[Willie Sojourner died in a car wreck now almost 20 years ago. But his basketball story deserves to live on, mainly because it’s a real good one. Too bad there’s not a lot that remains that brings out Willie Sojourner and the big personality that charmed just about everybody whom he met along the way.

The best interview still out there ran in a small Utah newspaper called the Lakeside Review on February 27, 1990. Because Sojourner’s basketball journey is glossed over in this article, I’ve bulked up the text considerably by inserting snippets from several other newspaper stories, primarily a story from the Deseret News’ Dan Pattison, who covered the ABA when Sojourner broke into the league in 1971. I also took the rare indulgence of giving the text a little copy edit. It was pretty rough in places.

With that as prelude, here’s to the great Willie Sojourner. In college, they called him Wonderful Willie. Wondrous Willie. Big Willard. In the ABA, they just called him Rainbow. But Sojourner’s greatest claim to fame may be the letter “J.” Julius Erving arrived in the ABA in 1971 with the nickname “The Doctor.” Sojourner, Erving’s teammate, roommate, and good friend, gets credit for adding the “J” to Doctor J.]

****

Being from a poor family of 11 children in a rough Philadelphia suburb, Willard Leon Sojourner chose to make good somewhere else where opportunity knocked a little louder. His choices since then have brought him through life in the limelight of professional sports on two continents, to settle quietly in Roy, Utah, with his wife, three children, two dogs, a cat, birds, and a basketball hoop in the driveway.

The former professional basketball star settled In Utah for the lifestyle, the peace and the people who knew him from his days at Weber State College in Ogden, where he was recently inducted into the school’s Hall of Fame.

Although he never wanted to play basketball as a boy, Sojourner was always an athlete. He loved swimming, football, and track, specializing in the high jump. His goal as a teen was to be the first Black swimmer to win a gold medal in the Olympics. Years later, his track and field skills did take him to an Olympic training camp, but he had already signed with a professional basketball team, disqualifying him from Olympic competition.

In high school, he was voted “most likely to succeed” and best all-around athlete. In his junior year at Germantown High, he actually finished first in the state public school swim meet in the 100-yard butterfly, but was disqualified on a technicality. “I would have won except for going back for my trunks,” he said.

Being poor, Sojourner said all he had to wear in the competition was an old pair of cut-off blue jeans. As he dove in, the shorts came off. He swam back and put them on in the water, caught up with the pack, and passed the other swimmers, winning the race. But the judges disqualified him, saying he touched the bottom of the pool while putting his trunks back on. They gave him second place instead.

It was only in his senior year of high school that Sojourner tried out for basketball. It came at the urging of the basketball coach, who wanted to utilize Willie’s size, (6-feet-8, 225 pounds) and great leaping ability.

Willie hit the court in excellent shape from swimming and track, being the city champ in the high jump in his junior (and later senior) year. He also had good hand-eye coordination, having played both ways on the football team. “I was instantly good,” he said of his belated introduction to basketball.

Because Sojourner only played one year of varsity basketball, most major colleges shied away from him. That left room for Dick Motta from mid-level Weber State College to swoop in and take a calculated chance on him. Sojourner agreed gladly to head West to the mountains and farmlands of Utah. He was glad that it was quiet, relaxed, and laid back. He liked that. “Not too much to do to take your mind off your schoolwork,” Sojourner said. He worked hard and averaged a 3.0 grade level.

Sojourner enjoyed school and wishes now he had concentrated more on academics. “You have to get yourself set for something that you want to do when you finish basketball.” Looking back, he said nobody ever took him aside and talked to him about the future. “You’ve got to have something to fall back on.”

Willie met his wife Jean Trombly, a Michigan native, in the school library during his sophomore year. They hit it off immediately, despite the fact she wouldn’t write his English paper for him and turned down a spin in his brand-new, second-hand car that same afternoon.

They were secretly married six weeks later. Although he was allowed to be married under the terms of his scholarship, they chose [living in conservative Utah] to remain in separate dorms and didn’t let anyone know about the marriage for a long time. Twenty-two years ago, Sojourner explained, interracial marriages were not as common as they are today.

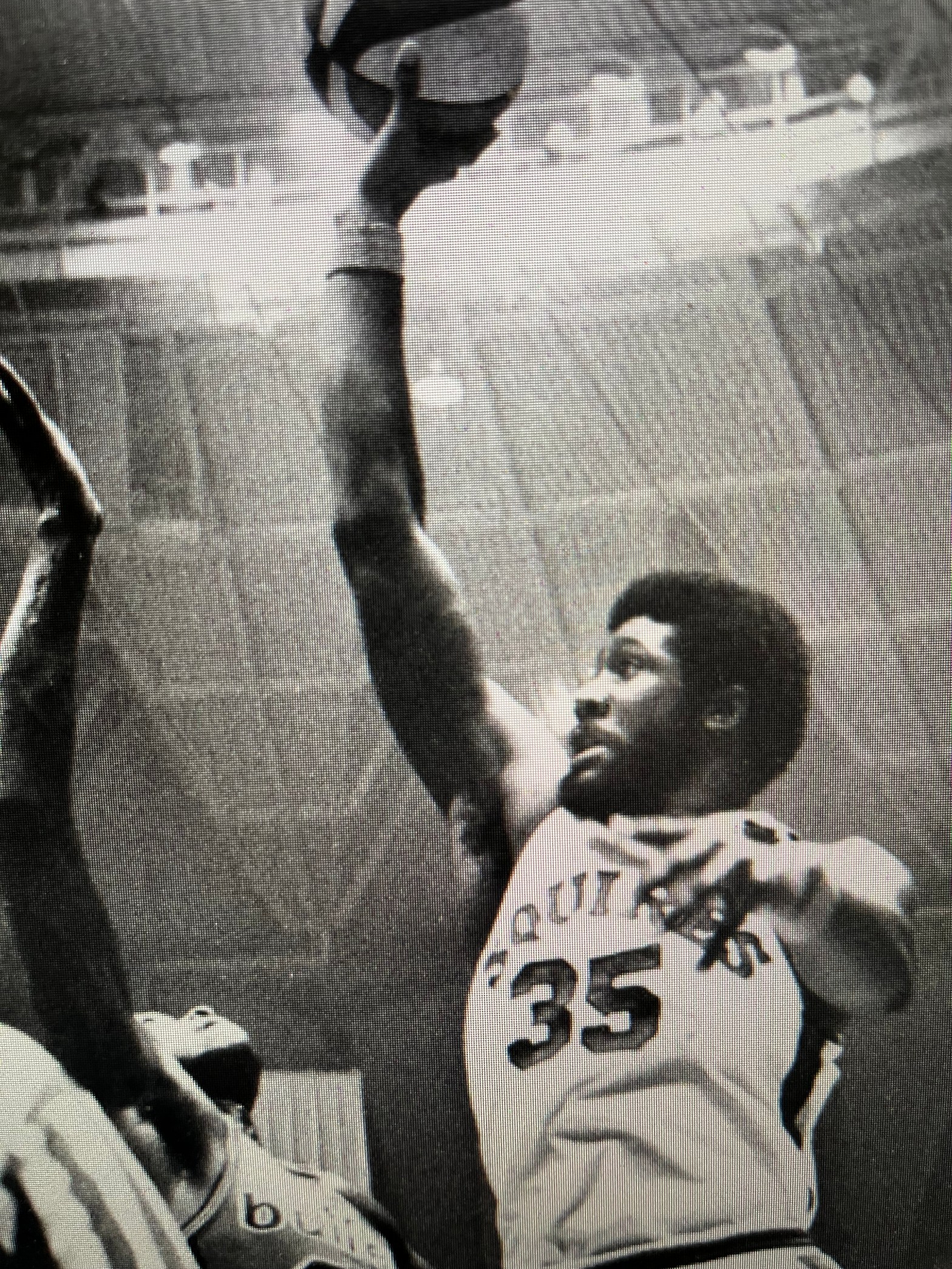

On the basketball court, Sojourner excelled. He led led Weber State to three Big Sky Conference titles and three NCAA tournament berths, averaging 19.3 points and 13.6 rebounds per game over his career.

The pro scouts flocked to Ogden, where his coach Phil Johnson (Dick Motta left for the NBA Chicago Bulls after Sojourner’s freshman years) was waiting with two thumbs up. “Some people are disappointed in Willie, because he doesn’t play outside more,” said Johnson, who would soon join Motta in the NBA. “But he’s a great inside player and, far as I’m concerned, a truly great basketball player. He practically carried us last season.

“I’m sure Willie will be a first-round draft choice next spring, and he might be able to make it at center in the pros. He’s not a razzle-dazzle type player, but he blocks a lot of shots. Whether he scored 16 points or 36, he does a great job for us. Great attitude, easy to coach, improved every year. More than anything else, Willie is a winner, on and off the basketball court.”

Sojourner went to the ABA Virginia Squires in the first round, and Motta’s NBA Bulls grabbed him in the second round. But the Bulls promptly traded his draft rights to the Golden State Warriors, and an old-fashioned interleague bidding war ensued. Sojourner finally came to terms with the Squires for a reported four-year, $440,000, contract, then a hefty deal. The way Sojourner puts it, “I thought I picked the right league because I thought I could play a little more.”

Sojourner arrived for training camp that fall uncharacteristically flabby and sucking air during wind sprints. In some ways, it didn’t matter. All eyes fixated on the magical, never-seen-before aerial show of the Squires’ other rookie: Julius Erving. Sojourner, once in peak condition, struggled to keep pace with the swifter Erving, Charlie Scott, and the Squires’ fastbreaking attack. It wasn’t all his fault. At Weber State, Sojourner had played strictly in a patterned offense that waited for him to set up inside, jostle for position, and call for the basketball.

In the mid-level Big Sky Conference, Sojourner also had been the big man in the middle. An intimidating force. Not in the pros. Sojourner was somewhat shorter, lighter, and initially less refined in the paint than most ABA centers—and it showed. “The centers jump much higher and have a different arch on the ball,” Sojourner explained. “They’re smarter. When they drive to the basket, they have a different arch. They don’t put it up straight. They put it over you.”

As a college high jumper, Willie also picked up a bad habit that was tough to shake. High jumpers usually take a step and gather themselves before jumping. “Coach (Al) Bianchi is trying to teach me to rub up against a guy before I get off my hook,” Sojourner continued. “I used to take a step before I got off my shot. He wants me to go straight up and eliminate the time it takes to take the step.

“Bianchi has been teaching me a lot, and I’ve got a lot to learn. I think I’ll need about 40 games. The game is more physical. It’s hard to believe some of the things that happen [in the pros]. You get away with a lot of stuff. “

Sojourner had his moments as a rookie. Like Red Robbins Night in the Salt Palace. He only played 22 minutes that night, but he hit eight of 12 field-goal attempts back in his adopted home state of Utah, hauled down seven rebounds, and scored 17 points, as well as blocking numerous shots and pretty much dominating the inside action.

As a Provo sportswriter captured the moment, “He has phenomenal control of the basketball. His hands are to the basketball like my hands are to a softball . . . He has such marvelous control that even while he’s gripping the ball, he can softly sail it away to the basket with a floating feather touch that seems to fall through the strings in slow motion. It’s really beautiful to watch—so effortless.

But height—and experience—mattered. In Virginia, Sojourner settled in for two seasons as a backup center behind veteran Jumbo Jim Eakins. Then, before the 1973-74 season, Sojourner (and his big contract) was traded with Julius Erving (and his now bigger contract) to the New York Nets.

Wife Jean intensely disliked the idea of moving from the quiet life in Virginia to the fast pace of the Big Apple. They had their eldest son Chris by then, and Jean did not want to move their family to New York. “She thought we were going to get killed or mugged every day,” he said.

When Jean finally stopped sobbing “I don’t want to go,” they moved to Long Island. His wife really liked it, Sojourner said, although all the neighbors did get robbed, except them.

Sojourner said he and Erving got to be very good friends while playing together. They were roommates while on the road and inseparable at times. But as so often happens, Sojourner said, they’ve lost contact over the years.

Before the 1975-1976 season, the Nets had three viable centers in training camp and needed desperately to cut expenses. (Owner Roy Boe was convinced the Nets would bankrupt him) Sojourner, who just had completed his four-year ABA contract and was waiting to sign a new one, wouldn’t cost the Nets a penny to release. He was the odd man out, and the Nets waived him. So it went in the ABA as the league approached its bitter end.

Sojourner then joined the Lancaster Red Roses in the semipro Eastern League for six months before an invitation came to try out for the basketball team AMG Sebastiani in Rieti, Italy. He was planning to go, but two weeks prior to leaving, the left-handed Sojourner got that hand caught in the fan belt of his car, nearly severing his thumb. He received 42 stitches, and his hand was all bandaged with the thumb positioned over the inside of his palm, leaving only four fingers loose but mostly bandaged.

Sojourner feels he did some of his best playing during his next seven years in Rieti. In fact, he cleared the lane for Joe Bryant, Kobe’s dad. “Joe took over the legacy that was begun by Willie Sojourner, who really helped establish the team,” said Guiseppe Cattani, who teamed with Joe and later was Rieti’s team president.

“Willie Sojourner was Rieti’s basketball godfather,” Cattani continued. “Nobody wanted to mess with ‘Zio Willie (Uncle Willie),’ as we called him. Back then, when Americans came to play in Italy, they were really viewed as legends. They taught us how basketball was played on the other side of the ocean. All kids back then, like me—I was on the youth team—would look up to these players in awe.”

He said he “peaked” there, but at the end of his career in 1983, he and his family were ready to return to the U.S. “We got on the plane, not knowing where we wanted to go.”

They ended up back in Ogden, but were disappointed that the city has deteriorated so much since they left 12 years earlier. Jean found a place in Roy, where they have been since. Sojourner didn’t know what he wanted to do along the lines of employment after Italy. He said he had no skills. “Basketball is nothing you can relate to the outside world, unless you’re a coach. And I don’t like coaching,” he said.

He did not want to enter the field of his college major, sociology, because there isn’t much call for it here in Utah. Besides, he said he couldn’t hold a desk job. “I get restless.”

He worked with aluminum siding until six months ago when he was offered his current job in Elko, working as a carpenter framing new houses to accommodate Nevada’s modern-day goldrush.

Sojourner still plays basketball for fun, but he said it frustrates him to play with guys who are there just to exercise and socialize, not to win. “When it comes to basketball, I am very competitive,” he said.

[Sojourner returned to Italy in September 2005 to coach Rieti’s youth team for a second time. A month later, he crashed his BMW into a tree along a twisty road on a rain-filled night. Sojourner died from his injuries at the age of 57. Before Sojourner’s body was returned to Utah, Rieti held a standing-room-only memorial service for “Zio Willie” in the Palaloniano arena, where he had starred. A month later, the Palaloniano was renamed Pala Sojourner (Sojourner Gym) in his honor, and a memorial was placed at the site of the accident. It read: “To Willie Sojourner—Unforgettable champion of sport, humanity and sympathy. Rieti Forever.” Pretty classy, don’t you think?

What follows are two quick vignettes of Sojourner and his captivating personality, starting with his verbal domination of the 1970 Olympic men’s basketball tryouts in Durham, NC. Here’s reporter Harry Morrow of the Charlotte Observer on that captivating personality and its sunny side of life.]

“I always have a good day,” announces Wonderful Willie Sojourner, “only some days are better than others.”

Loose as a puppy and 6-feet-8 by 230 pounds, Sojourner is the life of the U.S. Olympic summer training camp at Duke University. “I came over to see what the masterminds eat,” he informs the coaches, and then Weber State’s star basketball player-high jumper-swimmer-horseshoe thrower-slot car racer-and free spirit regales everyone around with a few choice tidbits from the Life and Times of Willard Sojourner Out West.

He’s come a long way from Germantown, PA, and probably left people laughing all along the way to Weber State in Ogden, UT.

“I always wanted to be an Olympic swimmer, and I like horseshoes—that’s the only thing closeness counts in,” Sojourner continues, reeling in his listeners like fish. “I was the horseshoe champ at Weber State in intramurals. I went out there and beat those country boys!

“Nine out of 10 is nothing. Once I got started, I could ring all the time. It didn’t do me any good, so I’d ring one and ‘lean’ the other one.”

Sojourner surveys his audience, which is cracking up, and someone asks if he’s going to play football this fall. He says he wants to. “Coach wouldn’t let me last year because I might hurt my precious legs,” he says with mock concern.

Last winter, Sojourner did play a lot of basketball, though, averaging 22 points and 16 rebounds per game. “That’s because the coach only wanted 16 [rebounds],” explains Sojourner, a natural southpaw. “At the beginning of the season, he said we weren’t going to have too much rebounding. I said, ‘Is that all you want?’ He got disappointed. I’d get 16 and lay off. I shoot righthanded—it’s only fair to give them a chance.

“Long Beach beat us (in the NCAA tournament). They boxed me in, and the fellas wouldn’t shoot the ball. Their bench was better than our starting four.”

A 6-feet-6 high jumper in high school, Sojourner cleared 7 feet to tie for third in the NCAA meet last month after setting a Big Sky Conference record of 7-feet-1/2, his career best. “I could have gone higher,” Sojourner says—and you’ve just got to believe him—“but I got psyched out. I hit the base on my third attempt, but the bar flipped over and went down half an inch.

“I got mad and said to put it over 7 feet. I made it my first jump. I usually almost walk up to the bar. I’m hoping someday to do 8 feet,” he said with another laugh. “The day I made 7 feet, I said a brand-new door opened.”

Sojourner, who can still be more confident, might be an eight-foot high jumper one day. Or he might smash records in a swimming pool. Sojourner loves the water. When does he swim?

“Every chance I get,” Sojourner responds. “I’d rather swim before I play basketball, run track, or throw horseshoes. Everything interests me. I always find something new to do.”

Through the whole scene, one is aware that, even without any horseshoes, Sojourner is a ringer for Davidson’s Mike Maloy. He remains unconcerned. “I kind of remind me of me,” says Wonderful Willie Sojourner.

He’s quite a guy.

[Following up on that “quite a guy” and his quite a personality, next is an article on the 1974 playoff series between Sojourner’s New York Nets and his former Virginia Squires. The Nets are up three games to none, and Sojourner has his “three-games-is-enough” thoughts about the series. The byline belongs to the NY Daily News’ Jerry Cassidy, and his story ran on April 2, 1974.]

The Nets are talking sweep—four straight, that is, all except Willie Sojourner, who figures Virginia should concede after three straight.

“I’d like them out of it as soon as possible,” said Willie, who has a bad on for the Squires ever since coming here with Julius Erving for George Carter . . .

Fatty Taylor, Virginia’s scrappy guard, doesn’t see the Nets sweeping. He predicted, “We’ll win four of the next five.”

“I wouldn’t expect him to say anything different,” replied New York’s Brian Taylor. “If he conceded, he wouldn’t be a pro.”

Fatty also took exception to ex-teammate Willie Sojourner’s remarks. “You listen to Willie? You listen to him. Hey guys, does anyone listen to Willie Sojourner? Sojourner never knows what he’s talking about.” When told Willie predicted three wins and a concession, Fatty cooled down and laughed, “He said that? No comment.”

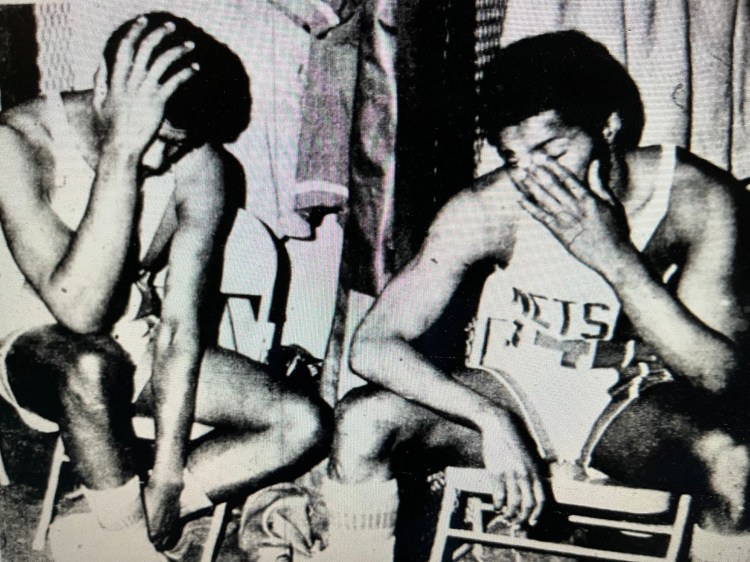

[Behind 31 inspired points from Sojourner’s former teammate Jumbo Jim Eakins, the Squires took game four to avoid the sweep. But the Nets buried the Squires in game five to take the series, four games to one. Though Sojourner was happy to be in New York, the trade moved him out from Jumbo Jim and put him behind The Whopper, Billy Paultz. Per usual, Sojourner’s playing time was limited, depending on the situation (Sojourner was known for going in and playing rough sometimes with St. Louis’ Marvin Barnes). But, as Tom Killackey of the Westchester Rockland pointed out earlier in the season, Sojourner, the undersized big man, usually made the most of his minutes. His article appeared on December 8, 1973 in The Standard-Star, New Rochelle, NY.]

It was a simple case of the bit player upstaging the stars in Friday night’s 138–102 New York Nets’ win over the Memphis Tams. Only Julius Erving and Billy Paultz scored more field goals than Nets reserve center Willie Sojourner during New York’s seventh-straight American Basketball Association victory—a club record—before 7,063 Nassau Coliseum fans.

Erving and Paultz scored 29 and 18 points respectively for New York, while Sojourner, one of eight Nets to hit for double figures, canned seven of nine field goal attempts for 14 points. While Dr. J and Paultz logged nearly three-quarters’ worth of playing time, Sojourner had to settle for a mere 18 minutes of action—roughly 15 more minutes than the 6-feet-8 center had been seeing in the first month of the season.

Apparently, rookie coach Kevin Loughery felt the Nets’ 98-79 lead at the start of the fourth quarter was sufficient to allow his bench a little exercise. Sojourner, who had popped in three of three chippies in a six-minute stint in the first half, responded to the added court time with four field goals, two blocked shots, and half a dozen rebounds in the final period.

Back at the start of the regular season, when the Nets players and coaching staff were talking ABA championship, Sojourner served as a sort of human oxygen mask—whenever Paultz needed a breather, Willie was there to fill the vacuum.

When the successful Nets preseason turned into the disastrous early, regular season, and Loughery started feeling a little like that NFL football coach up at the Yale Bowl, he decided on some changes. The Nets guards weren’t scoring, so Loughery paired John Williamson with Billy Taylor, relegating veterans Bill Melchionni and John Roche to the bench.

Erving, a surprisingly unselfish passer for a guy who averages 30 points a night, was solid at one forward, with rookie Larry Kenon a pleasant surprise at the other corner. Paultz, a hard-working, 6-feet-11, 240-pounder, was the incumbent center.

What to do about Sojourner?

“Everybody can’t play, of course,” admitted Sojourner after Friday’s game. “But I think I’m as good as anyone on this team.”

Against Memphis, Sojourner seemed better than everyone in the building, throttling Tams center Randy Denton and shutting off the middle against the other Memphis players. “We did a good job clogging up the middle tonight,” Sojourner agreed. “It was a good defensive effort, with everyone switching off at the right times.”

Sojourner’s nearest locker mate, Williamson, seconded his center’s appraisal. “We were too tight back in October,” smiled Williamson. “We played a tight man-to-man with hardly any switching off. The other teams picked us to death. If you let your man get by you, no one else would come up to help for fear of losing his own man. Now, we’re starting to get to know each other better. We help each other out.”

“People around the league are learning to respect our bench,” said Sojourner. “We’re proving you need a good bench to win consistently in pro ball.”

Can Sojourner beat out Paultz?

“Some people said Billy was the number one center on this team after Jim Chones left. Maybe he is. That doesn’t stop me from trying to win a starting job. Sitting on the bench is the toughest thing in the world for me. Every time a guy on the other team makes a move, my leg automatically kicks out like I’m trying to block a shot.”

Coach Loughery gave a more detached appraisal. “Willie has been tremendous in his last several appearances,” he said. “I never wanted to keep Paultz in for 40 or 45 minutes a game anyway. Now that Willie has shown what he can do, I’m not afraid to rest Billy more often.”

But can he start?

“Every good athlete feels he should be playing more,” answered Loughery. “Billy was the holdover from last year. It was his job to lose in the preseason. I would have started Sojourner over Paultz if he had outplayed him, but it didn’t work out that way.”

He’s not a star yet, but Willie Sojourner will be making more than cameo appearances as winter progresses. He’s just the insurance Central Casting ordered if the Nets hope to come up with a hit this season.