[A few weeks ago, the Naismith Hall of Fame announced the short list of candidates for its Class of 2024. Among the names was former Detroit Pistons center Bill Laimbeer. Some fans cheered the nomination, many groaned in head-shaking remembrance of Laimbeer’s low-altitude athleticism and evil-doer image. But if history is any guide, Laimbeer likely shrugged at his nomination. He has always worried about the things in his life that he can control. Getting into the Hall isn’t one of them.

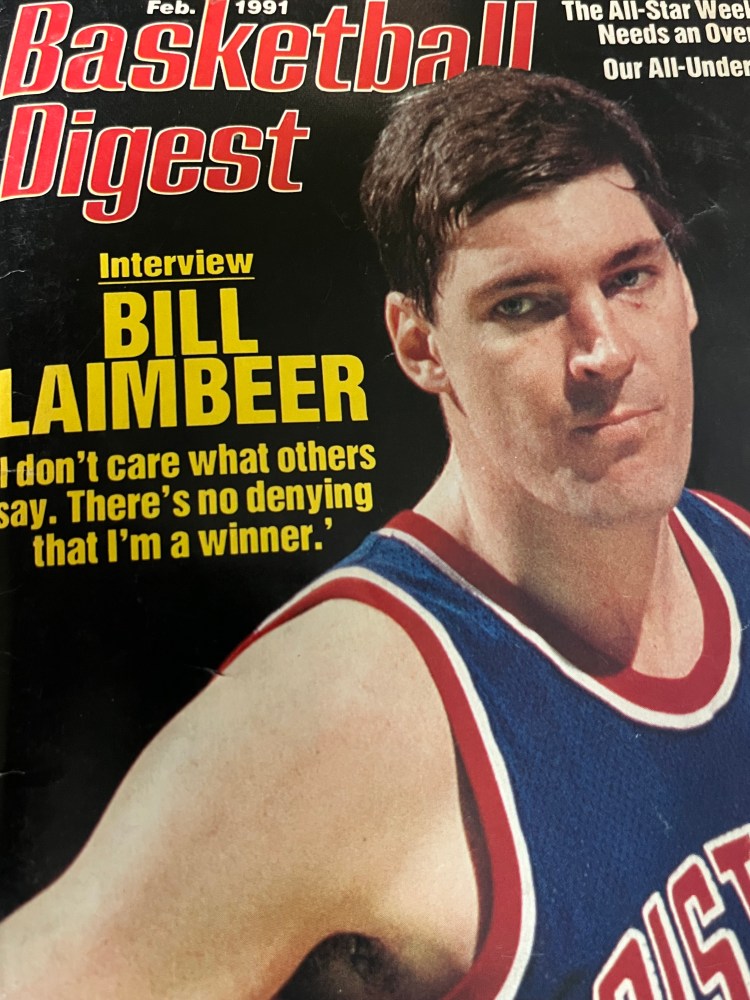

That’s the message in the following Q & A with Laimbeer, which ran in the February 1991 issue of Basketball Digest. The original headline—“The Interview”—sounds epic, as though Laimbeer is about to ponder the basketball universe. He’s not. The Q & A, conducted by Pistons’ beat reporter Drew Sharp, is fast-moving and will probably take you about five minutes to read. Interestingly, among the questions: Does Laimbeer envision a spot in the Hall of Fame? (I’ve already hinted at his answer.) But first, Sharp offers a brief intro. But one last thing. “BD” further below stands for Basketball Digest. Enjoy the read.]

He’s easily the most-despised player in the NBA, and one of the most-hated athletes ever to play professional sports. That is, when he’s not performing in front of the home crowd. Bill Laimbeer once had his jersey—already hung in effigy—chain-sawed at midcourt, much to the delight of a screaming Atlanta audience.

Laimbeer is the antithesis of the prototype NBA center. He’s allergic to having his back to the basket and has shunned all requests to develop a low-post game. Rather than change Laimbeer, the Pistons ultimately adapted their game plan to his strengths.

Laimbeer has made a career of blending brains and brawn. He’s one of the game’s deadliest perimeter scorers and, at the same time, one of its top rebounders. As a member of the two-time, defending world-champion Pistons, Laimbeer also is getting into the public eye more. He was the butt of a Kevin McHale joke on an episode of Cheers and was the focus of a !0-page cover story in Sports Illustrated in November.

****

BD: Do you feel that the Bad Boys stigma attached to the Pistons two years ago was unfair?

Laimbeer: Unfair? That’s a new one. I haven’t heard the description before. I don’t see why it was unfair. It was really just a promotional thing.

BD: Was it the league’s idea to characterize the Pistons as the Bad Boys?

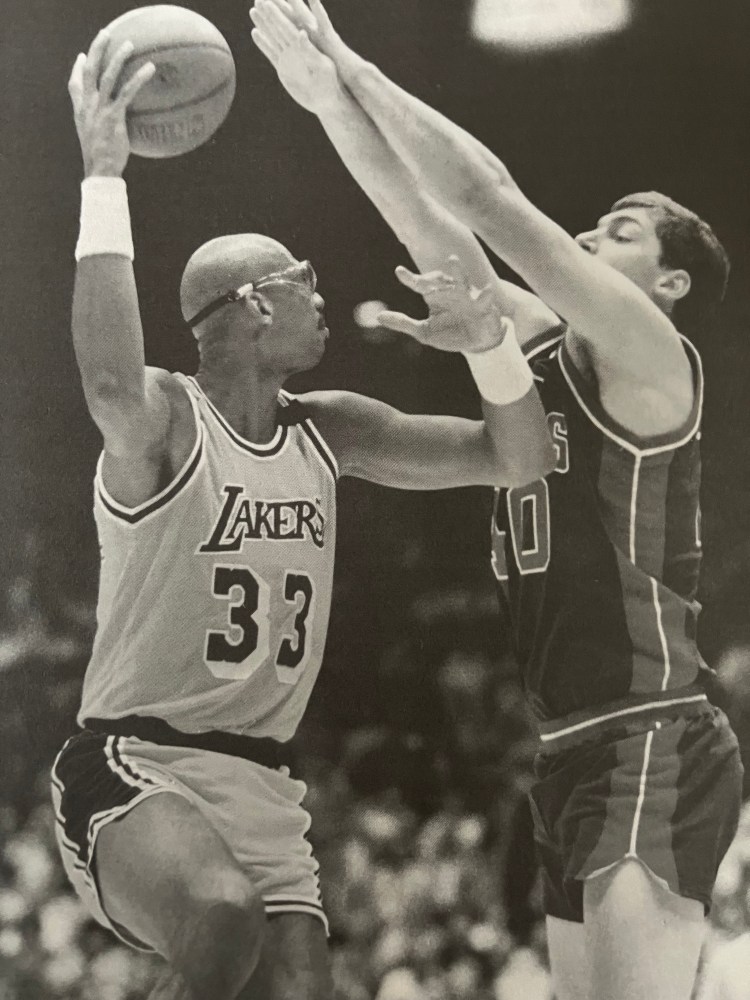

Laimbeer: They’re the ones who came up with the nickname “Bad Boys” after we lost to the Lakers in the 1986 NBA Finals. They picked the nickname for our video. We used it as a marketing tool. The team used it just to make money.

BD: Do you feel that it gave the team a needed identity?

Laimbeer: I think it gave us an identity and purpose, because we knew we were good, but we needed something to rally around. That seemed to be a good way to do it. They gave us that “us against the world” mentality that will push you to higher levels emotionally.

BD: In your first championship season, when Rick Mahorn was fined $5,000 for elbowing Cleveland’s Mark Price, did the team’s outrage over the fine make winning the championship truly a mission?

Laimbeer: It made us more focused on the fact that we were not liked very well around the league. And I think it spurred us on to play better the rest of the season. You could say that it provided the impetus for us to achieve greatness.

BD: Considering the way you play up the crowds on the road, such as when you bowed to the fans in Portland during last year’s finals, do you consider yourself an actor on a stage?

Laimbeer: We’re in the entertainment business, and you want to give the fans what they want. If they want great plays, they look for Isiah Thomas. If they want steady plays, they look for Joe Dumars. If they want comic relief, they look to me. That’s just the way it is.

BD: Doesn’t that place an emotional burden on you, having to be the teams designated whipping boy on the road?

Laimbeer: No, I don’t think it has any mental effect on me. I understand the business. It’s the entertainment business. Some people will dislike you because of the way you look or by the clothes that you wear. And some will just dislike you in general, for no apparent reason. I may fall into all three categories, but that’s just the way it is, and I understand that.

BD: Doesn’t there come a breaking point at some time when you say to yourself, “Enough is enough”?

Laimbeer: There may be a breaking point, but it hasn’t come yet.

BD: Your game has long been criticized. Do you get a sense of satisfaction that you’ve proven these critics wrong with a successful 11-year career?

Laimbeer: The only satisfaction comes from proving myself to those people who said that I wouldn’t have a good career and still think that I’m not a good basketball player. Those people don’t know anything about basketball. I proved that I am a good basketball player.

BD: Seattle head coach K.C. Jones said that eventually you’ll be in the Hall of Fame. Do you envision ever getting that kind of recognition?

Laimbeer: I don’t think about that because I have no control over it.

BD: Do you feel that you’ve paved the way for future Bill Laimbeer-like centers, or is your type of center an NBA dinosaur?

Laimbeer: I think the league these days is getting bigger, stronger, faster, and more athletic. But there will always be room someplace for the players who play team basketball and have sound fundamentals.

BD: Do you start thinking about retiring now that you’re in your 11th season?

Laimbeer: I think about it every day. I’m 33 and approaching those final years. But as the old saying goes, you wake up every day with a reason not to stop.

BD: What’s that reason?

Laimbeer: Money. More money is one of them.

BD: Is the spirit of competition another?

Laimbeer: That and, perhaps more importantly, a sense of loyalty to the organization and my teammates. I’ve got good friends on the team, and I’m not going to abandon them right now—not at this point, while we’re still on top.

BD: Have you considered the possibility of coaching when your playing career is over?

Laimbeer: This lifestyle is such a drain on your family that I can’t envision going into coaching, because you’re always on the road. You spend so much time away from your family, and it’s also so mentally demanding. But then again, you can never say never.

BD: Do you see yourself capitalizing on your reputation?

Laimbeer: I don’t believe that I’m making any money off the bad image that’s been stuck to us. When I’m blatantly using this image for commercial gains, I will almost always give that money away to charities.

BD: But what about the Converse ads that you did with Mark Aguirre that harped on the Bad Boy image?

Laimbeer: That’s my shoe company, so that’s different. I’m under contract with Converse.

BD: But don’t you see yourself capitalizing on this when you’re retired? A Lite Beer commercial with you in a Boston bar would be a natural. Would you do something like that?

Laimbeer: When I’m done playing a Lite Beer commercial wouldn’t be bad. But I tend to shy away from a lot of that stuff. I’m capable of doing it, but I’m not sure if I have the patience or desire to do that kind of stuff right now. We’ll have to see.

BD: How did you feel about your face gracing the cover of Sports Illustrated? Was that another sign of acceptance of your type of game?

Laimbeer: I thought it was a good story. I’ve never really cared if others accepted or disliked the way I played.

BD: How would you like to see yourself remembered in the NBA?

Laimbeer: it doesn’t really matter much to me how I’m remembered. The only people I care about are my teammates, my family, and my friends. They are the only ones that truly matter. They all know me as a person, and they don’t care how others may view me as a basketball player.

BD: But doesn’t everyone have to look at Bill Laimbeer as a winner, despite the evil image?

Laimbeer: People can say whatever they want about the type of game I play, but there’s no denying that I’m a winner. They have to say that I’m a winner, a world champion. But the important thing is that I already know that I’m a winner. I don’t care what others say. People are going to say different things or whatever they want about me. The only thing that matters is what I think.