[A few posts back, the blog ran an article from the May 1973 issue of SPORT Magazine about Lenny Wilkens. The article was part of a twofer featuring Providence College grads Wilkens and Mike Riordan. Below is the Riordan side of the story, written by today’s well-known basketball author Charley Rosen. Just guessing, but Rosen seemed pretty cramped for space compared to Pete Axthelm’s more-expansive profile of Wilkens. That’s too bad, assuming I’m correct. Rosen does a nice job with this profile. I just wish he’d had more space, because he clearly was having fun with this profile and Riordan is a great interview. (So is Stan Love.)

One quick musing. Bullets’ GM Bob Ferry told Rosen that Baltimore wanted to run, and that “the quick forward,” like a Riordan, “puts another man out there who can run and get the shot before the defense gets together.” All true, but with a historical sidenote. Bullets’ coach Gene Shue, a former NBA All-Pro in the backcourt, not only wanted to run, but he wanted to get four guys out on the break whenever possible, keeping Wes Unseld home to rebound and outlet. In 1971, when Riordan arrived in Baltimore, four guys out on an NBA break was truly innovative. Most teams could at best muster three at a time.

Shue’s innovation was rooted in desperation. As noted in the story, Bullets’ star Earl Monroe walked out on Baltimore at the start of the 1971-72 season. As also noted, Baltimore was having trouble fulfilling his trade request. Larry Fleisher, Monroe’s agent, had given a short of teams to Bullets’ owner Abe Pollin that his client would play for. Pollin looked it over, then dragged his feet hoping that he and Monroe would reconcile. Their disagreement only got worse, and Pollin belatedly had his GM shop Monroe to those teams on the list. No interest—with one notable exception. New York was willing to make the trade, but it had to be on its terms. Pollin grumbled, and New York’s Ned Irish advised him to take his limited offer while he still could get something in return. (Fleisher was conspicuously shopping Monroe to the ABA Indiana Pacers, mostly for show and to put pressure on Pollin to make the New York trade.)

That something in return was Knicks’ reserve forward Dave Stallworth. Pollin wasn’t pleased. Monroe was an all-star; Stallworth was a New York scrub who also had a bad heart. But Shue, the franchise’s basketball brains, thought Stallworth would fit nicely into his four-man fastbreak that included Archie Clark, Phil Chenier, and Jack Marin. Pollin, hoping to save face, asked for a second play just for appearances. Irish looked down his roster and offered Riordan, who was sidelined with a broken wrist. What’s more, Riordan likely wouldn’t be out of his plaster cast until late in the season.

Pollin reluctantly accepted Stallworth and Riordan, too, while Shue enthusiastically prepared to try out his super-charged fastbreak. A half season, the four-man fastbreak had its moments, but Stallworth wasn’t the dashing forward that Shue had imagined. The irony is Riordan, the throw-in guy, was—and more. And the rest of the story is found in Rosen’s excellent profile of Riordan.]

****

One thousand screaming kids had paid out 1,000 wrappers from Mars candy bars for the privilege of attending a Baltimore Bullets basketball clinic. It was 10 o’clock on a Saturday morning in Silver Spring, Maryland, and while the Bullets sat and suffered, a grandmotherly matron in a red pants suit welcomed the urchins. “But before we meet the”—she glanced at her notes—“the Baltimore Bullets, let me tell all of you boys and girls about something really important.”

Stan Love, the Bullets’ resident flake, opened his eyes wide.

“Mars candy,” said the red pants suit, “has come up with a wonderful new treat. I’m sure you’ll all enjoy. It’s called Munch Peanut Brittle. Tell your mommies and daddies to go to the store and get some.”

Stan Love pretended to gag, violently. “I always get nervous before clinics,” he explained.

The clinic got underway with a question-and-answer session. The first query came from a Cub Scout: “Is it true that Mike Riordan has a map of Ireland tattooed on his belly?”

“No,” said coach Gene Shue, the quizmaster.

“It’s on his face,” came the chorus from the Baltimore bench.

Next question: “What kind of girls does Elvin Hayes like?”

“His wife,” said Gene Shue.

“End of question-and-answer period,” said Elvin Hayes.

Then the Bullets scrimmaged. They were tired after beating the Knicks the night before, and the scrimmage, not surprisingly, was on the loose side. As passes were thrown into the stands, shots were thrown from the hip, and candy wrappers were thrown on the court, Shue muttered an occasional, “Nice defense,” and checked his watch every five minutes. After a decent interval, he nodded to Wes Unseld, and the Bullets sped out the side door and into the dressing room.

Grandma Munch came running over to Shue. “But the clinic, the clinic,” she pleaded.

“You just saw it,” said Shue.

After a cold shower, no soap and a shortage of towels, Riordan and Rich Rinaldi drove north together to Baltimore. The $25 that each had earned did nothing to brighten their mood. “It’s the big time,” said Rinaldi. “Peanut brittle and the NBA—what a parlay!”

Riordan, too, was angry, but for a different reason. “Damn it,” he said. “We’ve got a tough game against the Lakers tomorrow. We should all go to another gym and have a real practice for a couple of hours.”

****

“Mike Riordan definitely has three lungs—he’d make a great marathon runner,” says Baltimore general manager Bob Ferry. “Did you know that he’s second in the NBA in minutes played? He’s just perfect for us—he fits into our type of game like the last piece in a jigsaw puzzle.

“The defense up here is just brutal,” he continued. “Every team plays some kind of sophisticated zone, and they all have the big man back there blocking up the middle. Once they get a chance to set up, it’s hard to get your offense moving freely.

“The way we see it is that a team must break in order to win. The quick forward puts another man out there who can run and get the shot before the defense gets together. The whole league is going this way; look at guys like John Havlicek, Lou Hudson, and Bill Bradley. We have Wes Unseld and Elvin Hayes to handle the boards, so Mike can be on the break as soon as the shot goes up. The Knicks never had the board strength for Mike to play this kind of game.”

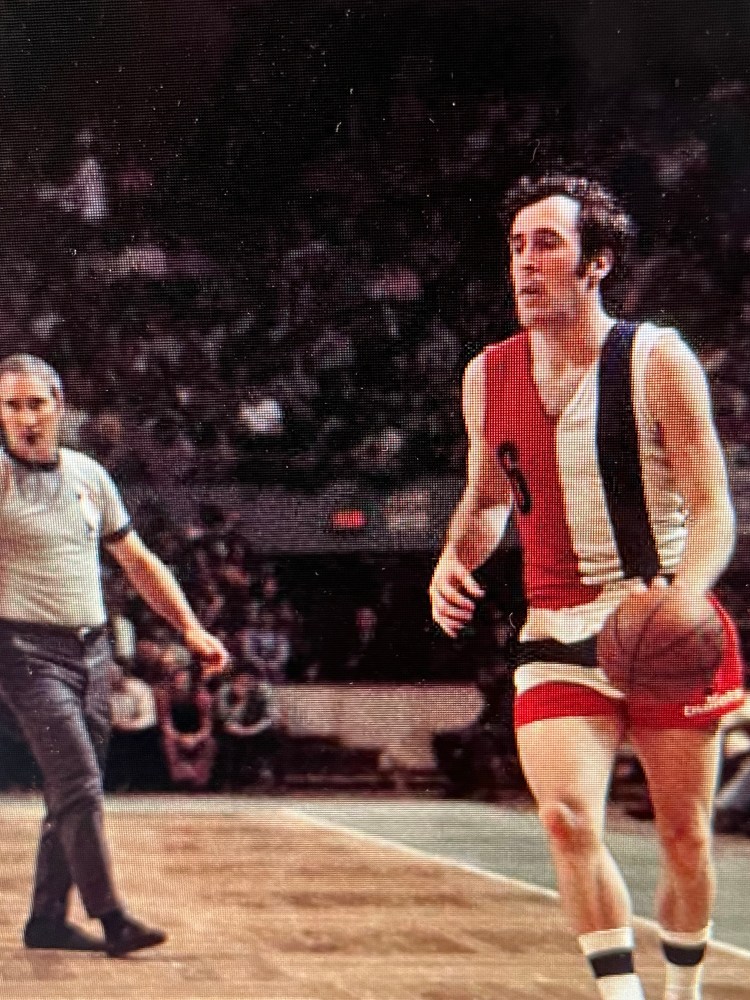

Mike had been the first Bullet out on the Civic Center floor for the Knick game. After trading jump shots and gossip with two New York early birds, Phil Jackson and Jerry Lucas, Riordan launched into a dozen full-court wind sprints, dribbling hard from one basket to the other. He didn’t stop running until the game was over.

The Bullets won, 89-77. Mike’s line in the scorebook wasn’t impressive—46 minutes played, eight points, eight rebounds, and two assists—but he had done things which couldn’t be graphed, added, or averaged. For example, Archie Clark, just recently signed after a 43-game hold-out, had his troubles chasing Walt Frazier in the first quarter. Clark looked like a candidate for a whirlpool bath; he had scored nothing, and the Bullets trailed, 22-15. In the second quarter, Riordan played guard, shut out Frazier, and got the Bullets’ offense moving again.

At forward, Riordan guarded Bill Bradley; Bradley got only eight shots and six points. “Mike is quick and smart,” Bradley said after the game. “It’s hard to shake him on a pick or screen; he beats me to the spot or he fights his way through.”

****

Mike Riordan comes from Bayside in Queens, the fringe of New York City, and he leans toward the Bayside mod look. Soiled sneakers, stained dungarees, and spotted sweatshirts. He also wears an off-white undershirt, torn around the neck. “So that the hair on my chest shows when I wear open-neck shirts,” Mike explains.

The leprechauns who watch over Mike have compensated for his lack of sartorial flare by imbuing him with an honest, friendly manner, and an open face. Everything about Riordan makes people feel comfortable.

He is a family man, devoted to his wife and his two daughters. He is a dedicated athlete, totally committed to basketball as a way of life. He is sincere and guileless, without a trace of pretense. It sounds almost corny, but Mike Riordan is a good man to visit, a good man to know, a good man to team with on the court.

Mike Riordan started playing basketball when he was five years old. He went to Holy Cross High School in Bayside and played in the shadow of Kenny McIntyre, who went on to become a star at St. John’s and a washout in the NBA. “Kenny scored 25, 30 points a game,” Mike recalls, “but somehow, I managed to get named to a couple of honorable mention ‘all’ teams—it was no big deal—and I got a handful of scholarship offers. But my coach knew a guy who knew a guy who played college ball with a guy who was a ‘gopher’ for Joe Mullaney at Providence.”

Mike wound up at Providence in the post-Lenny Wilkens era. It was the Jimmy Walker era. “Jimmy was unselfish,” says Mike, “but he averaged over 30 a game, and that didn’t leave a whole lot left over for the rest of us. I got about 14 my senior year, but most of it was on garbage and on just following Jimmy around and putting in what dropped off him.”

Pro scouts flocked to Providence to check out Walker, and at least one of them also liked what he saw of Riordan—Red Holzman, then the Knicks’ chief scout. “Mike was a hard worker, played good defense, ran all night, needed work on shooting and ballhandling,” Holzman remembers. All of Mike’s hard work at Providence got the Knicks to select him only as a “supplemental” pick in the 1967 NBA draft.

Riordan might have disappeared without a real test if it hadn’t been for Bill Bradley. Scholar Bill had just emerged from Oxford, and in June of 1967, the Knicks were eager to see what he could do. Mike just happened to be in the neighborhood, and the Knicks invited him and a few other warm bodies to come down and work out with Bradley. A floor was thrown down at the Garden and, for four days, the Knicks studied Bradley. They had no choice but to take a look at Riordan, too. Mike was in good shape, as always. The Knicks told him to come back to camp in the fall.

“I played in the regular training camp,” Mike says, “but there was still no room in the Knicks’ backcourt. They suggested that I play with Allentown in the Eastern League. I was kind of taxi-squadded.”

Holzman, now the Knick coach, insists that New York paid Riordan nothing while he was with Allentown. Mike says otherwise. “They paid me half of the minimum, but I never signed a contract with the Knicks. I guess they try to keep that stuff quiet; it’s probably illegal. If I had signed and they wanted to cut me from the big club, they would have been forced to put me on waivers.”

The Eastern League is a basketball limbo for rookies who lack the speed, the shot, or the savvy to play pro ball—and for aging players hanging on for another paycheck. From this graveyard, Riordan rose to the NBA the following year.

The cynical know that the NBA expanded in 1968 for the sole purpose of enriching the league’s owners. The more enlightened realize that expansion was merely a plot to deplete the Knick backcourt and get Mike Riordan into the league.

For the next year, during the 1968–69 season, Mike’s uniform stayed clean and dry; mostly, he just mastered the art of giving fouls, an art now extinct, killed by a rule change. “It had to be done,” he says, “and I didn’t mind doing it. It was just a way of getting time that I wouldn’t have gotten otherwise.”

Putting occasional bearhugs on opponents is not the way most ballplayers improve their game, so whenever the Knicks were off, Mike would turn up at St. John’s or Hofstra or any place he could get a workout. Mike polished his shooting during these pick-up games and, not being an exceptional one-on-one player, learned to use his teammates’ picks and screens to get his shot off.

Mike worked hard and learned well and, in his second year with the Knicks—their championship year—he became the third guard behind Walt Frazier and Dick Barnett. “My role on the club,” Mike says, “was to play defense, take the ballhandling pressure off the other guard, and get the ball to the shooters.” Occasionally, Mike would get to play most of the game —usually when somebody was injured—and every now and then, he’s exploded for 15 or 18 points. Many of his explosions seemed to come against Baltimore. So, it wasn’t a major shock—just a minor one—when the Knicks traded Riordan and Dave Stallworth for the Bullets’ Earl Monroe in the middle of the 1971-72 season.

“Monroe didn’t want to play here anymore,” Gene Shue says, “so the trade was a forced one. There just wasn’t a whole lot available because many coaches were afraid of Earl’s style. Let’s face it, at the time, Mike was just sitting on the bench. Stallworth was the established player; he was the guy we thought would be playing for us.”

When Mike arrived in Baltimore, he had a bad wrist and a good seat—right on the Bullets’ bench. But the wrist soon healed and, when starting guard Phil Chenier injured his leg, Riordan got to start the last 16 games of the 1971-72 season. Shue told Mike to flatten out his jump shot, and suddenly Riordan began to score. He finished the year averaging 9.5 a game, nearly twice as much as he had scored as a part-time Knick.

The Bullets played well the day after the peanut-brittle clinic, but everything Los Angeles threw up went in. The Lakers won a close ballgame. Riordan played a fairly typical game. He scampered around with that long-armed, chesty run of his, contributing 14 points, six assists, and a good defensive job on Jim McMillian, whose new fur coat had been the subject of much pregame chatter. Stan Love of the Bullets summed up the coat in three words: “It’s just bait.”

As McMillian groomed his fur after the game, he talked about what a chore it was to go against Riordan. “Bags [a nickname Riordan acquired in New York] runs so much,” said McMillian, “that you have to concentrate 100 percent on defending him. This means that you have to rest on offense, which, in turn, makes it easier for him to play you.”

In the Bullets’ locker room, Gene Shue talked about Riordan with almost patriotic zeal. “I like everything about him,” Shue said. “It’s been an uphill struggle for him all the way, but he has seized every opportunity and made his own breaks. I admire people who go out there every day and do their jobs without bellyaching about everything. Hard work and dedication—that’s the American way.”

****

Stan Love was sitting at a rock concert, listening to a group called Traffic, lost in a young, nubile crowd. “Nah,” said Love, “Bags never goes to these things. He is as straight as an arrow, but you’ve got to love him. There are a hundred guys in the league with more physical ability than he has, but nobody drives himself any harder.”

Love paused to eye a few passing bodies. “The dude just never stands still. Sometimes I have to guard him in practice. When I lose him, I just hang out and pick him up the next time he comes around.”

Love shook his head. “I mean,” he said, summing up Riordan as neatly as he had McMillian’s fur, “you can break a sweat just watching him.”