[From Way Downtown highlights 20th century pro basketball players and the journalists who covered them. In that spirit, here is a tribute to Wilt Chamberlain soon after his passing from journalist, David DuPree, always a good read. DuPree’s thoughts, published in late 1999 in Hoop Magazine, got me thinking about the late Frank Deford’s recollections of Wilt in his latter years. Deford wrote:

It struck me almost immediately, how content [Wilt] was now. When he was playing, he had often said that his happiest year has been the one when he had traveled with the Harlem Globetrotters before he joined the NBA. Now, he was even more at peace. In fact, I’m not sure that there’s ever been a great athlete, besides Wilt, who was so uncomfortable when playing and then was so much happier retired.

Deford wasn’t the only one to say this. I once talked a retired sportswriter from L.A. who shared the following story, which I’m paraphrasing. In 1996, the former reporter was out and about one day when he bumped into Wilt riding his bicycle at a Southern California beach. They stopped to chat and, while reminiscing about the old days, a young kid hustled over. The kid stood there, eyed Wilt and his hulking frame, then mustered the words, “Are you Shaquille O’Neil?” (Shaq had just signed with the Lakers.) According to the reporter, Wilt chuckled and told the kid that he was. As the reporter explained, Wilt didn’t care anymore about his notoriety. He was at peace out the limelight, where he could be himself, not have to live up (or down) to his public persona.

DuPree doesn’t go into Wilt’s peaceful, easy feeling. But he captures well just how amazing “The Dipper” was.]

****

I have Wilt Chamberlain’s autograph on an old, crinkly piece of paper. It’s 40 years old, in fact. It’s faded a bit because I never kept it under glass or tried to preserve it in any way. I got it when I was 12 years old, and I put it in a box and kept it with a lot of other things from my childhood, like a yo-yo, some jacks, some dice, and an assortment of not-in-mint condition baseball cards and some old electric football men.

I never thought about it, although the box did come with me wherever my life took me. When Wilt Chamberlain died on October 12, 1999, I thought of the autograph for the first time in probably 40 years. I didn’t think how much it would be worth or anything like that. I just thought that I had something that Wilt touched, and it was chilling.

I’m a Michael Jordan man. I covered him his entire career, and I think he was the epitome of a basketball player. He was the best I have ever seen once I started understanding what I was looking for. But Chamberlain was special. For much of my career as a sportswriter, Jordan was the game of basketball. Chamberlain was above it.

I have some autographed basketballs and autographed books and things like that, but Chamberlain’s is the only autograph I have that’s on a seemingly harmless piece of notebook paper ripped out of a three-ring binder.

As I sat and thought about Chamberlain when I heard of his death, that day back in 1959 when I got his autograph crystallized in my mind as if it was yesterday. I can’t remember anything else that happened that long ago so clearly. Chamberlain was playing for the Harlem Globetrotters at the time, and a friend of my father was a friend of Chamberlain’s father. So, when the Globetrotters came to Seattle (pre-SuperSonics days), I got invited to the game and a chance to meet him.

I expected him to be as big as a skyscraper, but when I saw him in person, it was kind of a letdown. It wasn’t Wilt’s fault, but anything short of a skyscraper would have been a let down because that’s how big Chamberlain was in my 12-year-old mind. But once I saw him play, it didn’t matter. Even though it was the Globetrotters and I knew little about what greatness really was, I knew that Chamberlain was a special athlete.

I got to see him after the game to get his autograph, and he addressed me as “young man,” not “little fellow” or “son,” but “young man.” It made me proud, and I followed his career religiously ever since. I always rooted for him against Bill Russell, and I wanted to be Wilt Chamberlain when I grew up.

Chamberlain, considered by many to be not only the greatest basketball player ever but the greatest athlete period, took that marvelous ability and tremendous size, 7-feet-1, 275 pounds, and made the most of it.

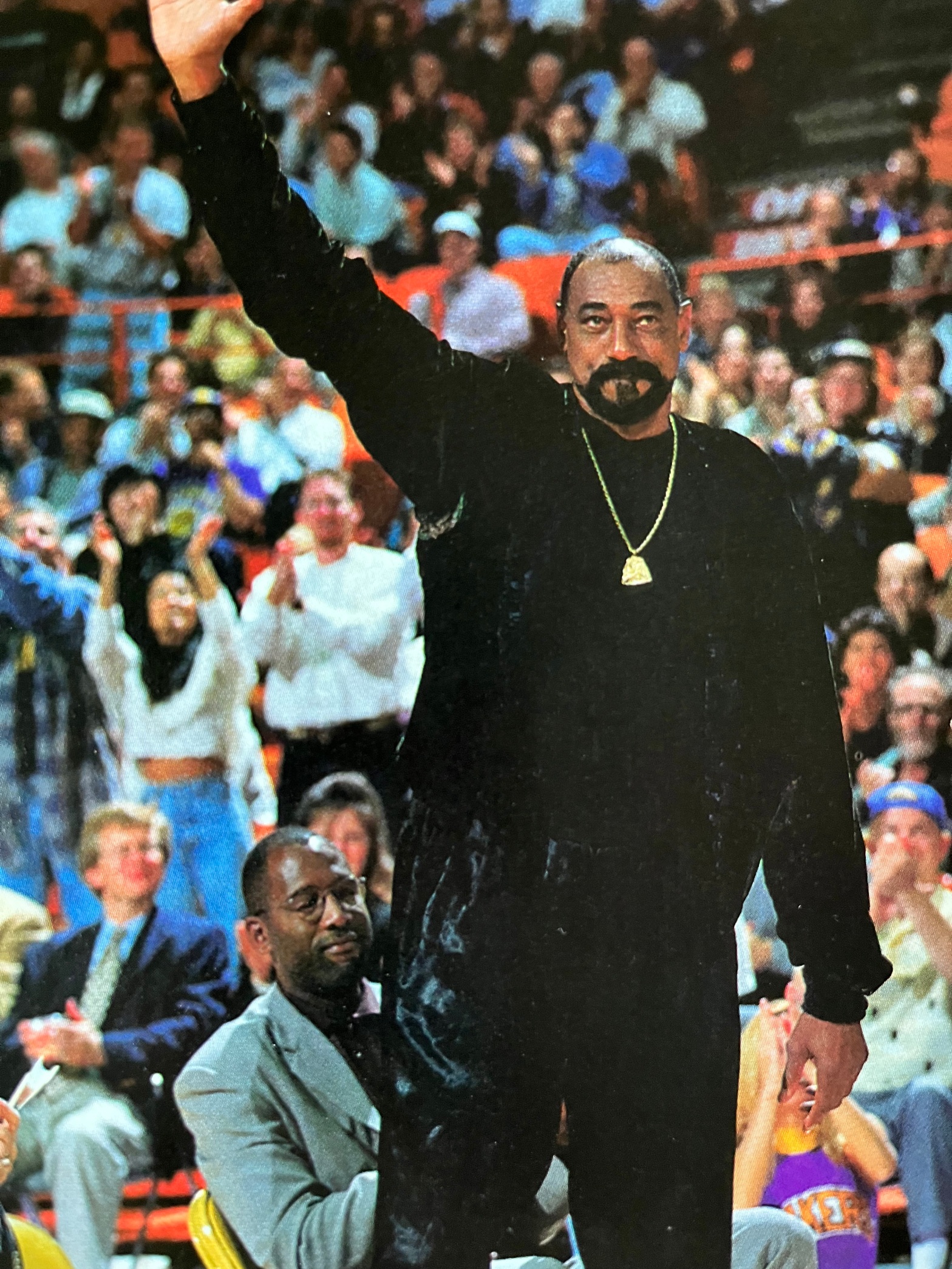

“I think that my legacy should be that I gave credence that you could be big, bigger than most, and still have athletic ability,” Chamberlain said a couple of years ago when the NBA was celebrating its 50th anniversary season.

He was the most-dominant player in the NBA from the first day he stepped on the court. He had 43 points and 28 rebounds in his first game and went on to lead the league in scoring (37.6 points per game) and rebounding (27.0) and became the first of only two players to win the MVP and Rookie of the Year in the same season. (Wes Unseld was the other.)

His NBA accomplishments are so remarkable, it almost is irreverent to compare him to anyone—even Jordan. He not only is the sole player in NBA history to score 100 points in a game, but he also has the three highest scoring games in NBA history, and 15 of the top 20 performances. He averaged 50.4 points a game one season and 44.8 in another.

For his 14-year career, Chamberlain, 63 at the time of his death, averaged 30.1 points and 22.9 rebounds and retired after the 1972-73 season. He’s also the only player ever to have more than 20 points, 20 rebounds, and 20 assists in the same game.

Chamberlain is second on the NBA’s all-time scoring list with 31,419 points, 6,968 points behind leader Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who played six more seasons than he did. [Editor’s note: Chamberlain, of course, is now number three on the list behind Lebron James and Abdul-Jabbar.] He led the NBA in field goal percentage nine times, in rebounding 11 times, and in scoring seven times. He even led the league in assists one year, just to prove he was more than a scoring machine.

Chamberlain and Boston Celtics star Bill Russell had one of the most heated and intense rivalries in any sport. Chamberlain was the unstoppable offensive force, and Russell was the greatest defender ever. Chamberlain may have been the next best defensive player, too. They didn’t start recording blocked shots until the 1973-74 season, the season following Chamberlain’s retirement.

He once said he came into the NBA as a defensive player. “Everyone was afraid of my defensive game more so than my scoring game,” he said. “Scoring was a secondary thing, but it was also very natural to me.”

Jordan may have been the ultimate product of the evolution of the way the game of basketball is played today, following in the footsteps of Elgin Baylor, Connie Hawkins, Julius Erving. But Chamberlain was so far ahead of his time that they still haven’t caught up.

He was almost mythological, and they changed the rules to try to give opponents a better chance to offset his dominance. Chamberlain had remarkable quickness and might’ve been the strongest player ever.

One of the statistics that may tell more about Chamberlain than any other was one that has nothing to do with scoring or rebounding. It had to do with just being there. In his third season in the league, he averaged 48.5 minutes. The extra half-minute was because of overtime games. He missed only eight out of a possible 3,890 minutes. Chamberlain wanted to leave the impression on every opponent that he was there from beginning to end, he wasn’t going anywhere, no matter the score, and you always had to go through him to get any place you wanted to go. Remarkably, for all the time he spent on the court, he never fouled out of a game.

But to judge Chamberlain only by his incredible NBA statistics is to miss the boat on the effect he had on sports in general and on just how great an athlete he was. He could also run a 40-yard dash in 4.4 seconds, had a 50-inch vertical jump, was a Big Eight high jump champion at Kansas, was undefeated in the shot put. But his best track event might have been the 440-yard dash. His first athletic dream was competing in the Olympics in the decathlon. He almost fought Muhammad Ali, and former Kansas City chiefs coach Hank Stram tried to talk him into playing football for him.

Chamberlain was also saddled with a number of nicknames. He didn’t like “Goliath” and “Wilt the Stilt,” but “The Big Dipper,” he did like, especially when shortened to “Dipper.”

His long-time friend Meadowlark Lemon, who referred to Chamberlain as “Dippy,” spoke at Chamberlain’s memorial service and captured Chamberlain’s life in simple terms: “In Wilt’s life, there were no sad songs. He lived his life to the fullest.”

Russell, whose deep friendship with Chamberlain was unknown to most for many years because of their intense battles on the court, looked at Chamberlain as his brother, someone he loved. “I knew how good he was, and he knew that I knew how good he was,” said Russell. “I’ll just say that as far as I’m concerned, he and I will be friends through eternity.”

Chamberlain loved to travel and had a wide variety of interests that went beyond sports. He co-starred with Arnold Schwarzenegger in the movie Conan the Barbarian, and he was taking saxophone lessons and working on a screenplay about his life story when he died.

“He was interested in everything,” his long-time friend and attorney Sy Goldberg said. “He was truly a man for all seasons.”

By the way, I can’t find the box that has Chamberlain’s autograph in it. I’ve looked everywhere, but I’ll keep looking. I know it’s someplace. It really doesn’t matter that I don’t know where it is because I know I did have it once—just like we all had Wilt—and the memory is everlasting.