[In 1973, when Tom Meschery published Caught in the Pivot: The Diary of a Rookie Coach, I couldn’t put down the paperback. Meschery provided such a rare look inside of an ABA franchise. There was nothing else like it.

As the years have passed, though, so has my high opinion of the book. It’s a diary, stupid. It’s one man’s opinion about the 1971-72 Carolina Cougars and the transition from one generation to the next. In this case, the next—the Me Generation—brought a different set of values to the court and, to Meschery’s consternation, placed money before the game.

Meschery’s critique of the Me-Generation remains important to consider for anyone interested in understanding the NBA-ABA years. His perspective leads you to the main generational rifts and describes how the influx of big money distorted this simple YMCA game and turned it into popular entertainment.

Caught in the Pivot also offers an eyewitness view of rookie Jim McDaniels’ ill-fated jump from ABA Carolina to NBA Seattle. The magazine Popular Sports 1973 All-Pro Basketball excerpted the pages from Meschery’s diary that chronicle McDaniels’ decision to heed his agent Al Ross and leave the ABA and his Cougar teammates behind. Here’s the story.]

February 10—For days nothing happens; the regimen of professional basketball life seems, at times, endlessly boring. And then it all comes crashing in at once.

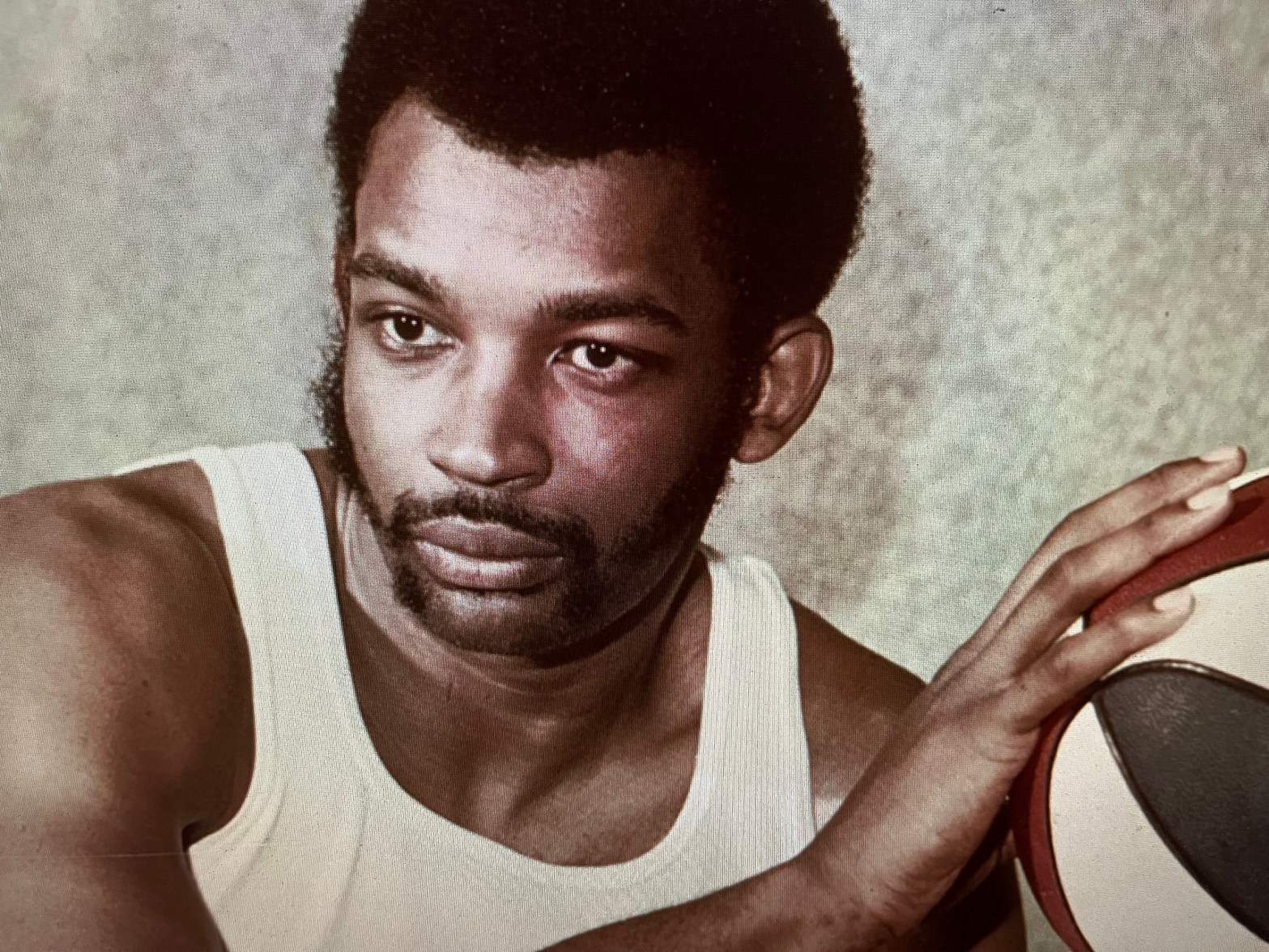

We were ready to play Kentucky. At least I thought we were. I arrived at the office at 10 AM. We would travel early to Charlotte, where the game would be an hour-and-a-half drive from Greensboro, the team’s home base. Buddy, our trainer, told me that Mac (Jim McDaniels) had called and said he had some financial difficulties and would not be able to make the trip on the bus. He would follow us down. When we arrived, however, Mac was not there for our shoot-around drills. Mac did not say he wouldn’t make the practice. Although it would cost Mac a fine, I was still not worried; call it stupidity or naivete.

At that point, Carl Scheer, the Cougar general manager, who had driven down with Tedd Munchak, our owner, came over and told me that there was big trouble. He said Mac had financial difficulty, something to do with tax shelters. Carl added that Mac was so disturbed that he was thinking of not making the game tonight. I was paralyzed. What the hell was going on? Were we ever going to have a moment’s peace in the midst of what was already a frustrating season just to think about the game of basketball?

After the shoot-around, Munchak, Scheer, and I went back to my hotel room. It was there that I was filled in on all that had happened during the last two days. Jim had called to see Munchak and Scheer on the ninth. He was down in the dumps about his agent in New York, Norman Blass, who according to Mac, had not protected his money well enough with tax shelters.

I could see where Mac would be worried. He is by nature a bit of a miser about his money, worrying about each dollar as if it were a thousand. He doesn’t gamble like most pro players and, unlike many players, does not spend his money on extravaganzas. Mac had called Blass that morning and told him of his concern. Blass said he would fly down right away. Then, five minutes later, Mac called Blass back and told him that he was letting him go as his attorney.

Munchak then explained that on Tuesday night, he had taken Donna and Jim out to dinner. He told them that he would see to it personally that Mac’s money was invested in the same tax shelters that his millions were. He told them that they would never have to pay a tax again. After dinner was over, Munchak took Jim and Donna to their home, where they talked further. Munchak said that they seemed to be relieved and happy about things. It was then that Mac asked Munchak if he would go to the airport the next day and tell a Los Angeles-based agent named Al Ross to return to the West Coast; that everything had been taken care of.

Munchak’s reply was a valid one, but now seems to have been a mistake. He told Mac that he would have to do that himself. He said that he didn’t want to get involved with Ross, and that there were some things that Mac would have to do for himself. With that, Munchak left Jim and Donna, happy that all had been resolved so easily to the satisfaction of all.

The next morning, Munchak was sitting on the sofa in Carl’s Cougar office. Things appeared to be back to normal. Munchak looked up to see Mac and another man walk into the office. They wanted to talk to him.

“Who’s this guy?” Munchak asked in his gruff, to-the-point voice.

That guy was Al Ross, and he was there as Mac’s brand-new agent.

“What about our conversation of last night?” Munchak wanted to know.

He’d thought about it, Mac said, but had decided to let Ross represent him.

Without saying a word, Munchak walked across the room, picked up the telephone, and called his accountant in Atlanta. He canceled his instructions for Mac’s tax shelters “for the time being.” Then, he turned to Carl and said, “Get it in writing” and walked out of the room. He would not talk to Ross until he saw in writing that he was Mac’s agent.

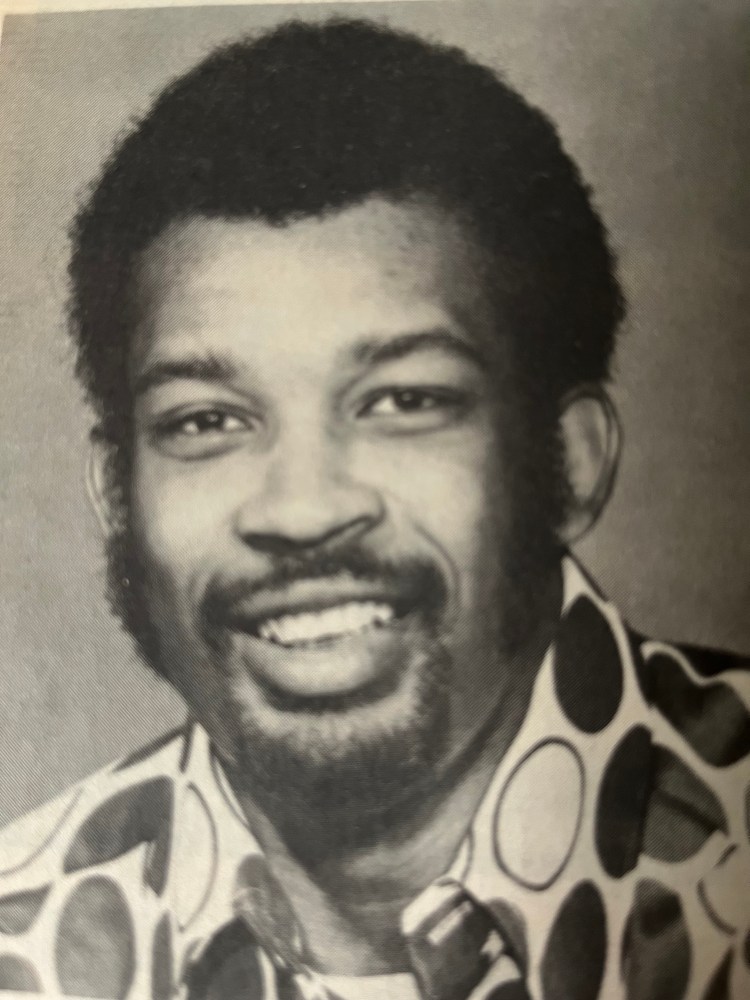

We sat in the room and wondered what was happening. Between Munchak and myself, we must have smoked a dozen packs of cigarettes. The room was a cloud in which, three rather forlorn men sat, each with his own premonition of the gloomy days ahead. What bothered us most was Mac’s threat to leave the team entirely and go to Los Angeles with Ross. Al Ross is a name well known in professional basketball. He Is the same Al Ross who represented Spencer Haywood when he jumped from Denver to Seattle in 1970.

Ross is no dummy. He appears totally “with it,” too “with it” to be believable as one of the wives who met Ross at Jim and Donna’s house was later to say, “He’s too mod to be for real, there’s not enough conservative in his appearance to look honest—he’s weird.”

He is also big with flattery. Another wife, who met him at McDaniel’s home spotted him for a “phoney,” as she said. He told her she was a good-looking woman and asked her to take off her coat, so that he could see the rest of her. With these kinds of remarks, Ross could really fill your head, as she said, but she had barely got out of bed to take her husband to the bus for Charlotte and knew just how she looked that morning when Ross “laid it on.”

The first thing that came to my mind that afternoon was that Mac was looking to jump leagues. It also crossed my mind that the awesome figure of Sam Schulman was rising to the West. In the NBA, McDaniels was Seattle’s property. What a horrible thought; what a pain all this was!

Carl called Mac on the phone. He told Mac he had to be down for the game. He cautioned him not to leave. Mac agreed to come for the game, but he said he didn’t know what frame of mind he’d be in to play. I wondered about that, too. His body would be there, but I wasn’t sure that his mind wouldn’t be in more remote regions.

With all the talk and speculation flying around the room, Munchak mentioned Gene Littles as an example of a ballplayer giving his guts, and he was also the lowest paid on the team. We all sighed wistfully. The mention of a guts-out, low-paid ballplayer these days brings tears to the eyes of management. We decided to give Gene a bonus. Munchak felt that we shouldn’t wait but call him up and give him the bonus right on the spot. We decided on $2,500. We called Gene and asked him to come down to the room. The poor guy was probably nervous all the way over. Whenever management calls a player and asks him to come in, whether to the office or hotel room, it usually means bad news—a trade, a cut, or something of that nature. Gene was truly stunned when we gave him the extra money. But Gene really deserved it.

We lost to Kentucky, and, as all of us suspected, Mac played poorly. He just didn’t have it defensively or on the boards. He scored, but Mac could score if he had two broken legs and had to shoot from a stretcher. But his mind was not together for the aggressive, unselfish parts of the game. I had put a lot of time and effort into Mac’s development as a pro. And after that performance, no matter what was on his mind, I wanted to take him out into the alley and beat his brains in. A lot of abuse had come my way as I persisted in letting Mac develop as a player. My stomach was turning over. This was a letdown of unbelievable proportion for me.

After the game, Joe Caldwell came to me to ask if he could miss practice tomorrow. He had some business in Washington, D.C. that was costing him $500 a day. He told me that he had to go, and despite what I said, he would accept the fine for missing practice. With all that was going on, it was enough straw to break my back. All the outside influences were more important than the game. It was all happening, guys were businessmen before they were players. Management had birthed a monster, and it flourished all over the leagues.

Mac’s wife and new attorney were at the game. They left with Joe Caldwell in Mac’s new Cadillac. I suppose that these were the beginnings of the questions as to whether Joe had been involved in the whole mess.

Februarys 11th

I called Mac into the office before practice at the local high school gym. I asked him point blank what was going on. I pleaded with him to level with me. I asked Mac who his beef was with—his ex-agent Blass or with the Cougar management? He said that it was a contract problem. So, this business about taxes was only a subterfuge. Something bigger than taxes was going on. I felt a sickness in my stomach; Mac was trying to get out of his contract. That had to be it. Mac told me that he felt management was trying to screw him, and that he had called New York and fired Norm Blass, his agent. He had then hired Al Ross, who in Mac’s words “would take no shit from the management.”

I asked Mac if he were planning to leave town. He answered that if he didn’t get “things” straightened out this afternoon, he was going to Los Angeles. I asked: How could he leave his teammates? Couldn’t it wait to the end of the season only 25 games away?

Showing no outward emotion, he said that it was a matter of principle. He felt he was getting a screw job. I did not want to go into it any further. I had 11 other players to worry about who were now warming up on the floor. I would know all the details soon enough. I left Mac asking him to promise to call me if things weren’t resolved that afternoon. He promised to call me. He never did.

That was the last time I was to see or talk to Jim McDaniels.

The time between the end of practice and the telephone call from Carl Scheer, signaling the conclusion of his meeting with Jim and Al Ross, was filled with nervous apprehension. I wish that I could’ve sat in on that conversation. Like my name, Thomas, I am filled with doubts about that which I cannot see with my own eyes. This is true, especially concerning management. I can’t break myself of my old distrustful habits toward owners and managements. They are the feeling of many professional athletes.

Cari finally called at 5:30. He told me that Jim would probably not be playing with the Cougars anymore. It was as he suspected; they were simply trying to renegotiate Mac’s existing contract. They wanted a contract like Joe Caldwell’s. They even boasted of using Joe’s contract as a model. Either Joe or Joe’s lawyer, Marshall Boyar, had given Ross a copy of that contract to study. They knew of all the benefits that Joe was getting. And they wanted about the same things for Mac. Al Ross had presented him, Carl said, with 16 points (demands) and stressed that they needed an answer by seven that evening, only four hours later.

It all became very clear. Ross didn’t want an answer. He wanted only an excuse to get Mac out of town. Carl told me he would fill me in later. We both had to hurry to speaking engagements.

I couldn’t imagine going to a banquet and saying all the little chit-chatty things that you talk about at sports banquets. This was not the time for sports cliches. It was not the moment to talk about how great our athletes are or to extol the virtues of our great sport. This was a time of bitterness for me, and I felt like going to the banquet and crying in a loud voice, “This whole business stinks of whores and pimps. You fans who look upon these fine athletes as though they represent models for your own children are looking in the wrong direction. Many of you look in disgust at the young who search after new lifestyles, who lament the senseless bombing of other people, who cry that something is dreadfully wrong with the system. But these are the real models, these are the young men of tomorrow, not our pro athletes. The pro athlete is a product of the commercial state. He is an anachronism.”

I returned homesick of myself. Instead of truth, I had given platitudes and funny stories. I had joked and laughed. I had put on a hilarious mask. I had promoted the sport like a robot performs his master’s commands. At the banquet, I had sold eight tickets for a future Cougars’ game. I had made fans for a sport that was fast becoming less than a sport.

Carl came by later that night. His eyes were red, sunken into his head. He looked gaunt, worse than when I had seen him after his abdominal surgery at the beginning of the season. We sat in the living room, and he told me all that happened that afternoon with Mac and Ross in the office. Carl said that he felt like an idiot sitting at this desk dutifully writing down each demand as it came, point after point from the lips of Al Ross. Mac had sat in the corner, silent and unmoving. Occasionally, he looked up, but, as Carl put it, “It was as if he was staring through me; as if we had never met before.”

Mac wanted his $1.5 million contract paid over 15 years instead of 35. He wanted incentives—$25,000 for making the playoffs, $25,000 for most valuable player. He wanted $100,000 in a life insurance policy and his contract’s yearly payments changed to a once-a-year lump sum. He also wanted Mr. Munchak’s personal guarantee on his contract. Finally, Mac wanted, according to Al Ross, $50,000 cash immediately for an aggravation fee for having to put up with all the crap he claimed that he had had to put up with playing for the Cougars and living in North Carolina. Crap, hell, I thought. We’ve all had to put up with crap. Who hasn’t felt some aggravation during this season?

By about the tenth demand Carl said he became sarcastic. He said things like, “Perhaps $25,000 is not enough, how about $30,000?” Or, “$50,000 is a rather low figure, don’t you think?” When the 16 points had been stated, Carl asked if there was anything else. There was. Mac was upset that his name was not nationally known, that he had not been given national publicity. Ross referred to Mac as ”this man so blessed with talent, etc., etc.” Carl told me that at that moment, Ross could have told Mac that he was Jesus Christ and Mac would have believed it.

At the complaint that Mac had not received national coverage, Carl stuck to his low-keyed, sarcastic tack. “I was not aware that they are giving national publicity to a last-place team. Gee, what place are we in? Are they covering last-place teams nationally now?”

Also, Mac claimed that the local newspapers had put pressure on him, which they had. I have previously discussed the stupidity of the writers, particularly Mitch Mitchell. In the same breath, however, Ross complained that I had not given Mac enough playing time. He was averaging better than 37 minutes a game. The minutes would have been higher had Mac not been in serious foul trouble in many of the games in the early part of the season. Then, Ross went on to say that I put too much pressure on Mac. These last two statements seemed to me to be contradictory. The man wants more playing time and less pressure. It doesn’t work that way. It doesn’t happen otherwise.

Was there any appealing to Mac’s sense of loyalty to his teammates? To the rest of this season only 25 games away? To a season that was finally turning around to favor us making the playoffs? There was none, Carl said. The guy was worried about points and rebounds. “If you had been there, Tom, you would have thought you were talking to another Elvin Hayes.”

I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t even begin to believe that I had so totally misunderstood Mac’s personality, the kind of man he was. Once Carl looked at me with some exasperation and said, “Won’t you ever realize that Mac is gone? He’s not coming back. He won’t play anymore.”

Later, Carl said, “You can’t believe, can you, Tom, that a Black man would not trust you, would not like you because you were white? It’s too much a part of your ego or something that it won’t allow you to believe that.” Carl was clearly at the end of his rope.

Joanne, my wife, was furious. She sat there, staring at Carl, incredulous while he told his story. She wanted to go to Mac’s house right then, to talk to Donna, Mac’s wife. She wanted them to tell her that they were doing the right thing. Joanne was very hurt. She thought that she and Donna had been more than just associates through the team; she felt that they were friends. I talked her out of it, and I’m sorry that I did. She needed to express her feelings in her own way. It would have done no good, at that point, however. Even while we talked, Jim, Donna, and Ross were winging their way to the West Coast. They had left Greensboro at 10:00 P.M. that night.

EPILOGUE

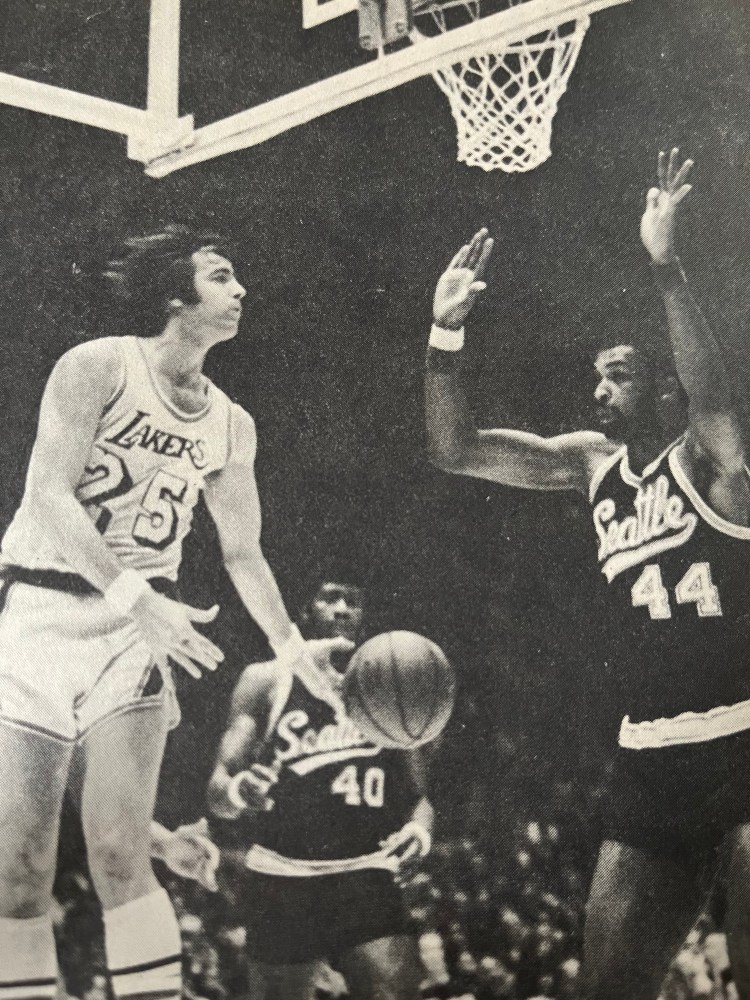

At the time this diary was written, the final destination of Jim McDaniels was as-yet unsettled. A week later, Jim registered under an assumed name in Seattle’s Olympic Hotel. A week after that, he was suited up in Seattle’s green-and-gold uniforms, and lawsuits between the Carolina Cougars and the Seattle Super Sonics were flying hot and heavy across the country.

In North Carolina, Jim McDaniels was looked upon as a traitor. The newspapers described him as an ingrate, a selfish kid who sold out his Cougar teammates just as he had deceived his university by signing a professional contract while still an undergraduate. The editor of the Greensboro Daily News went a step further, analyzing Jim in his distinctive antebellum manner as a poor Black man who had been duped by self-seeking whites at every stage of his life. The gentle, young man who had been lauded at the beginning of the season for his familial devotion was quickly forgotten. In his place stood a figure of unsurpassing villainy.

In the Northwest, Jim was given a standing ovation by an overflow crowd of Seattle fans who came to see Sam Schulman’s most-recent coup over the fledgling ABA. To them, he represented the Sonics’ long-sought-after man to fill the gap in their center position. The Seattle press painted Jim in glowing colors. The villains were the unscrupulous managers of the Carolina Cougars and the unethical signing tacticians of the ABA.

At the season’s end, I resigned as coach of the Carolina Cougars, citing as my reason a growing resentment to the burgeoning grasp of big business on sports. That feeling is still with me. But with a few months to reflect, I am beginning to regain my sense of humor. There’s a comedy in all that has happened. It can be easily overlooked because of how close it rests to the borders of tragedy.

Where I was, on the inside, I watched grown men, scurrying back and forth, as if possessed, to prove the prevailing axiom in sports that “Winning is Everything.” I watched with amazement as owners in both leagues, paid astronomical salaries to unproven talent. On the other side, I saw veterans demand salaries which far-exceeded their talents. I watched the media unhesitatingly create superstar myths, and fans bending over backwards to appreciate those myths. I sat in front of my television and watched Pete Maravich’s hair move to the left, then move to the right, and finally score the winning basket. And I began to laugh longer and louder than I had laughed for a year.