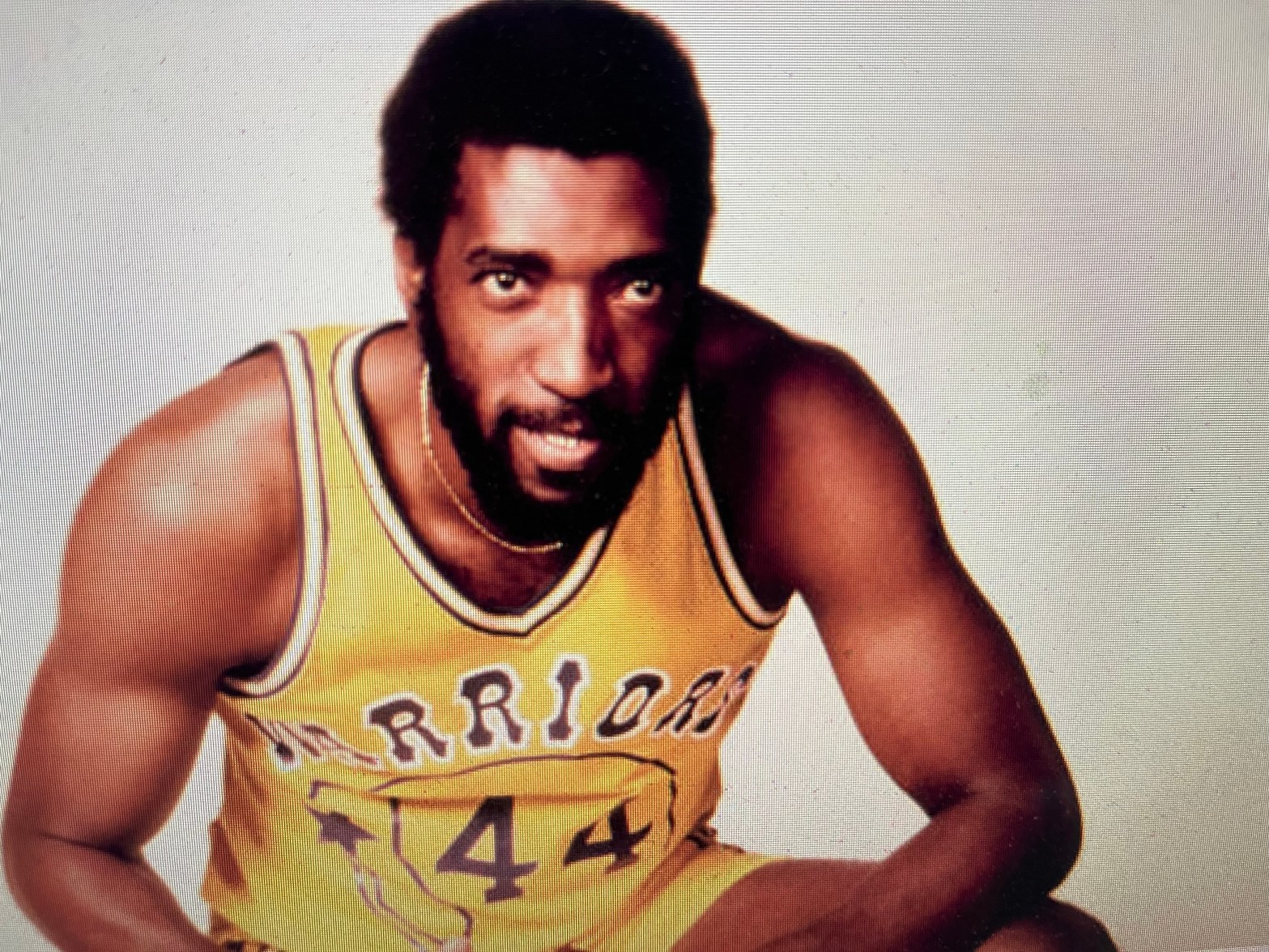

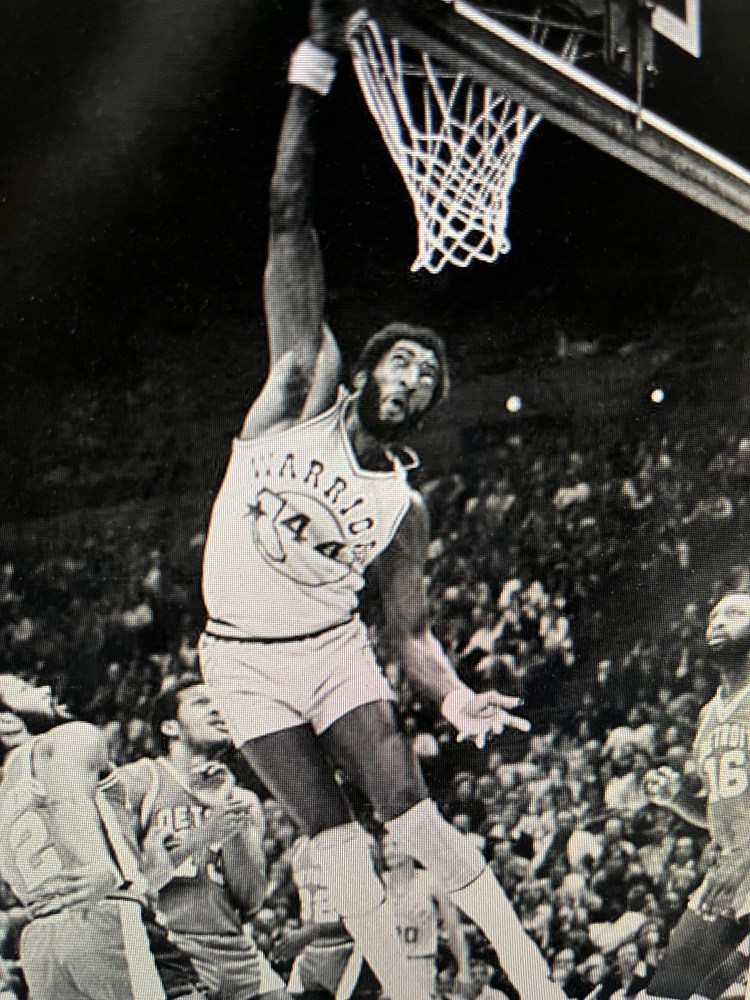

[Clifford Ray was once described as “a Wildman with a clarinet.” A 6-feet-9, 235-pound Sidney Bechet. Ray also was a Wildman on the basketball court for the Golden State Warriors (1974-81). He did all the dirty work inside, occasionally popping outside to the perimeter to wave the basketball around like a kumquat in his giant right hand and always revving up the crowd a time or two each game with rim-rattling dunks.

Here’s a brief article about Ray joining Golden State. Or, more precisely, Ray came to Golden State in a trade that sent the ailing Nate Thurmond to Chicago. Not an easy ask to replace Thurmond, one of the all-time greats and beloved in the Bay Area. But Ray managed it, helping the Warriors to an NBA championship in 1975. This article, published in the February 13, 1975 issue of Basketball Weekly, comes from the Detroit-based journalist Mark Engel.]

****

As the Golden State Warriors assembled around one basket in Detroit’s Cobo Arena, taking practice shots as is the pregame custom, Clifford Ray was flopping on the floor near midcourt. He looked like a giant contortionist, stretching the legs that would carry him 37 minutes this night against Bob Lanier, and countless more through the end of a long season.

It was the last thing, however, that Clifford Ray would do without his teammates. Their union is actually a recent one, with Golden State having for so many years called Nate Thurmond its center. He is now gone, dispatched to Chicago in exchange for Ray in a deal interspersed with dollars and draft choices. While young George Johnson is there to play fireman, it is Ray who starts every game. In essence, it is Ray who the fans view as Nate’s replacement.

Ray knows the role that he stepped into, and he relishes it. “I realized I was going into a situation where the guy was an institution,” Ray started. “Nate was a Bay Area hero just like Rick Barry still is. But I’ve always felt I’ve had a rough time all my life. I may not have the ability of some others, but I always work hard.”

And that, quite simply, is Clifford Ray, a man whose play in not always understood by casual observers, a man whose seeming indifference to these Dollar Days is unique. And he is a man who stands in basketball’s hazy areas, overshadowed by more publicized teammates throughout his career due to a lack of impressive statistics. But his approach to it all is certainly refreshing.

He came out of Oklahoma four years ago, drafted third by the Bulls, and unknown to all but the most studious fans and some pro scouts. His anonymity failed to stop him from making the league’s All-Rookie team, however, the only member of the first unit not picked on the draft’s initial round. The Bulls made the playoffs that season, as they did all three years Ray was on the team, but never did they make it as far as the finals.

A reason was needed, and conveniently Chicago—with a team of high-scoring forwards and guards with a penchant for gaining attention—had its center to point that finger at. “People said if you don’t win, it’s because you don’t have a dominating center, and I was always the scapegoat in Chicago,” Ray stated. But he wonders, while recalling Boston’s playoff crown, how much Dave Cowens ever dominated a game.

Were it not for an injured leg—now scarred on both sides after eight hours of surgery two years ago—Ray this day might be a Philadelphia 76er. He was offered in a trade when the Bulls coveted a local collegian, Doug Collins, and the Sixers might have made the rookie available but weren’t willing to gamble on the 6-feet-9 Ray’s health. Ray believes it’s all part of the game.

He takes to heart the advice of friends on the Bulls: There’s always going to be a place for somebody who does his job well.

“I’ve always carried that philosophy,” Ray noted. “And if Wilt (Chamberlain) can be traded, anybody can be traded. He’s the greatest thing in basketball ever. That’s why I don’t worry about it.

“There’s no problem in adjusting to a thing like that. You should enjoy playing basketball anywhere.”

From Day One on the Warriors, the new center was made to feel at home. “It’s a different type of experience,” he said. “I can’t compare it with all the clubs, since I’ve only been on just the two, but it’s a tremendous philosophy. The guys pull together as a team. I’m really happy—and you’ve got to enjoy the work you do.

“It’s handled a lot better here,” he added. “We lose as a team; we win as a team. This is the philosophy handed down by Coach Attles. It’s paying off when you don’t have to worry about dissention and ego-tripping.”

And unlike in Chicago, where the center is called on for few offensive tasks other than setting screens and rebounding, Ray was greeted in California with a few plays designed to get him the ball. That, too, is part of the Attles’ philosophy.

“You ought to have something specific for every player on the team, even if you don’t call those plays a lot. It’s all predicated on compatibility for the team. We try to keep everybody happy,” Attles stated. “Cliff we don’t need to score that much. He concentrates more on setting picks and playing defense, and not too much on shooting. But his most-important factor is that he wants to contribute whatever he can to winning.

But people insist on asking the personable young man: Why don’t you shoot the ball more? Ray replies that these people don’t always understand the game. “If I use the ball, I’m taking away from the other guy’s job,” Ray stated. “I never solo off on my own. I don’t believe in that. For a team player, you take the role that’s given to you.”

And so, while the scoring ability is there—as proven by past playoff performances—he is content to accept an average of 8.8 points per game with just under 11 rebounds. He can score when the Warriors need a lift, and in the meantime, provides the aggressive play this team cried for in the past.

“I’m very competitive,” Ray said. “I’m easy going normally, but when I play basketball, it’s sorta like I let out all my frustrations. When I’m playing, I’m a mean guy. I think I have to be.

“Our team is like that. All our guys are super nice guys. Coach Attles says we have to get tough so we won’t get pushed around. I admire guys who play rough, as long as they’re not dirty.”

And through it all, Ray seeks one thing—respect—from his coach, from his teammates. And surely, from himself. “If you’re your own worst critic,” he feels, “you’ll always be all right.”