to one of the smallest. But if the big men’s absence hurt in the muscle department, it helped in other ways. For one thing, it allowed the smaller, quicker 76ers to run as they never could before. And it opened up the middle of the court for Billy Cunningham to exploit.

“I had more freedom with Wilt’s absence,” Cunningham says. “Wilt always played the low post, close to the basket, and that’s the area I had always operated best in. With him gone, it gave me the opportunity to work inside and out, because our pivotman began to play the high post and set up picks for the forwards and guards.

“And, of course, I got new rebounding responsibilities with Wilt gone, plus the additional playing time. Then when Luke got hurt, our game changed completely—offensively, defensively, our whole thinking. We used to feel we could overpower the other team, that we could give them one shot and get the rebound. But with Wilt gone and Luke hurt, we had two different kinds of zones and pressure defenses. We had to force the other team to make mistakes, because if we let them shoot, they’d probably get the rebound. And on offense, we became a fastbreaking team, where the year before, we were a slow-down, look-for-Wilt, penetrate, get-the-good-shot, take-your-time ballclub.”

Both the team and Cunningham made these fundamental changes in their games remarkably well. As previously mentioned, there was a good deal of skepticism among the experts about whether they could. Cunningham, himself, confessed he had some doubts about his ability to consistently go 40-45 minutes when he was used to playing only about half that long.

“I was worried,” he said, “but it didn’t bother me at all. I was afraid at first that if I really played hard, I’d get tired. But when we got into the exhibition games and I was playing a lot, I realized that you get a second wind, and as the season progressed, I came to the conclusion that it’s a lot harder physically to come off the bench as a sixth man than it is to start. When you go in off the bench, you’re cold when everyone else has already worked up a good sweat and is loose.”

Some doubted Cunningham’s ability to survive as a full-time member of the NBA’s backboard jungle. They conceded that he has remarkable leaping ability (“amazing for a white boy,” says Baltimore’s Gus Johnson with a laugh), but saw him as a gazelle that would be trampled by the league’s mastodons. What did Billy think?

“I tried not to think about it,” he says, laughing. “If I really had thought about it, I might have taken a second look at the whole thing. No, seriously, I always was a good rebounder through high school and college. In fact, I got my nickname (Kangaroo or just Kang) from the North Carolina public relations man because I jumped so well in college.”

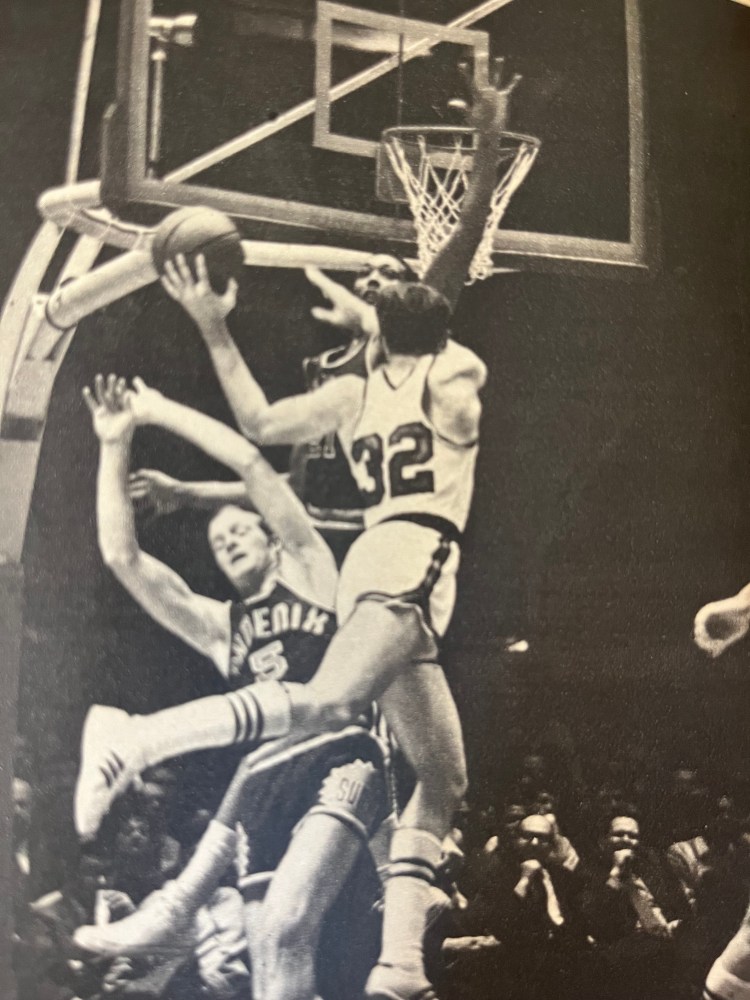

Billy is particularly effective on his offensive backboard, which is somewhat of a lost art in the NBA. “I think the toughest offensive rebounder I’ve ever seen is Bailey Howell,” he says modestly. “He just keeps going and going and going at the basket. I try to do it by positioning myself. After you’ve played with the same guys for a number of years, you begin to get a pretty good idea which side the ball is going to come off on if they miss. So, I simply try to work for that position when the ball goes up. Rebounding is really a matter of positioning more than anything else, I think.”

Cunningham’s rebounding kept the 76ers alive in a lot of games against bigger clubs. His shooting, particularly in the closing seconds, won a lot of them. Sometimes it would be a jump shot swished in from a distance, but more often the decisive field goal would be a driving, twisting, hang-in-the-air, crazy-looking hesitation layup through the heavy traffic under the basket. “He hangs in the air like he’s defying gravity,” says 76er teammate Wally Jones. “He takes a beating and hangs in there, and that’s really what the game is all about. When the pressure’s on, so’s Billy.”