[In the summer of 1971, the ABA signed its first dominant seven-footer in Artis Gilmore. In this article, veteran reporter Howie Evans tagged along with the rookie for his first preseason games, offering a timeless snapshot of the pressures facing him as the ABA’s great equalizer and Kentucky-based center of media attention. Evans’ piece ran in the January 1972 issue of the magazine Black Sports.]

****

If predictions ever become reality, one day the name of Artis Gilmore will find its rightful place in basketball history. Before him, the names read: Joe Lapchick, George Mikan, Bill Russell, and Wilt Chamberlain. In their respective eras, they were the big men of the day.

Only Wilt Chamberlain overlaps the coming of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (Lew Alcindor) and Artis Gilmore era. Kareem has, in two seasons of professional basketball, proven himself to be one of the best big men in the history of that sport. Gilmore has yet to do so.

When Artis Gilmore signed his name on the contract, finalizing his decision to play professional basketball in the American Basketball Association (ABA), tremors of delight swept through Louisville, Kentucky. At last, the hometown Colonels had their big man . . . not just another big man, but one who at 7-feet-2, gave all of the indications that he would become another Bill Russell. With 6-feet-9 super-rookie Dan Issel, the league’s leading scorer in 1970, Kentuckians were predicting a dynasty that would equal the glory years of the Boston Celtics, led by Bill Russell and Bob Cousy.

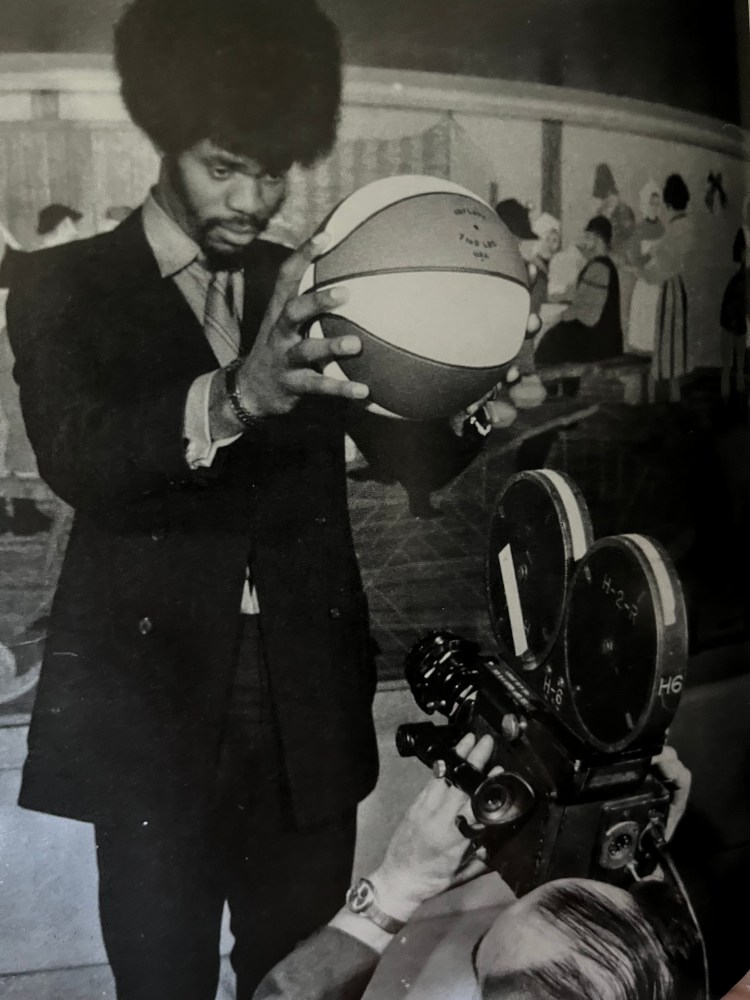

Having the most-heralded big man since Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the Colonels did not waste much time putting their million-dollar baby on display. They quickly hustled Artis to New York, where he met the big-city press. That was in April, right after the NCAA finals, when Gilmore was still recuperating from the shock of losing to Western Kentucky in the semifinals.

“I guess that has been the biggest disappointment of my career so far,” stated Artis. “I really wanted to end my college career with that championship, but I guess it just wasn’t for our team.”

The glare of the press’ television lights caused Artis to squint as he fumbled with a half-empty glass of water, waiting for the press conference to begin. Naturally, the questions revolved around his contract and the American Basketball Association vs. the National Basketball Association. Artis neatly underhanded those questions to his lawyer.

Meanwhile, back in Louisville, the Colonels’ public relations department was busy putting together ideas that would take full advantage of the coming of Artis Gilmore. One of the things they were working on was a preseason exhibition schedule that would give as much exposure as possible to their new star.

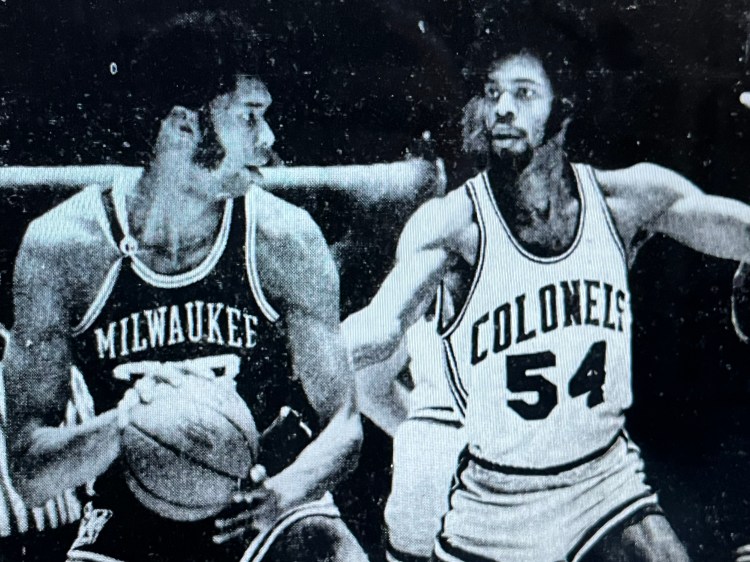

They came up with an unrealistic, backbreaking exhibition schedule that included 18 games against the likes of the Baltimore Bullets, Virginia Squires, Milwaukee Bucks, and New York Knickerbockers. It was more like sending the lamb out to be slaughtered.

On Wednesday night, September 22, at Freedom Hall in Louisville, the Colonels took on the Bullets and defeated them, 111-85. Over 13,000 fans viewed that contest and its history-making outcome. It marked the very first victory of an ABA team over an NBA team.

The day before that history-making game, someone had stepped on Gilmore’s foot during practice, and his big toe had swollen and become sore. But he was a pro now and determined that the 13,000 fans would not be denied the opportunity of seeing him in action against one of the better clubs in professional basketball. Gilmore limped up and down the court as he scored 14 points, grabbed 16 rebounds, and blocked shots that had the Bullets thinking perhaps Bill Russell had come out of retirement.

After the Baltimore game, Gilmore forgot about his toe and trudged back to his hotel room, where he listened to music for a couple of hours before falling asleep. The Colonels would be getting an early start for Richmond the next morning, where they would meet the Virginia Squires on the Virginia State College campus, a predominantly Black school in Petersburg, Virginia. Artis would be getting his first taste of the road—pro style.

And so, after a restful night, Gilmore and the Colonels hit the road for Virginia. Upon arriving in Petersburg, the Colonel’s descended from an ancient double-decker bus. There was no way you could miss Artis Gilmore. Clad in a soft-looking white suit with matching shirt and tie and a pair of leather boots, there was no mistaking Gilmore for anything but what he is—a young man with a million.

Slung over one arm was a garment bag that swayed rhythmically with his strut and the sounds coming out of a tape deck he held tightly in his other hand. “He carries that tape with him everywhere,” laughed Walt Simon, the Colonels’ nine-year veteran pro from Benedict College.

Once in his room, Gilmore quickly shed his shirt and tie, pulled off his boots, and relaxed in a chair that disappeared behind his massive body. Aretha Franklin was into a deep thing about “Spanish Harlem.”

With a flick of a finger, Artis brought the room to instant quiet. He leaned back in his chair and began talking in a voice as rich-flowing as syrup and similar to the muted tones of Miles Davis’ trumpet.

Artis recalled his years in Chipley, Florida, his birthplace, as ones of just hanging around with no place to go. “I spent most of my childhood there. When I was there, they didn’t have any place for the teenagers to go, and there was nothing to do. I thought the people there were very conservative.”

The folks Gilmore refers to as conservatives in the small town of Chipley might be called racists by others. He hates to offend people and goes out of his way to avoid situations that would embarrass him or others. “I hate to come down on people,” sighed Artis. “I would rather keep my mouth closed and walk away.”

Artis also attended school in New York City and finally graduated from Carver High School in Alabama, but he most vividly recalls his days at Chipley High. Artis talked good-humoredly about his days there.

“You know, I never considered going to college when I was in high school back in Florida,” Artis reminisced. “I had a little bit of fun but didn’t prepare for college. I was like a lot of athletes; I wasn’t concerned about the books, just basketball and trying to impress the girls.”

Chipley High was such a small school that Artis got a chance to play basketball with the varsity as a freshman. “Yeah,” laughed Artis, “my game was so far behind the other guys, I ended up on the bench. Really, the only reason they put me on the varsity was that I was just as tall as the varsity center.”

As a freshman, Aris was 6-feet-5, the tallest kid in the school. He grew slowly between his freshman and junior years, but he sprouted up three inches during the summer before his senior year. He was 6-feet-9 ½ when he started college.

Artis came from a family that was not well off, and his height presented problems. “I was not really self-conscious about my height, but the family financial situation was pretty bad. I was very conscious about my clothes, because my parents couldn’t afford to give us nice things like other kids had. The stores down there were very limited in stock, and a lot of my clothes didn’t fit properly. I always compared what I had with what the other kids had.”

Trying to improve the family’s financial situation was not easy for Artis. “One thing about Chipley was that there was no place to work, so people couldn’t really make money. There was nothing to look forward to. During my high school days there, I worked picking up watermelons for five dollars a day. Chipley was the watermelon capital of the world, “ Artis laughed.

Life is going great for Artis now, but just thinking about those days brings a saddened look to his face. “Hey look,” Artis said suddenly, “I want to get something to eat and then look for a record store.”

So Artis, after a late lunch and now in a pair of striking red slacks and matching two-tone shirt, left the hotel in search of some soul sides. “Don’t walk too fast,” he cautioned. “My toe is killing me.” His passion for the sounds of today was obviously greater than the pain shooting through his leg with every step he took. Back at the hotel, after buying $70 worth of cassettes [$522 today], Artis lay back in bed and thought about the game, which was just five hours away.

So intense was the pain in his toe that Gilmore skipped the pregame warm-up period and rested in the dressing room. The Squires, led by Charlie Scott and Julius Erving, defeated the Colonels, 131-128. Limping up and down the court, Gilmore batted away 10 shots, grabbed 12 rebounds, and scored 14 points before fouling out with a little over one minute to play in the third quarter.

The Colonels had staked their whole future in Gilmore, but unwisely, perhaps, “threw him into the wolves’ pit,” according to Charlie Scott. “I don’t understand why they scheduled so many games. He will be dead before the season begins. Look who he has to go against—Unseld, Abdul-Jabbar, Reed, McDaniels; it just isn’t right.”

According to the Kentucky preseason prospectus, one of the strong points of the Colonels was their offense. They averaged 122.2 points per game last year . . . second in the league. The best offensive player in the league last year was Dan Issel, who scored 2,470 points to lead the league.

Going after Gilmore, the Colonels got who they thought was the best defensive big man in college. None other than Bill Sharman, the coach of the Los Angeles Lakers, predicted, “The Colonels will be the first team in the ABA to battle the Milwaukee Bucks on even terms—Gilmore will be to the Colonels what Bill Russell was to the Boston Celtics. He will be an intimidating defensive player who can set up their fastbreaks and allow a great player like Dan Issel to concentrate more on offense.”

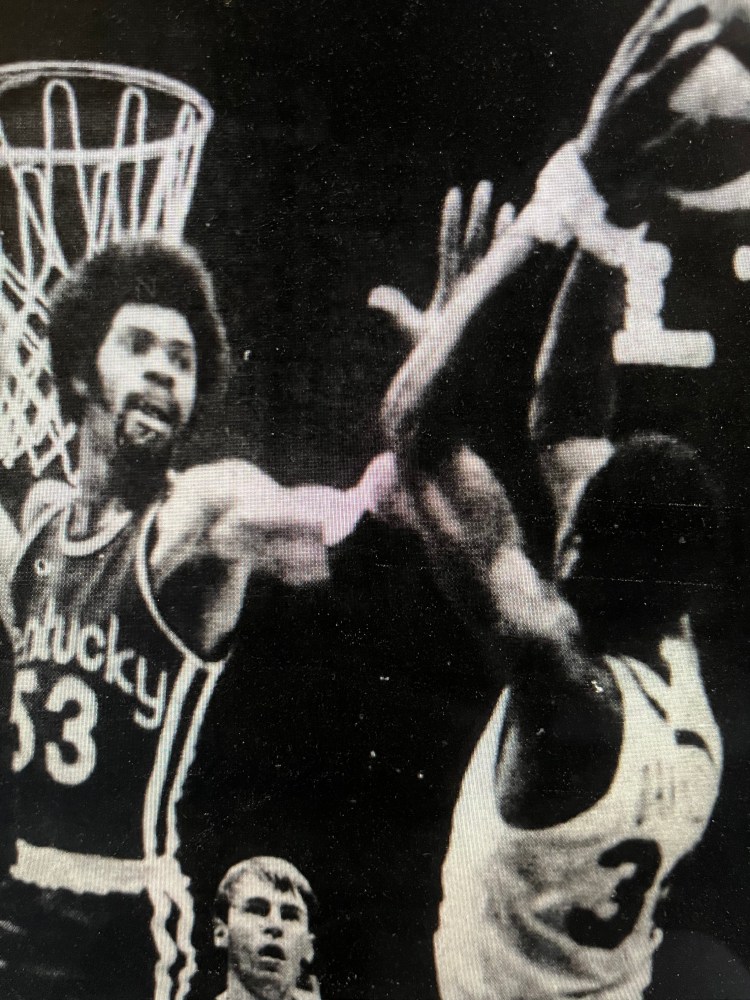

On the night of October 8, a standing room crowd at 18,000 fans jammed Freedom Hall to witness the much-awaited confrontation between Kareem and Artis. Abdul-Jabbar came out on top, but the consensus of those present was that Artis did not embarrass himself. He held his own, at least on the floor of battle, if not on paper, where the stats of the game gave the edge to Kareem.

The splendid center of the Milwaukee Bucks scored 30 points, snatched 20 rebounds, and blocked three shots in 39 minutes of action. Artis, the somewhat reluctant rookie of that night, didn’t do badly. He hit 18 points, swept the boards for 16 rebounds, and sent back five Milwaukee field goal attempts. The basketball-loving folks of Kentucky got what they paid for—a hand-to-hand confrontation between the two biggest men in professional basketball.

Artis was not pleased with his performance, and he asked a reporter from Jacksonville, Florida, where he played college ball, not to tell the folks how we performed. Joe Mullaney, the former coach of the Los Angeles Lakers and certainly a man in a position to compare, stated after the historic meeting, “Gilmore did more than a credible job. He certainly held his own. The things the bothered him were simple matters of experience. Most of these things will come to him as he plays more.”

Kareem quickly agreed with what Mullaney had said. “He’s going to be a good player. Those hooks he throws up are tough to block.”

Larry Costello, the Bucks’ coach, had this to say after the encounter: “He needs experience. Once he gets those moves perfected around the basket, he’s going to be tough to stop or contain. He’s a leaper, a defensive player; he just needs experience.”

In Gilmore’s first real big test, his inexperience was obvious. He picked up four first-quarter fouls, three of them on high school mistakes like climbing over Kareem’s back scuffling for rebounds. One foul came when he barged into Kareem rolling to the basket. Kareem had anticipated such a move and established his position, thus causing Artis to foul.

Once during the contest, Artis brought the partisan crowd to its feet when Kareem swung around for that patented, soft hook shot of his. Artis went high and smacked it into the stands. The crowd loved that, and they went crazy.

The gameplan devised by the Bucks, however, worked to perfection. They took advantage of Artis Gilmore’s inexperience and went right at him. Kareem was the boss after Gilmore picked up that fourth foul in the first quarter. Kareem later stated, “Artis could have played better, all around, if he had not been in foul trouble. There is no question in my mind that he will be another dynamic force in professional basketball.”

“Playing against Abdul-Jabbar must have been an experience for Artis,” stated Dave Vance, publicity director for the Colonels. “It is the first time that Artis has played someone who could look him in the eye or look down on him.

“Artis is a shade over 7-feet-2, but even with his Afro, he gave up an inch to Kareem,” said Dave, shaking his head. “I had my doubts about Artis, but after tonight, I know that he is going to be one of the best in the game.”

Whatever Artis is doing now, his preseason performances against the four top centers in the game indicated that he is indeed worth every dollar of the reported $2-million contract that the Colonels gave him to sign.

In preseason exhibition games, Artis scored a total of 88 points against Wes Unseld, Willis Reed. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Mel Daniels, while giving up 59. He grabbed 74 rebounds, against 50 by the quartet. He blocked 21 shots, while he had only four of his blocked. This is possibly not a fair comparison, but it does give a statistical breakdown of Gilmore’s effectiveness.

The money invested in Gilmore by the Colonels will be paid back before the season is over. In the preseason exhibition games against the Milwaukee Bucks and New York Knickerbockers, the Colonels drew over 30,000 fans. And for those who feel Gilmore is overpaid, according to the crowds that his presence is drawing, he is grossly underpaid.

Once all the furor dies down and Gilmore gets down to learning his trade, basketball fans will be able to compare Artist in more objective terms. He is learning to live with the comparisons to Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. “It’s not fair for people to compare me with Alcindor,” Artis quietly states. “He is in his third year of pro ball, and I am just getting started. I guess I understand, though. Who else could they compare him to?”

Artis is neither Kareem Abdul-Jabbar nor Bill Russell. He is simply Artis Gilmore, a big, talented, quiet, young man, who, by the time this basketball season is over, will have made his presence felt not by comparison, but by his own accomplishments.