[By 1971, Mike Z. Lewin had relocated from his native Indianapolis to New York, with plans to move to Somerset, England. He wanted to study chemistry at Cambridge University. But the 26-year-old Lewin, who’d taken up writing on the side while attending Harvard, would soon publish his first detective novel titled, Ask the Right. The 1972 novel would be the start of his long-lived detective series featuring Albert Samson, a fictional Indianapolis-based private eye. Samson, a low-key, Columbo-like sleuth, stumbles into crazy cases and bumbles his way forward to crack them. For lovers of detective novels, the Samson series and Lewin’s later gumshoe creations are highly prized and highly anticipated.

But before Lewin departed for England, where he’s now lived for decades in the city of Bath, SPORT Magazine asked him to write a feature story on the high-scoring Indiana Pacer, Roger Brown. “One of my better assignments,” Lewin later quipped. What follows is the result of that better assignment, published in the magazine’s February 1971 issue. Lewin’s 3,000-word profile features no private eyes or puzzling clues, just Brown bouncing back from knee surgery and struggling through a rare off-night shooting.]

****

It’s a night practice in Indianapolis in early November. Bob Leonard, coach of the Indiana Pacers, is screaming at his American Basketball Association champions. He is trying to get them ready for the game 48 hours away with the Utah Stars, the hottest team in the league.

“Zing the goddamned ball! You guys are going to be here till midnight!” Leonard is not known for his jovial practice sessions.

“Fist!” shouts Fred Lewis, using the code name for the next play. As he brings the ball up the court, he holds up a clenched right hand, which may be what it will take to right the flagging Pacers. They have lost three of their last four games.

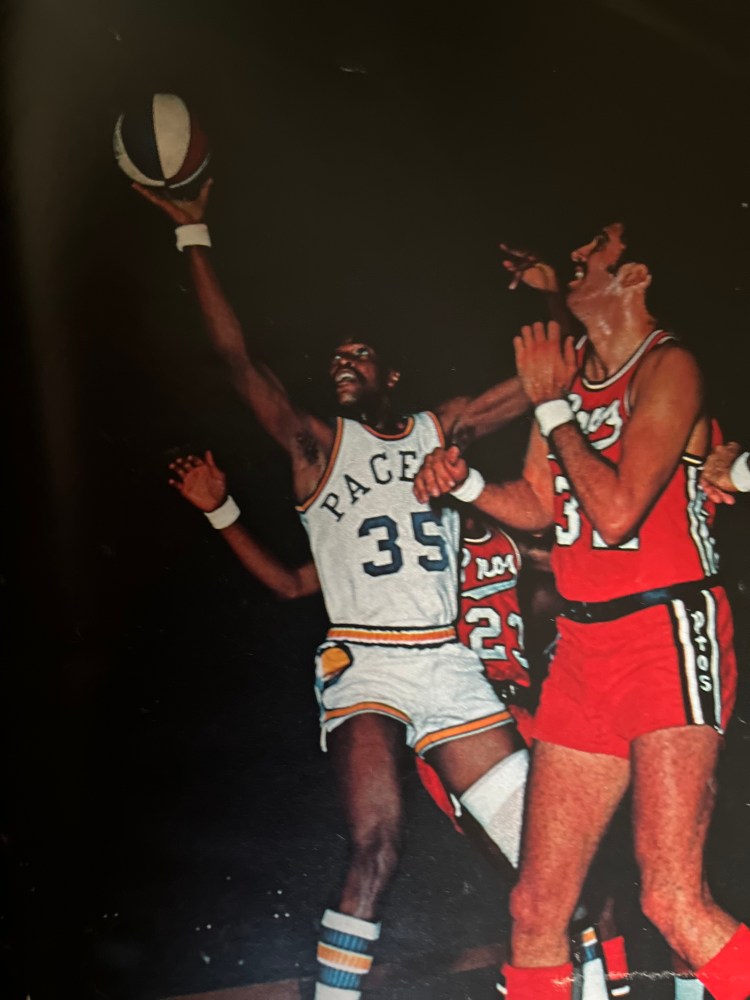

The guards start to weave at the top of the key. The third man to get the ball is 6-feet-5 forward Roger Brown. He puts the ball on the floor; dribbling is comfortable for him, but walking and running are not. Brown is trying to come back from a summer knee operation. The left leg is visibly thinner around the calf and thigh than the right. “It’s coming along,” Brown had said earlier.

He stops the dribble. Pacer center Mel Daniels and forward Bob Netolicky have set up a double pick on the right side of the foul lane. Bill Keller, the guard opposite Lewis, gets away from his man, and “fist” develops. It’s not a simple play; there is much motion and many options. This time, the ball ends up with Brown behind the double pick. In a moment he is in the air with a 15-foot jump shot. The ball is in the basket, but then pops out.

Coach Leonard, called “Slick” by his players, claps his hands with approval. “That’s it! That’s it!” He can’t make the ball go in the basket, but he can design plays which provide the Pacer shooters with good shots. In more subdued tones, he explains how “fist” will help deter Utah’s defensive ace, Wayne Hightower, from overplaying Brown. In Salt Lake City, two weeks before, Hightower had overplayed Brown dreadfully and had contained him. Hightower has also been scoring well this season.

“He hurt us something awful,” Slick reminds his men. That game was a meeting of unbeatens: the Pacers 6-0; the Stars 3-0. Now, the Stars are 7-0, while the Pacers are hurting. And the man hurting most is Roger Brown.

****

“What would you like?” says Brown after practice. “I just want to do it all again. If we can make happen, what happened last year, I’ll be perfectly satisfied.”

Bill Sharman, former NBA star and coach of the Utah Stars, knows what happened last year. Then the team was the Los Angeles Stars, and they lost the ABA championship to the Pacers in six games.

“In the series last year, he was extra-super,” Sharman said of Brown. “The last three games:53, 39, 45.” Sharman recited Brown’s scoring totals as if they were a beauty queen’s measurements. “And it always seemed like he’d come down and make that big play every time.”

Larry Creger, Utah’s assistant coach, added, “He rises to the occasion. That’s the key to Roger Brown. He’s a great player, but from what I’ve seen, he’s even better in the clutch.”

Sharman continued, “Roger Brown is the closest thing to Elgin Baylor when Elgin was at his peak. The way he handles the ball and shoots, his great ability changing directions and speed. One on one, he’s as good as there is. And he makes all those tough moves look easy. A lot of players can come down on a fastbreak and make an easy play look spectacular. You know, like a Maravich or even a Cousy. It’s fun to watch and you ‘ooo’ and ‘aaah.’ But Roger, like Oscar Robertson, will come down and make a real tough play, and do it so nonchalantly, that you’ll think it was an easy one.”

“And to top it off,” adds Creger, “he’s a great passer, too. Didn’t he lead their team in assists last year?”

That he did, as he has in each of the Pacers’ three years. In the league last year, Roger Brown was ninth both in scoring (23.07) and assists (4.2). And of the eight players ahead of him in assists, seven were guards.

****

“Oh yeah?” Brown smiles when he hears some of Sharman’s comments. But he doesn’t let the pleasure last very long. “Well, that was last year, and it’s over. Now is now.”

His concern for the present is a major facet of his personality; today he thinks about the next game and the leg. His knee operation was not a major one in that it did not repair structural damage. They took out a bursa, a sac below the knee cap, which is supposed to lubricate the joint. Roger’s was inflamed, causing friction and pain. Last year, he had frequent cortisone shots, though he played in each of the team’s 84 games and averaged 42 minutes. The operation was supposed to eliminate the need for more cortisone.

“But they gave me a shot last night anyway,” he says and looks over at the Pacers’ dapper trainer, David Craig. Craig smiles; what else can he do? Brown frowns. Then he looks at the knee and says again, “It’s coming along.”

When he went into the hospital in July, the Pacers released a description of the operation. “Another bursa will grow back . . . Probably the operation will prolong his career.”

Prolong his career . . . That is another of the bitter ironies of the man’s recovery.

****

His career had already ended once. Abruptly. Completely. Forever. The year was 1961. Roger Brown, the highest scorer in New York high school, basketball history, was finishing his freshman year at Dayton University. He had picked Dayton because it was good academically, and because it traditionally returned to New York for the National Invitation Tournament (NIT).

But in late May, he picked up a newspaper and read that he had been named, with Connie Hawkins, in a New York gambling indictment against a former pro basketball player named Jack Molinas. Dayton flew Brown to New York to testify.

“I suppose I should have taken a lawyer,” he told Indianapolis News reporter Dick Denny three years ago, “but I had nothing to hide.”

At the inquiry, he told his side of the story. (Brown cannot talk about details of the scandal now because he has legal action pending against the NBA. A similar suit was settled in Hawkins’ favor two years ago for over $1 million.) Yes, he knew Molinas. He spent time with Molinas while he was in high school. He and Hawkins and other players let Molinas buy them meals. He had no idea Molinas was any kind of gambler.

“Have you ever had somebody buy you something to eat?” Brown asked Denny. “That’s what I did. If I were to buy your meal now, would that mean you have done anything wrong?”

Later, the Brooklyn District Attorney issued a statement saying, his inquiries satisfied him that there had been no point shaving or other manipulation of high school basketball scores. But at the end of the school year, Brown was dropped from Dayton, suspended by the NCAA, and banned from the NBA. Without trial. Without even being charged with wrongdoing.

Instead of going to the NIT, Roger Brown went to work in a General Motors factory in Dayton. A Little later, he started playing amateur basketball twice a week. And sometimes, he’d go down to Cincinnati to watch guys he had played against in high school—Billy Cunningham, for one. Guys he thought he was as good as or better than. And they’d be down on the court, and he’d be up in the stands. It hurt.

He went on like this for six years. And eventually he began to make the rational adjustment to an irrational world. “I’ll always hold something back, and I’ll always have a shell,” he says. “If you look for the worst, you won’t get hurt so bad.”

His hurt made him hesitate when the ABA began to form. That day he signed with the Pacers, he went back to work the night shift at GM. Then when the Pacers’ training camp opened, he took a leave of absence from GM instead of quitting.

“I tried to protect myself all the way around, so if I didn’t make it in camp, I had the job to go back to. I had five years of seniority, and I didn’t want to throw that away for a chance that might fold in a week and leave me right back where I started.”

He’s been a starter for the Pacers from their first game, a win, in which he scored 24 points.

****

Three years later, it is gametime. Capacity at the Fairground Coliseum is 9,147, and a disproportionate number of those are bad seats. Tonight for Utah’s first visit to Indianapolis, all seats are sold, and there are 1,364 people standing as well.

The Pacers take the floor by bursting through a paper-covered hoop—the way they enter for every home game. Tonight’s Burger Chef Ballboy is introduced and presents the game ball to the referees. The ABA is still the gimmick league, no matter how good the quality of the basketball has become.

Roger Brown does not start. In his place is 6-feet-8 Art Becker, usually the Pacer sixth man. From the beginning, it is a hard-fought game. No one has a lead of more than six, and at the end of the first quarter, the Stars lead, 27 to 25.

Roger Brown starts the second quarter. His left leg is heavily taped. Only the patella peeks out from the narrow slit left to allow the leg to bend. As he takes his first trips up and down the court, it is painfully obvious that the leg is stiff and that he favors it.

Midway in the quarter, the “fist” play is called. Brown gets the ball and puts some muted moves on Wayne Hightower. He shoots, but his jump shot is short. The half ends, and the Stars lead, 53 to 52.

By the middle of the third quarter, Brown is moving more easily, but it is apparent his shooting is off. His jump shots tend to be short and, more significant, off line, which is very unusual for him.

With 1:40 to go in the quarter, the Pacers are down three points and need a basket. They clear out for Brown. The clear-out play is famous from last year. Coach Leonard says, “Last year, we won nine-tenths of our close ballgames, and a lot of the reason is because we had Roger Brown. When we needed a basket, we let him work one-on-one. He’d go for a good shot or pass off to another guy for a layup. He is a great pressure ballplayer and as good one-on-one as there is in the game.”

And Wayne Hightower has told me, “Roger has great moves to his right and good moves to his left. When he’s on, there’s not much you can do.”

Roger begins to work. There is no effort spared as he brings Hightower slowly toward the basket, but tonight it seems to be as much muscle as craft. Hightower is so close to Roger’s back that it looks like he is carrying a substantial fraction of Brown’s 208 pounds. It’s called overplaying, and tonight there isn’t much Brown can do about it.

About 10 feet out, Roger makes his move. There is contact; there are grunts. He goes under Hightower’s arm and gets off a left-handed shot from a few feet out. It caroms too hard off the backboard. The Stars rebound.

He has missed the shot, but it is clear that when it matters, Brown puts out. At the end of three quarters, the Stars lead, 75 to 72.

In the fourth quarter, with 10:10 to go, Brown falls hard, after tripping on the weave of “fist.” Timeout is taken. He has hit the kneecap of the weak leg, and it hurts like hell. He stays in the game.

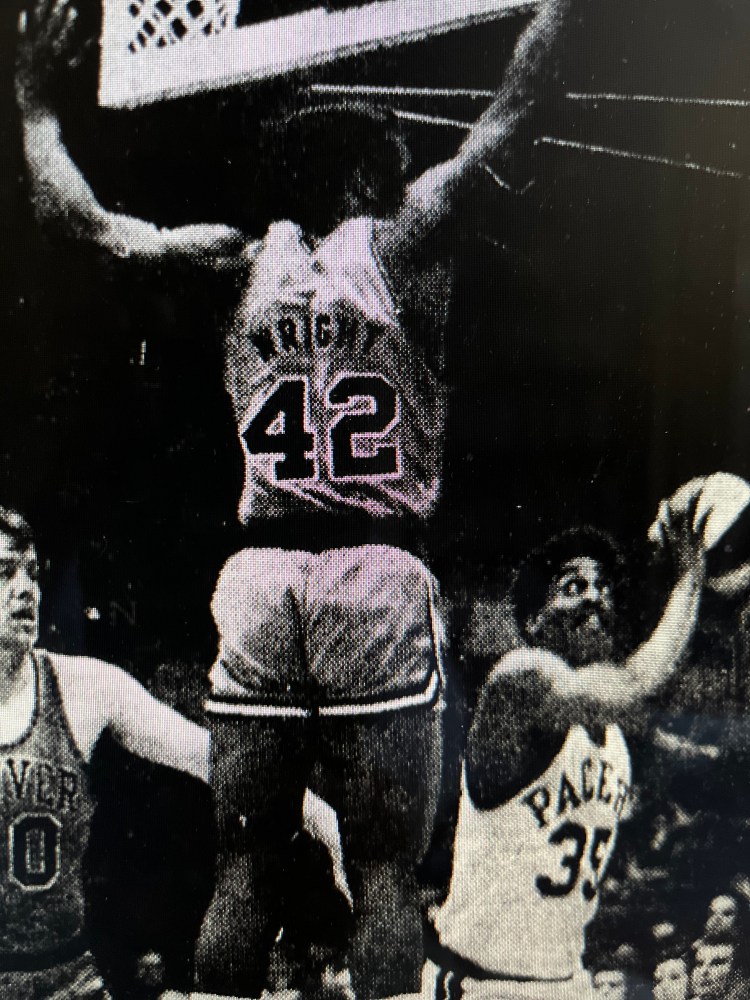

At 7:46, he hits a 15-foot jump shot to tie the score at 81. The crowd goes crazy. It is the first jump shot Brown has hit all night, and it came when it counted.

A Utah fastbreak rebuilds a two-point lead. Indiana comes back, and in a rebounding melee, Roger Brown ties the game again with a tip-in. The leg problem is no longer apparent. Brown crowds Hightower at the Utah end of the court. For perhaps three or four seconds, the players’ legs are making the same movements, step for step, as if dancing.

“Defense,” says Brown, “is more of a team thing. And when the team buckles down, it just becomes a matter of pride. It’s stopping your man from getting around you or making him go the way you want him to go.”

Hightower doesn’t actually get around. He twists and falls near the foul line and takes a shot, enough off balance to make any defensive man happy. But the shot drops. It goes that way for a team that’s winning. And for a team that’s losing? The Pacers have had innumerable close misses.

The rest of the night, the Pacers never tie the game again. They lose, 102 to 99. A hard game, and an extremely well-played one. Even Coach Leonard, who hates to lose, will have nothing but praise for his players. “We’re finally on the way back,” he says.

****

“What I do for laughs? That’s a question.”

Yeah, I guess it is.

“After losing, it’s kind of tough to laugh. When you’re winning, it’s easy; and it’s easier to start thinking about the next one. You still got to think about the next one. With a loss, it just takes a little longer. I thought we played a real good game, though.”

What do you do after a game?

“Usually, I go home and sit down a while.” He’s married and has a three-year-old son. “Or I might go down to Neto’s bar and have a beer to put the water content back.”

Brown gave up smoking when he joined the Pacers, and he doesn’t drink hard liquor. “Neto”—Bob Netolicky—is a close off-court friend, and they have a common interest. “Roger is a regular guy,” says Neto. “I’d say I’m closer to him than anybody else on the team now. I mean, a lot of these teams you’ll never see the black and white ballplayers together in the offseason. But Roger and me have kind of a hobby together. We, like, follow the police and spent a lot of time this summer riding in police cars.”

“I’m sort of a liaison officer with the department of public safety,” says Brown. “I take an active part in the city. I try to give what time I have to help some of the kids out of the streets, the guys who don’t have it.

“Indianapolis is a backward city, but it’s coming. And it’s got a lot of opportunities outside of basketball, which is what I’m looking for. I don’t have any specific ideas about what I want to do after basketball, but I do know that I want to be self-employed.” His own fate in his own hands; it’s not surprising he wants that.

No interest in coaching then?

“Coaching? Yeah. I really think I would. But I wouldn’t like that to be the only job I had. I wouldn’t want to have to depend on it.”

I ask now how he has improved in the last three years as a player. I point out that his field-goal percentages have improved regularly. He hit 43 percent his first year, 48 in his second, and last year 51, even though he took many more shots than in either of the previous years.

“I’d have to say, I’ve gotten a lot smarter in the game and a lot more confident,” he says. “That first year, I drove to the basket 80 percent of the time. But I found my shots getting blocked. Now, I pull up and shoot the jumper. Out of the forward slot, I think the most-important thing in the pro game today is knowing when to shoot. Now, when I go out there, I feel there’s no one I can’t score on, that’s the kind of confidence I’ve got.”

A fan and friend comes up to talk to Brown as I am asking about his problems being recognized. He says, “It’s just that you have to watch yourself at all times. Can you wait a sec?”

I amble down the row of lockers. Netolicky and Mel Daniels are sitting together, but not talking. Daniels looks like the world has ended. I want to ask him about the time he and Roger were getting sodas in Los Angeles from a machine which happened to be near a liquor store where the burglar alarm was going off. But then I stop and think better of breaking in on Daniels’ reflections.

“Even after they lose, you can talk to Roger,” I have been told, and it is true. Not because he doesn’t care about losing, but because of the nature of the man. He wants, but he wants only what is possible, and changing the past is not included.

“In college, they used to call me unemotional,” says Netolicky, “but Roger is in a class by himself.”

“I’ve seen him worked up maybe once or twice,” says Fred Lewis, who, along with Netolicky and Brown, is the other remaining “original” Pacer. “One time was last year during the playoffs against the Stars. He just took it upon himself. The game he scored 53 (an ABA playoff record), he was just phenomenal. Shots from everywhere, and mixing them up with his drives. And I think he had nine or 10 assists. He did it all.”

Case proved. He did it all. Now, the only problem is to do it all again. “Last year’s gone. But it’s a challenge, and I want to repeat it.”

For Roger Brown, now is now, and yesterday seems so far away.