[Our last post featured Norm Van Lier in the winter of 1978. While Van Lier reflected on his long tenure with the Chicago Bulls, neither he nor the reporter knew it all would come crashing to an end within months. In October 1978, right before the start of the next season, the Bulls cut loose the 31-year-old Van Lier, claiming it was time to rebuild around younger players.

The turn of events infuriated Van Lier. He later stated on the record about the Bulls, “I definitely hate the organization with a passion. I’ve given them all my life. You can’t count money for the sweat I’ve given them.” According to Van Lier, Bulls’ GM Rod Thorn had lied to him. “You know they didn’t let me go for a youth movement,” he seethed. “All the youth he said he’s going with, he let go,” pointing to short-time rookies Chubby Cox and Andre Wakefield.

Not true said Thorn. He and Bulls’ coach Larry Costello intended to make a point guard out of their tall, celebrated rookie Reggie Theus. The arrival of Theus made Van Lier and his then-hefty multiyear contract an albatross around the organization’s neck. Unmentioned, but ever present just below the surface of polite conversation, was the real crux of the issue: Van Lier wasn’t easy. Thorn knew it, so did Costello, and so did Chicago Tribune reporter Bob Logan.

In this feature, published in the October 15, 1978 issue of the Chicago Tribune Sunday Magazine, Logan offers a detailed look at the Bulls’ aging floor-leader about to open his 10th NBA season. Logan had known Van Lier for years, through the good times and the bad, but he understood the Old Bulls and Stormin’ Norman’s fiery brand of loyalty.

However, between Logan’s writing and his editor’s final red marks, this story ran just after Thorn and the Bulls unexpectedly cut “Stormin’ Norman” loose before the team’s home-opener against San Diego. Though ill-timed and focused on a 10th Bulls season for Van Lier that wasn’t, Logan’s profile is solid. It offers for posterity an important glimpse into one of the NBA’s more-complicated characters during the 1970s.]

****

Can he be Norman without stormin’? Can there be such a thing as the calm during the storm?

We’ll soon find out because the visitors with San Diego on their shirts won’t be the only thing new on the court next Friday night for the Bulls’ home opener against the Clippers. Thousands of pairs of eyes will then gaze upon the “new” Norman Van Lier III, at 31 still the Bulls’ playmaker, but now transformed, he says, into a mature, relaxed, peace-loving citizen who has drop-kicked his last scorer’s table.

“I understand so much more now, and I’m thankful for what I’ve been through,” Van Lier said before heading west with the Bulls to begin his 10th year in the National Basketball Association. “I can now face the ups and downs, all the pressure, with a cool head.”

Norm’s last two Chicago coaches figured that a new Norm would be a bigger surprise than the Bulls winning the NBA championship in 1978-79. Dick Motta’s requiem for the love-hate relationship he had had with his fiery guard was: “The consequences of his actions hurt his teammates, and I’d hate to trade him to a good friend. Van Lier and (former Bull forward) Bob Love were the kind of players who couldn’t win big games.”

Motta’s successor, Ed Badger, fled to the University of Cincinnati at the end of last season alleging that “Norm wouldn’t accept the same discipline that applied to everybody else; he’s always been an overachiever, and he can’t understand the fact that most NBA players are underachievers.”

Van Lier believes that the best defense against these allegations and the other hassles in his combustible career is defense. It’s hard to disparage the effort he and Jerry Sloan expended to make it clear to opponents that driving the lane was hazardous to their health. The two were perhaps the best defensive guard combo ever to play pro basketball.

At any rate, the stormy Van Lier has told the new Bulls’ coach, Larry Costello, that (a) his personal storm clouds have blown over, and (b) he’ll pair with 7-feet-2 center Artis Gilmore to provide the short-and-long of a team that will be an NBA title contender here and now. Stadium skeptics, however, recall when a nightly flareup was the norm for Norm, and they’ll be waiting for the next explosion to demolish those reform pledges.

And then there are the NBA referees, who all have drawn Van Lier’s ire at one time or another. Even the Bulls’ fans, failing to understand the background for his sometimes-listless offensive showings last season, booed the veteran for the first time in memory. The customers were disappointed, because they had come to expect a standard of excellence in the tossing of both opponents and tantrums during the Motta era (1968-1976), when the Bulls were the best football team in town.

The Bull wearing No. 2 was No. 1 at those crowd-pleasing antics. With Norman Van Lier III around, who needed World War III? And besides spreading his own portable mushroom cloud over the NBA, Van Lier was a central figure in the finale of Chicago’s own series—the annual summer swoon of the Cubs and the White Sox, followed by the Bears fumbling and failing to make the playoffs, and then by the Bulls’ making the playoffs but stumbling out of contention.

For the Bulls, surviving as a team was an uphill struggle. They finally booked reservations in the overcrowded Heartbreak Hotel of Chicago sports and bunked with the 1967 White Sox, the 1969 Cubs, the 1971 Black Hawks, and the (pick your year) Bears by folding like an undertaker’s chair in the 1975 NBA playoffs.

A compact 6-feet-1 and 175 pounds, Van Lier has a modus operandi on the court that forbids him to pick on anybody his own size. He specializes instead in putting half-nelsons on such oxen as 6-feet-9 Sidney Wicks, whose skull he almost massaged with a metal chair during a friendly tag-team match five years ago. Wicks will be here next Friday with the Clippers and not just to reminisce about the past with his old sparring partner.

That was Van Lier’s image in those exciting days. He was alleged to possess a hair-trigger temper, and the fans enjoyed watching a series of eruptions only slightly less predictable than those of Old Faithful. “A lot of people used to be afraid to speak to me, figuring I’d tear their heads off,” he marvels. “If they call you ‘Stormin’ Norman,’ I guess they expect you to act that way.”

****

Reality was a lot less exciting and a lot more complex. While Bull diehards were agonizing over their team’s demise on the doorstep of the 1975 final playoff, Van Lier was trying to cope with a painful divorce. His wife, Nancy, had walked out on him, and the playoff setback was a secondary burden in that traumatic year.

“I was hurt more over losing the woman than losing the championship,” Van Lier says. “I guess Nancy always will be the love of my life. Amazingly, I got through the season playing well, but when it was over, I went camping to get away from everybody for about a month and a half.”

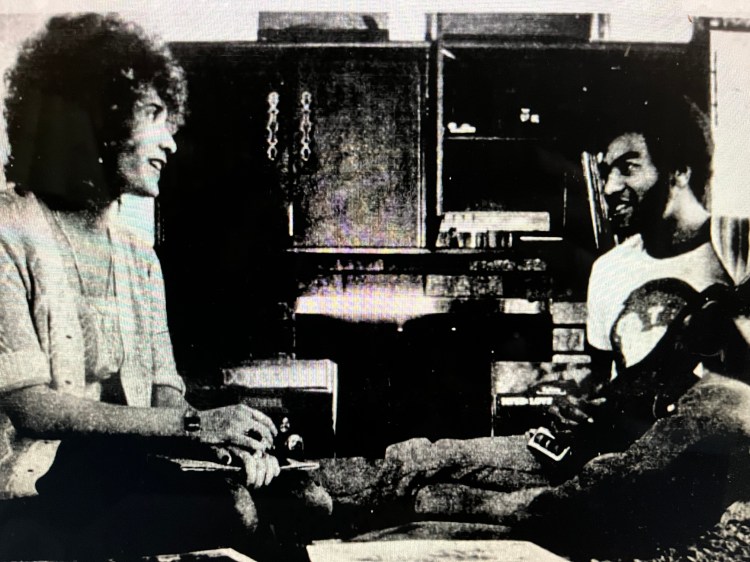

With time, some healing had come to his inner hurts. Now Van Lier sorts it all out in the den of his 19th-floor Near North Side condominium, which has parquet floors and an impressive lake view. Staring at the awards, plaques, and action pictures on the walls, he also touches on his playboy reputation.

“I live right around the corner from Rush Street, but you won’t find me out there because it’s not my type of world,” he says “When I got divorced, I had time to run around and get around. No use sitting at home in the place I lived a couple years with a wife.

“But since I bought this place, I’m at peace with myself. I never have been one to go to this bar, run to that place. Every now and then, I go out to be with the gang. You see me at ballgames, but I prefer a private dinner with a lady, and I have a better time going to the woods alone in the summer. I have a lot of associates and a few real friends.”

Last season was Van Lier’s first on a new five-year contract, which put him in a truly upper tax bracket for the first time, much later than many other NBA guards with less all-around ability. Now he earns close to $200,000, not far below Gilmore’s salary. But as things turned out, he paid a heavy price for that financial status.

Last year was a winter of discontent for the Bulls and their fans, with Coach Badger and playmaker Van Lier becoming increasingly alienated from each other while playoff hopes foundered. The Bulls had streaked down the stretch to win 20 of their last 24 games in 1976-77, hyping season-ticket sales for 1977-78 to an all-time high and boosting victory-starved Chicago’s expectations. When that giant rose-colored balloon was punctured toward the end of the 1977-78 season, hot air escaped with a deafening roar.

Before long, the Bulls were pointing the finger of blame at one another. Van Lier is convinced he got a dubious digit from Badger, who fingered the veteran guard’s scoring decline and reluctance to shoot as main factors in the team’s collapse. Becoming a villain in the stadium where he had been the resident hero for so long was a demoralizing experience. Already unhappy because Badger had tried to trade him in the summer of 1977, the Storm turned into a cloudy drizzle. And after the Bulls lost a last-minute nightmare to the Trail Blazers in Portland last January 3, Van Lier was greeted at home by boos that increased in volume as the team sank in the Western Conference.

“When I started getting booed, it took something out of me,” Van Lier admits. “I take all the beating I can because I want to win that bad, but we were not winning. It started after that game in Portland. I could handle that, but not on top of losing and getting my butt whipped on the floor every night. I lost it all.”

Van Lier concludes that, ironically, the 1976-77 season’s big finish, which packed the Stadium with hysterical crowds, was a major ingredient in the next season’s disenchantment.

“I could see guys going off in different directions, and some of them got complacent,” he explains. “When the team was ‘the Madhouse on Madison Street,’ that was fine. We proved we could win, but this time teams were ready for us, and we were too busy dealing with our egos instead of playing basketball. And when we were put to the test, we just didn’t have it. We were getting smacked in the face, shut down on offense.

“I’m glad it happened, if only to keep the egos back down where they belong. We didn’t deserve to win anything then. I was put in a position of being beat up while the rest of them weren’t ready to play and didn’t know what to do. If we’re not organized, I can drive to the hoop all night and it won’t do any good.”

****

The new Van Lier makes it clear that the old feuds are over—at least for him. “Understand, I have no animosity towards anybody on the team,” he says. “They’re a bunch of good guys, but from the coach all the way down to the last player—including myself—we did not have a damn thing going for us. We had guys who thought they belonged with the elite. Unless they come down off the pedestal—accept the fact that if they’re not hitting, we have to go to someone else—we won’t go anywhere. This is not my job. It’s Larry Costello’s job, just like it was Ed Badger’s job.”

The first open breach in the Badger-Van Lier line surfaced when Norm got sick on a flight to Boston last November 30 and returned home to be hospitalized for “flu and exhaustion.” He publicly blasted the Bulls’ system and privately denied rumors that his ailment might have been drug-related. “Nobody could play basketball with my intensity if that were true,” he said then. “I’m just plain exhausted from being run over by those big guards 40 minutes every night.”

There was one final effort, on January 8, in Denver, to patch up the team’s leaky hull. It backfired, however, and the hostility it aroused in everyone was reflected in the team’s lackluster performance.

Badger had asked Van Lier, the team captain, to talk to the troops, who were still in a state of shock from the Portland game on January 3, before they faced the Denver Nuggets. Posterity will not record his remarks on the same page as Knute Rockne’s “Win One for the Gipper” bit. Nevertheless, the Storm didn’t mince words, and he stirred up some resentment among his younger teammates.

“I didn’t cut anybody up,” Van Lier says. “All I told them was: ‘Hey, we’re not playing team ball, we’re ignorant of the plays. We need guys coming to practice on time and doing their jobs.’

“All I got from it was a lot of negative feedback without the coach backing me up after he had asked me to talk to them. I told Badger if it meant being put on the spot like that, I’d rather not be captain. To save face, they then announced that Artis was co-captain with me.

“We had been reading too many headlines after that good playoff series (in 1977) against Portland. When we were put to the test the next year, we just weren’t that good a team.”

Ex-coach Badger views things differently: “I inherited Norm as captain, so it wasn’t a matter of saving face,” he maintains. “It was a matter of putting the real team leader up there with him. Norm’s Norm, and he’s not gonna change. We missed the playoffs last season because we weren’t a championship-caliber team, not because of lack of preparation. I know it’s hard for him to understand that.

“In the old days, under Motta, the Bulls didn’t worry about anybody else but just about doing what we could do,” Van Lier fumes, warming to the subject. “I took all the blame and didn’t say anything. If I’m the scapegoat, that’s the way it’ll be. This is the first time I’ve spoken up and said what was going on with the Bulls. I like Ed, but his being a nice guy was not helping this team on the basketball court.

“Last year was the first time I fully realized how much of myself I’ve been giving up. I didn’t have a play for myself, not one, after all the sacrifices I made to get the ball to the open man. When my plays were taken out, I could see how much it hurt the offense. Wilbur Holland didn’t get a lot of good shots, unless I drove to the hoop and, as his man picked me up, threw the ball to him. At the end of the year, Mickey Johnson’s selection of shots was sour, because I was not playing full-hard. I was adjusting to the other teams saying, ‘Stop Van Lier, and you can cut this team off.’

“All I did was play defense and get my brains beat out. It became physical abuse of Norm Van Lier’s body, which wore me out mentally. I couldn’t play 20 minutes without tiring out. They kept saying the Bulls would bring in a big guard, but I was the big guard on defense against such players as George Gervin and Pete Maravich.

“If I didn’t get in there and make things happen, we don’t have much of an offense,” Norm says in a sudden switch to the other end of the court. “I’m a penetrator, so they can afford to sag on me. If I’m driving and they force me to one side or the other, that’s it. We had no options last season. Without fastbreaks and rebounding, I knew we were gonna stink the joint out. No system, no organized anything.”

****

Larry Costello saw all this last year as a roving scout for Houston before the Bulls’ general manager Rod Thorn recommended him to succeed Badger. Back in the Motta era, when Van Lier was a full participant in the team’s patient, plodding offense, Costello plotted Milwaukee’s zone press, which contained the Bulls better than any other team in the NBA. He always has been an admirer of Van Lier’s skills and plans to make full use of them this season.

“Norm’s gonna run our ballclub and hustle on defense like he’s always done,” the new Bulls’ coach says. “He’s the quarterback, but we must get more scoring out of him. It’s obvious something happened to the Bulls toward the end of last season; they just weren’t playing together. That doesn’t concern me now. Van Lier is a key man, and he told me he’s in a better state of mind to play basketball than he has been for years.

“I always thought Norm had great judgment on the fastbreak. He evaluates the situation, and if it’s not there, he’ll pull up and go into a pattern. That’s the kind of running game I want the Bulls to have—aggressive, but still under control. He’s the man who can make it go, but if he doesn’t perform, he won’t be in there.”

Norm Van Lier relishes the thought of reclaiming his former role as defensive hitman and offensive triggerman. “Under Costello, all the confusion will vanish,” he says. “He is a qualified man, not one just ego-tripping on the fact that he’s coaching in the NBA. Larry’s not the big- man-around-town type. He’s been through too much for that.”

While coaching Milwaukee to a 410-264 record through eight-plus seasons, Costello successfully melded Kareem Abdul-Jabbar with marginal supporting talent, winning an NBA title and falling one game short of another. He’ll be expected to produce an encore with Gilmore in Chicago, and Van Lier thinks it can happen.

“Maybe we don’t have the bench some other teams do, but we can hang in there. I can stick out in the running game that Larry wants because of my ability to make a lot of people happy. We have to build around Artis.

“Guards can help, but they can’t dominate. Only a center like Artis can do that. If we’re gonna win, the big fella has to make us win. I’m not trying to put pressure on him. This is the way it is in the NBA. Gilmore has the physical ability to be one of the greatest.

“I can’t look inside his mind to see if he has the mental toughness. He’s so quiet off the court, it’s hard to tell. All I know is it will take all of us to get the best out of Artis.”

****

Now that he’s past 30, Van Lier thinks he’s old enough to trust himself. Coaching may be in his future, though it’s just one of many possibilities, at least until the dust settles from all the storm clouds that have been raging around him.

“When it’s time to quit playing, I want to leave with a healthy body,” he says. “Watching Jerry Sloan hobble around for the last few years was like a caution light to me. Too many players like him have given everything they have to a ballclub, and then they get treated like cattle after they’re hurt.

“Sure, Jerry deserved the Bulls’ coaching job. I knew when they didn’t give it to him right away after Badger left that he wouldn’t get it.

“When a game was on the line, you couldn’t find a tougher player than Jerry. That’s why we had the most-important thing going for each other as teammates—respect. The Bulls had togetherness then. It was nothing for Sloan or me to give up a little skin to get the ball, because we had the type of dedication that’s so rare. A lot of guys with great bodies won’t dive on the floor. The CBS superstars, like Dr. J and David Thompson, make the slam dunks and get all the recognition. I’m known just for hustling, but coaches appreciate the little things a Norm Van Lier does.

“Maybe if I’d been drafted by the Knicks, I’d have been a different kind of Storm” he reflects. “My personality on the court, fits in with Chicago, going all out to give all I have. This is a fast, hustling city, even though it’s never been number one.”

Whatever its number, Chicago is a long way from Midland, Pa., where Baptist preacher Norm Van Lier I, his grandfather, settled from Kentucky, and Norm Van Lier III grew up. Soundly grounded in basketball fundamentals by Coach Hank Kuzma at Midland High School, young Norm chose to attend St. Francis College in Loretto, Pa., partly because Kuzma recommended the coach, John Clark, to him. It was a good choice, because Clark recognized major-league ability and taught Van Lier how to make the most of it.

“Norm, you can score or do anything you want on this level,” the college coach told his star. “Your main asset should be to keep everybody else happy by giving up the ball.”

Even now, as he prepares to join the select circle of athletes who’ve lasted for a decade at the top, Van Lier treasures that advice. “First of all, I was taught to respect my coach and my opponent,” he says. “If a young player can’t learn to do that, he won’t respect himself.

“I wouldn’t change anything that’s happened to me, except a couple of NBA championships. I’ve let things out that a lot of people would keep in, but I can’t go against the way I am.”

In that case, don’t take down all the storm warnings just yet. “Stormin’ Norman” Van Lier probably has a few more squalls to sail through and a lot more beefy opponents to sail into.

[As mentioned at the top, Chicago waived Van Lier before the season opener. Milwaukee quickly picked him up, but the Bucks waived Van Lier in January 1979. In February, Chicago fired Larry Costello, who said, “I knew it would be a great challenge, but I thought I could do it with Norm Van Lier, Scott May, and Tom Boerwinkle. But when I lost all three, there was no way.” Van Lier never played another NBA game. But he did make his peace with the Bulls, serving as the team’s radio analyst for many years. Van Lier passed away in 2009.]