[By the late 1930s, the pro basketball season came with a few highly anticipated frills. One was the annual showdown between the winner of the Chicago-based national pro tournament, usually a National Basketball League (NBL) squad, and a picked team of the nation’s finest college all-stars.

In 1949, the NBL merged with the rival Basketball Association of America (BAA) to form today’s NBA, and that brought the annual pro tournament to a screeching halt. The BAA contingent thought the tournament was a rotten idea, setting up a scenario in which a non-NBA team won the whole kit and caboodle and belittled their league. But the BAA folks agreed to keep the pro vs. college showdown alive. The game, sponsored by the Chicago Herald-American, generated lots of free publicity, and if the collegians won the game, a few young stars would be born that the NBA could promote the following season as promising rookies.

The Chicago Herald-American had plenty to say about the annual college-pro showdown. But I don’t have access to the newspaper’s archives. The next-best source is the oversized Converse Basketball Yearbooks that many of us flipped through as kids. The following article, written by the Herald-American’s Jim Enright, appeared in the 1950 edition. By the way, Enright was a top basketball referee for more than 30 years, also serving as the designated whistle on several Harlem Globetrotter world tours. Take it away, Jim.]

****

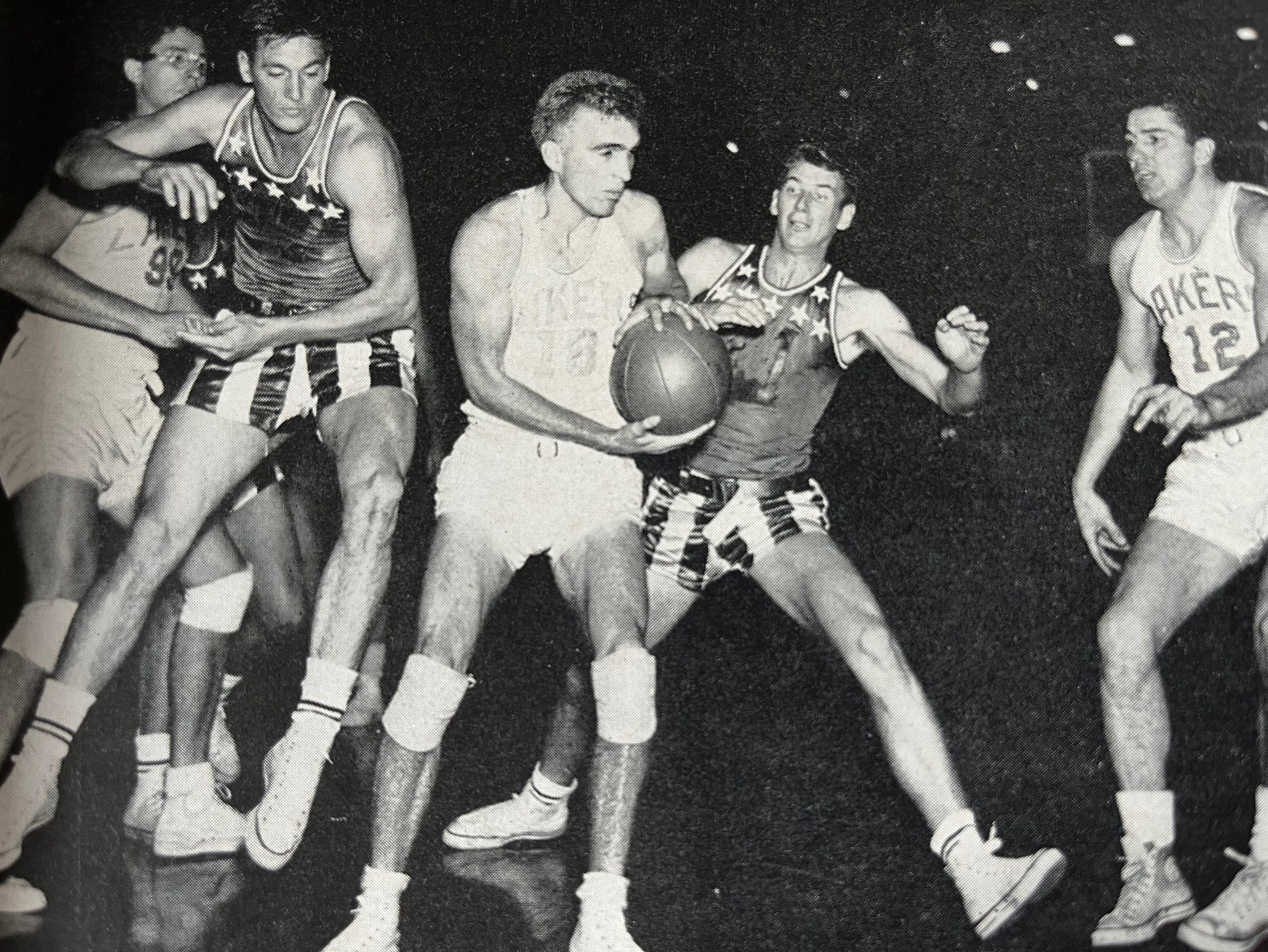

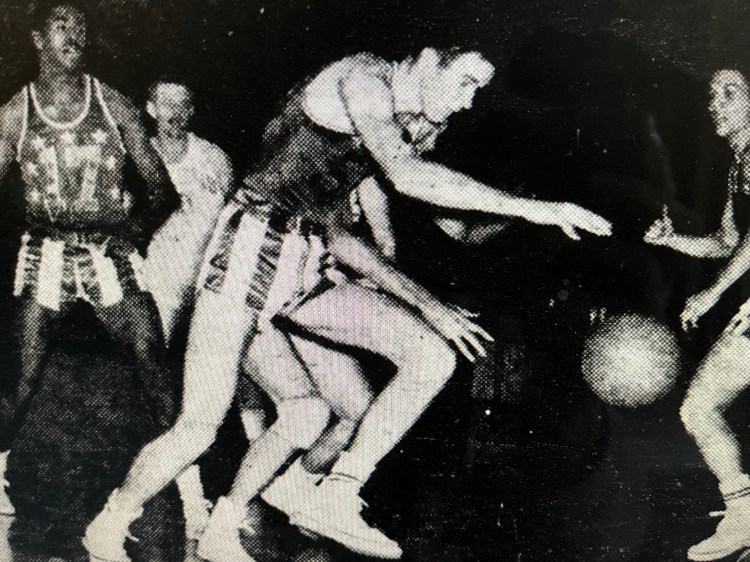

They wrote the script for last season’s professional basketball’s Who’s Who on the night of October 26, 1949 in the Chicago Stadium. Just before the midnight witching hour of that October evening, the Minneapolis Lakers won another basketball game that left very few questions regarding cash-register bounce ball unanswered.

This conclusive contest was the Minneapolis team’s 94-86 outpointing of the 1949 College All-Star team in basketball’s biggest game, sponsored by The Chicago Herald-American for that newspaper’s benefit fund.

The fact that six months later, the Lakers were crowned champions of the National Basketball Association was hardly a surprise to any of the 16,731 folks who watched the fact-finding evidence unfolded during the progress of the 10th annual All-Star classic.

The 1949 squad was one of the greatest ever assembled. It was assured a maximum of team play since Kentucky furnished four members of its NCAA championship cast of the previous season, plus its colorful, capable coach—Adolph Rupp.

Despite these factors, the Lakers did everything but outscore the All-Stars in the field-goal column in recording the professionals’ fourth win in 10 of these annual stands against the graduating cream of the intercollegiate crop.

After this performance, it was just a matter of playing out the schedule to decide who the Lakers were going to play to wind up with all the professional basketball marbles. In due time—after the opening of the 1950 major-league baseball season—even this fact rang true as Minneapolis won four of six games against the boys from Syracuse to gain the title they were figured to capture after that winning performance in October.

If the Lakers aren’t the best team in all professional basketball history, they’ll do until somebody revives the Original Celtics, the pre-war Fort Wayne Zollner Pistons, or gives the Harlem Globetrotters enough experienced height to cope with the Ben Berger-Max Winter wizards.

Big George Mikan was never greater in this All-Star classic—and he’s played on both sides. If ol’ No. 99 needed any prestige or votes to clinch winning the Associated Press poll as basketball’s top player for the first half of the century, he locked ‘em up October 26, 1949, Rupp and his associate coaches—Tom Haggarty, who has since switched from Loyola of Chicago to Loyola of New Orleans, and Eddie Hickey, the little professor of basketball success at St. Louis University—attempted to apply all the old defenses and some of the new ones on the amazing wonder from Joliet, Ill., but without success.

Mikan was the only Laker that the Rupp-ized coaching colony didn’t stop—and big George proved the difference in the Lakers victory. Finishing a shade stronger than he started, Mikan tossed 31 points with 11 field goals and nine-of-14 free-throw chances.

Outside of a brief second half pause to refresh, Mikan played right down to the closing seconds before drawing his sixth and exiting personal foul. It was lucky for the Lakers that Mikan was available for this final spurt, because the All-Stars challenged right down to the wire.

As it turned out after the sensational finish furnished by these All-Stars, who asked for nothing and gave plenty, the Mikan-ized start and finish supplied Minneapolis with its eight-point advantage at the windup.

Eight points was exactly the spread of the Laker edge after the first quarter, as Minneapolis shot for 30 of the 52 points registered in the kickoff session. Thereafter, the 49-42 bulge at halftime and the 73–63 edge after the third quarter were also in the Lakers’ favor.

The All-Stars “won” the final quarter via a 23-21 edge as Minneapolis and Mikan retained the eight-point advantage gained in the first quarter.

As a fitting tribute to the sensational, action and thrills, the two teams ended up writing five new marks into the classic record book, namely:

- Mikan’s 31 points exceeded Bobby McDermott’s 24 in 1946.

- Wah Wah Jones’ 22 points gave him the All-Star high-scoring mark that was set by Jim Pollard with 19 in 1947.

- The two-team total of 180 points was an even 50 better than the combined former record set by Indianapolis and the All-Stars in 1947.

- Mikan’s 11 field goals eclipsed McDermott’s record of eight set in 1944.

- Jones collared nine field goals to exceed the previous collegiate mark of eight set by Pollard in 1947.

The 16 All-Stars were selected by the Herald-American sports department headed by Leo Fischer. Tony Lavelli was the only player who didn’t get into the game due to a last-minute decision by the American Amateur Union to attempt to protect his amateur status. As a result, Tony soon after exchanged his basketball and accordion musical talents for a Boston Celtics paycheck. The entire show was quarterbacked like a real major by Clyde Stafford of the Herald-American promotion department.