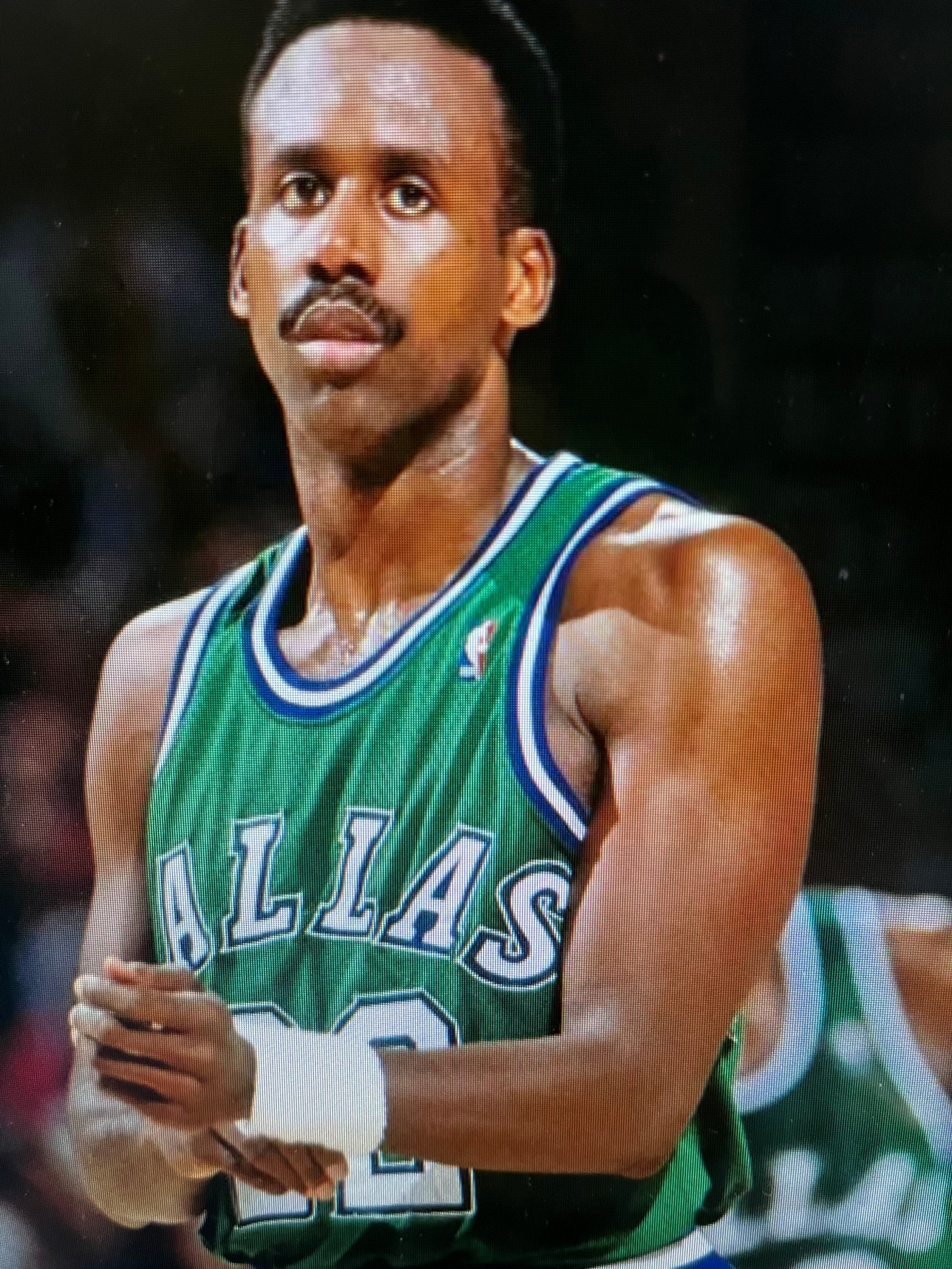

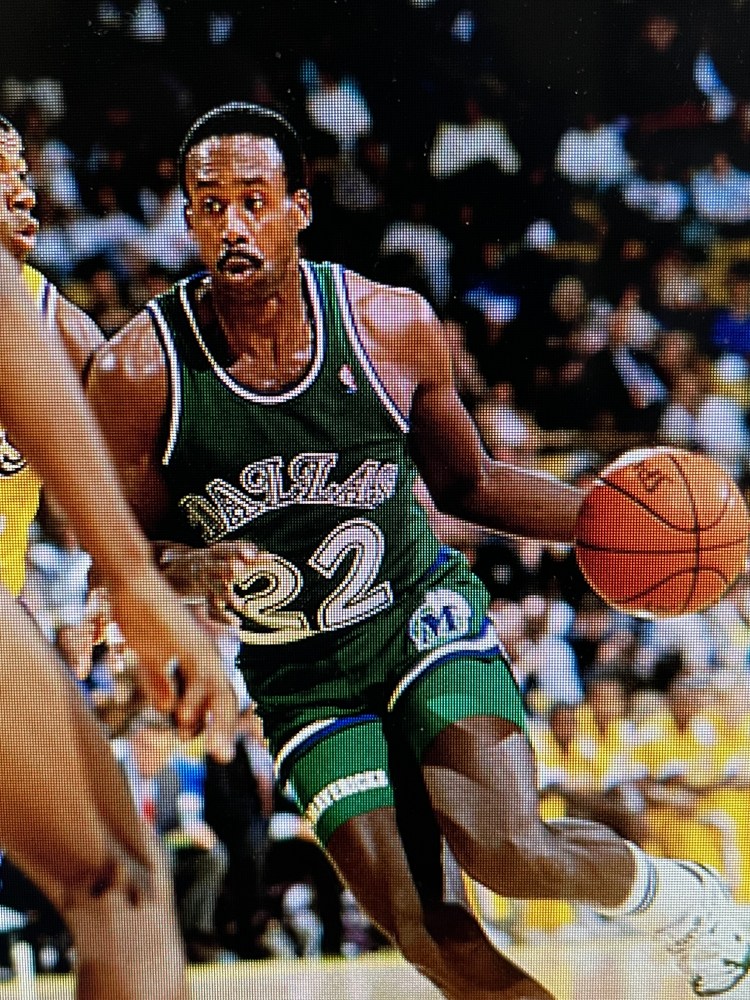

[If Rolando Blackman played today in the NBA, he’d probably spot up behind the three-point line like everybody else. That would be too bad. In the 1980s and well into the next decade, Blackman was a master of rubbing off a screen set by a teammate, reaching for the waiting pass, and knocking down an 18-footer. All seemingly in one long, smooth motion. Blackman wasn’t flashy. He was just deadly accurate and always clutch under pressure. That’s why his NBA memory has aged well among those who watched him early and often over the course of his 13-year NBA career, primarily in Dallas.

But not everyone saw him shine in his era dominated outside the paint by Magic, Larry, Michael, and Kobe. That makes this brief article a good entry point to revisit Blackman’ stellar career. The aticle was published in the 1990-91 edition of Street & Smith’s Pro Basketball magazine. The always outstanding Houstonian Fran Blinebury is at the typewriter.]

****

In a league of sky-walking slam dunkers, his game is very down-to-earth. In an era of individual flamboyance, he always seems to fade into the crowd. If Rolando Blackman were part of the house, it would most likely be the foundation. If he were part of a car, he’d be the quiet-running engine rather than a fancy hood ornament.

For nine years he has toiled with the Dallas Mavericks, and for nine years he has so often been overlooked. Yet as the Mavs have risen from the infancy of expansion to the level of consistent playoff contenders through their first decade in the NBA, Blackman has always been the part of the machine upon whom they could depend.

“He’s not the kind of guy who will do it with words or speeches,” says Dallas center James Donaldson. “But there’s no question that Rolando is our leader. He gives us the same solid effort every night. He plays like an all-star for us, even if most of the rest of the league doesn’t recognize it.”

It’s probably hard for anybody back in his old neighborhood in Brooklyn to recognize Blackman these days. After all, this was once a kid who moved to the U.S. from his native Panama when he was eight years old to live with his grandmother, and he would rather have played soccer than basketball in those early days. But the streets of Brooklyn were filled with boys dreaming of becoming the next Earl Monroe rather than the next Pele, so Blackman began to try his hand at hoops.

Try, that is. Not succeed.

“In those first days of playing basketball, I was awful,” Blackman admits. “I didn’t know how to do anything. I think I was one of the worst players that I’ve ever seen. I couldn’t shoot or dribble or pass or play defense.”

And as you might expect with those few shortcomings in his game, Blackman couldn’t earn a spot on his seventh, eighth, or ninth grade teams at school, either.

But that’s when he first showed the determination and perseverance that have made him one of the NBA’s most-consistent players by sticking with the game and refusing to give up. Blackman also benefitted from a relationship that he developed with Ted Gustus, who coached summer league teams and ran an after-school program at a playground in his neighborhood. Rolando asked for help, and Gustus gave it to him.

“I used to have him in the park at six in the morning to work on his skills and improve his game,” Gustus recalls. “I never cut a player from any of my teams. So, when this kid came and asked me to teach him how to play, I did whatever I could for him.”

What Gustus did was to act as part-coach and part-father figure for Blackman, who eventually sprouted up during his high school years to his current 6-feet-6. It was Gustus who advised Blackman to concentrate on the big guard position rather than become a forward, as so many college scouts were suggesting. He turned down a chance to play at Eastern power Syracuse and nearly 200 other schools and took up residence in a different Manhattan. This one the home of Kansas State, where coach Jack Hartman was willing to put him in the backcourt.

By the end of his sophomore year, the once-shaky Blackman was an All-Big 8 performer and a leader on a K-State team that made it to the NCAA tournament. By his senior year, he had achieved All-American honors, and it was his 20-foot shot at the buzzer that enabled K-State to upset Oregon State in the tournament.

Blackman went on to earn a spot on the 1980 U.S. Olympic team that never got to participate in the Games due to the American boycott of Moscow. That may actually have saved Blackman and the U.S. team from embarrassment, since he was not a U.S. citizen at the time—no one had bothered to check the records—and he may have caused the Americans to be stripped of any medals won.

Nevertheless, just as Blackman had begun to achieve recognition for his own development, he was taken with the ninth overall pick in the 1981 college draft by Dallas in the same year the Mavs made Mark Aguirre the No. 1 choice. Thus, Blackman came to Dallas and took his place in the background as the Mavs made Aguirre the centerpiece of their offense and the franchise’s major star. While Aguirre rode the peaks and valleys of an always-controversial career in Dallas, Blackman was the steadying force on the team. When Aguirre’s disputes often threatened to sink the Mavs, Blackman was there to bail water and keep their ship afloat.

“It was sometimes very difficult to keep your mind on your job with everything that was happening,” says teammate Derek Harper. “But Ro always was the guy who pulled us together and wouldn’t let us be distracted.”

While other guards around the league were becoming household names, Blackman contented himself with being one of the NBA’s most-unheralded performers. Four times he has made the Western Conference All-Star team, but always by virtue of the coaches’ selection, never by the popularity contest vote of the fans.

Blackman’s moment of individual fame came at the 1987 All-Star Game in Seattle when he stood at the foul line in the final seconds of regulation and drilled a pair of free throws that sent the game into overtime. Seattle’s Tom Chambers was named the MVP that day, but it was Blackman’s second-half play and his clutch shots from the foul line that put the West in a position to win the game.

That was classic Blackman, being forgotten again. But he has not been forgotten by Gustus or the people back in his old neighborhood in Brooklyn. He usually returns each summer to spend time with friends and relatives. And he always finds time to stop by the place where he started out. It has now been renamed Rolando Blackman Park.

“He’s a great role model for all of the young kids,” says Gustus. “He doesn’t drink or smoke. He has his head on straight. He stresses education. He has never forgotten his roots and the people and the place that he came from.”

Throughout his career in Dallas, he has never forgotten how to step up and make the big plays when the Mavs have needed them. Blackman won’t make the highlight films with gravity-defying dunks. But he’ll beat his man to the hoop with his stutter-step drive or pull up to stab in a jumper. He plays solid defense, and more than anything else, is just someone who is always there.

“It’s an incredible thrill for me to be in this position,” Blackman says. “Believe me, nobody is more surprised to see me here than I am. I feel like I’m living out a dream.”

Even if his role in the dream is always in the background.