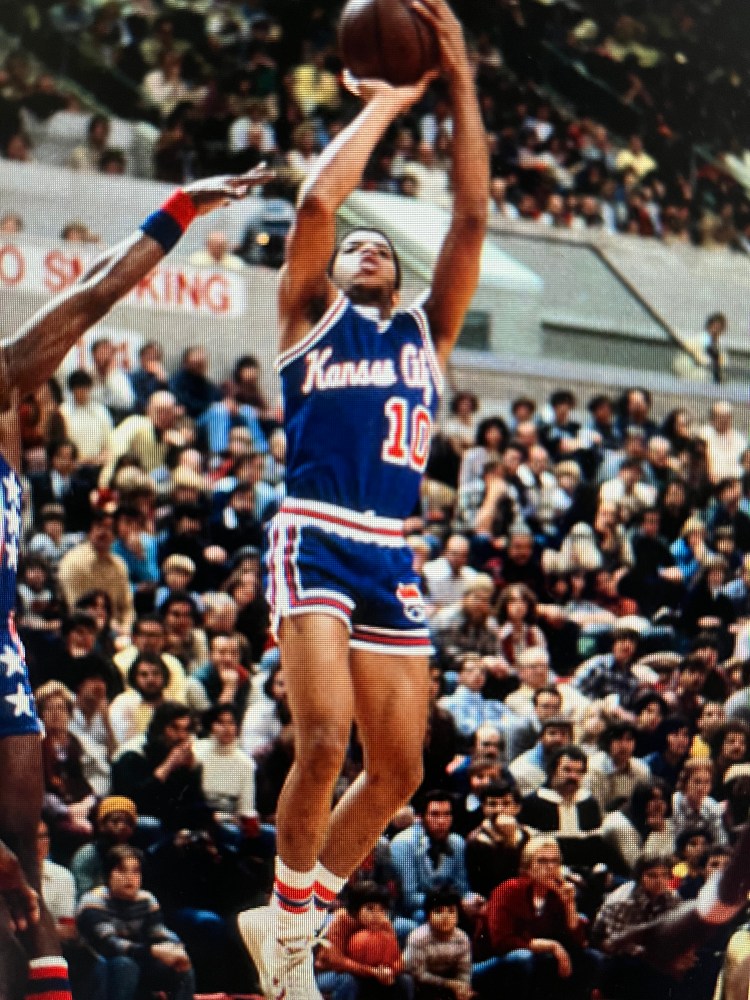

[Everybody has their favorite NBA names. One of mine is Otis Birdsong, the outstanding shooting guard who dribbled out 12 mostly stellar NBA seasons (1977-1989). What follows is a story from the May 1978 issue of Basketball Digest that introduces Birdsong, the number two pick in the 1977 NBA draft and now a member of the hard-pressed Kansas City Kings. What scouts loved about Birdsong was his seemingly unlimited shooting range, high shooting percentage, great court sense, and willingness to move without the ball.

This article, from writer Derrick Jackson, delivers in capturing Birdsong, the personable NBA rookie. But it doesn’t really parse his skills on the court as an up-and-coming NBA star. So, consider Jackson’s piece to be an introduction to Birdsong the person, with more to come on the blog later about Birdsong the player and keeper of one of most-melodious NBA names of all-time.]

****

A couple of hours after the Kansas City Kings lost to Portland, Otis Birdsong slurped the last scoop of his ice cream, making the sound of a young man going on old age. “What can you do? If we could win only one game, then we could go home and get started again. I can’t wait to get back to my own city, my own bed, my own telephone. This hotel, I can’t believe it. The bed’s at one end and the telephone’s at the other end of the room.”

His last purchase of the night was a bottle of beer. Birdsong, before opening the cap, twirled the bottle. It was a classic scene—he was in thought, eyes focused on the bottle. The twirling was symbolic.

“Y’know, my mother had these things she didn’t want us to do. Like please don’t smoke or snort dope—that stuff was easy to get where I’m from. Please don’t get drunk. Y’know, stuff most people go through. She doesn’t mind a beer now and then. When she knows we’re coming to town, she goes out and buys a bunch of beer so she knows we won’t get into anything else.

“When I was a senior in high school—not back in junior high, mind you—I still got a beating. It wasn’t from my mother, though. There was this week where me and some of my friends were going out, driving around and doing nothing until two and three in the morning. She told me to get home by 10 or 11.

“But you know how it is with friends when they just drive around in cars. Finally, my mother got tired of waiting and worrying. She told my older brother. He took me in the back and gave me 100 licks. I was really angry. But then he said, ‘Do you want to fight about it ?’ After that, I didn’t stay out late.”

In this day and age of sports, there are some aspects of the 22-year-old life of Otis Birdsong that would send the straightest people into shock therapy. In basketball, the most-notable event happened last year at the University of Houston when he sent letters to opposing coaches and to some members of the media for stories. [Editor’s note: Not sure what’s meant here. I’m assuming Birdsong sent letters in advance offering to make himself available for interviews and stories while in town.]

Who ever heard of that? You’re supposed to seek the opposition, wipe them out—which he usually did—and leave the burial to the immediate family. “Art Casper, the radio announcer at school, suggested to me that it might be a good idea,” Birdsong said. “It sounded kind of nice. He brought me the envelopes, and I sent them out.”

Birdsong jokes around and exchanges blue language at practices just like any other player. But when he is talking quietly about his life, the word “Christian” is a frequent visitor to the conversation. “If you live a Christian life,” he said. Or, “When I meet the special someone, she’ll have to be a Christian.”

When it was suggested that there are other religions, he said, “They’re all basically the same thing. Me, I believe that if you believe in Jesus Christ, that will set you free.

“I guess it comes through the family. My father was a minister. He died when I was nine years old. I don’t remember that much about him. My mother kept the family up. Still, I remember this one time in church when my daddy is giving the sermon, me and one of my brothers were picking fun at the deacons. Man, we got a whopping when we got home.”

****

Birdsong’s life now is at this point: You could walk all over Winter Haven, Florida, his original home; drive the massive freeways of Houston, the area of his college playing days; or converse with anybody in Kansas City, and the chances of finding somebody talking bad about him are about as good as hearing his present coach Larry Staverman call referees nice guys.

“If Otis wanted, he could take as many shots as Walter Davis or Marques Johnson (referring to the other top rookies in the NBA) . . . He passes up taking around 10 shots a game to get it to somebody else,” said former Kings coach Phil Johnson. “I first met him when they flew him in (on draft day). He struck me as a quiet individual, one who it takes time to get to know. We’ve been lucky. Look at our draft choices recently—Otis, Richard Washington, Scott Wedman. All good people. That’s important on a basketball team.”

Birdsong is quiet while in the public eye, but by the first preseason game, he’d meshed with the other players. On the first day of training camp, when he saw that the Kings were giving him Adidas shoes, he joked to a couple of players, “I’ve got to have my Converse. Converse are the only way to go.”

In his book Life on the Run, Bill Bradley wrote that the Knicks got along because there was a certain accepted set of players that gave quotes to the press, another set that was the acknowledged jokers, and others who willingly remained in the background, letting their performances speak for them.

On the Kings, Birdsong has a little of all those elements. Wedman is the quietest player among the regulars. Birdsong is always modest when the pens and recorders are rolling. When the Kings won the first road game in Cleveland, he received a lot of attention for his scoring, so much that he missed a postgame radio interview. “What did I do to deserve 15 reporters hanging over me?” he asked.

While Sam Lacey, Bill Robinzine, and Washington are the main comedians, Birdsong’s growing confidence in his play is being accompanied by his more relaxed attitude. At the end of a recent practice, he and Washington challenged each other to a quick one-on-one duel, with Birdsong doing all of the offense.

Birdsong drove to the right, went up with his familiar hesitation move, and the ball rolled off his fingertips, just over the outstretched hands of Washington and into the basket. Birdsong drove again. Again, it was to the right. Same hesitation, same finger roll. Washington watched the ball go in. Birdsong strutted back to the top of the key, his hands flicking out in a gesture of cool and his head bobbing up and down.

Washington was humorously irritated. “Forget you, rookie,” he said. “You can’t do it again.” Birdsong burned him once more, and now his gestures were exaggerated. His strut was in full pomp, and his hands were receiving five from everybody in the vicinity. At that moment, he was THE man.

“Can’t stop the kid?” he said to Washington. Once again, Washington said, “Forget you, rookie.”

****

There is an irony to the effortless moves, the breaths he draws out of the fans of opposing teams when he stops and sends in his breakaway jumper, as everyone else is catching up with his last dribble.

Though his are the actions of a young man who was the top guard and second player chosen in the National Basketball Association draft last June, Birdsong didn’t have the recruiting world on his shoulders until he was a senior in high school.

“When did Martin Luther King get shot?” asked Birdsong. “Nineteen sixty-eight? Well, anyway, when I was in the 10th grade, integration had put us into Winter Haven High, the first time Blacks had ever gone to that school. There were riots and stuff the first day. There was always some commotion. There wasn’t much unity of any kind.

“The next year, we all came back to school and absolutely nothing happened. Our white players and the black players got so close we started going out together to the Pizza Hut after games. The funny thing was, as a sophomore, the varsity was so good that I didn’t even play. We lost the championship game of the state to West Palm Beach—you’re not going to believe this—in seven overtimes. Seven.”

As a junior, he averaged 16 points a game, improving to 33 by his senior year. His team lost in the title game again, finishing with another 23-2 record. Because he was impressed with the words, actions, and reputations of coaches Fred Schaus, Gale Catlett, and Guy Lewis, he narrowed his college choices to Purdue, Cincinnati, and Houston. He said he chose Houston because it was far enough away from home, yet not too far. Besides, it was warm there.

The Houston team had promise. By Birdsong’s senior year, it advanced to the championship game of the National Invitational Tournament, losing to St. Bonaventure. But his freshman beginning was rocky, being set off by, of all things, a victory.

“We had beaten Virginia Tech in the Sugar Bowl Tournament, but for some reason, when we got back in the locker room, some of the players started bitching about who didn’t pass to whom, who wasn’t getting their shot. I was getting homesick, and I guess I didn’t feel like I was getting enough playing time. Everybody on the team was going his own separate way, and I felt bad enough that I wanted to leave.

“Later, after the Sugar Bowl, we were going to play in our own Bluebonnet Classic. We had two days of practice before it, but I flew home to Florida to think about it. People convinced me to keep on trying, but I missed my plane the next day on purpose to make totally sure.”

When Birdsong got back to Houston, there still was divisiveness, but it was soon soothed by a let-it-all-out team meeting. “When my turn came to speak, I just said that we should cut it out,” said Birdsong.

Birdsong didn’t walk around campus like a robot either, just pleasing the crowd and retiring to a boring existence. He had fun, but he paid for some of it. As a freshman, he shot off firecrackers, getting booted out of a dorm.

Early in his junior year, he was in on pranks that led to an important moment. He had taken a record album sleeve, filled it with shaving cream, slipped the open end underneath a dorm door, then stomped on the sleeve, sending the lather all over the dorm room. There also was an infamous water fight, which left rooms and a hallway soaked.

“Coach heard about it and called me into his office,” said Birdsong. “I knew he knew, so I tried to play it off by jumping up real fast, saying, ‘You know I did it? What’d you call me up here for? Hell, you know I did it!’

“When I got back to my room, I realized something. I had just about cussed the man out. I felt like crying. I went back the same day and apologized. Now it’s like he’s my dad.”

If nothing else, Lewis became Birdsong’s best publicity agent. On a national telecast against UCLA last season, every other word that Lewis spoke started with “bird” and ended with “song.” Lewis once coached Elvin Hayes, but that didn’t stop him. Birdsong was the best, Lewis said.

Phil Johnson had simple words for his first encounter with Birdsong. “I was watching a game of college stars against the Yugoslavian team, and I had really gone to see people like Tree Rollins and Robert Parish,” Johnson said. “I really had not received a lot of attention about Birdsong (then a junior and likely to remain in school another year).

“When I left the game, I was thinking that Birdsong was one of the top two guards in the country.”

The praise did not stop the hurt that Birdsong felt later. He played in several all-star games, including the Pan-American Games, only to be cut from the Olympic roster. He was one of the last three to miss the squad of 12. “What can you say?” Birdsong said. “Coach (Dean) Smith is such a great coach, and he did bring home the gold. I guess I just wasn’t what he was looking for.

“It hurt my family a lot. They were all going to fly to Canada to watch me play. It was one of those few times, where my mother slipped from being so strong. When I told her on the phone I wasn’t going to Montreal, I could hear her about ready to cry.”

When Birdsong talks of the disappointment of not having his family watch him, there was an extra meaning. Birdsong is one of 12 children, who, with the exception of a mentally challenged sister, are all doing something constructive with their lives. The occupations read: head dietitian at a Washington hospital; executive at a soft-drink firm; electronic technician; bank teller; former running back at Hawaii, who hopes to sign as a free agent with the Miami Dolphins; telephone company workers (three sisters); college student.

Birdsong found strength in his failure to make the Olympic team. In his senior year at Houston, he averaged 30 points a game, hitting 57 percent of his shots.

Shortly after, he put on a Kings’ uniform and began to draw the praise of anybody who was asked. From George McGinnis to Coach Bill Fitch of the Cleveland Cavaliers to Norm Van Lier, the phrase “will be great” became a Birdsong label.

Almost half a season is gone, and the interesting thing is that Birdsong, while suffering with the team through its losing ways, already has achieved the playing confidence that makes him a potential force for changing the Kings’ ways. He’s not a nervous bystander.