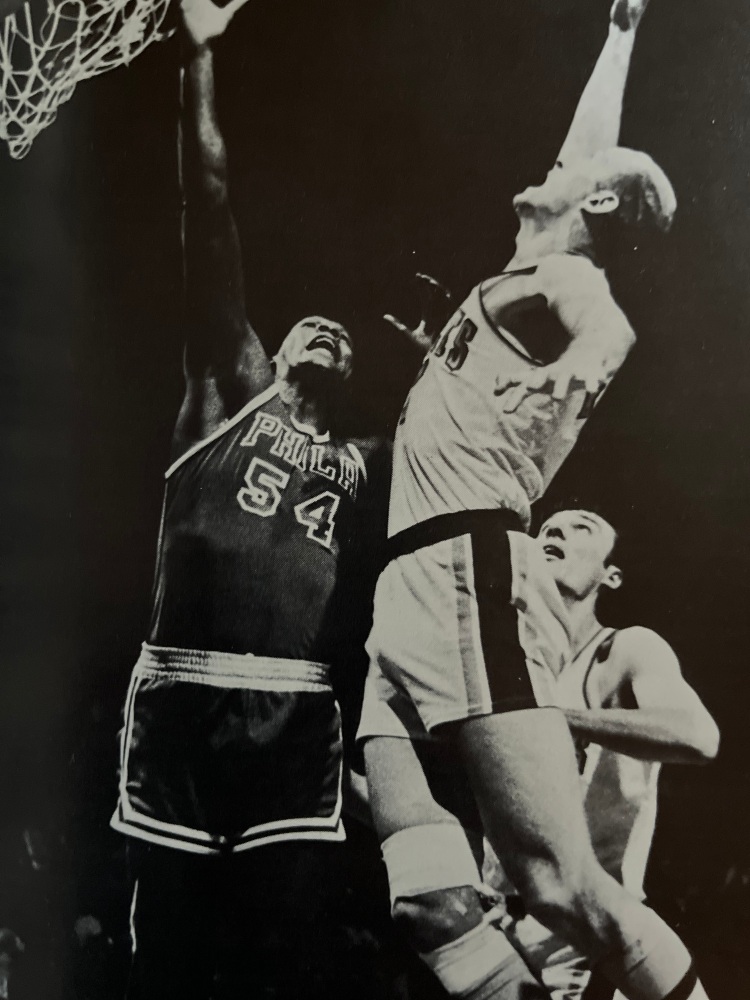

[I once interviewed Luke Jackson. He was at home in Texas working on his car when I called. His extremely personable wife insisted on getting him. “Hello,” he snapped, clearly not in the mood to talk 1960s hoops. The interview edged along until I asked about players back then acquiescing to “horse shots” to numb their chronic aches and pain and keep playing. Jackson finally let loose, answering sternly that the blankety-blank injections were behind his serious 1969 leg injury, the one that derailed his once-promising career. Jackson was never the same, mainly because the surgery went so poorly. As one of his former teammates told me, “Luke came back with a big hole in calf.”

In this pre-injury article from the 1969 magazine Pro Basketball Almanac, the Philadelphia 76ers are banking on Jackson to be their new all-star-level starting center. The Sixers have just dealt the disgruntled Wilt Chamberlain to the Los Angeles Lakers, and Philadelphia’s new coach Jack Ramsay is high on Jackson’s versatility. Big Luke could stand his ground inside and trade elbows with the best seven-footers and, having played forward, also could set up on offense away from the basket, if needed. For Dr. Jack, the ultimate tactician, Jackson and his soft jump shot would pull the seven-footers out of the paint and allow the franchise’s new go-to guy Billy Cunningham to slash to the hoop. In fact, when I interviewed Ramsay years later about his first 76ers’ squad, the first words out of his mouth were: “It’s too bad we lost Luke, that ruined our season.”

Pushing the injury aside, Jackson was one of the NBA’s better big man while teamed with Chamberlain. Here’s writer Bob Rubin on why Jackson, if only he had stayed healthy, could have left more of a mark on the NBA.]

****

“Adjusting to forward is tough, learning to make your moves facing the basket after you spent all your life making moves with your back to the basket . . .” Luke Jackson, November 1965

“I had spent four years at forward. I thought I was learning to master the position, to play it as it should be played. I told the coach I really didn’t care to move back to center . . .” Luke Jackson, 1968

Luke Jackson has no choice. The reason the Philadelphia 76ers were willing to trade Wilt Chamberlain to the Los Angeles Lakers last summer for Archie Clark, Darrall Imhoff, and Jerry Chambers was their belief that Jackson could fill the 7-feet-1 hole left in the middle of their lineup. Everyone in the league, including the 76ers, seems to agree that if Philadelphia is to have any chance of winning its third-straight NBA Eastern Division championship, Jackson has to fill that hole. “He’s the difference between winning and losing for them,” said Atlanta Hawks coach Richie Guerin, “the difference between finishing first, second, or third.”

Jackson, obviously, is a man on the spot. For starters, he has to replace Wilt Chamberlain, a job, no harder than, say, selling Edsels or following the Mormon Tabernacle choir on stage. In truth, no one replaces Wilt Chamberlain. Like the Eiffel Tower or Tiny Tim, Wilt is one of a kind, unique. But new Philadelphia coach Jack Ramsay is asking more of Luke than was ever asked of Wilt.

Ramsay would like to be able to swing Luke from center to forward and back, depending upon the particular game and situation. Since the two positions have entirely different responsibilities, what Ramsay is asking, in essence, is for Luke to be two different ballplayers. No one in the NBA has a greater load on his shoulders.

Once Luke would have welcomed the opportunity to exchange elbows and hips with the league’s giant centers. He had always been a center, and a good one, from the time he was a high school all-state choice in Bastrop, Louisiana, through his college career at Pan American in Edinburg, Texas, during his impressive contribution to the United States’ 1964 Olympic victory, and into his rookie year with the 76ers in 1964.

His NBA debut impressed people. At 6-feet-9 and 240 pounds, his head smoothly shaven, he looked like a Mr. Clean. But, to the admiration of some of the tough, old pros, he didn’t play like Mr. Clean.

“If I’m ever tempted to make a comeback, I’ll think of Jackson,” said Bob Pettit, who was in the final season of his distinguished career. “You play him 10-20 minutes, it’s bad enough. But he never stops on defense. If he feels you tiring, look out.”

Bill Russell, who was calling himself an old man back then, agreed. “I have to turn the other way to breathe hard,” Russell said, “because when he senses I’m tired, he goes wild. He dominates a game when he gets that way. Is that any way to treat an old man?”

Then a funny thing happened to Jackson’s promising career as a pivot man. Right after the 1965 All-Star Game, the 76ers got Wilt from San Francisco, and Luke had to move 20 feet to the side. “It was like going back to kindergarten,” he said of the shift to forward. He and Willis Reed of the Knicks, who was making the same adjustment, commiserated with each other. “You know how good a shooter he is,” Luke said, with misery-loves-company glee. “Well, he went one-for-10 against us and oh-for-eight against Los Angeles. It was unbelievable.”

Reed and Jackson adjusted, finishing one-two, respectively, in the Rookie-of-the-Year poll. Jackson got used to playing forward, teaming with Chamberlain to form one of the most-imposing frontlines in the history of the game. Just a look at the frowning Jackson could be intimidating. “The first time I saw him, I wanted to hit him with a technical foul,” said one referee. Luke frowned, but he was happy.

Now he’s not, and it’s understandable. “Yes, I’m reluctant,” he said. “But who knows? Maybe it will turn out to be the best thing for me.” He managed to laugh as he said it. It wasn’t very convincing.

You can’t really blame the 76ers for asking Jackson to make the shift. It is a simple fact of life that almost no one wins consistently without a good center. The center is the man who must get the rebounds essential to the fast-breaking offenses that most teams favor, score, defend against both the monster assigned to him and any guards and forwards audacious enough to approach the basket, set up picks, pass off—he must be the team’s rallying point, its hub.

Because of his importance, the center must avoid foul trouble, not at all an easy thing to do in the face of his multiple defensive responsibilities. He must be durable, for often he will be asked to play the full 48 minutes or close to it. He must therefore learn to play with pain. As if this isn’t difficult enough for any center, Luke Jackson goes into the meatgrinder with two outstanding handicaps: First, he is inexperienced; and second, he’s at a height disadvantage.

Wilt blots out the sky at 7-feet-1 and a fraction. Nate Thurmond is a hair under seven feet. Russell is 6-feet-9 and aging, but when it counts still has the reflexes, jumping ability, court sense, and competitiveness that puts him on a par or higher than his bigger opponents. Those three men have the ability to completely dominate a game. Luke must not let them dominate. Is there any wonder why he’s reluctant?

When Jackson learned that Imhoff, a center, was one of the players coming to Philadelphia in the trade, he had a fleeting hope that he wouldn’t be asked to move. “I was kind of hoping that they’d say Imhoff would be the regular center and that I’d stay at forward and be his backup when he came out of the game,” Luke said.

Ramsay quickly informed him otherwise. “I agreed if I had to move, I had to move,” Jackson said. “It will be hard work adjusting, but I’m sure I can make it.”

Ramsay thinks he can do it, though, of course, he’d look silly saying anything else. “Luke has shown in the past that he can play center in this league, and play well,” the coach said. “I know he’ll do the job. And while it would be to our advantage to be able to swing him, if he can’t play both, the center position takes priority. I know Luke will give it 110 percent.”

One of the biggest problems Luke faces, learning to shoot with his back to the basket rather than facing it, doesn’t worry Ramsay at all. “But his problem may come in playing defense against the big guy,” the coach said. “He’s not physically, able to dominate a game like Chamberlain, Russell, Thurmond. But after those three, I think Luke comes next. He’s certainly our most-important man. We must have quality performance at center.”

Alex Hannum, who coached the 76ers last year before going to the Oakland Oaks of the ABA, agrees that Luke can make the switch successfully. And he doesn’t have to say it. “I made the statement many times last year that I thought Luke was in the middle of the pack as a center, not a Chamberlain, Russell, or Thurmond, but right up there with Zelmo Beaty and Walt Bellamy in the next grouping.” Hannum said. “I think he can be a more-than-adequate center. You’ve got to have a good backup man because Luke will get into foul trouble, but with Imhoff, that shouldn’t be a great problem. No, I don’t think it will be a tough adjustment at all. I’m sure he’ll do the job.”

Everyone feels Luke can do the job. Here are some other opinions:

Richie Guerin—“I think his natural position is center. What the heck, look at his size. His toughest problem will be getting the feel of the position again.”

Billy Cunningham, 76er forward—“It’s more of a load, more of a responsibility, and a great, great change for him. He was just getting to be a great forward, and now he has to learn to play center again. But with his determination, I think he’ll make it. He gives 150 percent.”

Donnis Butcher, Piston coach—“If they didn’t have Luke Jackson, they might be lucky to make the playoffs. It’s a lot easier adjusting from forward to pivot than from pivot to forward. With Luke, I still think they have a real good shot.”

But the biggest question is Luke’s thinking, not everyone else’s power of positive thinking. It’s his body, and Luke worries. He worries most about playing defense against the Big Three. “I’m giving away size and experience,” he said. “What I’m going to have to try to do is keep that ball away from them as much as possible by fronting them and getting as much help as possible from the forwards.

“Once one of those guys gets the ball inside, there’s not much you can do about it. Wilt Chamberlain, forget it. If he gets the ball in close, there may be times I’ll have to give up a basket to avoid a foul. Yes, that will be my biggest problem—keeping those big guys off the boards and keeping them from dunking on me.”

He’s less concerned about his shooting. “I’ll have to work hard in training camp on learning to shoot with my back to the basket,” he said. “Oh, I’ll get some shots blocked early in the season because I’m not familiar with the habits of the guys defending against me. It’ll be tough for a while, but I’m not going in with a defeatist attitude.”

He’s not exactly dancing in the streets, either. Mention Ramsay’s desire to use him as a swingman, and Luke’s voice takes on a note of pain. “It’s a little confusing,” he said. “You have to keep two different sets of plays in mind. I think when you’re trying to learn one job, you should just concentrate on that one job. But I can see where there will be times that it’s best if I play forward. I’ll do my best.”

That’s the key to Luke Jackson—a desire to always do his best. The 76ers know that what they’re asking is basically unfair to ask of one man, yet because it is Luke Jackson and because they know he’ll try anything if it’s for the good of the team, they’re asking.

“He’s awfully important,” said Hal Greer. “If we’re gonna win anything, he has to have a great year.”

“Luke’s the key,” said Cunningham. “No question about that.”

“I don’t feel any pressure now,” Jackson said just before reporting to camp. But the intonation of his voice made you doubt his words. Then, speaking more firmly, more positively, he added, “I’ll do my best. What more can I do?”