[Before seven-foot Lew Alcindor rolled through New York City prep basketball in the early 1960s, there was Ray Felix at New York’s Metropolitan High. In the late 1940s, Felix was Gotham’s first seven-foot oh-my, though an extremely gangly one who didn’t come close to the skill and polish of Alcindor around the basket.

“I could have gone to UCLA,” remembered Felix, who was officially listed at 6-feet-11. “Jackie Robinson wanted me to go there. But I wanted to stay in the city, to play in Madison Square Garden, because I knew I wanted to be a pro. It was a mistake.” Felix enrolled at then-college powerhouse Long Island University, where the infamous 1951 point-shaving scandal derailed the basketball program in his sophomore year and sent him on his way. Felix spent his junior year playing YMCA basketball in New York, then moved to the semipro American League with the Manchester (Conn.) British-Americans, where he led his team to the postseason championship and emerged as the circuit’s “newest scoring sensation.”

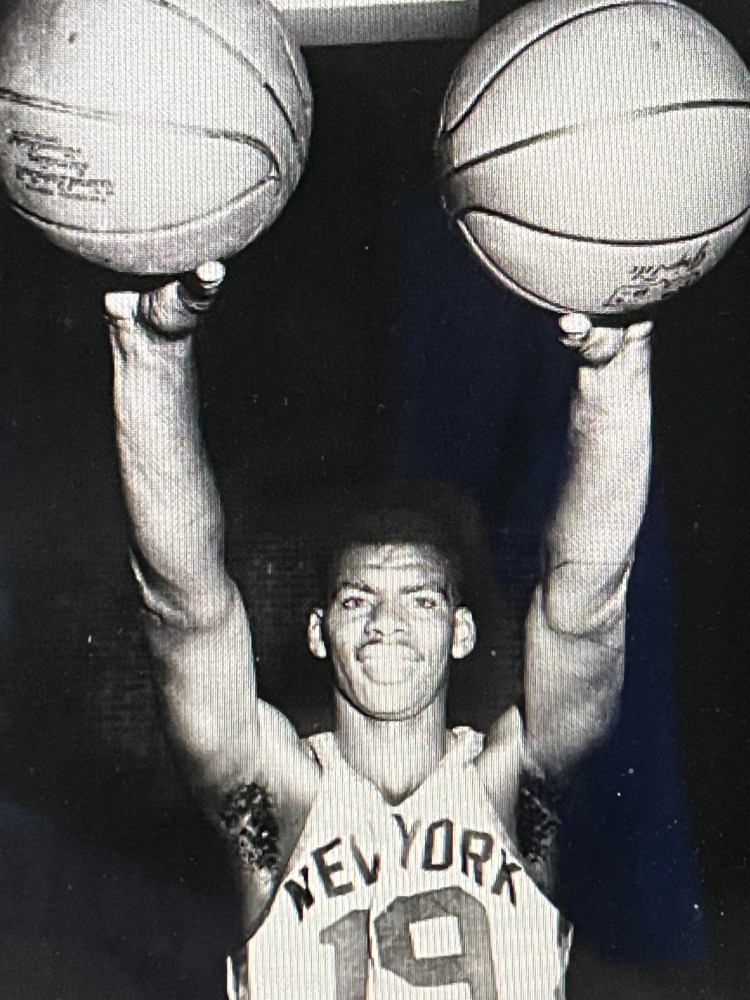

The Baltimore Bullets used its first pick in the 1953 NBA draft to secure Felix. Great pick. Felix flourished in his first season, appearing in the NBA’s midseason all-star classic and winning Rookie of the Year honors with 17.6 points and 13.3 rebounds per game averages. Baltimore, in financial quicksand and sinking fast, traded Felix the next season to the Knicks, where his career progressively languished tussling for rebounds and standing his ground.

“Besides watching [the Knicks] bow to Boston,” wrote the New York Daily News in December 1955, “[fans] got a gander at 6’11” Ray Felix, a 220-pounder, squaring off with 6’5” Jom Loscutoff, whose fighting weight is listed at 230. It was only a one-punch affair, but the Nw York stringbean was the smarter—he got in the one punch. It was a stinging jab, right on the mouth, that sent the Celt out of the game and will require several stitches inside his lower lip.”

By 1958, the latest NBA cliff notes on Felix’s career read: “He is the possessor of a hot-and-cold running hook shot. When he’s hot, Ray can be sensational, pouring in hook after hook. But then there are the nights when the hoop seems to have a cover nailed on it. “ In other words, the elongated Knicks center frustrated New Yorkers no end with his inconsistent play, rotten hands, and frequent fouls on several bad Knicks teams “Worthless,” his hecklers sometimes bellowed from the cheap seats.

Off the court, Felix was considered a gentleman and one of the NBA’s true good guys. In this childhood remembrance from feature writer Brian Moss, published in the May 10, 1987 issue of

the New York Daily News, the yin of Ray Felix the good guy image collides with the yang of Ray Felix the stumbling big man. Great story, and three cheers for Moss and Felix.]

****

When I was a kid at summer camp in Connecticut, learning how to play basketball, we used to run a drill called the Ray Felix. Actually, I don’t know if that’s what it was called officially, but that’s how I’ll always remember it. A bunch of us 6-and 7-year-olds would dribble through the legs of a giant man named Ray Felix while he stood, hands on his hips, in the center of Camp Everett’s outdoor asphalt camp.

Not a lot of people remember Ray Felix. He played with the New York Knicks in the late 1950s. And he was tall. I think he was about 6-10 or 6-11, but in those pre-Manute Bol days, that made him a 7-footer, and up till then that was about as big as any basketball player ever came.

I’m not sure how Ray found his way to Everett. A lot of the people who worked at that pretty little camp were teachers and administrators from New York City. Since Ray was a local kid who went to Metropolitan High and LIU before he went to the Knicks, maybe that was the connection.

However he got there, he tried to blend in as much as he could, considering he was a 7-foot Black man in a camp where the food was kosher and there were Sabbath services on Friday nights. He was friendly and not at all intimidating, despite his great size. I can close my eyes and still remember clearly what it was like to bounce a basketball through his shiny ebony legs in a snaking line of little kids in the hot summer sun. We didn’t even have to duck, that’s how tall Ray was.

So we looked up to him. And in time I became a Ray Felix fan. As fierce a fan, no doubt, as the man ever had. Every weekend that next winter, I would watch the pro basketball games on TV, hoping they would feature the Knicks.

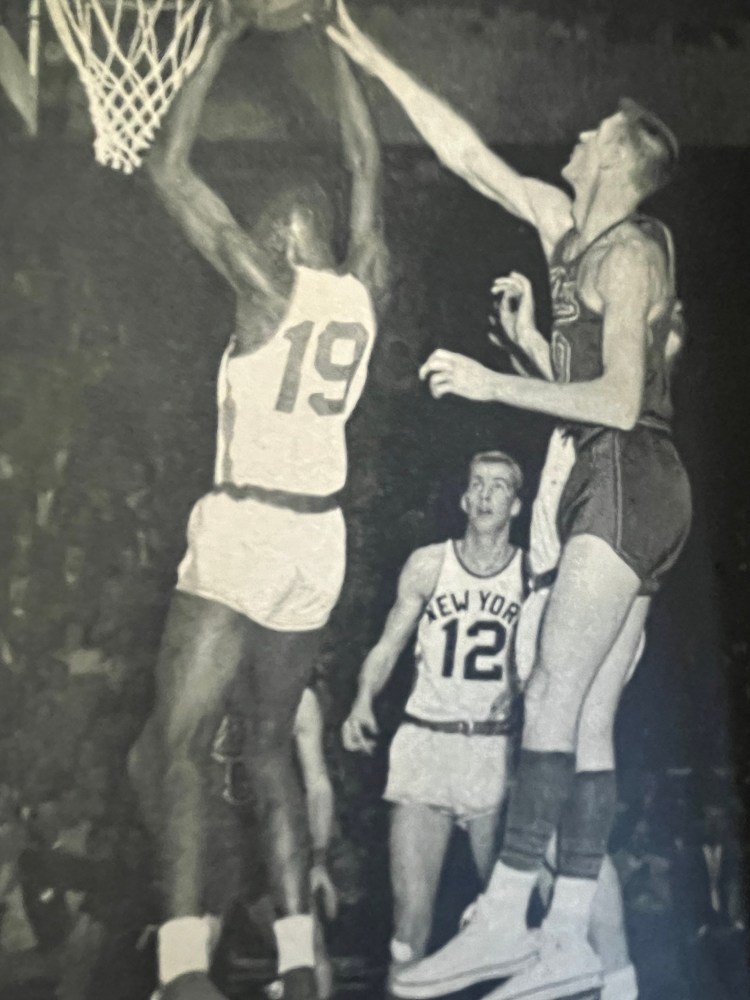

And sometimes they did. Unfortunately, it soon became apparent that they wouldn’t often feature Ray Felix. Ray, it turned out, was the kind of player who would substitute for a few minutes while some star player took a break. Half the time you couldn’t tell whether he was in the game or not, because the announcers didn’t bother to mention his name. And then, as soon as you figured out he was playing and you could fix your eyes on him, he’d be taken out.

The way I remember him is at the foul line. The camera would come in close, and he’d shoot and look awkward and uncomfortable. I wonder now what was going through his mind. I wonder if he knew how uncomfortable he looked. But this is all in retrospect. At the time, all I knew was that I was a Ray Felix fan.

Eventually, I wheedled my father into taking me to Madison Square Garden. My father, I think, tried to talk me out of the idea, for reasons that would soon become apparent, but I wouldn’t be stopped. I wanted to see my hero live and in person.

The Knicks were playing the old Philadelphia Warriors, whose star was Wilt Chamberlain. And it was Ray’s job, at least when he was in the game, to guard him. He did his best, I’m sure, but it wasn’t close to good enough. He was extremely outclassed. The boos and the taunts went all the way to the rafters.

I wish I could say that I yelled some words of encouragement, or that I stood up and cheered Ray Felix on. But I can’t. Instead, I sat quietly in my seat. When the game ended, my parents asked me if I wanted to go say hello to Ray. I said I didn’t think so.

Looking back, it didn’t bother me so much that Ray wasn’t a star. I had already realized that. What I hadn’t realized was that everybody else knew it too.

On the way home, I asked my parents if they thought Ray would ever be a star.

“What do you think?” my father said.

I said I guessed not. “Does that mean you can’t cheer for him?” he asked.

Before I could figure out the answer, my mother quietly joined the conversation. “Even the not-so-big stars need people to cheer for them,” she said.

It’s funny how you remember things like that.

And I just wanted to give Ray Felix a cheer. Go, Ray. I’m sorry it took so long.