[I spent my weekend inserting endnotes into my next book manuscript. At one point, I thumbed through the autobiography of the New York broadcaster Marty Glickman and happened upon the following story about the 1940s New York Knickerbockers:

“I had a ball with the Knicks. They were young, fun-loving guys, and I was still a young man in my 30s, so I was just one of the boys. One time, when we checked into a hotel in Washington, Lee Knorek, who was 6-foot-7, and 5-foot-11 Stan Stutz changed hats and coats. They were wearing black derbies, and black raincoats; Knorek’s elbows were sticking out of his coat, and Stutz was completely enveloped by Knorek’s coat. Knorek registered at the hotel as the Polish, Ambassador, and Stutz was his aide. They got into a nutty Polish conversation with a confused hotel clerk, demanding good rooms. The arguing that went on convulsed the rest of us.“

A few endnotes later, while flipping through a folder for a reference, I came upon another newspaper sports column about the aforementioned Stutz. What are the chances? So, I gave it a read and decided to pass it along. The columnist is the great Joe Falls, who entered readers for decades at the Detroit Free Press. His hail to Stutz, born Stanley Modzelewski (Falls will explain it all shortly), ran in the newspaper on February 21, 1967.

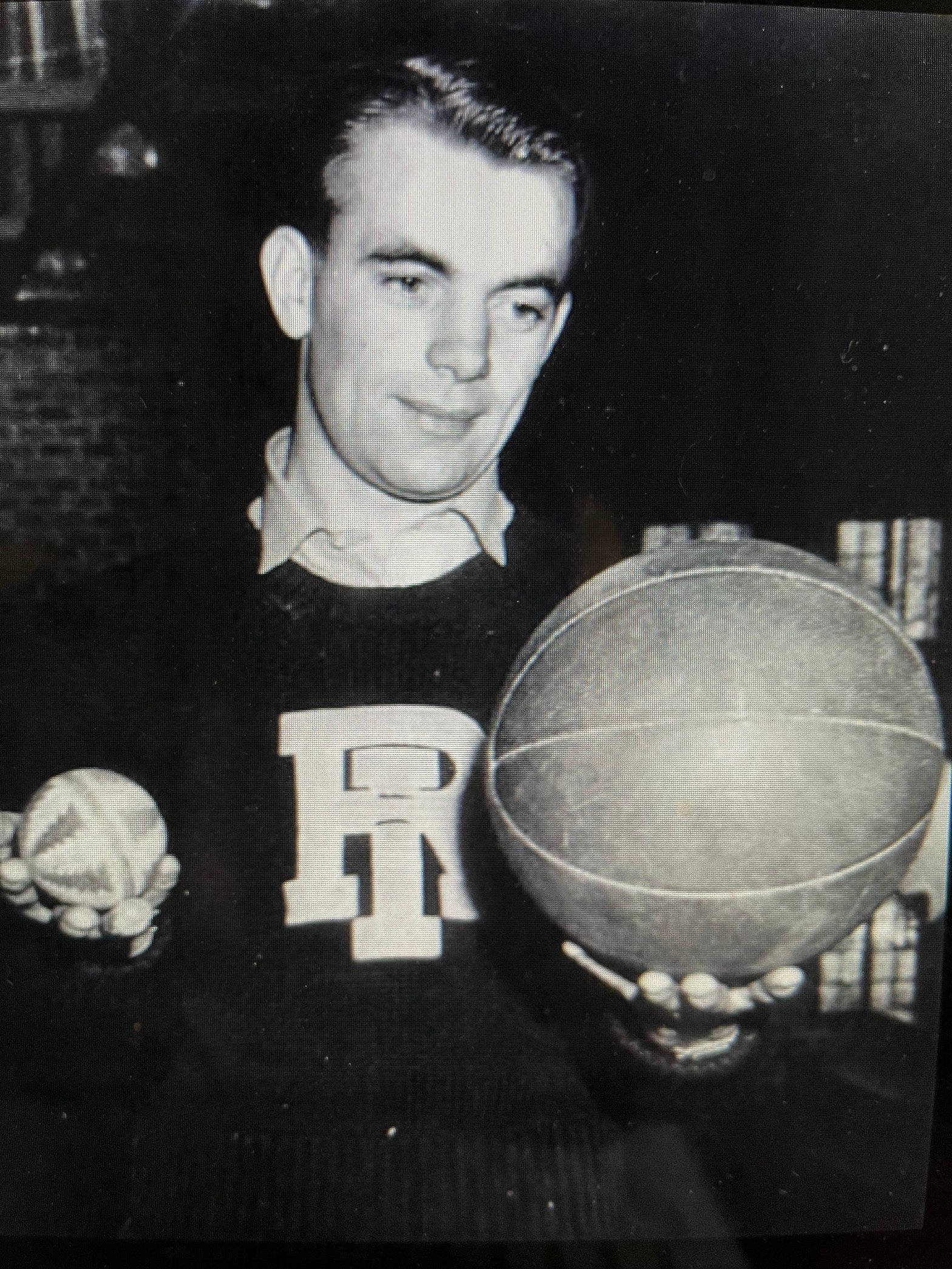

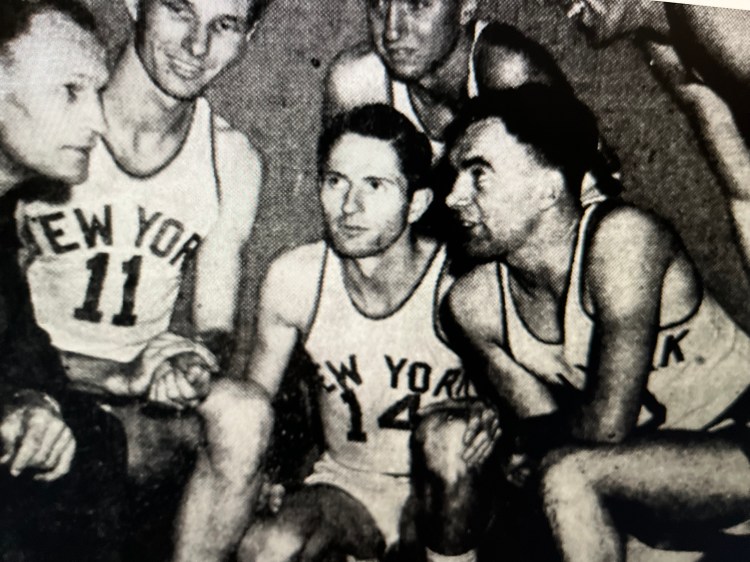

A quick blurb on Stutz. He was a three-time All-American in the early 1940s for the great Rhode Island State teams that energized college basketball with its high scoring night after night (Joe Falls will get there, too). Stutz, who set a national collegiate scoring record with 1,730 career points, graduated into the pros, where he led the Baltimore Bullets to the old American Basketball League (ABL) championship, then became a founding member of the New York Knickerbockers in the new Basketball Association of America (BAA). Known for his gutsy, gritty play that featured a flashy one-hand running shot (Joe Falls will get into that, too), Stutz starred for the Knicks for two seasons before dribbling out his final pro season with the BAA’s Baltimore Bullets. Stutz was always a fast-talker and a fast-mover until October 1975. That’s when, tragically, he had a massive heart attack that took his life at age 57.

Sure a gloomy way to end this intro. How about another wacky story from Glickman about the Knicks playing in the short-lived BAA city of Waterloo. It will you an idea of the basketball in Waterloo during 1947 (Joe Falls will explain that, too, further down)?:

“The early years of the NBA took us to some odd way stations. The Waterloo (Iowa) Hawks’ arena was heated by one huge hot-air blower situated near the ceiling at one end of the building. The blower was operated manually. All too frequently when the visiting team would shoot for the basket at the end where the blower was located, it would be turned on and a blast of hot air would hit the ball in flight. The ball would wobble like a knuckleball.”

****

If you want to know what’s wrong with the National Basketball Association—the repeated whistleblowing, the repetitious plays, the trials of traveling, and the constant carping of the coaches—don’t ask Stanley Modzelewski.

Don’t even ask Stutz Modzelewski. Or, even Stan Stutz.

He happens to think that the pro basketball of today is just fine, and this is surprising. Because if anyone has a reason to believe that the old days were better, it’s Stanley Modzelewski, Stutz Modzelewski, and Stan Stutz.

First, about those names.

He was Stanley Modzelewski in those early days in Worcester, Mass. He had this thing for Stutz Bearcats (which were the Jaguar XKE’s of the day, lads). And so, pretty soon everyone started calling him Stutz—Stutz Modzelewski. He liked it so much that he adopted the name legally and became Stan Stutz.

And how many of you in the audience remember when he was the greatest scorer in the history of college basketball, breaking all the records set by Hank Luisetti?

These were the days at Rhode Island State in 1940-41-42 when the rollicking Rams were rolling up the unheard-of total of 100 points a game. If the name Stan Stutz still doesn’t mean much to you—one of my colleagues is sitting across the desk saying, “Stan Who?”—he is generally credited with being the player who perfected the running one-hand shot. Luisetti originated the one-hand jump shot, but it was Stutz who added the wrinkle of throwing it on the run.

Twenty, 30, 40 years ago, all they ever did was shoot with two hands. The game was simple. You’d either play give-and-go and drive in for a layup or lay back and take a two-hand set. Nobody ever shot with one hand . . . at least not on the run. Except Stan Stutz. His coach at Worcester Classical High School was so repulsed by the idea that he kept young Stanley on the bench.

So here was our man at lunch at the Press Club on Monday talking about those good old days. “I guess I was a nut when I was a kid, but you know those tin cans, the kind that tomatoes used to come in . . . well, I’d get one of those and nail it to an egg crate. I’d stand the egg crate against the wall and shoot at the can with a tennis ball,” he said with a smile. “I got pretty good, too.”

So good that he shattered all of Luisetti’s records while leading the nation in scoring in his three varsity seasons at Rhode Island State. He went on to play pro ball with the New York Knickerbockers and Baltimore Bullets, and later refereed nine years in the NBA. The reason all this came about, this noon-time gabfest, is that we did a program piece for the Pistons about the old days in New York when the Knickerbockers of Sonny Hertzberg, Ozzie Schectman, Hank Rosenstein, Ralph Kaplowitz, and Nat Militzok were the love of my life.

One of the things that impressed me was the wild, one-handed shooting of Stan Stutz, “who had that sallow complexion and would comb his light hair straight back and take one-handers from all over the court.”

It was pointed out in the article that Stutz went on to become a ref in the NBA, and maybe this explained something about Stan Stutz. So, he read the article, so he called on the phone, so he flew in from New York on business, so now he was buying my lunch.

“What gets me,” he was saying, “is that our coach at Rhode Island, Frank Keaney, perfected many of the styles which are so popular today, and nobody ever remembers it. The zone press. We were the first team to use it. We pressed for the whole game. And the run-and-shoot style that’s so popular today—again, we were the first to do it.”

But this is the man who doesn’t live in the past. He thinks the game is better than ever. We played more of a chess game in the old days—don’t take a shot until you had a good one,” he said. “Today the shooters are fantastic. Look at the Celtics. They’ll bomb the basket five, six, seven times in a row, and do you know why? They know they’ve got a chance to get the rebound. So why not keep putting the ball up? It‘s sound basketball.”

I asked him about the refs, always a sore point in the pro game.

“They’re very good, very competent,” he said. “You’ve got to be hard-nosed to be a referee today, and the officials they have are this way. They can make good money, at it, too. That’s the big thing.”

Stutz told a story about the time, the NBA was a 17-team league, and he had to officiate a game in Waterloo, Iowa. “The only way you could get there was to take a train to Tama, which was an Indian reservation, and then wait for a guy to come by and drive you into Waterloo. You gave him five bucks.”

In those days, Waterloo’s big player was Harry Boykoff, the giant from St. John’s of Brooklyn, and this night Waterloo led all the way before the Anderson Packers pulled the game out in the final seconds. The crowd was so incensed that it spilled onto the floor, and the players of both teams had to lock arms in a circle to get Stutz off the floor.

As he was leaving an hour later, a tall blond woman with glaring eyes blocked his way. She stood in the tunnel leading out of the arena and pulled out the lipstick from her bag and spat at him: “I ought to mark up your whole face.”

“I don’t know where I got the courage, but I pushed my way past her. I thought it was going to be a bad scene,” said Stutz. “I met her a few years later at a party in Chicago, and she recalled the whole incident. It turned out to be Harry Boykoff’s wife, of all people.”

Stutz shook his head. “The old days weren’t too bad either.”