[The Washington Wizards, formerly Bullets, have made several big-time roster moves since I relocated here in the 1980s. One of the most promising was the arrival in the mid-1990s of the young Chris Webber, who had NBA superstar written all over him. This celebrated pairing of team and superstar would eventually end in irreconcilable differences and the Wizards abruptly unloading Webber on Sacramento, where the sidewalks roll up at 10 p.m. and where Webber didn’t want to be. But Webber soon would revitalize his career in Sacramento, my hometown, and memorably rue to a Washington Post reporter, “You could have had all this.”

Warning: What follows is LONG journalism about the 22-year-old Webber trying to find himself in Washington, before the irreconcilable differences to come. But the prose in this article, published in the February 18, 1996 issue of Washington Post Magazine, absolutely sings, and the story remains very much worth the time. Doing the honors is the great David Finkel, who is still publishing great stuff. In fact, he’s got a new book about to drop. If you like this article, consider buying his new release on our divided country. I know I will.]

****

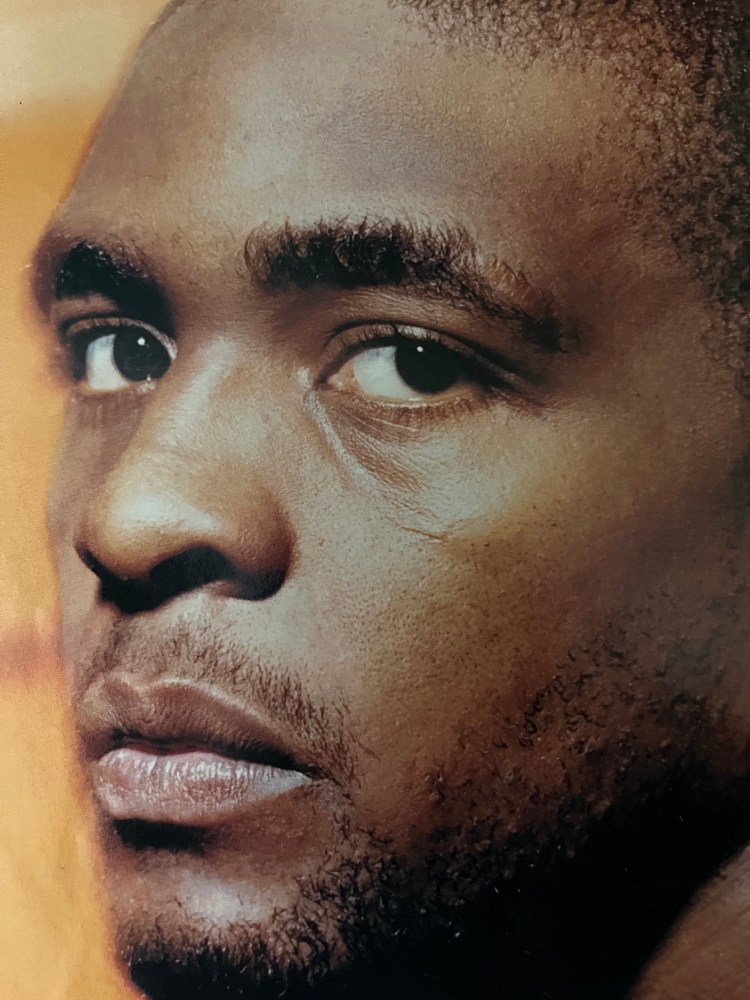

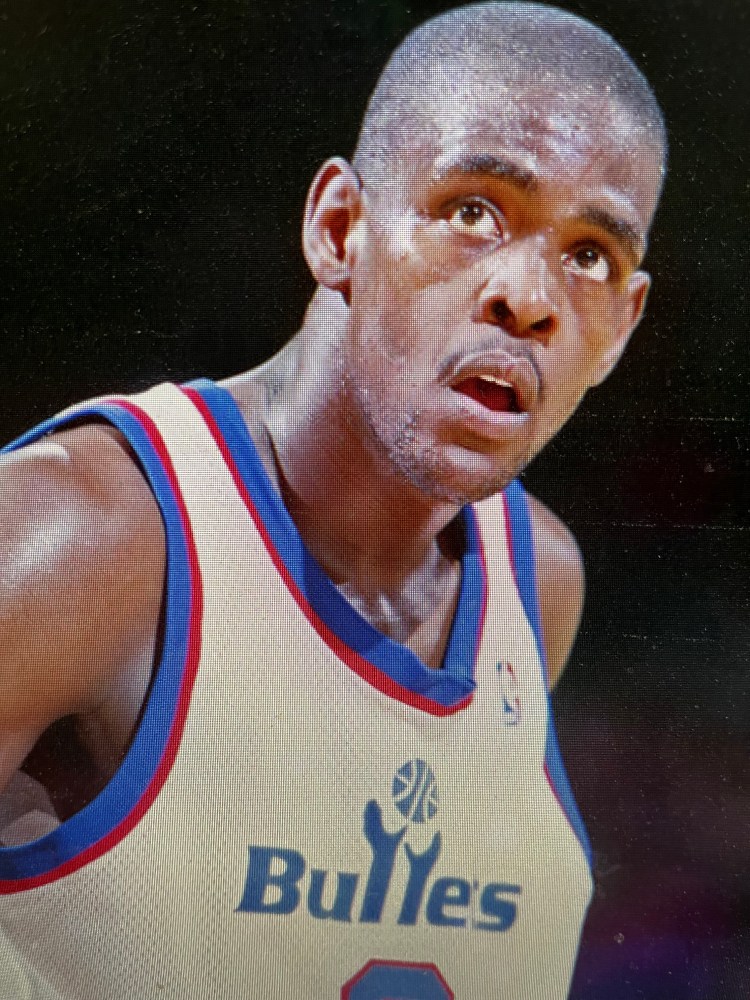

At the moment, the shoulder is fine. Chris Webber flexes his left arm to show that this is so. He reaches behind his back. He stretches for the sky. See? No problem, none at all. There’s no looseness. There’s no grinding. There’s no popping. He grabs a basketball. Up come the arms, the shoulder rotates, and away goes the ball as Webber, the savior of the Washington Bullets, attempts to shoot a foul shot.

Clunk.

A little short.

Zero for one.

This is in December 1995, at practice. It is seven weeks before his season will come to an end. It is two months after his shoulder fell out of its socket in the preseason and a few days after one of his first games back, a game at USAir Arena against the lowly Milwaukee Bucks in front of a measly crowd of 10,126. Webber was the star of the game, but, for him, this is what it came down to: 44 seconds left, the Bullets were up by one, he was fouled, he had the chance to give his team some breathing room, he missed the first shot, he missed the second, he walked over to one of the other players and said, “I messed up.” And now, here he is.

“If you bring it up fast, real fast, then you’re in serious trouble. Bring it up slow,” says his shooting coach Buzz Braman, and Webber tries again.

“See?”

One for two.

Regular practice, at this point, is over. The rest of the team is gone. It is just Webber out here, shooting behind closed doors, sealed off for the moment from all of the people who love basketball, who love the NBA, who love him, who pay $25 for nosebleed seats to see him jump and dunk, who buy the $48 jersey with his name on the back, who buy the $140 sneakers with his initials on the back, who emulate every facet of his game, down to his baggy, low-hanging shorts and black socks and the hair-raising screams that sometimes fly out of him after he makes a shot.

Two for three.

“Yes!” says Braman.

Three for four.

Webber, meanwhile, says nothing at all. Not a scream, not a taunt, not a word.

Three for five.

And his shorts are pulled up around his waist.

Five for eight.

And his socks are white.

Thirteen for 18. Fourteen for 19, 14 for 20, 14 for 21 . . .

He is trying to concentrate. He bounces the ball. Sometimes, to steady himself, whether in front of Braman, or the rest of the Bullets, or 10,000 people at USAir Arena, or the 19,000 who watched his high school championship game, or the 50 million TV viewers who watched his college championship game, he bounces the ball while repeating the names of his brothers and sister. Jeffrey-bounce-Jason. David-bounce-Rachel. And sometimes it works.

Fifteen for 23.

There’s so much these days. There are so many people who want his time, who want his autograph, who want the use of his name, who want merely to be near him.

Sixteen for 24 . . .

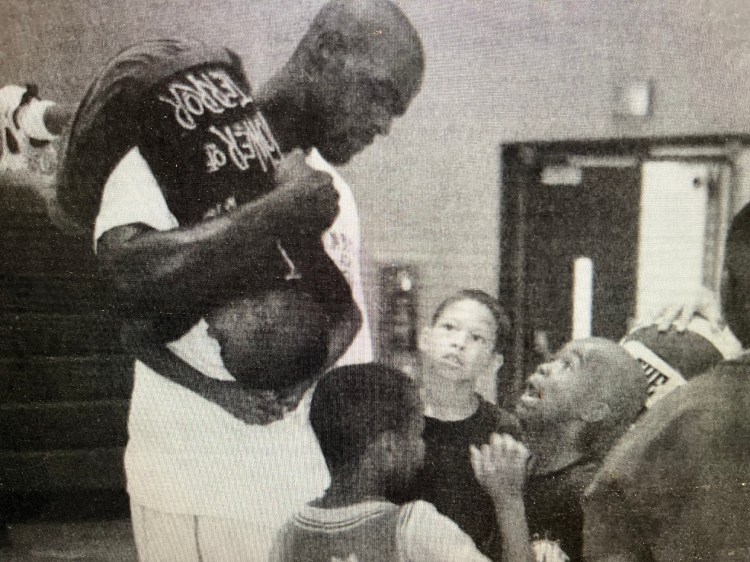

There are so many expectations of him, including, not the least of them, his own. These aren’t mere basketball expectations, but something more. They have to do with helping people, especially children, especially Black children, especially Black children in his hometown of Detroit, especially Black male children in Detroit’s inner city. He wants to save them, just as he feels he’s been saved, and he is sure this will happen because it is nothing less than the plan of God.

Seventeen for 26 . . .

Except since coming to Washington 15 months ago, that plan has gotten somewhat out of whack.

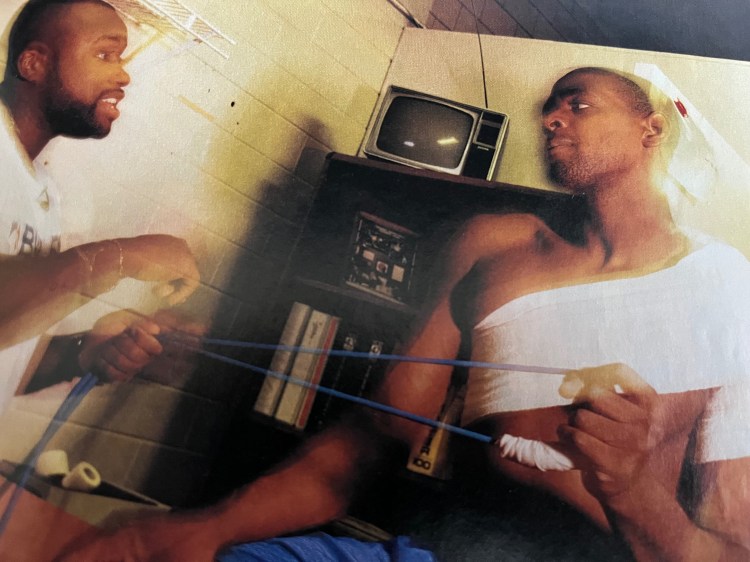

The shoulder has been dislocated twice. The dislocations led to long stretches of idleness. The idleness led to periods of feeling depressed, which is something that a professional basketball player, especially one with a $57 million contract, isn’t supposed to feel. But he did, and of no comfort was the knowledge that the next dislocation could come at any moment. During sleep. Getting dressed. Driving to practice. Reaching for the ball. Shooting the very next shot.

But a plan is a plan, and Webber’s starts with basketball, and so on a day that offers the hint that, maybe, at last, everything is getting back on track, he keeps at it—50 shots, 75, 100—until, after 104 attempts, 78 of which go in, Braman calls it a day.

They slap hands, and Webber heads for the locker room, where he straps on an ice pack, sits by his locker, and talks about his ultimate goal in life, the one above basketball, the one above everything. “I want to be a man of the people,” he says, so heartfelt it’s sweet, so earnest it hurts, but as he keeps talking, it becomes clear that what he wants even more is to be thought of as a man, period.

****

He isn’t. Not yet. Not in his mind, at least, and to see a bit of his life is to wonder whether he will ever have reason to think otherwise. He is 22 years old, indulged and protected. He is adored for the mere fact of coming to the Washington Bullets and vilified for the mere fact of leaving his previous team, the Golden State Warriors. He is imitated, sought after, gossiped about, and recognized wherever he goes, and it’s all because he exists in a peculiar little world in which the worst thing you can do is grow old.

There is nothing new in this, of course. By its very nature, the world of professional sports has long been a kind of cradle, where young men try to stay exactly that because to grow up is to be gone. Think of Mickey Mantle, who appeared not to become an adult until he was 63 years old and about to die. Think about John Riggins and Mike Tyson and Pete Rose and a hundred others. Think about how hard it can be to grow up under ordinary circumstances, and measure that against the role sports plays in society: Each year it seems to get exponentially larger, with stars who make so much money, and are regarded so highly, that they are guaranteed insulation forever from the mundanities of everyday life.

Especially its basketball stars.

When Alonzo Mourning negotiates a new contract this summer, he wants at least $13 million a year for seven years. Shaquille O’Neal, meanwhile, is likely to want more than that, and Michael Jordan, who earned an estimated $44 million last year between his contract and endorsements, wants, well, who knows? The only certainty in this is that one of them will become the highest-paid basketball player of all time, eclipsing the player who has that distinction now, none other than Webber, whose average annual salary of $9.5 million for the next six years is guaranteed in almost all circumstances, even if he becomes a bad player, even if he’s permanently injured, even if he’s hit by a bus.

So, he is rich. And talented. But most of all he is young, so much so that if things had gone more normally for him, he would be barely out of college at this point, starting to make his way. But of course there has been nothing normal about his progression, only an aura of inevitability. He was a 6-feet-5 object of curiosity in middle school, who became the best high school player in America, who became the centerpiece of the University of Michigan’s celebrated Fab Five, which played in the NCAA championship game in both his freshman and sophomore years.

Both times his team lost, but each game added to the inevitability, especially the game in his sophomore year, when, with his team behind by two points and only a few seconds left, he brought the ball down the court, got hemmed in by the other team, called for a time out that his team didn’t have, left the court in a daze, took full responsibility for the loss, found his mother, laid his head in her lap, and wept. In that miserable way, his college career came to an end. Soon after, he left school for the NBA, became the No. 1 pick, and now, in his third season, he finds himself at the center of a world that includes a company formed to handle his business affairs, another company to handle fan mail, two charitable foundations, a summer basketball camp, a Webber’s World fan club, two agents, an attorney, a part-time security guard, a friend from high school whom he pays to drive him places and go with him to parties and make sure no one tries to spike his drink, and, beginning last fall, a personal assistant fresh from a stint with Whitney Houston, who keeps a minute-by-minute schedule of his time.

Such is his life. There is more:

There are endorsement deals that divide him into parts—Nike has the rights to his body from the neck down; LogoAthletic has a separate deal for his head.

There is a cleaning service with a contractual agreement to never, ever discuss the contents of his house. There is a caterer, whose job is to have fresh, healthy food waiting for him whenever he walks into the house after a home game, and to fax a list of that food once a week to his family, who want to make sure he’s eating well.

There is the Mercedes. There was a Humvee. There’s a big house. There is the continuing search for land upon which to build a bigger house, perhaps, as big as the house he bought when he was in California, which his aunt, Charlene Johnson, an attorney who helps handle his business affairs, describes as “quite a presentation.” She remembers the first time the Webber family saw it, after Webber was living there, when the real estate agent picked them up at the airport, drove them into an exclusive gated community and kept going until they found themselves in another, more exclusive gated community within the community. “She said, ‘There’s the house.’ We said, ‘Where?’ She said, ‘Up on the hill.’ We looked up the hill, it was just as though I heard the music from [the TV show] ‘Dynasty.’ I had nightmares the first night. I have never stayed in a place so large. We were like the Beverly Hillbillies.”

All because he can play basketball.

At games, he’s always introduced last, and always gets the loudest ovation, and always manages to do something that brings an entire crowd to its feet. One night, against the Los Angeles Lakers, it’s a spinning dunk in the fourth quarter that puts the Bullets ahead for good, and up comes everyone, roaring, and he responds by stabbing an index finger in the air, and they respond by roaring louder, and among the loudest of all are 30 people who are at the game entirely because of him, because earlier in the year, out of his desire to be a man of the people, he wrote a check to the Bullets for $33,670, which got him 30 seats to every game for the rest of the season. Sometimes the seats are given to friends, but mostly they are given to students at the various areas schools where Webber speaks now and then. The students get to see a game for free, and afterward they are escorted to a secured room under the stands, adjacent to the locker area, which is where they are now, applauding as he walks in.

“Thank you for coming,” he says. He reaches out, shakes a girl’s hand, moves on, doesn’t see her reaction, but at this point wouldn’t be surprised if he did. It’s as if she has touched greatness. She stares at her hand. She lifts it to her face. She closes her eyes. She inhales.

****

It is this way all the time. It isn’t one girl but a thousand. It isn’t one game, but every game since he was in eighth grade and a story about him appeared in one of the Detroit papers under the headline, “He’s so young, but so talented.”

His father, Mayce, says, “One guy offered me a thousand dollars for Chris’ baby shoes.” His mother, Doris, says, “Why do relatives come to games and stand in line? That one gets me. These are people who changed his diaper, and they’ll stand in line to see him and get a hug and to be seen in public.”

His Aunt Charlene says, “During the season, the mail comes in boxes. He’ll get maybe 500 letters a month: ‘I like you.’ ‘I saw you.’ ‘Will you come to my house for dinner?’”

Most of the mail ends up at a small office Charlene maintains in suburban Detroit, all of it responded to, some of it filed away. She reaches into a pile and pulls out a letter that has yet to be answered, from a woman inviting Webber to her 4-year-old son’s birthday party “because I know every single parent dreams about doing something special for their children.” “Why would he go to a 4-year-old’s birthday party?” says Charlene, wondering how to respond. Maybe a poster? Maybe a T-shirt? ”Perhaps we’ll order a cake.”

She finds another letter, this one written in late December from a woman inviting Webber to a party as soon as he can get to her house. “Dear Chris,” it begins. “You are the only thing my son Uri wants for Christmas! Besides me staying healthy. I have cancer. We thought it was gone, and I just found out it is back. Uri does not know. You both are born March 1, so I was going to wait till then, but now I am not sure I have the time . . .”

So he gets those kinds of letters, too, and gifts, and poems, and pictures, and phone calls, one of which came in early December and concerned a 12-year-old named JeVon Rogers, who’d attended Webber’s basketball camp over the summer. “It was really inspiring,” JeVon’s mother, Anita, says later, explaining why the call was made that day. Her son, she says, lost his father a few years before, had been somewhat sad and quiet since then, was starting to drift a bit, and then he spent a week at the camp and came home wonderfully changed. She says he began talking about attending the high school Webber went to, began eating healthier, began talking about going to college. She says he truly seemed more engaged in day-to-day life, simply because he’d gone to the camp and met Webber, and that this continued through the fall and into early December when he was crossing the street and a driver, talking on the car phone, ran into him, and he went flying into the air and came down on his head and lived long enough for her to get to the hospital and see him die, and that was the reason for the call, to see if there was any way Webber could come to the funeral.

He couldn’t. He simply couldn’t. He had a game. But Charlene says, “We sent a floral arrangement, it cost $150, we sent a telegram, it cost $75, and I attended the funeral.”

To which Anita Rogers says with gratitude, “It was a cold, snowy day when he was buried, and yet his aunt took the time to come.”

Of which Charlene says that, every day, she is amazed at the effect a 22-year-old who plays basketball can have on people’s lives. She says, “What has he done? I’m not trying to be facetious. What has he done to make him a role model?” She says, “If our definition of a role model is a person who completes high school, attends college for two years, and gets a job, then he is a role model. But if we expect something more of our role models, then he may not be.”

She says, “When I think of our role models, I think more along the lines of Martin Luther King,” and she tells about another phone call, this one from a woman named Bridget, who first sent a fan letter, then sent a framed poem, and now was calling to say she was establishing a home for disadvantaged children and wanted to name one of the rooms after Webber. “I said, ‘Bridget, what if you had named one of your rooms the O.J. Simpson Room? Why do you want to do this? Is it because he’s an athlete?’ I said, ‘We’re really pleased that you want to do this, but I don’t think it is proper to name a room the Chris Webber Room.’”

To which Webber says that the question of whether he should or shouldn’t be a role model misses the point. “I am a role model,” he says, and so is every athlete. That’s why, at Bullets games, kids show up in his jersey. It’s why, when he was in college, more and more kids began wearing baggy shorts; that’s why when he was in high school and shook hands with Isiah Thomas, he spent days wondering if the rough skin on Thomas’ fingers was the secret to his success; it’s why, when he was a kid himself and his idol was Charles Barkley, he mimicked him to the point of trying to walk like him.

Barkley, of course, is one of the most complicated figures in sports, having evolved from someone who once spit on a young girl in the stands (his excuse was that he was aiming for someone else and missed) into his current incarnation, the grand and revered Sir Charles. If anyone could be a role model for Webber these days, at least in terms of how long it can take to grow up in the NBA, who better than Berkeley? Except a few years ago, he starred in a sneaker commercial in which he declared, “I am not a role, model,” and “Just because I dunk a basketball doesn’t mean I should raise your kids,” and now that Webber knows him, plays against him, and occasionally is compared to him, he wants almost nothing to do with Barkley at all.

“The fact is that young people will listen to Barkley before they listen to their parents,” he says one afternoon, trying to explain this. Five days before, his aunt made her way in the snow to JeVon Rogers’ funeral. Two days before, Webber was sitting in front of his locker after a game, and the TV cameras were on him as usual, and an assistant brought over a beer wrapped in a towel, and asked if he wanted it, and Webber discreetly took him aside and told him never to do that again. Now, at this moment, conversation has turned to the subject of obligations.

He says: “I do respect Barkley as a basketball player. I don’t really respect Barkley as a Black man in the Black community.”

He says: “It’s up to him to speak up and take licks for standing up for the community, and he doesn’t do that. I know he doesn’t do that.”

He says: “It’s what you do off the court. It’s how you treat your responsibilities.”

He says: “His is obligated. When he was born Black, to me, he was obligated.”

****

“Chris Webber is a young guy,” Charles Barkley says in response to all of this. “With age comes wisdom. And he will get more wise in his old age.”

This is in Phoenix, just after the Suns have beaten the Bullets in overtime, largely because of Barkley. The Bullets, meanwhile, had been on a good run until this night, winning five games in a row, the first time they’ve done this in 6 ½ years, largely because of Webber. Despite concerns about his shoulder, he’d been consistently strong and frequently spectacular, zipping passes, sinking shots, saving games, prompting Bullets coach Jimmy Lynam to say at one point, “I think it’s obvious what kind of player he is. He’s the best player on our team, one of the best players in the league, no question. There’s no question.”

Against Barkley, though, he wasn’t a factor at all. Just before the game, he went down with an injury—not to his shoulder, but to his ankle, somehow twisting it while trying to scoop up a ball. He spent the entire game in the locker room, flipping through channels on the TV in there, icing the ankle down and watching it swell, and now, after the game, he seems absolutely forlorn.

“It’s a sprain,” he just about mumbles, eyes down, clearly wanting to say nothing more. He sits by himself. He has the perfect athlete’s physique, but the mind of a mere human, and sometimes he can’t help but wonder why these injuries keep happening to him, which always leads him eventually to the same answers: “It’s God’s plan.” And, “I’m blessed.”

Now, a day later, in California, where the Bullets have come for a game against Webber’s first NBA team, the Golden State Warriors, he is saying exactly that to a group of reporters surrounding him as he lies on a training table. “Chris, do you feel kind of snakebit sometimes?” is the question.

“Nope,” he says, his voice flattening into a mixture of sincerity and autopilot as he launches into an answer that he’s given a hundred, a thousand, a million times in his life, especially to himself, “because I’m blessed. God has blessed me. And these little things I’m complaining about, it’s great to even be able to play. I could have twisted my knee yesterday, tore the ligament in my knee, so: God blessed me.” All of which gets written down and reported in the next day’s papers because Webber remains a big name out here, not so much for the way he played, which was good enough to get him the NBA’s Rookie of the Year award, but for the fact that he left.

It was a departure that was ugly in every way. He came to Golden State as the long-awaited missing link who would, over time, lead the team from its perennial also-ran status to the championship. From the beginning, however, he and coach of the Warriors, Don Nelson, had problems. Nelson is an old-style coach; Webber is a new-style player. Nelson uses tactics such as calling first-year players “Rookie” rather than by their first names to let them know where they stand; Webber finds such tactics demeaning, no matter how much of a tradition they might be. This has long been a theme with him, back to his high school days when he was a scholarship student at an exclusive private school called Detroit Country Day. One of the school’s traditions involved an appreciation dinner for students and faculty in which the scholarship students were expected to serve the food; harmless enough, perhaps, but Webber said he didn’t want to participate, that it would put him in the position of seeming servile.

In that instance, the school excused him, but Don Nelson is loath to excuse anyone, for anything, and at one point, in the middle of a game, in an extraordinary scene, the two began screaming at each other, Nelson about Webber’s attitude and Webber about Nelson’s inability to, as he would describe it later, over and over, “treat me like a man.” From that point on, things declined steadily, until, at the end of the 1993-94 season, Webber turned his back on what was supposed to be a long-term commitment to Golden State, exercised an escape clause in his contract and ended up in Washington. Nelson, meanwhile, coached the team for a while more, but eventually he was hospitalized for what was said to be a combination of pneumonia and exhaustion, and then he resigned, and the Warriors fell apart, and ever since, though Webber may be adored in Washington, in Northern California he has been despised.

So deep is this feeling that at his first game back there as a Bullet in December 1994, the booing began immediately and continued all the way into the third quarter, when he dove for a loose ball and ended up motionless on the floor. This was his first shoulder separation. The pain, it is said, is unbearable, and as he lay there, trying not to scream, the booing finally stopped. But only for a moment. Because as he was helped to his feet it began again, and it followed him all the way into the locker room where, behind closed doors, several people had to hold him still, while a doctor maneuvered the arm up and down, back and forth, until as Jim McIlvaine, a Bullets player who was one of the people holding him down, describes it, there was a suction-type sound, followed by a cracking sound, and the shoulder slipped back into place. Sometime after that, his arm in a sling, Webber emerged to watch the rest of the game from the bench, and as soon as he appeared, the booing resumed.

And now, a year later, the fans are at it again. He is introduced. They boo. He touches the ball. They boo. A guy named Mike Morales is walking around carrying a huge sign with a drawing of Webber dressed up like a baby, yelling over and over, “Hey Chris! Hey Chris! Hey Webber!” A guy named Marc Cervellino is explaining over the noise, “He gave these fans hope. He broke their hearts.”

A guy named Bob Beaulieu is saying, “Wait till he leaves Washington. You guys’ll feel the same way we do.” Third quarter: The Bullets are down by 20, the game might as well be over, the crowd, finally, is quiet. But not for long. “You suck, Webber,” comes a cry from high in the stands, and at first there is a little laughter, and then applause, and suddenly the whole place is cheering.

And meanwhile, back in Washington:

“It was like the fulfillment of a dream,” Susan O’Malley, the president of the Bullets, is saying about the day Webber left Golden State for Washington.

She tries to describe what life was like before then. There was the ugly blazer contest to fill seats when the Portland Trail Blazers came to town. There were the ad campaigns that focused on Jordan and Magic and Bird and hardly mentioned the Bullets. There were her marching orders to flood the local media with story ideas in the flush of success when Washingtonian Magazine featured a Bullets player in a story about barbecuing techniques. “Ain’t too proud to beg,” is the way O’Malley characterizes those days, and then came November 17, 1994.

“In 24 hours, we sold a thousand season tickets. It would take us a summer to sell a thousand tickets. I remember a sales guy standing on a chair right after and yelling, ‘The phones do ring,’” she says, and to illustrate the wonder of those first days she turns on the TV in her office and puts a tape into the VCR. “We gathered together and watched when it aired,” she says, as the screen fills with the image of Webber talking to David Letterman. “You have to understand the evolution. We couldn’t get a mention on [syndicated sportscaster] George Michael.”

Webber, at that point, had been a Bullet for two weeks.

“How’s it going so far?” Letterman laughed, and now, watching this, O’Malley laughs, too. “I mean, tell me that’s not charming,” she says.

****

But the truth is that by the time Webber was on “Letterman,” he was already feeling himself beginning to sink. “I walked around dead last year,” he is saying one afternoon. “I walked around emotionally dead. I didn’t go anywhere. I didn’t do anything. I was a hermit. It was very hard last year.”

This is something Webber hasn’t talked much about, mostly because by the time he left Golden State, he was being regarded less as the sympathetic character he’d become after calling the timeout in college and more as the embodiment of selfishness, of greediness, of immaturity. “Last year, if I said anything, it would be associated as me complaining,” he says. So he said little at all, but as the weeks wore on he found himself increasingly depressed, a feeling no doubt exaggerated by one unshakable point: “I did not want to come here.”

He wanted, he says, to be in San Francisco. He wanted to be in his $2 million house, the one on the hill, the one he had finally finished furnishing just before his trade. He wanted to be, and to remain, a Warrior. “You know, people say I’m greedy,” he says, “but I could have gotten more money, and been winning sooner, and been on TV more, and been in a place where the weather is warm every day, and there are beaches every day, and there are convertibles every day, and the women are beautiful every day—why would I want to leave?” But he had no choice, he says, because to stay would mean “I would have egg on my face,” and at his agent’s urging, he drew up a list of half a dozen teams he was willing to consider being traded to, including, to the Bullets’ surprise, them.

He came to Washington to meet with Abe Pollin, the Bullets’ owner. He left and said, “A lot of teams have made inquiries about me, but the Bullets are the only one I’m interested in.” Now he concedes that that wasn’t exactly true, that he was really thinking the Bullets, in various ways, were “the worst out of the six,” but of course he couldn’t say such a thing at the time, just as when things were beginning to sour with Nelson, and he was asked about it, he answered, “I definitely don’t have any problems with Coach at all.”

Besides, the decision of where he would go wasn’t entirely his, but also Golden State’s. It was a complicated matter of salary caps, and which players the Warriors would get in return for letting Webber go, and on it went for several days until Webber’s agent finally called him to tell him what Golden State had agreed to: Washington. A team that the previous season, the same season in which Webber was rookie of the year, had 24 wins and 54 losses.

Home of the ugly blazer contest.

“I wasn’t surprised,” Webber says. “They did that to spit in my face: ‘Now you’re a Bullet.’”

But at least it was settled, which was exciting enough for Webber to get on a plane, fly all night, arrive in Washington at 8 AM, go to USAir Arena, hear of the unbelievable ticket sales and, in spite of being exhausted, agreed to play in that night’s game. Which was a loss. As was the next game. As was the next. As was the one after that. “There was so much going on,” he says, “it didn’t hit me till my 10th loss.” And then? “I felt like I was about to have a nervous breakdown.”

He means this. It isn’t hyperbole. That’s how bad it got. “When the Don Nelson situation came down, I would sit and cry,” he says, “but this, somehow, seemed worse. “I’m losing. I’m here. The fans were cheering for the other team.” None of which had happened to him before.

Then came the game against Golden State, followed by five weeks of not playing, followed by a loss when he finally returned. Followed by: three more losses, a win, and six more losses. Followed by a stretch in March and April of 13 consecutive losses—and somewhere in there, after talking to him on the phone and hearing his voice and watching him on TV and seeing his eyes, his mother began leaving constant messages on his pager, biblical passages intended to, if not cheer him up, at least give him perspective.

On the year skidded. “I got hurt. I came back. I wasn’t an all-star, I wanted to be an all-star, I was crushed” is how he sums it up. “We lost. My grandfather died. My girl left me. Blah-blah-blah. But there were so many things.”

How did he finally get through it?

“I didn’t.”

Instead, he says, the season simply fizzled out and a new one began, and by the time he was once again rejuvenated, feeling strong, feeling hopeful, feeling blessed, until a preseason game in October, against Indiana, in which he tried to steal the ball from someone and his shoulder became separated again. “It’s dislocated! It’s dislocated! It’s dislocated!” he kept screaming. He collapsed on the bench. He was taken to the locker room. This time, the shoulder was even more difficult to get back in place. He had to be sedated to the point where he was barely able to speak, and then, in the following days, he had to decide whether to have surgery and give up the season or delay surgery as long as possible, undergo rehabilitation, and try to keep playing, knowing that the shoulder was almost certain to separate again.

The best argument for surgery was that the shoulder would be permanently fixed in time for next season. The most-cynical argument was that he would get his millions either way. The best argument against it was that by delaying the surgery and trying to play, he would show that he wasn’t selfish, wasn’t greedy, was in it for the team, and that’s how the decision was made.

It was ultimately his call, and now, in late December, after a dozen games back, he is sure it was the right one. He is feeling a long way from how he felt last year. The shoulder is holding up. The team is winning more than it’s losing. “We’re turning it around,” he says, and what better proof could there be of this than the game, the previous night, in which he scored 40 points and played, perhaps, the best game of his career? It was a performance so emotionally satisfying that now, this day, he finds himself looking forward to everything ahead, starting with the next game on the schedule against the New York Knicks, who got a new coach this year and recently have been on a tear.

That coach, as it happens, is Don Nelson. He has been rejuvenated, too. His team, though, starts out a little slow. The Bullets get an early lead, build on it, are up by 16 points in the fourth quarter, but then the Knicks start coming back until, as time runs out, the score is tied. The game goes into overtime. The Knicks go up by two points. Webber gets the ball. He drives to the basket. Everyone is screaming. This is what he loves best. He has already scored 19 points, this will be easy, maybe a dunk, maybe a reverse dunk, he needs only to get around a Knicks player who is down on the floor, except he catches his foot somehow and trips and goes flying and can’t break his fall and lands hard, and out pops the shoulder again. But only slightly. And then, as he lies collapsed, emotionless once more, he feels it go back In.

The diagnosis Is a severe strain. The word is, he’ll be out a week, maybe two, perhaps three. In fact, this is the injury that will end his season, but now, sitting in the locker room, he has no way of knowing this.

“It could have been worse,” he is saying.

“I’m just thankful right now . . .

“I’m just glad it’s not as bad as it could have been . . .

“I just thank God . . .”

****

He means this, too. He does thank God. Constantly. He prays every day. He takes a Bible with him on road trips. He tithes: $500,000 last year. He finds absolute comfort in the notion that God has a plan for him—it’s just the day-to-day details that sometimes leave him wondering what is going on. “I think that’s probably what he’s asking,” his mother says one day. “What is the plan?”

She is, at the moment, in the house in suburban Detroit, that she and her family moved into last year, courtesy of her son, in the living room, near the baby grand piano, a few steps away from the elevator, on the third floor. Level four is the bedrooms. Level two is the gym and a pool table shipped from the California home. Level one is the garage with the 10,000 Chris Webber T-shirts in boxes, and the rider mower to take care of the 3 ½ -acre lawn, and the first gift that a grateful son was able to buy for his father, a Cadillac, which was only fitting since the father has spent the last 27 years in an automobile plant building those very cars.

In other words, it’s a good life the Webbers have these days, far more luxurious than the one they had when they were living in a small house on a so-so block in the city, but it doesn’t mean everything’s settled. There’s still the matter of feeling satisfied on a deeper level, Doris Weber says, which is why she continues to be a teacher, and why her husband continues to work in the Cadillac plant towards his pension, and why, when their millionaire son comes home to visit, he’s usually filled with questions that suggest, if not unfulfillment, a kind of continuing search.

For instance: “How does he know he’s a man? That he’s achieved manhood? It’s more than having a job, and taking care of a family, and having dreams, so how do you know when you’ve arrived? Or is it an ongoing process? Those are the kinds of questions he has,” she says.

His father, meanwhile, is remembering a trip the family once took to Tunica, Miss., long one of the poorest places in the United States. This is where Mayce Webber was raised, and though the trip was ostensibly a family vacation, he also wanted his son to see a few things, for the sake of perspective, before his basketball life got too big. There was Sugar Ditch, for instance, an open sewage drain running through a part of downtown containing nothing but shacks and the poorest of Black people. There was the countryside beyond town, which can get so dark on a starless night, that when the Webber children first stepped out of the car, they grew so scared, so quickly, and felt so invisible, that they began screaming for their father to turn on the headlights. There were the small houses in the woods, some home to Webber relatives, one of which had a good, wide set of front steps, where Mayce sat one afternoon with his 12-year-old, 6-feet-5 son, wondering how best to explain what life had been like for him at that same age. He decided, at last, to tell him a story.

“It was in the evening” is what he remembers saying. “I was coming from town, and as I was walking, just before I got to the cemetery, I saw these guys on a truck, six or seven or 10 of them, and I saw this Black guy running across the field, and they drove over and got him, and were beating him up and shooting in the air . . .”

And now, so many years later, Mayce Webber is saying that he was reluctant to tell this to his son, that “I didn’t want him to have vengeance,” that “I just wanted him to go forward,” but that he also wanted him to be ready for whatever might be ahead.

Back they went to Detroit, to a life that grew increasingly complex: offers of cash that Mayce says got up to $20,000 when it came time for Chris, 14, to choose a high school; offers of up to $200,000 in cash when it came time for Chris, 18, to choose a college; offers after that of $3,000 for Chris’ letterman’s jacket, $5,000 for Chris’ first pair of athletic shoes, and from one mother, $1,000 if Chris would simply walk around with her son at the mall, where they could be seen together.

To a lower middle-class family, the money was pressure enough, but within Chris at 14, at 16, at 18, came pressure from an increasing awareness that he was on a different path from most of his inner-city friends, that his life was destined to be good, that he wasn’t ever going to be chased down anywhere except perhaps by people wanting his autograph, and out of that awareness came a kind of survivor’s guilt. More and more, he would describe the street he lived on—racially mixed and relatively crime-free, according to Mayce—as part of the ghetto. He also began saying that his family was so poor, there would be nothing to eat but beans for a week at a time—a fact, Mayce says, that had less to do with his autoworker’s salary than his wife’s desire to send all the children to private schools. “Otherwise,” he says, “we would have had it made.” Regardless, guilt can lead to a sense of obligation, which can lead to a desire to rescue, which can lead to, say, a plan for a private school in the inner city to save all of the people left behind, and that’s the idea that Webber came up with and found himself defending last September against his brothers and sister, against Jeffrey-bounce-Jason and David-bounce-Rachel, as they rode in a limousine to, of all places, their grandfather’s funeral.

It won’t work.

Of course it will.

Not everyone can be helped.

Of course they can.

And on it went.

“Not a discussion, a heated argument,” is how Doris Webber describes it this day, which has her wondering, once again, about how difficult it must be to grow up if the point of rising up and soaring through the air is simply to dunk a ball. She’s waiting for her oldest son to call. She has been leaving messages on his pager since he hurt himself against the Knicks, and the fact that he hasn’t called her back, “or he’ll call when he knows I’m asleep,” has her a little worried.

She explains what people see in him. “It’s hope,” she says. “It’s hope.”

She explains what she can see in him that they can’t. “It’s probably in his eyes, more than anything else. There’s a sadness to them, even though he smiles all the time. It’s intuitive, and I’m usually right on.”

She explains what are intuition is telling her now. “He’s incommunicado,” she says, “which says to me he’s not good.”

****

“You okay?” Buzz Braman asks.

No response.

“You back amongst the living?”

Nothing. Just a slight smile as Webber picks up a ball and begins throwing it against a wall. Ten times with the left hand. Ten times with the right hand. It’s two weeks after the Knicks injury. He and Braman are back at the practice facility. Time to try again. He stands just inside the foul line. He aims and shoots. One for one. Another. Two for two. Another . . .

This was supposed to happen the day before—sometimes in Webber’s life, things get a little behind schedule. The shoulder was a little sore. Maybe later, he told Braman, and he took off to do a few other things he had to get done. There was a two-hour photo shoot for an athletic wear company’s catalogue, during which the art director explained to the company, owner, “We’re doing mostly smile,” and the owner said to the art director, “Good. That’s his image,” and the photographer said to Webber, “Okay. Smile. Big smile,” and the smile Webber put on his face suggested he must be the happiest person in the world.

There was the meeting after that with a financial advisor about a long-term retirement plan, and a meeting after that with two guys with an idea to start a chain of restaurants called Chris Webber’s Sports Dream that could get as large as 20 units, could mean $400,000 over five years . . . and meanwhile, every so often, Braman, who is so devoted to basketball that he would practice with Webber at midnight if that’s what Webber wanted to do, would try to get in touch with him to see if he was coming back. 8:30 PM: No answer. “Next year, he’ll be God only knows how good,” he said before trying again. “He’ll be first team NBA at power forward, and he’ll own that for years.” 9 PM: “And he’s got the greatest pair of hands I have seen. Him and Charles Barkley. He catches everything. He’s a Venus fly trap when it comes to hands.” 9:30 PM: “Goddam, I feel so bad for him what he’s going through. But the only way to get out of the doldrums is to do some work. Do some work.” 9:50 PM: “Yo, Chris, Buzz . . . You dead? . . . Whatever you want to do, doll” Click. “He sounded like he was 10 feet under.”

So much for that day.

But 13 hours later, here he is, apparently feeling fine, and not only is he practicing hard, he is dropping shot after shot. Sometimes, in spite of all the pressures, Webber is still able to take absolute joy in what he does, and this is one of those times. Not every shot goes in, but, of the 300 or so he attempts, most do, and now he sinks 10 in a row from near the three-point line, and now he’s listening to Braman tell him, “Perfect,” and now he’s icing down the shoulder, and now he’s driving in his Mercedes to a sandwich shop near his house, and now he’s signing autographs, and now he’s just sitting and relaxing and talking, the shoulder not yet sore enough for surgery, the season not yet lost. It is a good moment, in other words, and once again he’s declaring himself blessed, but this time, instead of sounding defensive, he is trying to explain exactly why this is so.

“I’m blessed,” he says, “because I was put in all type of situations that have made me, I won’t say a good person, but a regular person.”

“I’m blessed because there were days when there was no food on the table.”

“I’m blessed because I won’t have to look at my kids and say there’s nothing to eat, like my father had to do.”

“I’m blessed because I’m more than basketball. Even if I never make a dent in helping anybody, at least I have the ideas, at least I’m working toward it, at least I’m sincere.”

“I’m blessed because I grew up with 10 guys—one who lives with me now, two are in jail, three are dead . . .”

On he goes finding blessings everywhere, even where some people might find precisely the opposite. The timeout that lost the championship in college? “That taught me patience, perseverance, and, the biggest thing, humility.”

The difficulties with Don Nelson? “I think it’s God making me stronger.”

The Bullets? The shoulder? The way he felt last year? The way he felt this year?

“I read Proverbs every day.”

And?

“I’m blessed because I’m happy,” he says. “Really.”

At which point he hears what is mother had to say, that she thinks he isn’t doing well, that she is worried about him, and for a moment, instead of being a basketball player or a role model or a savior of the Bullets or of the inner city or anything else, he is what he is: talented, conflicted, 22. He has never been one to hide his emotions, and that’s how it is now. His eyes get a little shiny. He looks away. He says, after a while, “My mother probably knows me better than anybody,” and then he says it’s not that he’s particularly sad, it’s just that, so far, there’s something about life he’s been unable to figure out.

“I want to know how to live,” is what he says. “Sometimes I feel guilty about what I have. Why me? Why did God pick me? That’s what I ask myself. How do I live in peace with myself?”