[What follows is a brief feature on Calvin Murphy that appeared in the December 1974 issue of Hoop Magazine. The feature’s original headline read: The Little Rocket Who Could. But I want to tilt this story in a slightly different direction. Not only did “the Little Rocket” help in the 1970s to open up the NBA’s backcourts to “the little man,” he did so under three different head coaches in his first four seasons. Murphy had to step up for each head coach and prove himself anew as NBA worthy. Because he (referring to his extreme will and talent) “Could” get the job done, Murphy just kept rising as a pro and proving his critics wrong. The Houston Post’s Tommy Bonk tells the story, which is mainly of historical interest for Murphy’s long quotes on how he fought the tall odds against him and won.]

****

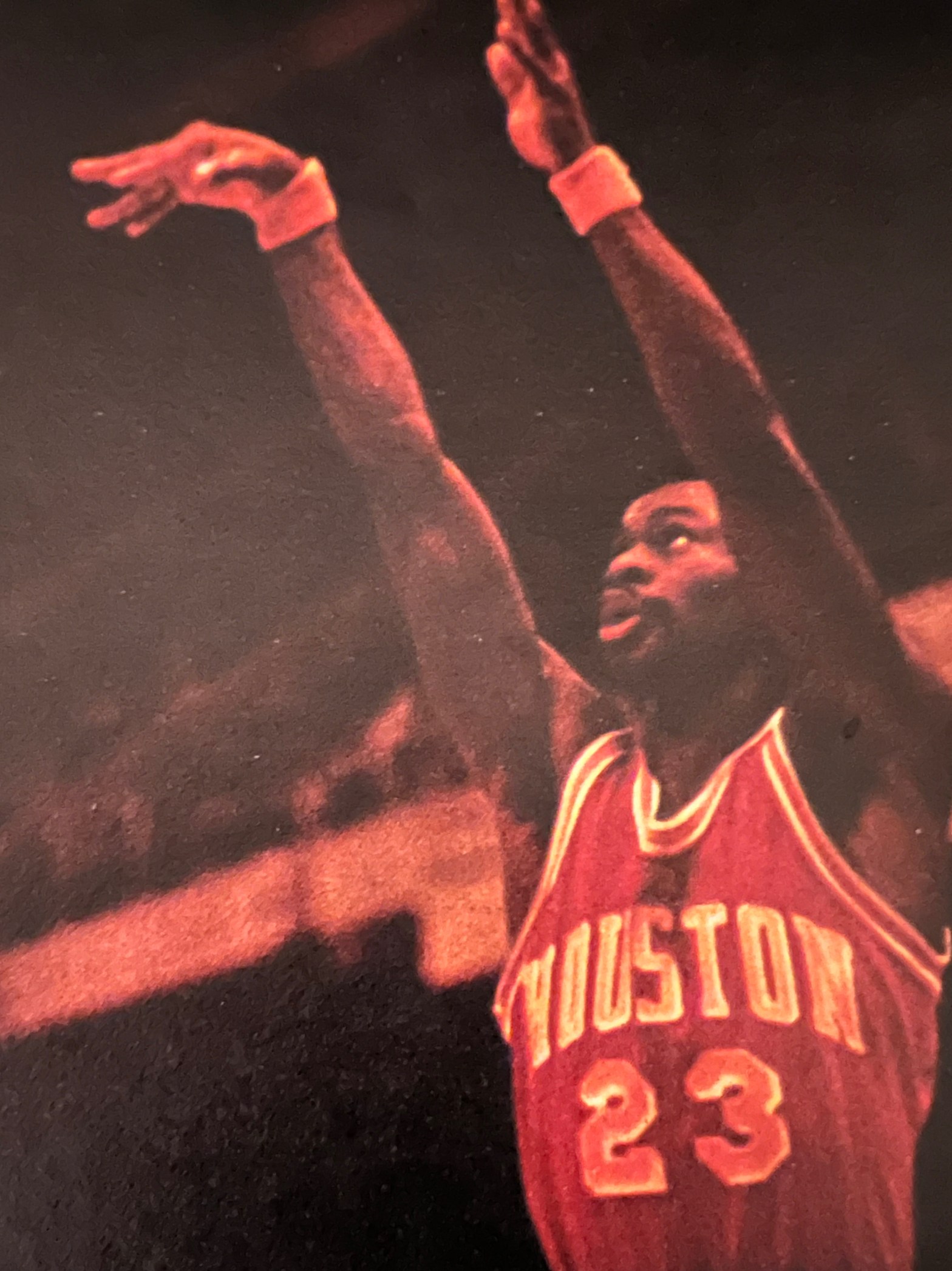

It’s been four years since Calvin Murphy slipped into his first pair of sneakers in the National Basketball Association. And for four years, the 5-feet-10 mighty mite of the Houston Rockets has learned what it’s like to be the smallest kid on the block. A modern-day David among Goliaths, Murphy is a firm believer that a little man in pro basketball is taking a bad rap. To him, tall is a four-letter word.

“People never let this rest about our size,” Murphy says, his foot tapping out rhythms. “In any facet of life, if the person can do the job—if he is capable and has the ability—I don’t think size is that important. Naturally, being the smallest man in the NBA, you’ve got to do things differently. You have got to be thinking 100 percent of the time. You have got to be a step ahead of your opponent. But if you have the ability, then there’s no other problem for you, except the problems that all ballplayers face—one game you are a hero, the next game you’re a dog. It has nothing to do with size.”

It’s hard to argue with success, and Calvin has sliced himself large hunks of it since the San Diego Rockets chose him in the second round of the 1970 draft. The Niagara University product water-bugged to his best professional season last year, averaging 20.4 points a game. He handed out 603 assists (second only to Buffalo’s Ernie DiGregorio), was fourth in the NBA in field-goal accuracy at .522, and sixth in the league in free-throw percentage with an .868 mark.

Life in the NBA has been a difficult test for Murphy, who has tried to prove that a small man can indeed play among the trees. While Calvin has no hang-ups about his size, he can’t stand being talked down to. “I blame a lot of my problems on what I call the little man stigma,” Murphy says. “We, as average-sized basketball players, have constantly had to prove ourselves. The stigma has gotten so strong, that no matter what your statistics read, other people feel that it’s a fluke—but it’s not supposed to happen this way. The little man is getting picked on. You can go paranoid, it happens so much.”

There’s no question that Calvin is one of the NBA’s better offensive performers, and his playmaking is above reproach. But what about his defense? Don’t the big guys exploit his shortcomings? “Don’t bet the ranch,” Murphy retorts.

“If anything, I think the little man has the advantage,” he maintains. “With the 24-second clock, the big man can’t really take advantage of us. With the fast, run-type games, this is to our advantage, being smaller and quicker. This is something that’s overlooked about the little man—we play the best defense in the league because we can go full-court. We can pick up, and we can scrap. We can force the bigger guards into a lot of mistakes, because the bigger guard are not really the ballhandling guards.”

“I’m a realist,” Calvin continues. “I’m not patting myself on the back or being cocky. You are not going to have a big man stop me. And if I run into a big man game in and game out, I’m going to run him down. Because I’m going to run him. And as far as him posting me, if he is going to spend all 24 seconds trying, I welcome it.”

Murphy never has felt insecurity about his own talent. Unfortunately, the Rockets have changed coaches three times in four years. The shuffling has kept Calvin unsure of where he stood.

“With every coach I had to start from the beginning and prove myself all over again. Every coach put me last, on the bottom of the list. They looked at my size, and then on down,” he recalls ruefully. “You get a coach coming in who never played a small man on his team and never felt the small man had a place. You’ve got to prove yourself to him. This is what I had to do. When I came to the Rockets, I played first under [Alex] Hannum, then under [Tex] Winter and now under Johnny Egan.

“I’ve had to change my game each time. One year, I’m a playmaker; the next year I’m a scorer. The next year, I can’t play at all because I don’t play any defense. It’s been very frustrating for me until now, since I’ve never gone into a season saying I have the job and somebody’s got to take it from me.”

No worry. Murphy has found a home in the Rocket starting backcourt with Mike Newlin. “Mike’s a good one,” Murphy appraises. “He’s a big, strong guard who can put the ball in the hole.”

Calvin is the Rockets’ little big man—small in stature, but big in ability. He’s made it in a sport dominated by men a foot taller. Throughout his roller-coaster first four years in the NBA, Murphy has taken time out to analyze his situation. It has helped him survive in the land of the giants.

“in my junior year in college,” he remembers, “when people first started talking about the pros, that’s when I first started getting the ‘little man syndrome.’ Forget his ability. He’ll never make it. His size will just never allow him to stay out there.

“It’s a funny thing,” Calvin concludes. “Ever since high school, I have always played taller ballplayers, and I’ve never had any trouble. Every year, it’s been getting easier for me.”