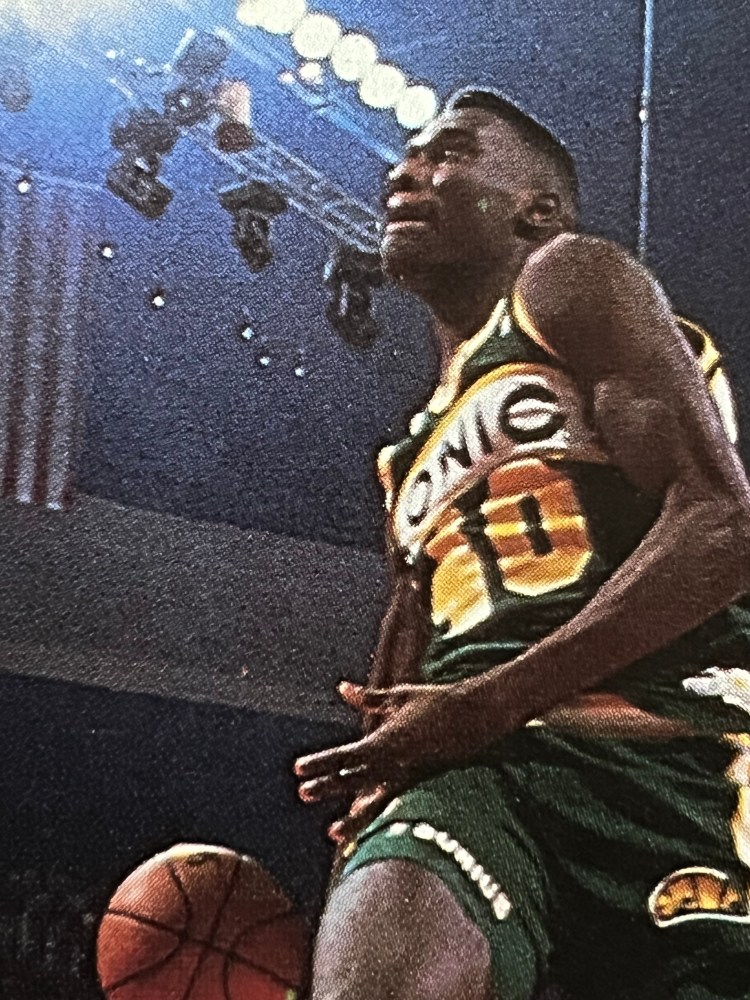

[By late 1991, the NBA was smitten with Seattle’s essentially prep-to-pro prospect Shawn Kemp. “He’s a star already,“ beamed Seattle coach K.C. Jones. “You can’t go anywhere without hearing ‘Shawn Kemp, Shawn Kemp, Shawn Kemp.’ That’s the fans, that’s the media, that’s everything else.”

But several months earlier heading into the 1990-91 season, Jones was more circumspect. In his eyes, the sky was certainly the limit for the 6-feet-10 Kemp and his wowing strength and athleticism. But “the kid” still had a lot to learn. What follows is an article, featured in a 1991 issue of Hoop Magazine, about Kemp starting his sophomore NBA season. The story, written by the magazine’s Indiana-based contributor Carl Grody, records Kemp’s early musings and those of others about his future. Definitely worth the read.]

****

Shawn Kemp is not an average 21-year-old.

He stands 6-feet-10. He weighs 240 pounds. And he entered the NBA last season, while still a teenager and without any college playing experience to boot.

Kemp, who turned 21 on November 26 (meaning he wasn’t even old enough to buy beer when the season started), is in his second year with the Seattle SuperSonics as a power forward—an NBA position most college-aged players would find, at least, intimidating.

What’s more, Kemp moved into Seattle’s starting lineup earlier this season after the Sonics traded high-scoring Xavier McDaniel to Phoenix. Kemp’s play since becoming a starter has been impressive, especially for someone so young.

Intimidating? If anything, it’s Kemp’s rivals who are in awe.

“I think it depends on who you’re talking about,” said Bernie Bickerstaff, Kemp’s head coach with Seattle last year and now the general manager of the Denver Nuggets. “I don’t think Shawn Kemp was the average 19-year-old when he came into the league. I think he handled 82 games better than some veterans.”

Kemp didn’t wilt under the pressure of playing in the NBA. In fact, he regrets not joining the league sooner than he did. “I pretty much knew I could play in the NBA,” Kemp said. “I never get intimidated by my opponent. I’ve been playing with NBA players (in pick-up games) since I was a freshman in high school.”

So,it was a natural progression for Kemp to become the first teenager to play in the NBA since Darryl Dawkins and Bill Willoughby came into the league in 1975. Dawkins, the draft’s fifth pick overall, was selected by the Philadelphia 76ers; Willoughby went to the Atlanta Hawks as the 19th pick overall. Dawkins lasted 14 seasons in the NBA, Willoughby eight.

“The only thing that kept us from pursuing a move directly into the NBA out of high school was that so few other players had ever done that,” said Jim Hahn, Kemp’s high school coach.

Staying off the court for a year after high school while attending Trinity (TX) Valley Junior College, Kemp decided to take a shot at the NBA. He declared himself eligible for the 1989 NBA Draft, and Seattle—which had both the 17th and 18th picks in the first round—jumped at the chance to nab him with its first choice.

“We had no reservations about it,” Bickerstaff said. “He has unlimited talent. We weren’t reluctant at all.”

Hahn knew from the beginning that Kemp was going to be something special. “He was a great player,” Hahn said with a chuckle. “We felt all along that he really has a great shot at being an NBA player.”

As a 15-year-old high school freshman, Kemp was thin, 6-feet-8, and had sore knees caused by growing too quickly. But Hahn still had Kemp playing for the varsity team at Concord High School in Elkhart, Indiana, which is located near the Michigan border. The team had finished 5-16 the year before while waiting for Kemp and his undefeated eighth-grade teammates to graduate, and Hahn knew Kemp was just the player to pump new life into the school’s ailing program.

In four seasons with Kemp in the pivot, Concord was 85-19, a winning percentage of .817. During Kemp’s freshman season, Concord won the sectional title, and the next year Concord won its first regional title ever. During Kemp’s senior year, Concord finished 28-1; its only loss was in the state championship game.

Kemp’s ability attracted attention from across the country, and he became an easy target for ridicule and rumor. “People don’t have any idea what they’re talking about,” Hahn said. “All through high school, people were saying he couldn’t read and write. That’s ridiculous. The stories just grow and grow. It’s like when you start a sentence at the end of the room; by the time it reaches the other end of the room, it’s completely different.

“All along, when he was going through here, he was a good kid. He did all the things we asked him to do. All the little kids around here just loved him. He’d come out every game and talk to the kids and sign their programs. He never put himself above anyone else. He did the same drills and the same work as everybody else.

“Some of the stories I heard about Shawn . . . I think a lot of it was unfair. He was very much under a microscope. He was a big target for a lot of people. But I was happy with the way he handled his career here.”

So, apparently, were many college recruiters and even a couple of NBA teams. “There were (NBA) teams interested in me straight out of high school,” said Kemp, who declined to say which teams. “But I told them I wanted to try college first.”

Kemp enrolled at the University of Kentucky, where many rated him as the best basketball prospect to attend the school. But he was declared ineligible for his freshman year under Proposition 48, then came his alleged involvement in the pawning of stolen jewelry, an incident for which charges never were filed. Kemp decided to leave Kentucky for Trinity Valley JC, where coach Leon Spencer spoke highly of him, even though Kemp never got to play a game there.

“He’s the best player to ever come through this conference,” said Spencer. “Shawn is a good kid who grew up without real direction. But he’s got some direction now because of basketball. It really was an honor to be around a player with that much talent.”

“I think he learned a lot that year by sitting out,” said Hahn. “He told me it was a great learning experience.”

Kemp jumped at his next chance at the NBA. He called friends who were already in the league to see what they thought about his decision to enter the draft without any college experience on the court.

“It helped me out a lot because I could sit down and call them and ask what they thought,” he said. “I didn’t have any of them tell me to wait. Some of them told me to go back to school during the offseason. The opportunity was there (to join the NBA). I needed a change in my life, and that was it.”

Unfortunately, as Kemp was maturing as a person, his game was growing stagnant. When the school year was over, he headed for Los Angeles to play in pick-up games with NBA players at UCLA for three months, hoping to impress the scouts who attended the games.

He did. The result was a six-year contract with Seattle and a chance to play on the front line that included Xavier McDaniel, Michael Cage, Derrick McKey, and Olden Polynice. That stock of veterans made it possible for the SuperSonics to bring Kemp along slowly while he learned the nuances of the pro game.

“I would tend to think it would be very difficult (for him),” said current Seattle coach K.C. Jones, who was an assistant with the Sonics last year. “He really didn’t have any college orientation to the pros. He struggled offensively. There is a disadvantage in coming in so young in the NBA.”

Jones has seen several players—Dawkins, Moses Malone, Willoughby—turn pro straight out of high school. And he saw a common problem for each of them. “They just totally relied on the natural talents they had,” Jones said. “The maturity was not there. With Shawn, this is an important time. You have to augment the talent you have by working hard.”

But Kemp doesn’t like being compared to the others who bypassed college to play pro ball. “A lot of times that hurt me because the public focused on Darryl (Dawkins) because he did a lot of talking,” Kemp said. “I’m a quiet person. And my game is a lot different than theirs.”

Kemp admitted it’s tough to move straight into the NBA without college coaching. “It’s a disadvantage because you learn so much (from college),” he said. “I spend a lot of time (with coaches) in the summer catching up. But I don’t look at myself as a project at all. Teams only say that until you get (to training camp) and earn your playing time.”

“I think the year’s experience has given him a sense of being a pro now,” Jones said. “He’s gotten a lot of attention across the NBA for his shot-blocking and dunking.”

That showed midway through his first season, when he participated in the Gatorade Slam-Dunk Championship at the All-Star Weekend. He led the competition after the first two rounds and eventually finished fourth.

And, considering his age and experience, Kemp got decent playing time during his rookie season. He averaged only 13.8 minutes per game, but he played in 81 of Seattle’s 82 games. He averaged 6.5 points, 4.3 rebounds, 0.58 steals, and 0.86 blocks per game; not Hall of Fame numbers, but good statistics relative to his minutes played. If, for example, Kemp had averaged 35 minutes a game with the same productivity, he would have averaged 16.5 points, 10.9 rebounds, 1.47 steals, and 2.18 blocks per game.

“I thought he got some good time as a rookie,” Hahn said. “I really think that as time goes on, he’ll become a starter. I think he has a very good attitude about being in the NBA. I think he has higher expectations of himself than other people do.”

“Bernie didn’t like to play a lot of rookies,” Kemp said. “You have to earn your playing time. I earned all the playing time I got. At first, they were overprotective. But out of 82 games, I played in 81. I can’t complain about that.”

He’s working for more playing time this year. He spent the offseason trying to improve the range of his jump shot, working on being more of an offensive threat. “That year off that I didn’t play really hurt my jump shot,” Kemp said. “But I’m always comfortable shooting the ball. If I get the opportunity to shoot, I’ll shoot. But you need a quicker release in the NBA. In high school, when you’re taller than everyone else, you don’t have to worry about your shot being blocked.”

“To really be dangerous, you’ve got to get something that works for you on the offensive end,” Jones said. “He has to work on his moves down low. He’s a great passer. He handles the ball very well. He rebounds very well. He’s also a good shot-blocker. It’s out there. He just has to develop it.”

Kemp is also trying to develop himself off the court. He went back to school last summer, attending Indiana University-South Bend. “I’m not disappointed with anything that happened in my college career,” Kemp sad. “If I did anything different, I’d hit the studying part harder in high school so I could pass my SATs.”

But for the moment, Kemp is concentrating on helping the SuperSonics. “This team, they’re depending on me to come in every night and play well,” Kemp said. “When you’re a rookie, they really don’t know which player is going to show up each game.”

Jones, saying that Kemp’s playing time this year “depends on how he comes along,” expects good things to happen in Kemp’s career. “He can go up for a rebound four or five times without stopping,” said Jones. “That says a great deal right there. It depends on the mental approach. He’s a very sharp youngster. He just needs to keep working at it.”

Or, put simply by Kemp, “You just have to be prepared to play the game.”

“His biggest weakness is just being young,” Bickerstaff said. “It’s unlimited (how good he can be) if he just keeps his demeanor and doesn’t let the game go to his head.”

“He’s gonna take it right at you,” Hahn said. “That’s the way he’s always been, no matter who it is. During training camp as a rookie, he said, ‘I had to go right at ‘em. If I was gonna take the elbows and just lay back, I would’ve been in for a long year.’”

As it is, Kemp figures to have a long NBA career instead.