[Years ago, I interviewed the late-Howie Garfinkel about the origins of his influential Five Star Basketball Camp. Garf told me that Five Star nearly went bust after its first summer. But he and his now-lone partner hung in there and hustled during the next school year to coax enough kids to sign up for Five Star and keep it going. The camp remained very much up in the air as summer approached until an obscure New Jersey high school coach one day greeted Garf with a thick envelope full of applications to attend the camp. The coach: Hubie Brown.

Brown, the Five Star savior, quickly became a popular camp instructor and, paraphrasing Garf, was a born, charismatic teacher with a deep understanding of the game and an uncanny ability to effectively communicate its X’s and O’s. Today, now in his 80s, Brown continues to teach the game as an NBA television analyst, his familiar Jersey accent, though thinner with age, still delivers very much on point.

But back in the early 1990s, Brown briefly allowed his name to be used on an annual basketball magazine. It was called Hubie Brown’s Pro Basketball Annual (“For the Serious Fan”). Brown even penned an article or two, including the one below from the 1993-94 edition. His article goes in a lot of directions, but it’s interesting just the same. It was penned before the Colangelo Committee got a hold of the pro game and created today’s NBA with its zone defenses and emphasis on scoring buckets.

The article includes a pull-out checklist for winners, which I’ll quickly summarize here. On offense: Shoot 30 or more free throws; grab 15 or more offensive rebounds; convert 60 percent of fastbreak opportunities; and get high-percentage shots for your three best scorers. On defense: Force 20 turnovers; make 10 steals; make seven deflections each quarter; block five to seven shots; limit second-chance shots to 15 or fewer; limit fastbreak conversions to 50 percent. And that’s all per game. Here’s the rest of Brown’s thoughts on how to watch the NBA.]

****

The biggest misconception that most people have when they watch an NBA game is that it’s unorganized and that they’re playing by feel. You’ve got to remember a few things here. There is basketball that’s played at the elementary, junior high, high school, and college levels. They’re all played at rim level, at 10 feet. Then there’s this game played a foot above the rim, at the top of the box. It’s called RollerBall

That’s the NBA. And you cannot use the same equations, the same logic, that you want to use at the lower levels. The rules are different; the athletes are bigger, stronger, and quicker; and the game is played under duress.

During the regular season, there are a minimum of five fouls on every play, and none will be called. At playoff time, there will be a minimum of 10. If a player can’t deal with physical punishment, if he lacks offensive structure and is limited by his offensive talents, he’ll never excel. That’s why so many All-Americans are home after three years. This is a different game. This is for the purist, not for the faint of heart.

You have to understand these aspects of RollerBall:

- It’s played on a wider lane, 16 feet versus 12;

- The three-point line is deeper, 23 feet, 9 inches;

- The game is longer, 48 minutes versus 40;

- You’re allowed more fouls. You’re shooting the bonus free throws on the fifth foul of each quarter, which dictates strategy;

- Smart teams always take advantage of the penalty situation. There are more timeouts—seven compared with five in college—plus one 20-second timeout per half. You can delay a game once and get away with a warning before the technical foul;

- No zone defenses. Or let’s say, no legalized zones as we know them. You cannot trap a player unless he has the basketball;

- The 24-second clock changes the game. It necessitates organization offensively, and it rewards the great defenses. The referees will rarely decide the fate of the game by a call in traffic. They want the players to win or lose the game. This is a cardinal rule. If no one died on the play, don’t ask for a call, especially at playoff time.

When you’re watching a game, look for situations and how quickly those situations are recognized. Like when the ball is being taken out of bounds on the sideline on the offensive end. The most-dangerous player is the man out of bounds. Most people will play him, but once the ball is passed inbounds, the defense has a tendency to lose sight of where he’s going.

Another situation: End of the game, do you play the man out of bounds? If you put a man on his passing hand, you can eliminate two of the three passing areas: the close corner and a direct pass into the post. You’re going to give up the pass to the top of the circle. By not defending the passer, you give him perfect vision, and his percentage increases for completing the pass.

Be sure to watch the actions of the defense. They will probably be the most telling. When good teams play great defensive teams, the first two offensive options will probably be taken away. Now you’re forced into your third or fourth options, and they’d better be effective, because the 24-second clock is winding down and it becomes difficult to secure a high-percentage shot.

Let’s go inside the game:

OFFENSE:

Free-lance? Some people think that they just roll out the ball and let ‘em play. Forget it. If an NBA team is unorganized offensively, it can be negated by the size, quickness, and shot-blocking ability of an average defense. I had seven assistants who became head coaches, six of whom came from the college level. And at the end of the first week of training camp double-sessions, every one to the man was shocked by the defensive talent and the amount of pressure applied on the shot release. At this level, the players are so talented that a half-inch opening equals two points in your face.

Spacing. Great offense is dictated by proper spacing. When you watch the outstanding offensive teams, they’ll have two or three men on one side of the floor and two or three opposite. The movement on the opposite side is designed not only to free up an individual for a shot, but to keep the defense busy so that it cannot rotate and help out in what we call a “red” situation, where a player is in a dangerous shooting zone.

The Phoenix Suns use one or two options and then rely on their penetration to develop options, three, four, and five. It all depends on spacing; they get the majority of their three-point shots off of penetration and kick-outs. Few teams can play this way, because they don’t have a Kevin Johnson or a Charles Barkley, who demand double-teaming once the ball penetrates below the foul line.

Mismatches. Passing is becoming a lost art. Sometimes, as I watch games, the IQ of the game is missing. If I, as a dribbler, create a switch on defense and suddenly my 6-foot defender is replaced by a 6-feet-10 defender, I should realize that my 6-feet-10 offensive player, rolling to the basket, has a mismatch. I must keep my dribble, create proper spacing, and feed the post, because there is no way, in the majority of cases, that the defender who is giving away six to 10 inches can defend my teammate. It takes recognition, creating space and the ability to deliver the pass. Never pass until the post-up player calls for the ball.

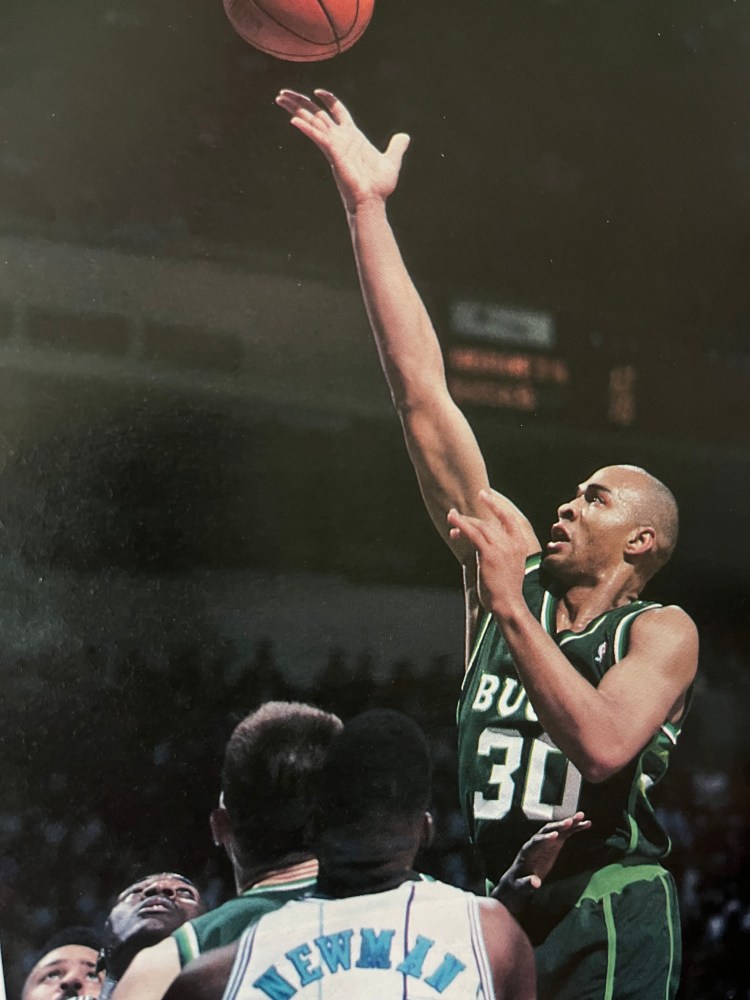

Isolations. You can exploit isolations only when you have a player who blends outstanding dribbling ability with a quick first step and is also a dangerous outside threat. Once penetration begins, the outstanding players can accept double- or triple-teaming and either deliver the pass to the free man below the foul line or, because of natural talent, split the defense and create the high-percentage shot for themselves. The ultimate isolation player can do all of the above, plus has the ability to draw the foul if the shot is missed and shoot a high percentage at the foul line. He probably is your No. 1 go-to player when the game is on the line.

Screens. The screen-and-roll has been there since Moses parted the sea. It’s still the most-effective play in basketball because there’s a chance for success by both the screener and the man with the ball. The premier screen-and-roll teams are New York, Detroit, Portland, and Chicago. The staggered screen, which came in during the 1980s, is more difficult to defend than the screen-down, the double-screen, or the stack. I maintain that the staggered screen is the toughest thing for a defensive player to fight through, because it can include two or three screens and two big men will be involved in the screening. Players will fight through the first and second screens, but nobody likes to get hit three times at this level because of the size of the players. The staggered screen has forced defenses to become far more creative in their coverages. We are now seeing more switching and teams not worrying about mismatches because the shot clock is winding down.

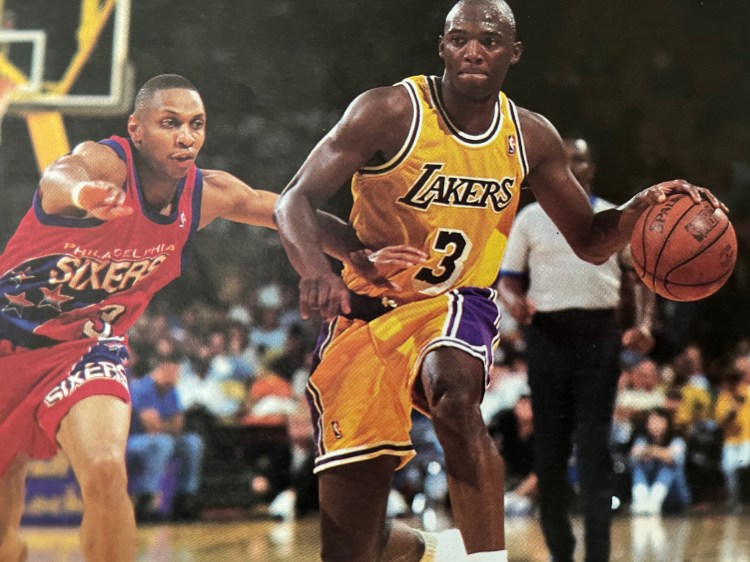

Breaking Down the Defense. A transition or fastbreak team can rely on the dribbling ability of its guards to make it happen—create situations that lead to one-on-ones on a quick roll to the basket. Or managing to get a shoulder ahead on the defensive man and draw another defender as he drives toward the lane. When this happens, the defense is scrambling. Great dribblers give you that advantage, but what sets the elite players apart is the ability to make a pass in traffic, score with either hand, or get fouled and convert free throws. Once you break the foul line, you have only a hundredth of a second to make the right decision. In the NBA, that’s only a handful of guys.

Secondary Break. In the transition game—which comes from a missed shot, block, deflection, or steal—teams flow into a two- or three-man break. As the defense recovers, the ballhandler can either slow the break or back it out and call a play. But you also get a trailer as determined in practice, so that a quick-hitting pass will initiate movement of all five guys. A defensive mismatch can be exploited. The initial break has stopped, but you can still score out of an unsettled situation.

Alley-Oop. It’s incredibly dangerous at the NBA level because of the size of the defenders. The collisions are way above rim level, and you have the threat of a head hitting the backboard. When the collision occurs, the drop to the floor is eight to 10 feet with no pads. You could hit the floor and then crash into the stanchion, hit a cameraman, or suffer the worst possible sprained ankle coming down on another player’s foot. These injuries take weeks to return from, never mind a hundred other injuries that could occur. If this is a playoff game, you know you’re ending up in the first row of the stands. It might look pretty, but you could lose a star player.

End-Of-Quarter. The majority of teams, in milking the clock, will usually wait until there are six or seven seconds remaining. The penetration will begin, and you can usually get one shot and a potential offensive rebound before the clock runs out. The reason you wait this long is so that the opposition does not get a chance to rebound the miss and get off a long shot or, if it’s in the last two minutes of the fourth quarter, call time, move the ball to halfcourt, and have an extra chance.

Inbounds Plays. On the baseline in front of the basket, the defense must always protect against the pass to the front of the rim. That’s for openers. Number two, the offense will try to get the defense to switch a big man onto the small man and create a quick post-up situation. Third, if there is one second on the clock, they could run a lob, using three staggered screens. Not only are they looking for the man coming off the screens, they’re looking for any of the three screeners going to the basket. They are hoping for two defenders to end up on one offensive player. It’s more physical on the baseline, because the screens are quick, and you’re working in a smaller area.

The Three-Pointer. It’s pure excitement, the ability to score points quickly in fewer shot attempts. It strikes a dagger into the heart of the good defensive teams, especially discouraging to the player who is in the face of a great shooter. The easiest way to get a three-point shot without running a play is in the open floor on the break (because there are no designated defenders) or when the ball is penetrated into the foul-line area, stopped, turned around, and then thrown back out to a three-point shooter.

The reason? From the time you start playing basketball, you are told, in a defensive situation, to get to the level, or the same plane, as the ball. If the ball is below you, come back in and help. All great defenses converge back into the ball. So the three point shot is contradictory to what is drilled into us in defensive philosophy—get below the ball. There are other ways to create the shot without using a set play. One is to dribble-weave the ball, and as you receive the ball, just step back. Another easy way is coming off the screen-and-roll; screen and step back, like Detroit’s Bill Laimbeer has been doing for years.

Last-Minute Comebacks. This, to me, is coaching (clock management). If you’re down five points and inside 15 seconds, get the two first, because in most circumstances, the defensive team is told not to foul. If you post up or drive toward the basket, they’ll invariably give you the quick score. Many coaches have a side out-of-bounds play going to the basket that will result in a score within two to four seconds. As soon as you score, apply your full-court press—total deny—and if you make your steal, now you’re looking for your three. If not, foul and play clock management. If you take the three first and miss, in the majority of cases, you foul and now the game goes to six or seven. I realize in some instances, you hit the three, you press, you make the steal, and you score your two. But we’re talking 90-10 here in percentages, at all levels of basketball.

There are exceptions. If you inbound the ball, and they give you the wide-open three, of course you take it. But this will come down to the philosophy of the coach and how much faith he has in his defense to get the ball back. In the NBA, if you score your two and they call timeout, they can move the ball to halfcourt, but they still have to inbound it. And once again, you’re into clock management. You’re trying to give your team as many chances as possible to win the game. It’s easy to shoot the three, miss it, and lose the game: “Hey, we were down five.” It’s harder to do what we’re describing because it takes team discipline, practice, and faith in your defense.

The Passing Game. You also have a number of teams playing the passing game, which you also see at the high school and the college levels. There are different styles—single post, double-post, high-low post, middle open. This is taught at every level, and some run it in the NBA. No passing-game team has ever gotten to the NBA Finals because in a seven-game series, it’s easy to eliminate the routes and force the offensive team to stay on the perimeter.

DEFENSE:

The Best: Over the 82 games of last season, the Knicks were the best halfcourt defensive team in basketball. They backed it up, allowing only 95.4 points per game, led the league in overall rebounding and held opponents under 100 points 52 times.

But in my opinion, when healthy and rested, the NBA’s best 94-foot defensive team is the Chicago Bulls. They’re pressing full-court with Horace Grant and the point guard on the first trap. Then you have your two off-ball passing-lane defenders—Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen—ranked first and 10th in the league in steals, playing the next pass. They back this up with an excellent half-court trap and a dynamite top of the circle-to-basket defense, anchored with Jordan as the designated double-teamer on all post-up plays.

Guarding the Greats. No defensive player is going to stop a great offensive player one-on-one. The defender needs help once the pass is received and the offensive player starts penetration with the dribble. The offensive player always knows when he’s going to elevate for the shot. The element of surprise gives him the advantage. Now, where will he release the shot? On the way up? At the top of his jump? Or on the way down? The true superstars have three release areas, while still shooting a high percentage—that’s why they’re superstars.

Double-Teams. The reason teams double-team is to stop a great offensive player from reaching a high-percentage shooting area. You are looking to cause intimidation, force a lower percentage, create a turnover, or use the 24-second clock by causing the offense to make an extra pass.

Offensive Fouls. At the junior high, high school, and college levels, you can get that particular call. But in the NBA, there’s an unmarked area—it’s safe to say it’s below the dotted line in the paint—where charging won’t be called. Because of the players’ aerial acrobatics, referees don’t want to encourage undercutting and risk serious injury to the marquee players. In many instances, it’s impossible to call anyway, once the player goes airborne.

The Shot Goes Up. The poor transition defensive teams usually get caught sending four players to the offensive board, leaving just one player retreating for defensive court balance. The excellent transition defensive teams, in most situations, sent three to the offensive board and rotate two players back on defense, preferably two guards. An exception might be a guard and a small forward. In some cases when the shot goes up, the philosophy will be to send two big men to the board and leave both guards and a forward back. In today’s basketball, you must be able to negate the transition game if you are going to win consistently. Defense begins with offensive rebounding first, challenging the outlet pass second, and then retreating two or three men into a match-up situation.

COACHING:

Impact: A coach’s job begins with his organizational skills—scouting reports, how they are relayed to the players, practice-time management, and the rules that govern the team. The second phase is offensive and defensive philosophies. There is a smorgasbord of styles of play. The coach should stay within his own personality and teach what he knows the best. In order to implement all this, you need an inner discipline. By this, I mean a respect for the coach and a discipline for the team that allows the offenses and defenses to be run with five people working on a string, that they can all rely on the physical efforts of their teammates under pressure. Good coaches always try to surround themselves with good people, because good people will always outwork people with potential but who are not coachable. The final—and most important—item for a coach is that he has a style. Whether it’s a band, whether it’s a salesman, a coach, a teacher in a classroom, they all have a style, and all the great teams are remembered by their style.

Calling Plays. Plays are called verbally. But you worry about crowd noise, so they are also given with a hand signal, by using numbers or by a brush of a different part of the anatomy. Some are given by using a sign off the bench, like with cards. Some plays are run by the direction of a pass, because the set may have been predetermined. So the play is run by either the direction of the pass or the direction of the dribble.

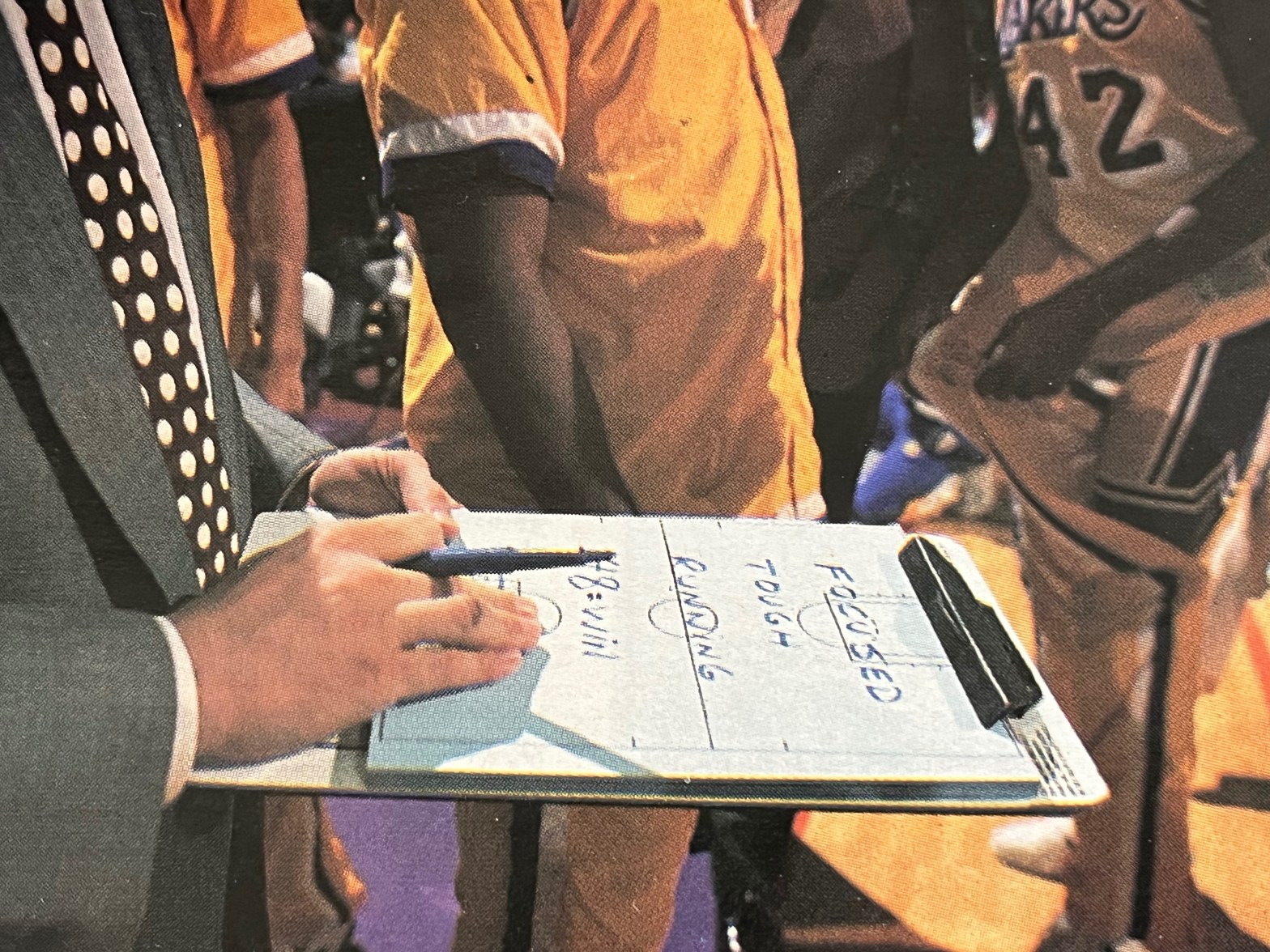

Timeouts. When a timeout is called, you like to quickly check the statistics that are kept by your assistant coaches—which plays are working, what play you face to inbound the ball. You also ask for quick input on matchups or situations. When you address the team, never talk for the full time without using chalk on the floor, a miniature court with magnets, a marker pen. Because under the pressure of the moment, the coach’s job is to eliminate human error. Remember that people retain what they see at a much higher rate, like 83 percent compared to 11 percent of what they hear. Even though it is repetitious, you still show them, relying on site and memory versus words and memory. Before they leave the huddle, they should all know the play, the number of fouls you have to give, and how many timeouts they have left. That’s a lot, but when you go into that huddle, it’s the coach’s job to understand the pressure of the moment and try to eliminate human error.

Working the Refs. The most-overrated statement you hear used is that the coach really wanted that technical foul. The majority of coaches are shocked when the technical call is made against him. I was in coaching 30 years and was asked to leave many times after two technicals, and I never once wanted to depart, no matter how bad the situation was. It’s so overrated—“He took that technical to change the course of the tempo of the game.”

You go through eight exhibition games and 82 games in the regular season. That’s 90 games for starters, and then the playoffs. You’ve got to understand the referees have personalities. They are human, and if you’re going to bicker, you must always be prepared for a shock. Since your personality is dictated by your biorhythms, how can you anticipate where this man is coming from on a day-to-day basis? The referees are in a tough spot because every night, there are five fouls on every play. What’s a foul tonight? It varies from game to game.

Foul Trouble. You are relying on the ability of your player not to pick up the next foul, especially if he gets two early in the first quarter. You keep him in his regular rotation based on his maturity and his reputation. You’re hoping he doesn’t pick up a ticky-tack foul. I don’t think there is any way, other than not playing a man, to keep him out of trouble. You might go to a zone to protect a player. Or you might ask him not to challenge a shooter.

Bill Cartwright always used to get two fouls quickly in the first quarter when we were with the Knicks, and I’d take him out. Finally, he came to me one day and said, “Hubie, if you leave me in, I’ll never get my third in my regular rotation.” And you know what? I left him in, the first time I ever did that with any player. And he’d never get that third foul early, and he played with more confidence. He’d get rid of that nervous energy.

Points Don’t Matter. Coaches put together offenses piecemeal. What they enjoy teaching is what has been successful for them as player or coach through the years. They must look at their talent, knowing whatever they do has to be successful against the NBA’s best defensive teams. If your plays work over 82 games against the league’s best defensive teams, they will work at playoff time. Many coaches fall into a comfort zone, saying, “We average XX amount of points a year.” Well, the leading scoring team in the NBA has not won a championship since 1975, and that was Golden State with Rick Barry and company. So scoring a lot of points is not an accurate barometer for a team’s chance to win the NBA championship.

At playoff time, the teams that get eliminated in the first and second rounds invariably cannot score the same number of points they scored during the regular season, and it is a major drop-off, not a small one.