[No intro needed for Slick Watts. One thing, though. In the 1970s, Watts had that jaunty look and that huge personality. It was easy for big-city reporters to broad-brush him as simple, downhome country folk. I talked with Watts for my Archie Clark book, granted decades later, and he was anything but a loudmouth or a simpleton. Not only was Watts a good interview, he was quick, perceptive, well-spoken, and candid. In short, a great guy.

So, this article pains me just a teeny-bit for its broad-brushing of Watts in a few places. But I put up these print articles to help digitize pro basketball’s past and keep its legacy alive. Obviously, Watts is one of the good ones to remember. At the typewriter is none other than the New York Times’ Sam Goldaper, Mr. Prolific himself, and his article appeared in the magazine Pro Basketball Extra, 1976-77. One last thing. Watts suffered a major stroke in April 2021. Here’s wishing he and his family the very, very best on his continued road to recovery. ]

****

“The key word is submit, and until I have players that are willing to submit to the team in whatever role they are asked to serve, you won’t have a consistent winner. It comes down to just how much each man is willing to sacrifice his ego for the benefit of his team. That was the credo the Boston Celtics lived and still live by. It translates into winning.

—Bill Russell

This is the story of one such player. During the 1973-74 season, Bill Russell’s first as the Seattle SuperSonics’ general manager, coach, housecleaner, and joker, a small backcourt man, his head clean shaven because of medical problems, began appearing in the lineup.

The first time he played at Madison Square Garden, the public-address announcer John Condon said, “Into the game for the Seattle SuperSonics, number 13, Don Knotts.”

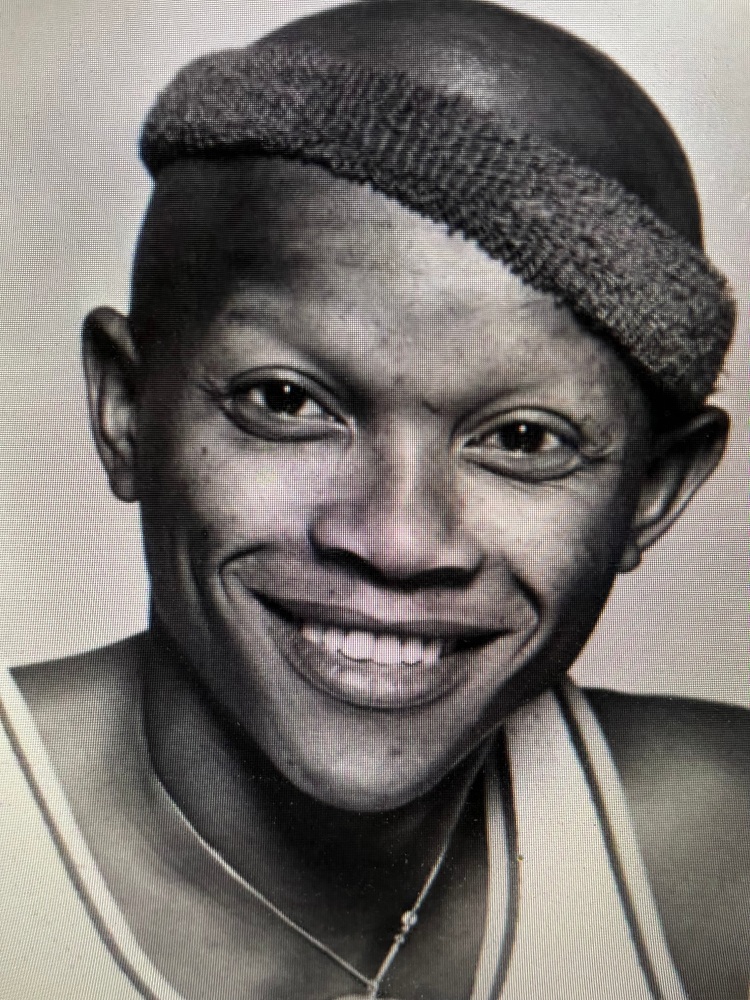

Condon was thinking of the television comedian, rather than Donald Earl (Slick) Watts, the quick guard whose trademark is a sweatband that is tilted at a rakish, comic angle on his shiny pate.

Everybody loves to cheer for the underdog—you know, the longshot that the pro scouts overlook in their annual travels each season, hoping and seeking the sleeper who will become a star. Watts, not a college basketball household name, is the overlooked, unheralded player who has gone from a walk-in at the Sonic training camp to one of the NBA’s outstanding penetrating guards.

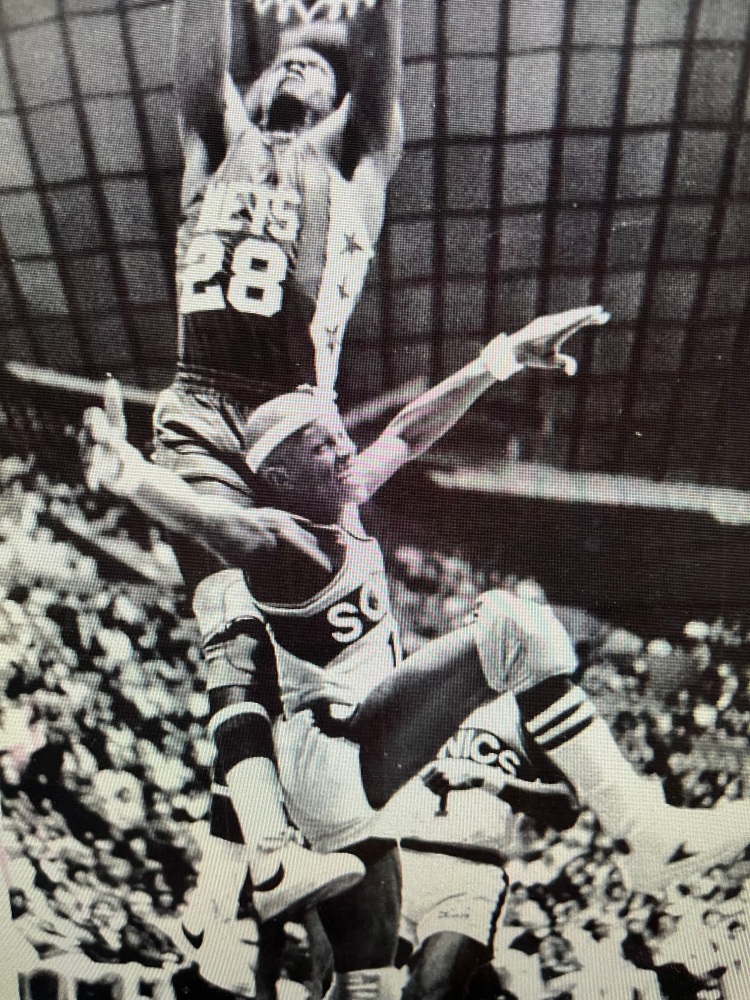

Watts is pro basketball’s premier “thief” and one of the most-popular players with the fans. The 6-feet, 168-pound Watts led the NBA with 261 steals and 661 assists, indicating his value at both ends of the court.

Even though Watts is in his fourth pro season, people around the league are still finding it difficult to come up with adjectives to describe his unusual style of play. They laugh when he darts, intercepts, and makes improbable passes. Somehow, they still wonder how his bent-over, baseball-throw shots get into the hoop, especially in the clutch. During Watts’ act, he always has a wide grin that exudes confidence.

“Slick is a good player, a great one for us,” said Russell. “I said when he first came that the one thing that could help us more than his improvement as a player would be for his enthusiasm to become contagious. It has. The chemistry of this team is excellent, like the old Celtics. And it is Slick Watts who does the most to keep it that way.”

Everything about Watts has a fairytale aura, even his hometown of Rolling Fork, Miss., whose last population count was 2,034. Until Rolling Fork exported Slick Watts to the outside world, its greatest fame lay in its designation as county seat of Sharkey County, a vast territory encompassing 436 square miles.

“It’s near Panther Burn, which is near Onward, which is near Jackson,” said Watts with an omnipresent grin.

In high school, when Watts was averaging “about 36 points” a game by his own count, he says he was a pretty fair player. In explaining his bald scalp, which has become his trademark, Watts tells the story about the time he was little and had his head shaved in a style that was popular in the South during the 1960s.

When he was 13 years old, a freak football injury caused a scalp wound that never healed properly. His hair started growing in weird patches. He took the practical way out and shaved his entire scalp. The shaven head prompted nicknames of Mop Head and Shine in his high school days. When he enrolled at Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans, some inspired sophisticate started to call him Slick, and soon Donald Earl was all that forgotten.

Before Watts arrived at Xavier, there were stopovers at Drake University in Des Moines and Grand View Junior College, a small school affiliated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church also in Des Moines. “I waited three weeks before shipping out of Drake,” remembers Watts. “There was some trouble with my college entrance boards. They were supposed to be high enough to allow me to play basketball. But after three weeks, they changed their minds, so I left.”

At Grand View, Watts switched his uniform number from 13 to 22, averaging 28 points a game and maintained a B average that allowed him to enroll at Xavier. There he studied physical therapy and played basketball well enough to average 17 points during his senior year. He also led the team in assists (11 per game) and steals (8 per game) and was named to the NAIA second-team All-America.

Throughout his college career, his dream was to become a pro basketball player. The dream would have failed were it not for the help of Bob Hopkins, his college coach, who just happens to be Bill Russell’s cousin and is now Russell’s assistant. During the NBA and ABA college drafts, Watts’ name went unmentioned through all 10 rounds. “I was hurt,” recalled Watts. “I began to think the pros were not aware of me.”

Hopkins had convinced the ABA’s then-Memphis team to add Watts’ name to their supplementary draft list. But to add further insult to Slick’s disappointment, they never even invited him to training camp.

When Hopkins teamed with Russell, the Sonics were a team of fat cats, big reputations, and huge salaries. Seattle had never made it to the playoffs since entering the NBA as a 1967-68 expansion club, even though owner Sam Schulman spent big money to acquire some of the biggest names in college basketball. But sometimes big names and reputations don’t go together on a basketball court. Russell has changed that, and the Sonics have now made the playoffs the last two seasons.

Watts was invited to the August 1973 camp where Russell and Hopkins gathered 35 unknowns. “I didn’t know a lot about him,” said Russell. “His only credentials were that Hop had sent him and told me that he could play. I did know that he was about the funniest-looking basketball player I had ever seen.”

Watts’ quick hands, desire, dedication, hustle, and showmanship quickly made him a crowd-pleaser. But even after Russell signed him to the $19,000 minimum contract, the Sonic coach said: “I don’t know why I kept him.”

Later, Watts was to say: “I would have played for $1 a day just to prove myself.”

Six weeks into his rookie NBA season, Watts proved his worth. While the Sonics struggled with a 9-17 won-lost record, Watts had averaged nine seconds of playing time a game. “Every day, I would tell Russ I was ready,” Watts said looking back on that rookie season, “and every day he would say, ‘Sit down, Slick.’”

On December 1, Watts got the chance that he had long dreamed of. Russell sent him in against the Atlanta Hawks on a whim, and he responded with 21 points and four assists. The next night against the Washington Bullets, he collected 24 points, grabbed 11 rebounds, had six assists, two steals, and a blocked shot.

During the 1974-75 season, playing as the Sonics’ third backcourt man, Watts was seventh in the league in assists, fourth in steals, and averaged 6.8 points. As a starter in the Sonics’ first taste of the playoffs, Watts averaged 11 points and seven assists. And while the Sonics were being eliminated in the Western Conference semifinal round by the Golden State Warriors, Slick played all 48 minutes, had 24 points, 11 assists, and four steals.

With the start of the 1975-76 season, Watts signed a new contract, which he said put him “near the six-figure mark.” It contains an unusual clause that if the Seattle management at any time felt that his play didn’t merit the raise, it could refuse to pay part of his salary. “I don’t want money for nothing,” said Watts. “I just want to work for it.”

In response to a question that he could possibly get into such a slump that the Sonics might exercise that clause, Watts confidently said: “All my life, I have gone through the agony of having to prove myself. I don’t think I will ever be in a slump. A lot of guys try to shoot their way into pro basketball. I don’t. I work hard, hustle, and play defense. All I need to do is stay healthy.”

Fast is what Watts is all about. Few players can change the tempo of a game the way he can. “All my life, I was told I was too small to play basketball. Now, I’m glad I’m quick instead of big,” said Watts. “Speed works better than size. I feel that if I can beat them there, I can do what I want before they get there. Because I think I have the quickest hands in the West, I sometimes stand up before a mirror and flick at myself to see how quick I am, and sometimes I have a tough time keeping up with myself.

“I just try to go where the ball is at all times. I’m a gambler. Because of my quickness, I can cover a lot of ground.”

Watts’ arms could cover a lot of ground just by themselves. He has 37-inch sleeves and doesn’t think there is anybody in the NBA that he can’t steal the ball from or set up for a steal. When he’s not on a roadtrip or executing his blindside, over-the-elbow steal, the gregarious Watts is the Sonics’ No. 1 goodwill ambassador. He makes numerous appearances at hospitals and schools.

He always seems to be surrounded by kids, clamoring for a headband or an autograph. “I guess fans relate to me because I’m unique and different,” says Watts. “They know I’m sincere in my smile. For me, it’s a privilege when they ask for my autograph. I guess I relate to people just naturally. A lot of people say to me, ‘Slick Watts, I really appreciated the way you treated my kids.’ During my speaking engagements, I talk about desire, hustle, dedication, and the things that got me into the pros.”

Bob Walsh, the Sonics’ assistant general manager, is one of the biggest fans of Watts. He says he has never met a person with Slick’s public-relations power and magnetism. “He’s mystical,” said Walsh. “Slick is the one guy I know who can make you believe anything he says. I remember when he was filming a television commercial, and the director asked him how someone of his size could play against all those giants.

“With a straight face, Slick responded: ‘In anatomy, I learned that it takes less time for a message to get from the brain to the feet of a little man than it does with a big man. So, when I decide to move, my feet know it way before his do.’ You know something, for a few seconds, that man believed him.”

Watts’ charisma spilled over to the Professional Basketball Writers Association of America. The group voted him its annual Citizenship Award, given to the player, coach, or assistant coach adjudged to have performed outstanding and humanitarian achievements within the community.

In accepting the award, Watts said: “Giving pleasure is the greatest thing a person can do in life. I am part of this community, and it is a beautiful place. God picked it out just for me and said, ‘Slick, I’ve got this little heaven for you. I call it Seattle.’”

Watts also remembers the Lord and His Commandments. The eighth one says, “Thou shalt not steal.” To which Watts replies: “Except on defense.”