[This story, pulled from the January 1990 issue of the magazine Philly Sport, looks back at Pickles Kennedy. The name may not ring a bell. But Pickles was all the rage in Philadelphia basketball during the late 1950s while sharing the backcourt at Temple with another all-the-rage Guy Rodgers. The two were double trouble for opponents, and from all indications, the NBA was waiting intently to sell a spicy brand of Pickles for many years to come. As this capsule scouting report put it: “Pickles Kennedy, Temple, 5-11—“Best small man since Slater Martin,” says Eddie Gottlieb (Philadelphia Warriors). Dynamic, peppery, hustler on defense, and a fair shooter. He could be the playmaker type the pros covet.”

But, as this article recounts, Pickles’ peppery skills never translated to the pros. He played only briefly with Gottlieb’s Philadelphia Warriors, then spent several years competing in the Eastern League. Pickles’ failure in the pros made no difference to the writer of this piece, B.G Kelley. He preferred to focus on the magic that was Pickles Kennedy at the Palestra stealing the show in the Big Five. Kelley never forgot his basketball idol, and he went back in 1989 to take one last enchanted look at number 3 from Temple.]

****

There was this one magnificent moment among many magnificent moments. This one came when he swiped the ball with the hands of a pickpocket, then dribbled quick-as-a-snakebite, past the one St. Joe’s defender, hippity hop, zipping ‘round him as if he was nailed to the floor, kicking it on out downcourt with a whole lot of shaking going on, crossing over, and beating another Hawk, the ball hot in his hands, then snaking in to the hoop—a 5-feet-11 guard with electric-quick moves—and finally finishing off the moment with a driving deuce.

Wow!

That was the stuff I wanted to copy. I was in the Palestra for the first time in my life this winter night. And I had a dream: I wanted to play in the Big Five, here in the Palestra before 9,000 throbbing fans, just like Bill “Pickles” Kennedy had done this night. Where others on the court, such as St. Joe’s Bobby McNeill and Joe Spratt, were merely hot, Pickles sizzled. Watching him with the pill in his hands was like listening to Jerry Lee Lewis. Great balls of fire.

He scored 30 that night. But it wasn’t just his bull’s-eye jumper or his magical mystery tours through the Hawks defense. You see, there was this whole All-American aura surrounding him: the ringlets of blond hair, the chiseled, handsome visage, the confidence of a cocked pistol, the selflessness of a monk.

When I walked out of the Palestra that winter night, I packed that peek into the realm of the extraordinary tight into my memory. And I was willing to respond to that certain kind of sacrifice needed to play like Pickles Kennedy, so assured was I of the plenitude unfindable anywhere else but on the Palestra floor. Kennedy’s electric music-making moves would thrum inside of me every time I took my game to the gym, to the playground. Indeed, it seemed as if his shots were aimed so that this teenager could pick up on them.

****

I am tooling down Pennlyn Pike in pastoral Springhouse, Montgomery County, PA, looking for a two-story colonial that sits on 3 ½ acres, where Bill Kennedy lives with his wife of 23 years, Carol, and their four children. After some distress, I find it, sitting back off the road like some baronial estate, hidden by a huge chestnut tree. A Mercedes 380 SL sits in the driveway. When you are president of a successful business—Access Systems, a computer room floor company—you can indulge in the best.

Pickles opens the door. He is 51 now. Though he still has the wavy ringlets of blond hair and the blue eyes that quiver like light, the All-American looks are gone. A rare disease has punished his body, leaving him with the puffy look of an NFL lineman. But for now, I am filled with the exploits that made Bill Kennedy a two-time Temple All-America.

Over the tea and croissants in his family room, we reminisce . . .

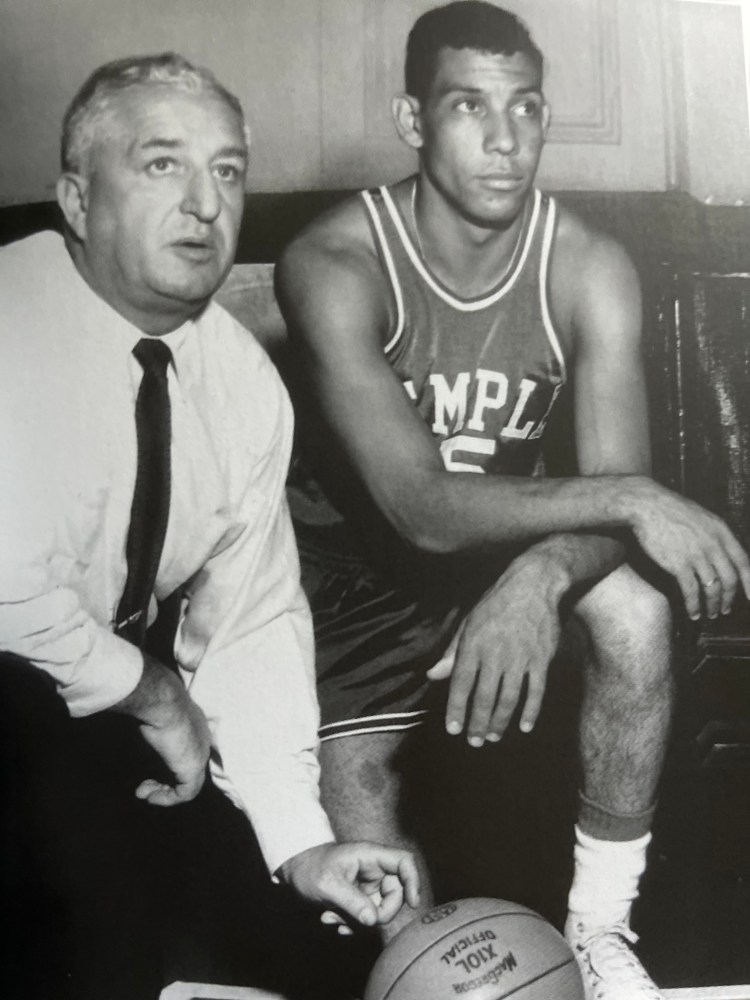

1956. Temple coach Harry Litwack calls his freshman star over to where he is sitting on a chair, smoking a cigar in South Hall, Temple’s creaky, musty, antediluvian basketball court. “I want you to start working out with the varsity,” Litwack confided to Kennedy. Back then, freshmen were not permitted to play varsity sports. Kennedy’s eyes popped open like headlights. Litwack’s varsity counted All-American Guy Rodgers among its penthouse crowd. “I want to put you up against Guy,” Litwack told Kennedy.

Pickles didn’t tell Litwack, but secretly he was in awe of Rodgers. “I saw him play one day,” says Kennedy, “and the defender went for the ball as Guy was dribbling it upcourt. Guy simply took the dribble real high, over the defender’s head, and went down and laid it in. He was the greatest ballhandler, better than Bob Cousy.”

The next day at practice, Litwack told the yearling Kennedy to guard Rodgers. The competitive fervor in Pickles crackled with the intensity of fire. The first time Rodgers brought the ball upcourt, Pickles thieved it from him. By God, this was heresy in South Hall. Smarting like a spoiled kid who just had his allowance pinched, Rodgers threw—and connected with—an elbow to Kennedy’s chest. Hello! Pickles was nobody’s wimp. He had grown up on the streets of Mayfair in the Northeast. And he responded. “I punched him.” Litwack nearly swallowed his cigar. “Hey,” he yelled to Kennedy, “come over here and sit down.”

It would be the last time Pickles Kennedy would sit on a Temple bench.

By his sophomore year, Pickles and Rodgers would be quick-drawing shots, side-by-side, on opponents who couldn’t load up nearly in time. Everyone knew about Rodgers. But Kennedy had to show ‘em. He hit the b-ball scene here running and never stopped to let the Palestra fans catch their collective breath. He wasn’t quite the sharpshooter—but who was?—that Hal Lear had been for the Owls a few years earlier, but he was the complete package: a good shooter, a terrific ballhandler, an aggressive driver, a solid defensive player. He was the perfect partner for the All-American Rodgers.

And perfect they were—well, almost—in 1958. With their hard sneaker soles squealing against the Palestra floor like cars laying rubber, fueling a fastbreak that always seemed like two-on-none, Rodgers and Kennedy ignited the Owls to a 27-3 record and to the Final Four—where they went up against powerhouse Kentucky and its icon coach, the silver-haired, silver-tongued Adolph, Rupp, in the semifinals in Louisville. It turned out to be a game with Twilight Zone treachery to it—if you were a Temple fan, that is.

Temple led just about the entire game; in fact, with 43 seconds remaining, the Owls held tight to a 60-57 lead. Then two plays involving Kennedy turned a Temple win—and a chance at the national championship—into a cosmic injustice.

Kennedy reels out the final moments of that game from memory: “A play with 40-some seconds left took the game from us. I was coming down on a fastbreak with Guy, gave Adrian Smith (a Kentucky guard) a fake at the foul line, and took the ball to the hoop. Smith spun around and jumped in front of me. The ref whistled me for a charge. That was no charge. I made a layup, too.”

Smith drained the two foul shots to cut the Owls’ margin to one. Sixteen seconds later, Rodgers bricked a foul shot, and Kentucky collared the rebound. With 14 seconds left, the Wildcats’ Vern Hatton drove the baseline, worming his way past a couple of Owl defenders, and flipped up a reverse shot. Kentucky led 61-60.

Temple called a T. The Owls huddled around their coach. “Litwack set up a play for me,” says Kennedy, “the old three play where each guard comes off the forward for a drive to the hole. Temple inbounded the ball and began to weave into their pattern, each Owl keenly aware a trip to the championship game could be at the end of the play. Forward Mel Brodsky had the ball. Pickles ran off him. Brodsky shoveled him a pass, but Pickles bobbled the ball, and as it was heartbreakingly hurrying out of bounds, Kennedy chased it, spinning with the frenzy of an eggbeater. Tweet. Kentucky ball.

“I saw the play some years later in slow motion,” says Kennedy, “and I realized two things. I was too close to Mel, and the pass was too hard. At the time I took it personally. I blew the pass; I lost the game. I cried.”

****

It was the next year, 1959, and Kentucky came to the Palestra to play the Owls. Pickles was a one-man gang, unstoppable, money in the bank, even though the Owls were a bankrupt team, on the way to a 6-19 record after having lost Rodgers and the rest of that Final Four team to graduation. Still, Rupp was worried that Kentucky would explode for one of those games where he could beat the powerful Wildcats all by himself.

“Give him to me, Coach, give him to me,” Dickie Parsons, a naïve sophomore from the hills of Kentucky, was begging Adolph Rupp to let him guard Kennedy. “I’ll stop him, Coach. I’ll stop him for you.”

Early on, Pickles took the ball, his body tight with adrenaline. Parsons bellied up. Kennedy rocked left, then went right, past Parsons so fast the kid looked like he had rigor mortis. Pickles stopped and popped. Swish.

Parsons picked Pickles up at halfcourt. Kennedy stutter-stepped a dribble, freezing Parsons to the Palestra floor, and drove the lane, flipping up a half-hook, half-push shot. Doosh. Pickles was doing exactly what Rupp had feared: putting a dead-eye spin on an Owls upset win.

Rupp ordered Pickles double-teamed and sent senior Bennie Coffman out to help Parsons. “Pick him up three-quarter court,” the Baron demanded. They did. But Pickles came at Coffman and Parsons with gunslinger eyes and a quick-draw dribble, splitting them with the hand speed of a magician and the foot speed of a dancer, pushing the pill ahead and down the middle. Kentucky All-American Johnnie Cox came over to pick Kennedy up, and Pickles ripped off a perfect pass to Cox’s man, Bernie Ivens, cutting to the hole. Two. Rupp erupted: “Triple-team him!”

“It was my greatest game,” says Kennedy.

It wasn’t so much the 27 points and nine assists he tallied, but more the effort against a great Kentucky club, against double- and triple-teams, against all odds, really.

No, the Owls didn’t win, falling to the Wildcats, 76-71. After the game, Rupp was heard to say about Kennedy, “I swear, he’s better than Guy Rodgers.”

Better than Rodgers? That might be a stretch, but certainly Bill Kennedy stood on the same high ground. By his senior year, he was everybody’s All-American, the ultimate backcourt creator. On his final visit to Lexington that year, he was honored in pregame ceremonies. He had tortured Kentucky throughout his career, and now Rupp wanted to pay him respect. One of the gifts he received was a year’s supply of pickles. (“My sister started calling me Pickles when I was three,” explains Kennedy, “for no apparent reason.”) After accepting the gift, the usually shy Kennedy took the microphone and said to the Kentucky crowd, “My only regret is that I wasn’t called ‘Cadillac.’”

****

And to think, all these years, we thought Delilah sheared Sampson of his strength. No, say some researchers, it was a rare neurological disease that attacks the muscles called myasthenia gravis. If it sounds summa cum serious, it’s worse. For Bill “Pickles” Kennedy, it almost took him out for good.

“About 10 years ago,” he begins the tale of this unpleasant odyssey, “I was playing tennis with a friend, and after whiffing some shots, he says to me, ‘Bill, you ought to get your eyes checked.’ Then I began to get double vision, so I went to an eye neurologist.” He was told he had myasthenia gravis.

“I never heard of it, but I learned it was traced back to Biblical times, that some doctors thought it was the cause of Samson losing his strength.”

Pretty soon it got worse. “I couldn’t open one eye,” he says. “I couldn’t swallow, I couldn’t go up the steps without tumbling back down. All my involuntary muscles were basically dead.” He began to have trouble just walking and talking, and eventually he couldn’t work.

What happened, according to Kennedy, was this: his immune system was overproducing antibodies, and they began to coat the nerve receptors, preventing the nerve impulses from getting through to the muscles, thereby sapping his strength.

He went to a specialist at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania who told him he wanted to remove his thymus gland. A normally active thymus gland helps to build the immune system. Pickles’ thymus was as active as a circus. By removing it, the doctor hoped it would help to slow down the immune system—retard the production of antibodies—and send the disease into remission. In December 1982, Kennedy had it removed in a five-hour operation, which left a 10-inch scar roaming down his breast bone and what felt like a stake in his heart when he woke up. “Uh, the pain,” he winces.

Catch 22. For Kennedy to continue to keep the disease under control, he needed a little help from some unlikely friends: steroids. Huge doses—80 mgs. a day—were required at the beginning. “The disease in incurable,” he says, “and the steroids help to depress the immune system even further. If I didn’t take them, the disease would weaken me again.”

Happily, the disease is under control today, although Pickles says, “I can still go off any time.” However, he is down to taking lower doses of steroids—10 to 20 mgs. a day. “I won’t be playing guard for Temple anymore,” he jokes, “but I can get in 18 holes of golf.”

Still, there has been one clearly visible side effect. The steroids have left Kennedy looking bloated, though he is not nearly the size he was five years ago, having shed 40 pounds down to 207. But when you’ve taken Robert Redford looks to the bank every day, it is hard to deal with what you see now. Pickles smiles and nods his head, “Yeah, it’s tough sometimes to look in the mirror.”

****

It was another winter night long ago . . .

There weren’t any magnificent moments. The truth is, the moments were sad. He entered the game with about four minutes left, and the Philadelphia Warriors winning handily. He looked Lilliputian—lost among Chamberlain, Arizin, and Gola—and seemingly, eternally tethered a yard or two short of the skills needed to stick in the NBA. His moves now appeared robotic, calculated, programmed not to make a mistake. There was none of the instinctive wizardry— that quick-as-a-heartbeat crossover dribble, that lightning-rod first step, stop and pop and swish, those serpentining drives down the lane and up for two, that behind-the-back pass to a teammate on a crackling fastbreak—that he stylized at Temple. He took two shots this night—both missed. It was his only year in the pros: seven games, 52 minutes, 12 points.

I walked out of Convention Hall that winter night and never saw Bill “Pickles” Kennedy play again. Yet, I called in the chips on that dream he had stirred in me three years earlier at the Palestra. Though I never did play exactly like him, I did play in the Temple backcourt and I did wear the number, 3. Yep, Pickles Kennedy had aimed his shots where this once-upon-a-time teenager had picked up on them. For me, he would never be just any basketball player.