[The Miami Heat sat on the 12th pick in the 1992 NBA Draft. Common sense told Heat coach Kevin Loughery that no high-impact players would remain on the draft board by Miami’s selection. He was wrong Still available was USC’s All-Everything southpaw shooting guard Harold Miner, a.k.a., Baby Jordan, as in Michael. “We were unbelievably surprised,” said Loughery, who’d heard that the uber-athletic Miner was a lock for Denver at the fifth pick. Common sense then told Loughery not to think too hard about why Miner had slipped from five to a question mark. Just take him. “If he’s as good as we think he is, if he can live up to the expectations” Loughery said afterwards, “he can be an impact player.”

Loughery’s selection left the reporters in Miami to do some quick digging into Miner. The portrait that emerged was of a likeable, but quirky, young man who loved the game and wasn’t bothered by gravity. Or, reading between the lines: Who knows what the future would hold for Miner. He might be the next Jordan. Or he might be out of the league soon after his first three-year contract.

The latter pretty much would be the case. By the 1994-95 season, Miner was a spot starter. But for the most part, he backed up the tall-and-talented Billy Owens and faced the same question from the Heat brass: “We need to find out if Harold can contribute and play in the NBA.” Rather than wait any longer for the answer, Miami shipped Miner to Cleveland. The Cavs quickly traded him to Toronto. The Raptors then cut him right out of the league, Baby Jordan no more. Too bad. Miner was a player and belonged in the league much longer than that, in my humble opinion.

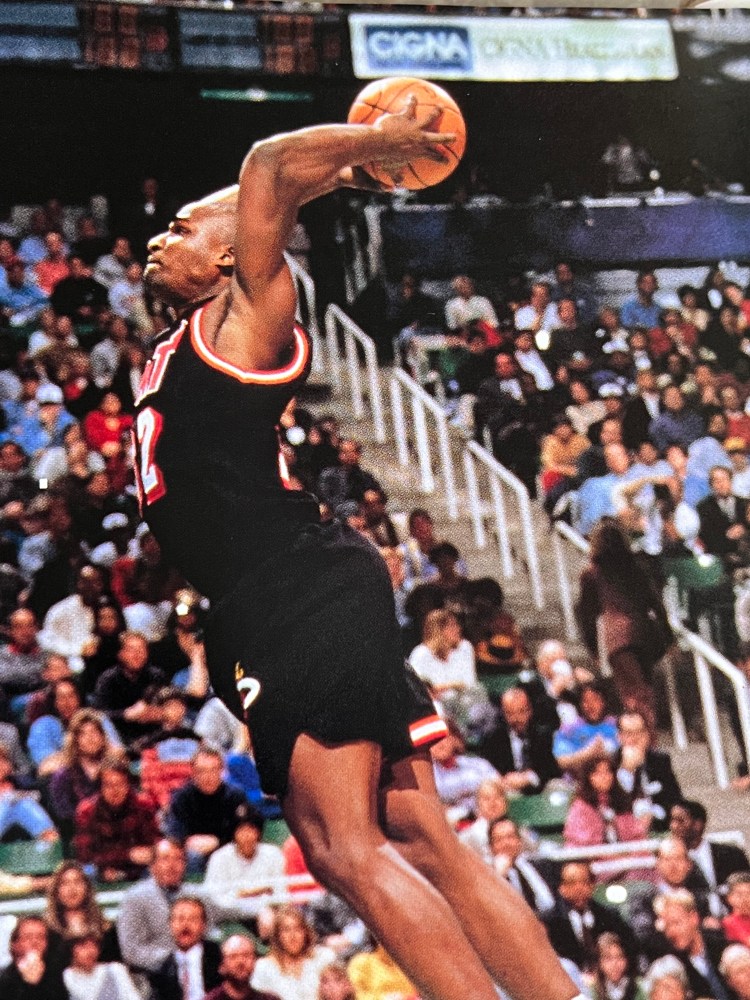

In the article that follows, from the January 1994 issue of Rip City Magazine, we catch up with Miner in his second season with the Heat. The portrait that emerges is of a college star who needs time to master the pro game. But the high expectations that came with being miscast as the next Jordan and winning the NBA Slam-Dunk Competition (he would win it twice in his three complete NBA seasons) would make his learning curve too steep and his critics too impatient. At the keyboard is the magazine’s then-editor-in-chief David Higdon.]

****

It’s not easy getting a handle—much less a hand—on quick-moving Harold Miner. The second-year Miami Heat guard is a bundle of contradictions, a soft-spoken kid from the trash-talking Los Angeles playgrounds who prefers jazz to rap, loves lasagna and isn’t anywhere near the 6-feet-5 at which he’s listed. Miner’s a strutting, spinning show-off on the hardwood, yet shy and reticent when he’s not dunking, shooting, or rubbing a basketball, the last being his quirky trademark at the free-throw line.

He entered the NBA nicknamed Baby Jordan, then proceeded to spend most of his rookie season riding pine, the only Heat player on the team’s less than illustrious 1992-93 roster who did not start a game. Still, he probably received more national attention than any other teammate thanks to a slick TV commercial for Nike and his winning performance at the 1993 Gatorade Slam Dunk championship. Miner even has his coach, Kevin Loughery, spinning round and round. “I’ve been a big critic of Harold Miner at times,” Loughery said prior to this season, “but he’s made a 360 in his intensity level.”

Loughery meant 180, but who’s measuring? He was so tickled to have Miner show up for camp in shape this season that he was talking in circles. Nearly a decade earlier, Loughery coached a talented rookie in Chicago. A fellow by the name of Michael Jordan. As a rookie last season, Baby Jordan arrived with too much baby fat, then proceeded to demonstrate why the transition from college hoops to NBA ball isn’t as easy as the likes of Shaquille O’Neal make it seem.

“Last year, he showed up in terrible shape and had no concept of the NBA game,” says former coach Jack Ramsay, now the Heat’s TV analyst. “He didn’t run the floor, he didn’t defend, he didn’t work without the ball, and he couldn’t get his shot off.”

Is that all? What he did do, however, was learn. On the bus trips last season, he would slide behind Ramsay and badger him with questions about NBA legends like Jordan, Oscar Robertson, and Jerry West, querying Dr. Jack on how they played, the way they moved, and what they did to improve their games.

Miner has an extensive videotape collection that includes footage of the Doctor, not Marcus Welby, M.D.; of Magic, not the Magical Mystery Tour. The home video collection of NBA greats would be even more impressive if Miner weren’t such a doggone friendly fellow. “I’ve loaned a lot of the tapes out,” he says, “but if I ever get them all together again . . .”

If he ever gets his game together, he may need to leave more room on the shelf for tapes of himself. Early signs this season indicate that he’s on his way. “Harold’s worked extremely hard at developing his natural talent,” says Portland’s Clyde Drexler, who went through similar growing pains as a rookie. “I think he’s an extremely promising young player.”

After leaving Miami last season “totally dissatisfied,” according to Ramsay, with his rookie performance, Miner spent the summer in California training with UCLA assistant track coach and former Olympian, John Smith, who worked on Miner’s speed, stamina, and running form. Miner’s former college coach, USC’s George Raveling, helped him polish his basketball skills. He also spent three days practicing and reviewing game films with Loughery in Los Angeles and played in Europe with a team of NBA players.

The result? A more intense, controlled, and stronger shooting guard who outplayed incumbent Brian Shaw in training camp to earn a starting position. He’s added a few more moves to the explosive first step that enabled him to average 10.3 points a game last season as a bench player and has demonstrated a commitment to using his rock-solid body—and mind—on defense. “One thing I said to him at the end of the season, ‘When you’re on defense, you’re thinking about offense,’” says Heat scouting coordinator Tony Florentino. “And he smiled. He knew I was right.”

The 22-year-old Miner grew up a short bike ride away from the Los Angeles Lakers’ arena in Inglewood. He and his pals used to sneak into the Forum practically every night, entering the building two hours before game time, holing up in the men’s bathroom stalls and then sliding back out after the crowd started settling in their seats. When he wasn’t watching hoops, he was playing it, cruising from playground to playground, looking for a game whether it was a five-on-five, one-on-one, or Harold vs. The Rim, working on the moves and dunks which would impress his peers.

“Playing playground ball is basically all talent,” says Miner. “You have to show what you can do and try to embarrass guys. You need to earn their respect.”

He immersed himself in the game, avoiding the pitfalls in the rough neighborhood that felled several of his friends. Miner recalls one night as a youngster, when he looked outside his bedroom window and saw someone crouched behind a bush in his backyard. Then the man stood up and began firing a gun. “I had to take cover, get low,” recalls Miner. “That happened a lot. There were dealers all over the street. But I stayed away from drugs and drinking and gangs and all that stuff. I wanted to make it to the pros.”

After a high-profile high school career in Inglewood, Miner chose to remain in the area to attend USC and play for Raveling. Miner became the second player in PAC-10 history (after Lew Alcindor) to score more than 2,000 career points in three seasons. He’s USC’s all-time leader in points and scoring average (23.5 points per game).

“My brother (Cameron) has committed to USC, and one of the reasons is because of what Harold was able to do there,” said former UCLA and now NBA star Tracy Murray, who often faced Miner in high school and college. “Even right now, Coach Raveling is helping Harold in any way he can.”

Miner was a consensus All-America player his junior season, after which he entered the NBA Draft and was selected No. 12 by the Heat. Many felt he would go higher, but the same traits which he displayed last season—mainly an inability to play team ball—scared off several earlier suitors.

Miner’s flashy play, however, made Nike drool and turned him into a big hit with Heat fans. For example, he scored 70 points in one three-game stretch last season. He also matched a franchise record for consecutive points scored in a game when he rattled of 14 straight fourth-quarter points in a game against Philadelphia. Instant offense, however, doesn’t necessarily translate into consistent output, which is why he spent so much time working on his deficiencies during the offseason.

“Everybody says between the first and second year, that’s the most-important time,” says Miner. “It’s more mental than anything else.”

At the 1993 All-Star Game, Miner impressed two of his former idols, Julius “Dr. J” Erving and Connie Hawkins, who were judges at the slam dunk contest. Afterwards, Dr. J told reporters that the thing he liked most about Miner wasn’t his dazzling dunks, but his calm, cool personality.

The same characteristics drew the attention of Pistons guard Joe Dumars. “He’s a great kid,” says Dumars. “Anytime I see someone with those elements, I’m drawn to that. We mostly talked about how to carry yourself and how to handle yourself with grace.”

Cool Harold has proven that he has no problem turning up the heat on the basketball court. When he learns how to keep the fire burning, to bring the smoldering style of his favorite soft jazz musicians like Grover Washington, Jr. to the basketball court, he’ll become more than just a sideshow at future NBA All-Star games.