[No need for a long windup to introduce this article. It’s a profile of Lenny Wilkens late in his NBA career while toiling with the Cleveland Cavaliers. The story, written by the legendary Pete Axthelm, ran in the May 1973 issue of SPORT Magazine. Enjoy!]

****

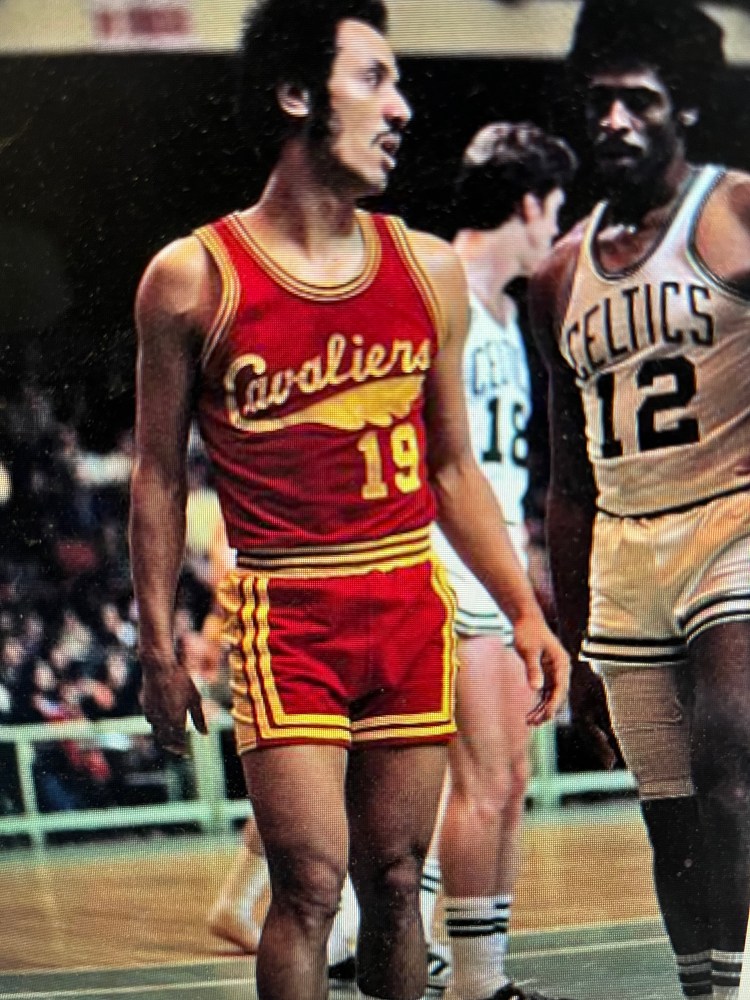

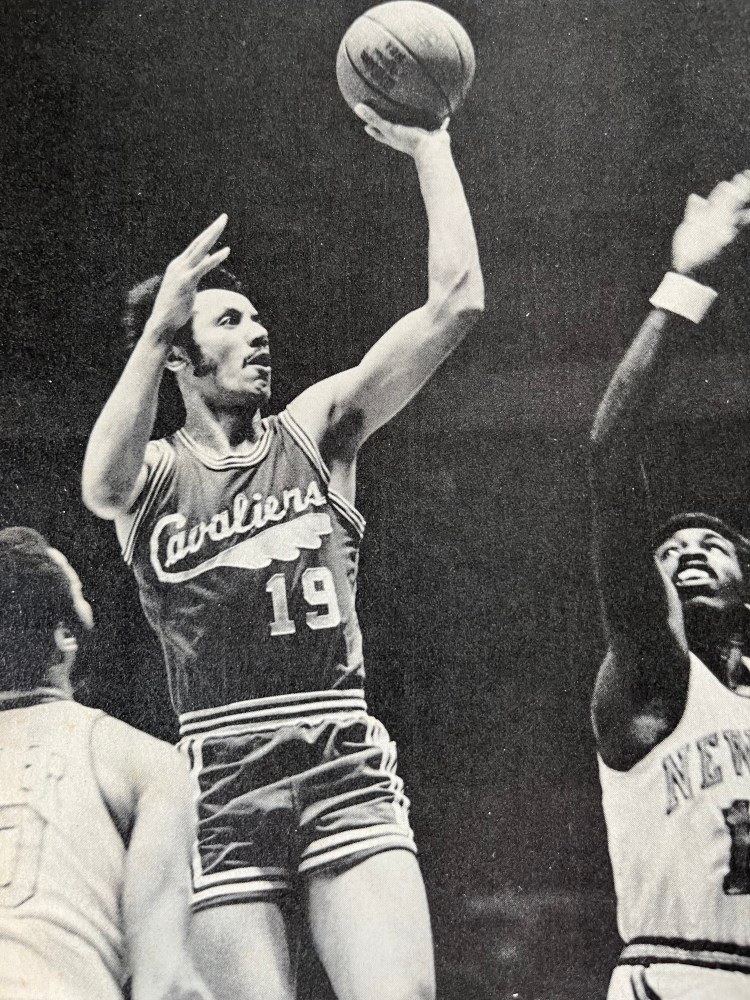

Lenny Wilkens plays with a delicate mixture of control and reckless abandon. He surveys the entire court with a cool, unperspiring gaze, dictating the tempo and directing the flow of the action, yet always ready to hurl his 6-feet-1 body into swarms of bigger men in a bruising drive to the basket. He knows just what is happening around him and precisely when to initiate a sudden darting move that makes things happen. He has no classic jump shot, and few of the breath-grabbing gyrations that pro basketball fans expect of their star backcourt men. Lenny Wilkens’ game is a subtler art form, built on sly quickness, courage, and, most of all, brains.

The style was born more than two decades ago, alongside the tattered wire fences that surround Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant playgrounds, where, as a shy and skinny teenager, Wilkens would wait with other marginal athletes, watching, learning, and always hoping that the flashier neighborhood stars might invite him to fill out a pickup game. It was a pressure-filled situation, in which one misplay might condemn him to the sidelines for another long, hot afternoon; and failure came often to Wilkens.

When he tried out for the Boys High team as a freshman, he was ranked 15th among the 15 players, and he quit. He didn’t join the squad until his final semester of high school; then he was overshadowed by teammate Tommie Davis, the baseball player. When Lenny graduated, there were no scholarship offers until Providence coach Joe Mullaney found Wilkens playing Catholic Youth Organization ball. At Providence, Wilkens blossomed, but still, when he joined his first pro team, the St. Louis Hawks, he was certain he would be undersized and unwanted. Years later, returning to the playgrounds where it all began, Lenny would allow himself a quiet smile, when old friends told him, “You fooled us. We watched you around here all that time, and we never even knew we had a ballplayer.”

At the age of 35, after 13 seasons in the National Basketball Association, Lenny Wilkens remains one of the most consistent and effective ballplayers in the sport. He has played for three teams, and coached one of them, handling every task with understated, but remarkable skill. He is among the 20 highest scorers in pro history, and only three men—Bob Cousy, Oscar Robertson, and Guy Rodgers—have been credited with more assists. He is now providing desperately needed leadership and cohesion to the Cleveland Cavaliers, helping a three-year-old expansion team toward respectability.

Yet, even now, there are those who may be fooled by Wilkens’ low-key style—or by the handful of detractors who have questioned his value to his teams. For as well as he has performed throughout his career, Wilkens has sometimes seemed haunted by trouble; circumstances have often cast this soft-spoken, strong-willed man in the role of a controversial and misunderstood character.

In his early years in St. Louis, he was the model of unselfishness as the playmaker for the Hawks’ more-publicized stars. But when dissension rent the team in the mid-1960s, he was fingered as one of the culprits; and when the Hawks’ new owners in Atlanta began trying to hold down salaries, Wilkens was the first to be offered a pay cut—and traded away. As coach of the Seattle SuperSonics, he nursed a struggling young team, to the point, where it had the sixth-best record in the entire NBA; but he was publicly second-guessed and then relieved of his coaching duties. Finally, when the Sonics traded him to Cleveland last fall, the Seattle management intimated that, as a mere player, Wilkens might have been a disruptive force, seeking to undermine the coach who had replaced him. To an athlete who had devoted an entire career to developing himself as a team player, that was the unkindest cut of all.

“Sometimes, I ask myself, ‘Why me?’” Wilkens admits. “Why do I end up in the middle of all this stuff? I’m not the type of person to cause problems. People who know me know that I’d do anything to help my club. At least, I think they should know that. Then, the next thing I know, I’m traded.”

If the controversies and traits have overshadowed Wilkens’ accomplishments in some circles, they have made little impression on those who work closest to him. “The Seattle people were as far wrong as they could be when they said Lenny wouldn’t fit in with a new coach,” says Cleveland coach Bill Fitch. “Basketball is basically an ego trip; you don’t keep going through 82 games without an ego to drive you. But Lenny is one guy who’s got himself completely under control. There’s no greed or selfishness in him. Anybody can act like a great team man when you’re winning. The real test comes when you’re losing, blowing close games and getting the kind of bad brakes we call ‘Cavalier luck.’ Lenny’s been through that with us—and he’s proved just how great he is.”

In this season’s All-Star game, coach Tommy Heinsohn of the Boston Celtics needed no proof. When Kansas City-Omaha’s brilliant Nate Archibald began destroying Heinsohn’s East squad in the first half, the coach turned quickly to Wilkens. Lenny willingly sacrificed the other aspects of his game to concentrate on stopping Archibald—and his second-half defensive performance was a key to the East’s victory.

Bill Bradley of New York, known for his own cerebral approach to the game, gives a succinct analysis of Wilkens’ basketball brains. “He’s probably the smartest backcourt man we ever face,” says Bradley. “The only guy who might compare to him is Jerry West, but I think Lenny is a little more conscious of mismatches and open men than West. And he has a great ability to deceive the defense. Everybody in the league knows that he’s going to his left almost all the time, but somehow, he makes a little move that convinces you he’s going right—and then he goes to his left again and beats you.”

Many NBA players share Bradley’s opinion—to a far greater degree than outside observers. In his final year with St. Louis, for example, Wilkens averaged only 10 points per game; when the press chose the official All-NBA team, he didn’t even make the second five. But when the players were polled to select a Most Valuable Player, Wilkens placed second to Wilt Chamberlain, who had enjoyed his greatest season. “You get nothing for second,” Lenny says wryly. “But it was still something I could relish—because it was the judgment of the players.”

Perhaps those MVP votes and the recognition he invariably wins when he competes in All-Star games will prove to be the highest honors that Wilkens will ever take from his trade. “I guess,” he says, “the real high point of anyone’s career would be winning a championship—but then I can’t say first-hand.” He smiles resignedly as he speaks, for he knows that an NBA title is now beyond his reach, at least during his active playing days. The Cavaliers are young, eager, and full of potential, but they are years away from serious contention; even an athlete as marvelously conditioned as Wilkens cannot expect to last until their future arrives. “But even if I’m not here to see it when this team finally gets it all together,” he says, “I’ll find some satisfaction in knowing that I helped it along the way.”

Wilkens came to Cleveland reluctantly, holding out until six games into the season while he weighed his home and business interest in Seattle against the lure of continuing his playing career. When he arrived, he might have been expected to be less than enthusiastic about plunging into his new situation. But Wilkens wasted no time in establishing himself in a position that is virtually unique in pro basketball.

As an ex-coach, Lenny is a valuable aide to Fitch, making suggestions, transmitting plans and messages to others during games—and silencing the critics by exhibiting what Fitch calls “the kind of loyalty you can only appreciate when you’ve been a coach yourself.” As a veteran on one of the NBA’s youngest teams, Lenny is the captain, the player representative, and the steadying influence. He is free with advice and instruction to the inexperienced Cavs, and he also offers a vivid example of the kind of hard work and clean living that might keep some of them around the league for 13 years. And as a player, he is still Lenny Wilkens at his best, playing far more than the Cavs had dared to expect and scoring as prolifically as he ever did before.

As leaders of a team, Fitch and Wilkens present some interesting contrasts. Fitch is basketballs, flamboyant master of one-liners, a man who has taken the great gamble of laughing at his own pathetic team—and has apparently gotten away with it. Now that the Cavs are getting less pitiable, the coach is still playing things largely for laughs. “I can’t very well threaten him, ‘Shape up or I’ll ship you to the Lakers.’ We were born crippled in the expansion, and we’re stuck with it. Our farm club has to learn by playing 82 games a year—for us.”

While Fitch entertains and explains at postgame sessions, Wilkens takes defeats much harder, undressing slowly, and keeping to himself in front of his locker. “I’ve never been a good loser,” he admits. “I can handle it, but I’ll never like it.” He understands that Fitch’s manner hides an equally strong will to win—but he will never be able to share in it.

Nevertheless, the two men have enjoyed a rapport from the start. “If some guy sleeping on a park bench has an idea for me, I’ll listen,” says Fitch. “So naturally, I’m delighted to have a proven coach giving suggestions. Look at the job Lenny did in Seattle, holding his team together despite serious injuries. Around here, if the ballboy used to get hurt, we’d go into a slump. As soon as we got Lenny, I knew that my door would always be wide open to him.” The night Wilkens flew into Cleveland, in fact, Fitch picked him up at the airport at 2 a.m., and the two watched films for the next three hours. Two nights later, Lenny was in the lineup—and the Cavs began to look like a different team.

Off the court, Wilkens is not particularly close to the Cavaliers’ young stars, such as Austin Carr, Johnny Johnson, and Dwight Davis. The wide gap in ages naturally steers them toward different social activities, and Lenny’s experience as a player-coach forced him to maintain a certain distance from his players. But the younger men look at him with deep respect and respond enthusiastically to his advice.

He has been especially influential in the development of Carr, the former Notre Dame hero, who is still erratic, but appears a cinch to become a pro superstar. “Austin has more talent than I ever had when I came up,” Lenny says. “But I can help him in using it, by getting him to pick out the easy shots. He’s good enough to take difficult shots and make them, but he’ll be even better when he makes it easier on himself. To do that, he has to keep learning when to penetrate and when to stay outside. He has to recognize situations and take advantage of them.”

In that department, Wilkens is still without peer. “I always had a wide view of the court,” he says. “But maybe coaching expanded my outlook even more. The second I get the ball, I’m watching the whole defense. You’d be surprised how many times forwards will turn their backs on their men as they retreat downcourt; sometimes you can hit an open guy for a basket before the defenders even turn around. Also, you get to know teams’ tendencies: Which ones switch on picks or fade back toward the hoop. That kind of knowledge lets you drive, shoot, or pass without hesitation—and that edge can produce points.”

Executing those plans can be arduous work, of course, particularly when the opposing team happens to be bigger and better than the Cavaliers—as most teams are. So Wilkens takes a fearsome beating in some games without attracting undue attention from the officials. “Any time your game is based on penetrating through the defense,” he explains, “you’re going to get hit. And playing for Cleveland is like playing my first season in Seattle; when you’re an expansion team, if there’s any reasonable doubt on a contact play, you won’t get the foul called. To make it tougher, the top officials don’t usually get assigned to the lower teams. Richie Powers is the best, and we’re lucky if we see him on the court once in a couple of months.”

As painful as the physical aspects of Wilkens’ game may be, he has proven to be one of the most durable athletes in pro ball. Ever since those formative afternoons in Bedford-Stuyvesant, he has been slammed by the elbows and bodies of stronger and taller men, and somehow, he has avoided serious injuries and outlasted them all. The pains that have affected Wilkens more deeply have been inflicted off the courts.

The St. Louis Hawks were a good team, and as the man who quarterbacked their attack, Wilkens enjoyed some soaring moments with them. But he joined them with an $8,000 rookie contract, and they kept him at that rock-bottom level even when he made the All-Star team in his third season—an arrangement he still views with understandable bitterness. “It was,” he says, “the only time I did something really naïve. And I got badly burned for it.”

Later, there was a strange, highly publicized feud that began with a relatively minor matter: In planning a State Department tour in South America, coach Richie Guerin left Wilkens off and took Bill Bridges instead. Somehow the affair escalated to a point where Wilkens and Bridges, both proud and determined men, were each taking offense at almost everything the other said or did. When the Hawks won their division and the season ended with a Lenny Wilkens Night, the squabble was shoved into the background. But it soon cropped up again in the salary negotiations that were to speed Wilkens toward Seattle. The Atlanta group that had bought the Hawks began by making an insultingly low offer to Lenny, then proceeded to dredge up charges that he was selfish, jealous, and a source of discontent on the team.

The nasty accusations were soon forgotten in Seattle, where Wilkens became the star of the team that rapidly won acceptance from the town. Lenny, his wife Marilyn and their three children settled there and began to think of it as home; they liked the city and the team, and management obviously thought highly of Lenny. After one season, owner Sam Schulman offered him the job of player-coach.

“Maybe it was too early in my career,” Wilkens says now. “But I felt it was a chance I couldn’t pass up. Mr. Schulman said it was my team to run the way I wanted, and he kept his word—until near the end. And in my own mind, I had some big ideas about what I could do with my chance to coach.”

Above all, Wilkens was determined to convince his players that they could beat anyone. The Sonics improved steadily, and when Schulman lured Spencer Haywood from the American Basketball Association at the end of Wilkens’ second season as coach, the future looked brighter still. “The guys were getting to be proud of being Sonics,” Lenny recalls, “and the mood projected itself to the fans. It was supposed to be a depressed economy there, but attendance kept going up, and everybody shared in our great hopes.”

The hopes were also the beginning of the player-coach’s problems. As the 1971-72 season approached, Wilkens counted on real progress—as long as several variables turned out for the best. If Haywood shook himself free from litigation and played to his abilities, if Bob Rule came back successfully from an Achilles tendon injury, and if the other key men stayed healthy, Wilkens—and his boss—could reasonably hope for a playoff spot.

None of the good things happened. Haywood was brilliant at times, but he was also distracted by lawyers and critics—and he was injured during the crucial stretch drive. Rule never regained his mobility, and other important men like Don Smith and Dick Snyder were sidelined for important periods of the season. All things considered, the Sonics could have collapsed completely under the strain. Instead, Wilkens’ makeshift lineups compiled the sixth-best record in the league and fell short of the playoffs only in the final days of the season.

“I thought we had reason to be proud,” Lenny says. “But I guess I wasn’t paying attention, because the second-guessing had already reached a peak. I finally read a story that said I couldn’t go on handling both jobs, playing and coaching. It didn’t take much to figure out who planted that story.”

When Schulman verified the story and asked for Lenny’s choice, Wilkens felt little sorrow about ducking the second-guessing and resuming life as a player. By the time new coach Tom Nissalke called and assured him that they would have no problems together, Wilkens was actually feeling relieved. “I felt that I had been part of management, building a team that was going places. And I was happy to keep building it as a player. It was unsettling, to say the least, to find out that they had deceived me all along.” The message came in the form of his trade to Cleveland.

The Sonics began their new season with several million dollars worth of frontcourt talent, all spirited away from the ABA. Unfortunately, they had no one who could make the addition of the “ABA All Stars”—Haywood, Jim McDaniels, and John Brisker—function as a team; they also had no playmaker to help them get open and then get them the ball. The man who might have done both those jobs was occupied elsewhere—helping to make the lowly Cavaliers into a better basketball team than the talent-rich Sonics.

“Yes,” Wilkens says with his soft smile, “it’s a crazy game. But then, these are crazy times.” Beyond that, he refuses to gloat over the Sonics’ misfortunes. As for coaching again, he replies, “It’s something I’d like to do—but I reserve the right to change my mind on that.”

For the moment, playing remains very much in Wilkens’ system. “There are days when I lie in bed, all bruised and tired, and tell myself I really don’t want to play,” he admits. “But when I get to the arena, the adrenaline will start to flow. Then I’ll get dressed, and it will really be pumping. When I step onto the court, I’m really excited by the chance to show my best. Different things motivate different people—and that feeling, that desire to perform well is what motivates me.”

“The guy has played hurt, he’s played sick, he’s play tired,” says Fitch. “If you want to know the meaning of a pro, he’s your best definition.”

Wilkens doesn’t fool anybody anymore: Everybody knows he’s a ballplayer.