[The Miami Heat may be in deep trouble in their championship series with the Denver Nuggets, but what a magical ride the 2022-23 season has been for an NBA franchise that’s hard to root against. At least for me. That got me thinking of the 1988 expansion Miami Heat and all of the talent that since has lit it up in Miami.

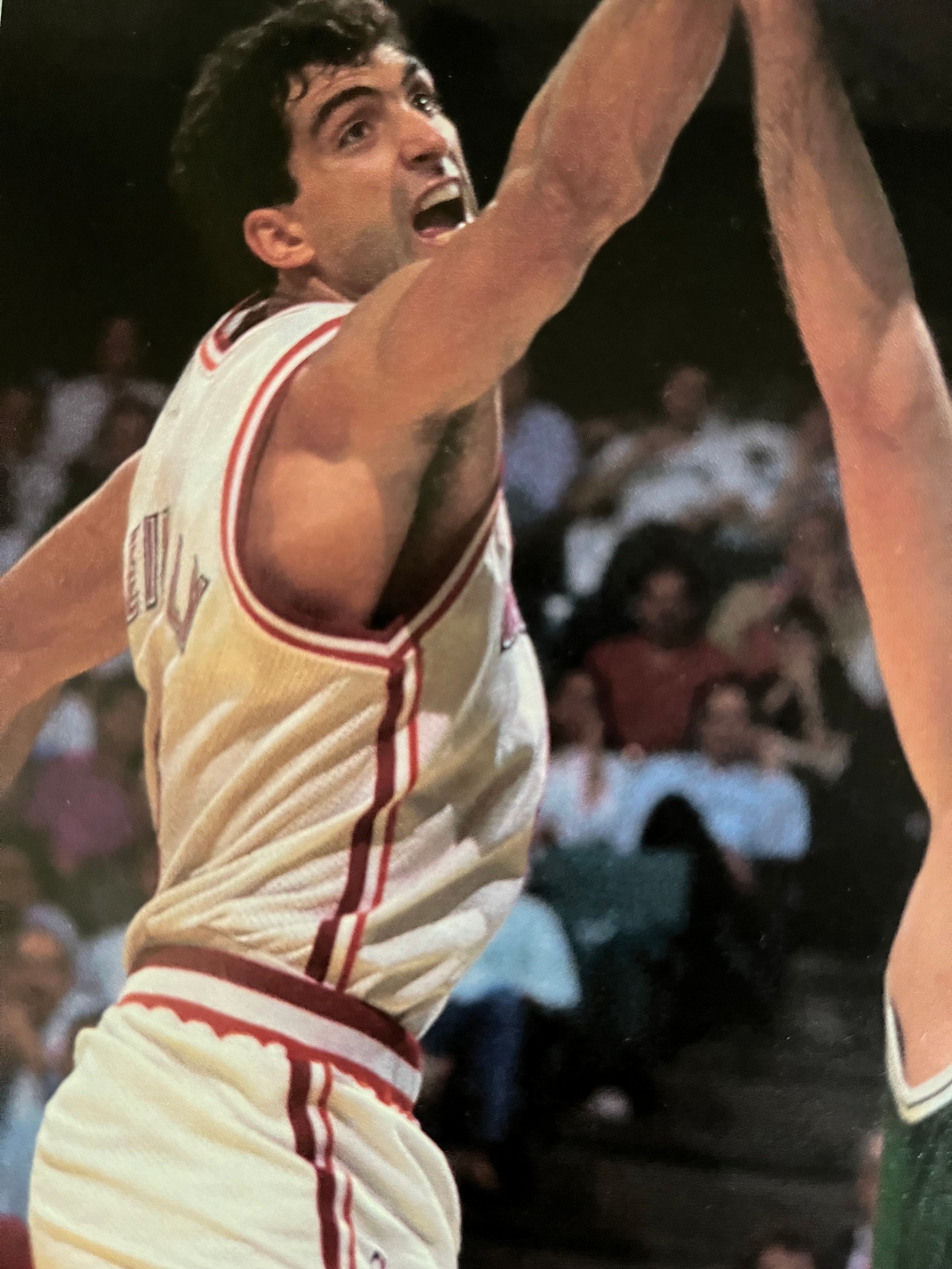

Here’s one of those talents, Rony Seikaly, the franchise’s very first draft choice. Miami took the 6-feet-10 Syracuse University star first (ninth overall) in the 1988 NBA Draft, and this article, from the April 1991 issue of the magazine Hoop, looks at Seikaly’s brief honeymoon with Miami fans, his early development as an NBA center, and his then-unique journey to the NBA. The byline belongs to Bill Needle, the former PR director for the Atlanta Hawks. Needle, who passed away in 2018, was later a Cleveland sports radio talk show host and the play-by-play radio voice of the Kent State Golden Flashes.]

****

There is supposed to be a honeymoon period for expansion teams and their players. It’s a time of reduced expectations, where fledgling teams are allowed to develop without facing severe criticism. Often this honeymoon period lasts as long as four or five years.

Rony Seikaly’s honeymoon with the fans of the Miami Heat lasted somewhere between 10 minutes and three weeks. As the first draft choice in the history of the franchise, he was Miami’s designated target through much of the Heat’s first season in 1988–89. If Miami lost big, it was Seikaly’s fault. If the Heat came close only to lose, it was Seikaly’s fault. Few rookies—especially rookies on expansion teams—received the scrutiny Seikaly did in his rookie year.

To their credit, Miami fans cheered Seikaly as robustly when he won the American Airlines NBA Most Improved Player Award in 1990 as they booed him in 1989. “People just expected him to become a star immediately,” said Heat executive and former NBA great Billy Cunningham. “But it just doesn’t work that way.

“When we drafted Rony, we knew he was a project. He had played only four years of competitive basketball (in the US), and we knew we were going to have to be patient with him.”

It’s not as though Seikaly’s rookie season was a disaster. It’s just that the expectations were high and that Seikaly made gradual progress, rather than an immediate explosion. Playing 78 games in 1988-89, Seikaly averaged 10.9 points and 7.0 rebounds as a rookie, his rebounding average the best among 1988 draft picks. As a starter in 62 of those games, his averages were even better—11.6 points and 7.5 rebounds. But because he wasn’t Kareem or Hakeem or Patrick, Seikaly often heard from Heat fans who were patient about every area of the team’s development but the pivot.

“Too many people tend to evaluate rookies on the first half of their first season,” said Heat director of player personnel Stu Inman. “Some of the ones doing so well at the start, you forget about two years later; and some of the ones who struggled through the first year emerge two years later.”

That Seikaly emerged to play in the NBA at all is one of the league’s most interesting stories. Son of an international businessman, he spent his youth in the strife-torn streets of Beirut, Lebanon.

One story of Seikaly’s childhood tells of a terrorist blowing up the stairwell in the family’s apartment building. Seikaly had just taken the elevator instead of climbing the stairs. Another of Seikaly’s childhood experiences consisted of walking the streets of war-riddled Beirut carrying a submachine gun.

The family moved to Athens, Greece, when Seikaly was 10. He began playing basketball as a student at the American Community School at the age of 15. In America, some hoop prodigies are already playing pickup basketball against local college and pro stars by the age of 15. In Athens, Seikaly’s game was “polished” under the occasional glances of a teacher.

“It was totally unorganized,” he said of his early activity. “The referee would be our math or physics teacher. But I seemed suited to the game. Every day I played, I got better. It came naturally to me.”

At age 18, Seikaly—by then standing 6-feet-10—participated in Coach Jim Boeheim’s Syracuse University basketball camp on vacation in the U.S. He enrolled at Syracuse several months later.

Although unschooled in much of the American-style game, Seikaly possessed impressive athletic skills that would blossom as his college career unfolded. By the time of the 1988 NBA Draft, his athleticism—despite only four years of organized basketball experience—occasionally had him mentioned as the top overall pick. The Pacers, who had the second overall choice in 1988, brought Seikaly to Indiana for testing.

“Seikaly graded the highest of all the players we tested,” said Pacers GM Donnie Walsh. “We found out he’s a fabulous athlete. He had incredible stride; it was over 10 feet once he got going, and that’s up there with Edwin Moses. It was really impressive.” Although never timed in the sprints, Seikaly said he ran the 220-yard dash in the 25-second range while at Syracuse.

But despite his potential, as well as impressive college credentials and his ninth overall pick status, it was a tough first half of the season for Seikaly in 1988-89. The Heat were losing, and Seikaly was hearing booing.

“As a rookie, I hated playing at home,” Seikaly recalled. “As a rookie, the attitude was, ‘Get me on the road as fast as you can.’ I’d get the ball down low. I was constantly asking myself, ‘Should I make a move or not? If I miss it, they’re going to boo me. Or, I might get fouled. If I get fouled, I go to the free throw line. If I miss the free throw, they’re going to boo me again.’ I didn’t know what to do. I was playing games with myself.”

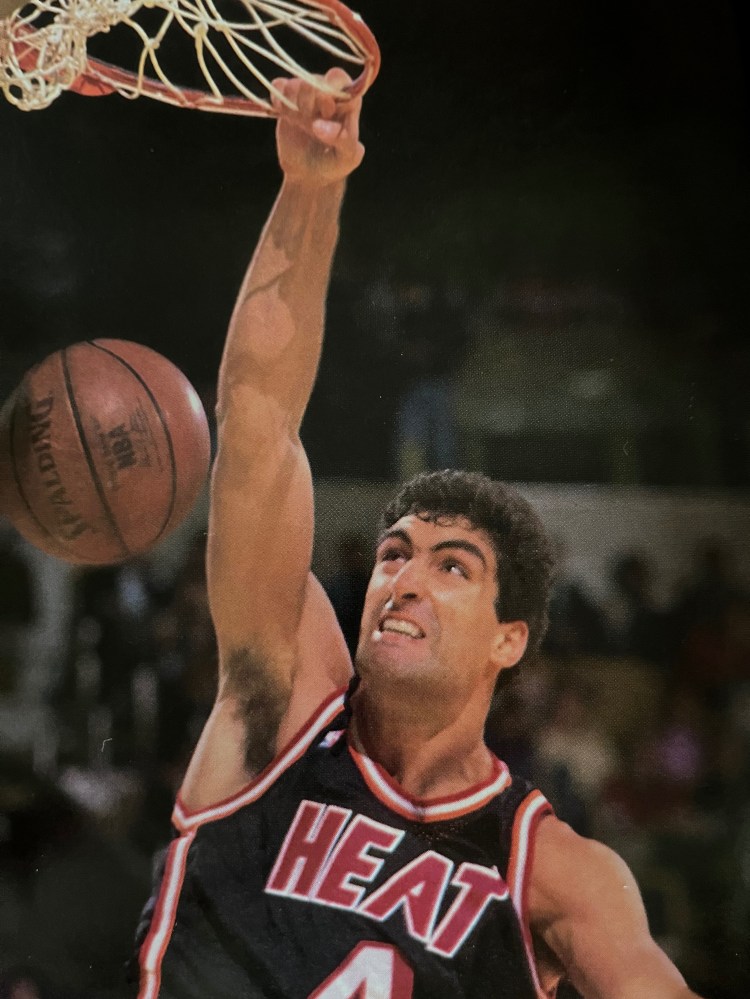

Last year, in his second season, Seikaly knew exactly what to do. And the head games he played were more often with those of opposing centers, rather than his own. He led the Heat in scoring and rebounding. His 10.4 rebounding average was sixth-best in the NBA. He was one of six centers to make the NBA’s top 10 in rebounding. The other five were named Olajuwon, Robinson, Ewing, Parish, and Malone. What a difference a year makes?

“It takes big guys longer, it’s as simple as that,” said Heat coach Ron Rothstein. “Look up and down the league. Robert Paris was a bust when he broke in with Golden State. They wanted to run (Patrick) Ewing out of New York. (Mike) Gminski’s finally come into his own in Philly after nine years in the league.”

And Seikaly is starting to come into his own in Miami. As the NBA moves to quicker, faster centers in the Olajuwon-Ewing-Robinson mold, Seikaly’s name is often mentioned when experts speak of the centers of the 1990s.

“He’s got good foot speed and quickness in the low post,” said Heart assistant coach Dave Wohl. “Those are two attributes that enable you to get things done. He has a nice mix now of shooting and moves. He has good fakes; he knows how to set himself up.

“You can’t play him one-on-one in the post anymore without him getting a good scoring opportunity,” Wohl added. “He has his confidence down there. Now he has to apply the same intensity and concentration at the defensive end. Perhaps the greatest measure of Seikaly’s improvement since his rookie year is that, like most maturing people, he knows what he doesn’t know. In the NBA, it takes more than superb athletic skills and a 10-foot running stride to make it to the top.

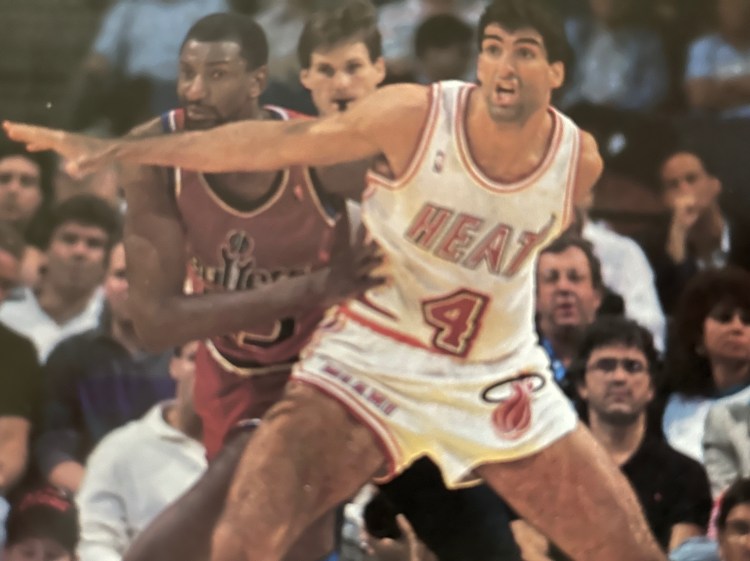

“Physically, I see a lot of players with a lot of skills just like me,” he said. “Everyone is strong and quick and can put the ball in the basket. I can do all those things. The difference is the mental aspect. I have to learn to play different players, defensively, and be tough enough to play the same way every night.

“Every game is a learning process,” he added. “Every time I play, there’s something new. I’m still learning. There are a lot more facets to the game that I have to conquer before I become a complete player.”

Fortunately for Seikaly, the Heat, and their fans, Seikaly is also finding out he has the desire to excel that should carry him the remaining distance between “improving” and “great.” He spent many afternoons this past summer working on his conditioning and stamina by running laps at the University Miami track stadium—under the hot Florida sun.

“Rony is so much better as a player now than when he came to us as a rookie, it’s hard to believe. He deserves a lot of credit,” said Rothstein.

“He’s a little bit more knowledgeable about the game,” said former college roommate and current Heat teammate and point guard Sherman Douglas. “He’s more hungry. Rony wants to be a great player. He wants to be an all-star type player.”

“The tenacity and will needed to jump that chasm (between “improving” and “great”) is tremendous,” said Wohl. “That’s why so few make it. But that’s what Rony needs to do, and when he does, that’s when we can talk about him belonging with the great centers.”

And if the time comes that Seikaly takes his place among the NBA’s best centers, perhaps the fans of Miami will pay him back for the rough treatment of his rookie season by inviting him on a second honeymoon.

They didn’t have much of a first honeymoon, so the second one should last for a decade.