[Gheorghe Muresan was one of the NBA’s most-humongous Oh Wows ever before chronic injuries sunk his career and sent him to an early NBA retirement by the year 2000. But this tallest of NBA longshots managed to log four full seasons in the League (1993-97) and finished with career averages of 9.8 points and 6.4 rebounds per game, while shooting 57 percent from the field.

In the excellent article to follow, journalist Paul Attner, then a senior writer with The Sporting News, presents Gheorghe Muresan 2.0 and his improving court skills. Attner, of course, couldn’t predict the season-ending injuries to come for Muresan, starting with his DNP during the next 1997-98 campaign. But this profile, featuring comments from myriad first-rate sources who characterize well Muresan’s gigantic game, remains fun reading more than 25 years later. Attner’s profile appeared in The Sporting News’ Pro Basketball Yearbook 1996-97. Just for the record, during the 1996-97 season—Muresan’s last without serious injury—he would average 25 minutes, 10.6 points (shooting 60 percent from the field), 6.6 rebounds, and 1.3 blocks per game.]

****

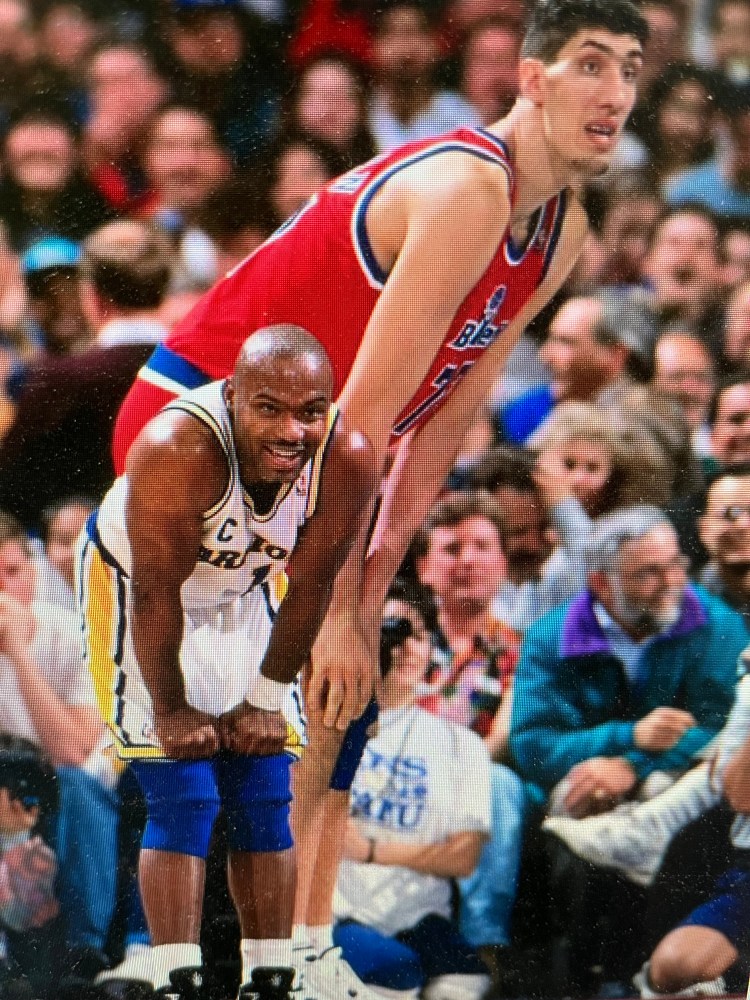

How big is big? I once measured big by the way my hand became lost during a handshake with Wilt Chamberlain. It was in there somewhere, engulfed by a huge piece of flesh and fingers and a ring the size of Mt. Rushmore. Big was when I walked up to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and saw nothing but his uniform number, since I was staring straight ahead, having failed to look up. Big was when I saw wrestler André the Giant riding a transportation cart through O’Hare Airport and, sitting down, he was taller and larger than anyone walking near him.

But all my previous references by which to determine big have been erased. Forever. For I have met Gheorghe Muresan. And, for me, nothing else will seem very big again.

I knock at the front door of his modest subdivision house located about 35 miles from Washington D.C., in suburban Maryland. The door opens, and the void is instantly filled by the huge figure of a man leaning over, so as not to bump his head on the top of the frame. Big can be intimidating—but this giant is smiling. I soon find he is a living happy face, laughing, and having a jolly good time. But for the moment, the smile makes it easier to comprehend what is before me. Isolated opposite all 5-feet-9-inches of me, he is a sight that holds no precedent. I try to act cool but, really, how do you not react nervously to someone 7-feet-7 and 310 pounds?

“Gheorge, good to see you,” I somehow stammer. I stick out my hand, and we shake. (Wilt’s hand, by the way, is fatter.)

“Come in,” he replies as he steps back and unfolds his frame full length. I do my best not to stare. He recognizes my hesitation. “People always ask me how tall I am,” he says. “I don’t mind. It is natural. They have never seen such tallness, so why wouldn’t they ask?” Jim McIlvaine, 7-feet-1 and a former teammate of Muresan’s, tried to prepare me for this moment. He says people see the Romanian and act stupid. He has even watched them become so distracted they walk into poles.

You look up and feel he could pick you up with a finger and twirl you around and drop you into a nearby wastebasket. You gaze again at his face. It is long and thin, his cheeks a bit gaunt. His eyes are wide, like some excited child, but at the same time, they are sad. Even when he laughs, they never sparkle; they are a casualty of rapid growth spurts that have separated him from everyone else. He’s wearing the longest pair of jeans you’ll ever see and a plain T-shirt. A TV is blaring in another room; it is, of course, a big-screen version. His wife, Liliana, who also is from Romania, is somewhere in the house. She is 6-feet-1, but standing next to her husband, she looks tiny. Lucky, his Great Dane, is outside, yapping away. It is time for his daily walk, but his master first must attend to business.

Two years ago, a reporter likely would have arrived at Muresan’s house out of curiosity about his life; how he wound up 5,000 miles from his homeland, playing for the Bullets. Not much would have been written about his basketball skills because, quite frankly, there wasn’t much to describe. He was a sideshow then, a quirk of nature whose overactive pituitary gland produced a giant human with enough ability to warrant a “what do we have to lose?” second-round draft pick in 1993. That Muresan was so big was the only valid reason for a story; “project” almost seemed too kind to describe his future.

“When I first saw him on tape, I thought the only way he could play in the league was if they put him on wheels,” says Bullets coach Jim Lynam, who was general manager of the 76ers when Muresan was drafted. “I thought his lack of mobility was insurmountable.”

Now Lyman looks at the tallest player in NBA history and sees something else. “A legitimate player,” he says. Lynam is a basketball junkie, a Philly guy who digests hoops more eagerly than he does food. He speaks in basketball shorthand, tossing out simple phrases that mean volumes. Praise is not a basketball junkie’s strength; Muresan has passed stern tests to become “legitimate” in Lyman’s eyes.

And that is why I am sitting in the family room of Muresan’s house, looking at Gheorghe from eye level. This remarkable accomplishment has been brought about through the miracle of me sitting on a leather sofa and Gheorghe sort of sitting and ducking his head and folding up his body. It is his kind way of making himself less formidable. Now, of course, I also can boast I stared straight into the eyes of a 7-feet-7 guy.

I want to find out how Muresan made the transformation from freak to force. In just his third NBA season, playing on an injury-marred team that changed from a 1994-95 embarrassment to a 1995-96 playoff contender, he developed into a mostly dependable scorer (14.5-point average) and a frequent intimidator who no longer could be minimized by opponents. He led the NBA in field-goal percentage (58.4), was ninth in blocks (2.26), and was chosen the league’s most-improved player.

Not bad for someone who, when he first joined the Bullets, could not do one pushup, could hardly run the court without falling down, and could barely stay out of foul trouble long enough to lose his breath. The club thought so little of his chances that it wanted him to spend another year playing in Europe.

But Gheorghe, if nothing else, is tall and independent. Tell him to do one thing, and he likely will do the opposite. He wanted to try the NBA, so he signed a non-guaranteed $150,000 contract and remained in Washington. Last offseason, the Bullets asked him to stick around for conditioning; so, he went to Europe instead to play for a month.

His independent streak has much to do with his development. He is aware of how he was initially viewed in the league. “When I first came here, a lot of people say, I can’t play in the NBA,” he says, speaking in broken, but steadily improving, English. He is smiling as he talks, letting you know that he thought fools were making those comments. “That’s OK, you never know. I try every day to play much better, much better.”

But could he make it? “Why not? When I come here, the league is very hard for me. I didn’t know the players, I never lifted before, the travel, the language, the practices, everything was different. I don’t feel very comfortable lots of times. But I see where my work is working. My ability goes up, up, up. So, I keep working.”

Proving the naysayers wrong has not been easy. Medical problems were the first obstacle. A large benign tumor was pressing against his pituitary, gland, causing his unusual growth (neither of his parents reached 6 feet). After the draft, he had serious surgery that could have led to blindness; that was followed by radiation treatments to minimize the tumor size and give him a normal life expectancy. He now takes daily medication to help prevent the tumor from enlarging.

He became close to Dennis Householder, the Bullets’ strength and conditioning coach, and the two began from scratch to upgrade Muresan’s body. It is, obviously, a different body. Back then, he had a potbelly and weighed 330 out-of-shape pounds and could bench-press only 100 pounds. His chest is narrow, and although he can sit and reach and stretch far beyond his toes, he had no flexibility in his thighs.

Householder taught him how to run—Muresan has knock knees and still can’t lift his legs very high—and they worked on exercises to improve Muresan’s balance and agility. His height prevented him from using most weight machines, so they improvised, employing free weights to increase his strength. Unspoiled and enthusiastic, Muresan loved it; he became a gym rat, playing and exercising daily. During one summer workout, he lost 10 pounds. Householder became concerned, but by the afternoon session, the 10 pounds were back. How? Muresan had consumed unknown quantities of watermelon at lunch. (A fruit lover, he has been known to buy out a local stand near the Bullets’ practice facility, sending employees home early.)

The more comfortable he became with his new body, the easier it was for him to improve on the court. When he joined the Bullets, he had decent skills, particularly a fine shooting touch and sticky hands. But his lack of mobility was a killer; he couldn’t move very far very fast, certainly a problem in a game based on quickness.

Wes Unseld, then the team’s coach and now its general manager, was skeptical about how successful the experiment would be. After all, then-GM John Nash had drafted Muresan almost on a whim after watching tapes of him playing on a French pro team. Still, Unseld made a wise choice—he decided to use Muresan in brief spurts his rookie season, refusing to allow his confidence to be destroyed by too much exposure against far more polished opponents. That also allowed Muresan time to grow healthy and improve his conditioning.

When Lynam took over from Unseld before Muresan’s second season, he had changed his mind about Gheorghe. He now saw him as a backup center to Kevin Duckworth. The Bullets’ staff began working on Muresan’s footwork and low-post moves, a process that continues even today at every practice. But language was a problem. The Bullets had hired an interpreter, and everything the coaches wanted to say to Muresan first had to be translated. Lynam finally had enough; he told Muresan he’d give him 10 basketball phrases to learn in English, stuff like “use both hands” and “box out.” Muresan said OK, but in return, he would give Lynam 10 phrases to learn in Romanian. Lynam thought it was a terrific comeback.

“It made you remember the human element,” Lynam says. “He was learning basketball. But he also had a language problem and a cultural problem, and how would you like to cope with being 7-feet-7 every day? Just getting in and out of cars and through the doors is a challenge. But Gheorghe had a perfect attitude. He is such an engaging guy, smart, and fun to be around. You couldn’t help but like him.”

By midseason, Muresan had replaced the overweight and underachieving Duckworth in the starting lineup. He finished with a 10-point average, nearly double the previous year; and shot 56 percent from the field. By the fall of 1995, he had developed a nice hook and a turnaround jumper, reflections of perhaps the best shooting eye on the team. In shooting contests, his teammates get upset if Muresan is allowed to fire away from even 15 feet. He inevitably makes six or seven in a row, quickly eliminating the competition.

“Gheorghe has gotten this far because he really wants to be a player,” Householder says. “He didn’t grow up in America, so he doesn’t think it’s beneath him to work hard.”

What the Bullets have now is one of the top 10 centers in the league. “I think he should be banned from the league,” says Spurs coach Bob Hill, in a kidding manner. “He’s got illegal height.” Muresan’s largeness also has impressed Heat coach Pat Riley: “He really changes the game because of his size.” And how does that work? “Well, he’s so long,” Toronto’s Ed Pinkney says, “but there is not much you can do with him when he backs in. Who’s going to block him?” Certainly not Dikembe Mutombo, a shot-blocking specialist, who spent one game last season swatting away in vain trying to alter even one of Muresan’s attempts. “He’s a force as long as you let him near the basket,” the 7-feet-2 Mutombo concedes.

Denver GM/coach Bernie Bickerstaff thinks Muresan already is considerably better than former Utah star Mark Eaton “in terms of touch and shots. He’s better than a lot of players period.”

“I’m impressed,” the Spurs’ David Robinson says. “He can be difficult to play against. I’m big, but he is bigger. You have to use your quickness to offset his size.”

“I love to watch him play,” Bullets teammate Tim Legler says. “If he catches the ball in deep, you can’t stop him. He can turn and score at will. Do you know how many big guys seem to miss easy shots? Not Gheorghe. He practices the short ones all the time.” And the Bullets enjoy seeing how foes cope with Muresan’s elbows. When he turns, they are at face level of a 7-footer; inevitably, inadvertent contact follows.

Muresan certainly is unlike any other NBA player. When he runs, he doesn’t straighten out his legs, so he moves in a bent-knee, laboring fashion with his feet barely off the floor. When he gets the ball in the low post and turns for his hook, he already is at rim height, and the shot seems to streak straight into the basket, moving so quickly it defies blocking.

The better he plays, the more he moves into the NBA mainstream. Last season, he got into a shoving match with Charles Barkley and a vocal exchange with Alonzo Mourning, who dunked on him one game and accented it with some woofing. “He said ‘face,’” said Muresan afterward, missing the “In your” part of Mourning’s boast. Muresan later blocked a Mourning attempt to turn around the game. “Dumb,” said Muresan about his opponent’s tactic.

If you analyze NBA players, using a series of steps, with step three being the top, Muresan is a step two. If he doesn’t improve anymore, he still is looking at a lengthy career. But there’s an upside. If he can become more consistent from game to game and week to week, and if he learns to handle the double-team better and his passing and court awareness improve—things the Bullets feel still can be taught—he can become an even bigger factor. Surely, he’ll always be at a disadvantage against quicker centers, but at the other end, how can they control his size and shooting ability?

“I’m not very good,” Muresan says. “I must be more consistent. Some weeks good, some weeks bad; same with some games.” But Gheorghe, can anyone really stop you one-on-one? He thinks. “No one,” he answers. Liliana, listening in the background, laughs at him.

The Bullets, who were 39-43 last season, appear ready to leap into the playoffs this season, provided free-agent forward Juwan Howard returns. But Muresan is a key player as well. That is something he couldn’t have imagined 11 years ago when he traveled from his home in Triteni to Cluj, the provincial capital, for a dental checkup. There, a worker in the office saw a 14-year-old boy who was 6-feet-8 and asked if he wanted to play basketball. Muresan, whose sports interest had been confined to soccer, eagerly agreed to leave Triteni, where the family house had no heat or electricity (“life very tough under the communists”), and begin learning hoops on a high school team.

By 20, he was performing internationally, both for his country’s team and as a pro in France. Later, he bought a house in Triteni for his father (his mother died during his first Bullets training camp) and a bakery for his brothers. All have heat and electricity. Despite his size, Muresan in many ways hasn’t grown up. He’s a big kid who loves to play practical jokes—he’s been known to turn the hot water off in the locker-room showers and lock teammates out of their hotel rooms—and have a good time. He enjoys malls and fine restaurants, and so what if he attracts attention? He’s not going to lock himself away, denying himself life’s pleasures.

So, Gheorghe Muresan turns heads, signs autographs, answers stupid questions, and lives as normally as he can. Except for his bed, his home has no specially made concessions for his height. He drives a turbo diesel all-purpose vehicle—there is some disagreement over his driving habits; he says he drives at medium speed, others contend he lives in the fast lane—and, other than problems finding clothing that fits and having to eat American food that mostly is not appealing (he lives on pasta, chicken, and fruit), he has no complaints, no moods, no anger.

Look at the upside: He can change light bulbs without a ladder and is in the midst of a four-year, $5.4 million contract. Talk to anyone who knows him, and they inevitably smile and give you their best imitation of his fractured English. He is, without question, the most-popular player among his teammates.

The doorbell rings. It is the neighborhood kid asking if Gheorghe can play. He frequently plays basketball with children in the subdivision. And he loses. “They are much faster with her hands,” he says. The games, of course, are on Sega. He is teaching himself how to use a computer; he already has his own email address. He and Liliana want their own children; he’d like two, a boy and a girl. But that is in the future. And he isn’t looking too far ahead.

“If I wasn’t playing basketball,” he says, “I am not sure what I would be doing. When I stop playing, I am not sure. It doesn’t matter. For now, I am basketball player.”

And a legitimate one, at that.