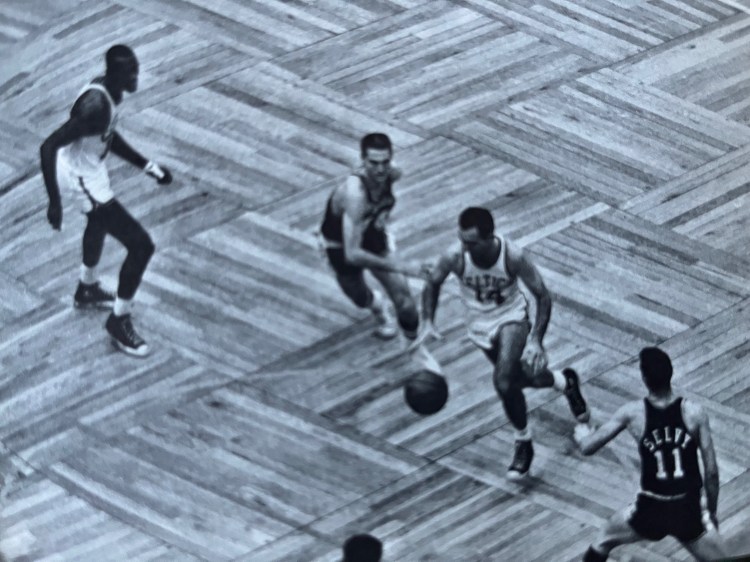

[In 1962, the Los Angeles Lakers and Boston Celtics faced off in the NBA Finals. Game Three, played in the L.A. Sports Arena, went all the way down to the wire. With three seconds left, the Lakers’ Jerry West sank two foul shots to knot the score at 115. Time out, Celtics, to either sink the game-winner or move into overtime. As the crowd roared and Boston guard Sam Jones inbounded the ball at halfcourt to teammate Bob Cousy, West shuffled into the passing lane. “I deflected the ball,” said West afterwards, “and I think it hit Cousy. There it was, and I went for the basket” a full 45 feet away. West dropped in his dramatic game-winning lay-up, followed by the blare of the final buzzer and the swarm of fans onto the court to celebrate the Lakers’ two-to-one advantage in the best of seven series.

What follows is a syndicated newspaper column from the great Jim Murray of the L.A. Times. It was prompted by a young fan who stormed the court after the final buzzer to “take a swipe at him.” This didn’t sit well with Murray, who used the moment as his launching point to sing the praises of Cousy as he neared the end of his brilliant NBA career. Though Murray’s encomium is a little rich in places, his sentiments are real and capture well Cousy’s legend and popularity in the early 1960s. Most of all, Murray is always a fun read. His column ran in the L.A. Times on April 12, 1962.]

****

There are some things that should not happen, and one of them is that Bob Cousy should never have to walk off a basketball court with tears in his eyes. And the young man, who ran out on the court to take a swipe at him as he did the other night should be taken to the woodshed forthwith.

There were more than 15,000 people in the L.A. Sports Arena two nights this week. If there had been room, that could’ve been 20,000. I don’t know of anybody who can take a deeper bow over this state of affairs than Robert Joseph Cousy.

At his age and status in life, you might expect to walk up to Cousy after he had lost a hard game, ask him if it hurt, and get a wisecrack in reply, “Only when I laugh.” But Cousy’s approach to basketball—or anything else—has never been flippant. Bob Cousy is one of the finest athletes and finest gentleman ever to grace any professional sport. The really magnificent thing is that after 12 years of gallops up and down the hardwood floor, a confused mélange of arenas, and crowds and dusty buses, and 100 nights a year of hearing, “Cousy, you’re a bum!” Bob Cousy not only still cares he cries when he loses.

He was still a little sheepish as I braced him in his dressing room the other night, not over the tears but over the fact he whirled on his tormenter who was beating him on the back. “I thought it was a man, and I felt bad when I turned and it was just a worked-up kid.”

Before Bob Cousy, professional basketball had all the class of a traveling band of snake-oil hucksters. Franchises were jerked out from under the league. The Pistons were in Fort Wayne one part of the season and some other place—or two other places—the rest of it. The players moved by bus or creaky old airplanes that Eddie Rickenbacker’s Flying Circus wouldn’t throw their goggles in. The crowds were just guys waiting for the pool rooms to open.

Cousy brought the electrifying drama of the dribble behind the back, the backward pass, the all-court pass off the dribble, and any one of the dozen feats of legerdemain that not only hadn’t been thought of as possible but hadn’t even been thought of, period. For the first time in history, when someone referred to a “dribbling foot,” he meant it as a compliment.

Cousy doesn’t even look like a basketball player. He looks like what he also is, an insurance agent. He was even cut from the high school team once. His legs are too heavy. He’s what the mariners would call “beamy.” But basically, his trouble is that he’s built too close to the floor. At 6-feet-1 on the skyline of professional basketball, he’s a shack.

But there’s little doubt the majestic poise of the Boston Celtics derives in large part from the presence of Cousy. He revived the science of playmaking just at a time when it seemed the pivot man and the overworked pituitary would reduce the game to an endless comedic vaudeville—when a player’s only future was stooge for the Globetrotters.

He was as canny as he was good. He led the fastbreak like the lead kid out the door on the last day of school. On court, he had a field of vision like a haddock. The Celt player who was daydreaming was liable to find a basketball sticking in his ear from a Cousy pass thrown while Bob had his back to the target. He specialized in whistling a pass close enough to the ears of a rival and make him flinch enough to open a path for a Cousy drive-up.

Many of the Cousy techniques are standard today. They were revolutionary when Cousy tried them. The business of showing a defender the ball in one hand, like a shill flashing a pea under a walnut, then switching it quickly to the other hand for a layup has flowered under Baylor. But it may have been planted under Cousy.

Basketball is an endless search for the “open” man today. An orthodox pass will never find him. Cousy has practiced the no-look feed so expertly, there have been movements to frisk him for mirrors.

The game will be poorer without Bob Cousy. He’s the son of French immigrants, whose father had to give up a baronial farm after the Kaiser burned it down for a taxicab job in New York. But Bob is genial and approachable, and a man who has given unselfish hours to the promotion, not of Bob Cousy, but of the sport generally.

He is decent to the core. His own speech impediment, the “r’s” come out “w’s,” which gave the gagsters a field day with his “Roman Meal Bread” commercials, may be rooted in the fact he had a two-language communication problem at home. But it made him aware of the shyness of people handicapped in the world. His college thesis was “The Persecution of Minority Groups,” and he lived up to its high sound in Raleigh, N.C., one year when a hotel turned down his Black teammate, Chuck Cooper. Cooz got tears in his eyes then too—from anger—called for his bag and rode a sleeper back to New York with Cooper.

As elder statesman of the game, Cooz gets certain privilege—a $35,000 salary, dressing in the head coach’s office. But among them should be the right to walk off the court dry-eyed with head held high—to the accompaniment of cheers, not punches in the back.