[It was during training camp, September 1962, that Harry “The Horse” Gallatin finally had seen enough. The new head coach of the NBA St. Louis Hawks called over his second-year guard Cleo Hill and told him, “there isn’t any point in going any farther.” Hill, the team’s “controversial” first-round draft choice from a year ago, was being released. Gallatin shook Hill’s hand and wished him good luck catching on with another NBA team.

But no NBA teams ever called. Three weeks later, Hill found himself trying to catch on with the Camden (N.J.) Tapers of the failing American Basketball League. “We haggled over the phone, and they said if I’d pay my plane ticket from St. Louis to Camden, they’d pay me the same salary I got with the Hawks.” Hill said. Hill’s gig in Camden would be short-lived, and many around the NBA started whispering: Why isn’t the immensely talented Hill playing in the NBA?

That included Paul Seymour, the former Hawks coach who drafted the six-footer out of college and was Hill’s number one booster (probably to Hill’s detriment). “I called Detroit, and they were supposed to get him,” Seymour said after Hill’s release. “But they never called me back. I don’t know if (St. Louis owner) Ben Kerner could keep Cleo off anyone else’s team, because the owners usually say to hell with each other and try to get a winner any way they can. But it is strange no one took Cleo.”

Sixty-plus years later, you still hear the name Cleo Hill used in sentences that include words such as “strange,” “tragic,” “blackballed,” “conspiracy,” and “racist.” Which, if any, of these words are accurate? Let’s take a look. You make the call.

What follows is a quick run through Hill’s short pro career, starting with an article that ran in the Winston-Salem (N.C.) Journal newspaper on January 29, 1961. Or right in the middle of Hill’s senior season at Winston-Salem State Teachers College, a small historically Black school hardly known for producing future pros. The article evaluates whether the flashy, high-scoring Hill is right for the 1961 NBA. Doing the evaluating is white sportswriter Bob Cole, who clearly is enamored with Hill and his game.]

****

On a wall of Cleo Hill’s dingy dormitory room at Winston-Salem Teachers College are pictures of professional basketball’s great Black stars . . . Wilt Chamberlain, Elgin Baylor, Bill Russell, and Oscar Robertson. In Cleo’s mind—and in the minds of Teachers College basketball fans—is the question: “Can Cleo, great as he has been in college, play with the pros?”

Last year, Cleo wasn’t considering a try at pro basketball; he would have settled for a place on an AAU team. However, he has since gained a new, more wholesome, self-confidence. He has matured as a basketball player and as a person. While he has much room for growth in both areas, he has at least overcome the lavish eccentricities that have limited his growth.

It would be to Cleo’s advantage, if he also could grow in physical stature. He is only 6-feet tall, and the National Basketball Association is probably the only place outside Sequoia National Forest, where a 6-8 man would feel insignificant because of his height.

Offsetting Cleo’s lack of height is his shooting skill and his uncanny jumping power. He has the bounce of a trampoline, and there is hardly a game in which he doesn’t dunk the ball through the hoop or block a shot off the backboard.

His scoring average through his first 15 games this season was 26.6. He had countered 155 of 337 field-goal attempts—a 45.9 percent accuracy, which would be excellent even if most of his shots weren’t calculated heaves from behind the foul circle or weird hooks and pivot shots from the tangle of the foul lane.

Still, Cleo’s potential is hard to assess for two reasons:

- The erratic, uninhibited league In which he plays—the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA)—defies evaluation. The CIAA presents at different times, and sometimes at the same time, a playground, Globetrotter, or pro-type basketball.

- In condescending to this unwanted level of competition, Cleo rarely shows more than a suggestion of his true talent. Still, he is the league’s dominant figure, and almost any team will sensibly concede him 25 to 40 points.

These concessions are a great change from past seasons when Cleo usually had two or three escorts wherever he went on court. But then, the new Cleo is a complex of changes:

- No longer does he wear his shin-length cuffless “continental” pants. Now he’s a herring-bone tweed (well-worn) man, with plain brown accessories. (“They said I wore those high pants for attention,” Cleo recalled poutingly. “I never [did that]. They were comfortable. But one day I saw my reflection in a store window, and I said, ‘Oh my. . .’”)

- No longer does he carry his own gym clothes from class to class. Now, he has other friends. (“I found I had to come to the local guys. They weren’t comin’ to me. They think the out-of-state fellows feel superior.“)

- No longer is he so self-conscious of his educational shortcomings. He has digested the vocabulary he swallowed whole to affect some intelligence.

- No longer is he so envied by his teammates, and no longer does he assume they are fortunate to play with him.

- No longer is he in conflict with his coach, C. E. “ Big House” Gaines, who, strong personality that he is, patiently weathered Cleo’s early impudence.

A friend, who had helped along Cleo’s high school and college rival, Al Attles, also helped Cleo in this area of attitudes. The friend merely pointed out to Cleo how a “good attitude” had helped Attles get to the Philadelphia Warriors, and Cleo “got de catch,” as he says.

Consequently, Cleo is—when he feels the opposition worth the sweat—making a creative effort to prove he is an all-round player, not just a gunner as some say. ”They say I can’t play defense,” Cleo began in his defense. “But I know defense so well I’m overlearned. But you just can’t do your best when you’re playin’ some of these guys.”

Against the poor opposition, Cleo, a front man on the Rams’ zone defenses, generally assumes a pretentious, wooden windmill stance, waves as an opponent drives by, then drifts back toward his own goal, hoping for the long pass and easy shot. He does not feel conspicuous in practicing this old habit in the CIAA.

Against those he considers nearly his equals, Cleo shows he can be a rebounder and as agile and harassing as any backcourt defender. Cleo has more talented teammates this year than in past seasons, and his confidence in them has relieved him of the pressures of being a one-man team. “We still like each other,” Cleo said, noting a great change from last year when New York Knickerbocker scout Red Holzman observed that Cleo would be a better player if his team wasn’t playing against him.

Cleo opened a recent game by banking in a hook shot from about 30 feet out on the right sideline, but shot only five times in the second half, preferring to cleverly feed his teammates. He admits he wouldn’t have played this type of game last year. And he still puts a premium on his passes:

“I won’t throw to a man jus’ because he’s open. I know what our players can do, and if one can’t score, he’s not getting’ the ball from me.”

Cleo has been called a “playground ballplayer” for such practices, the implication being, that he couldn’t run the game in more serious competition. None of this detracts from his achievement in college, however. He’s the youngest of six children from a Newark, New Jersey, tenement family, and not too long ago he missed some meals along with some baskets.

After four years at Teachers College, he is a little more defensive on the court, but more to his advantage, he is much less defensive off-court. Which would make it seem that the important question is not whether he can play with the pros, but whether he can meet that challenge without a loss of the hard-gotten poise that he now possesses.

[St. Louis drafted Hill in the first round of the 1961 NBA draft, eighth pick overall. It was, in NBA-speak, a terrible “fit” for Hill, who appeared in 58 of 80 games in his rookie season (he did miss time with an injured foot and fell out of the rotation). He averaged 5.6 points per game, shooting 34 percent from the field, and struggling on defense, bad foot and all. Take this clip from November 1961: “Hill was pitted against the toughest backliner the game has ever known, Bob Cousy. And the Cooz humiliated him. After determining quickly early in the game that Hill presented no defensive threat, Cousy dominated play as the Celtics rolled up a long early lead.” Hill also struggled to clamp down Sam Jones, Cousy’s backcourt mate. But that was life in the NBA for any rookie, not only Hill.

Up next are comments from several people who interacted with Hill during his rookie season. The comments are pulled from various books and newspapers (happy to provide the references, if requested), and they’re woven here into a narrative. The quotes come from Hawks’ players Al Ferrari, Lennie Wilkens, Si Green, Cliff Hagan, and Bob Pettit; Hawks’ general manager Marty Blake; former Hawks coaches Paul Seymour and Fuzzy Levane; and Hill’s college coach Clarence “Big House” Gaines.]

Al Ferrari: “The problem with drafting Cleo Hill began and ended with Coach Seymour, who was quoted in the local newspaper saying, ‘Hill is the guy who can lead us out of the wilderness.’ We players went crazy. We had just won 51 games, gotten to the finals again, and stretched the powerful Boston Celtics to seven games just a year before, and this kid needs to lead us out of the wilderness? Seymour had set this kid up to fail. The story created a bad atmosphere around the team.”

Cliff Hagan: “Cleo Hill was Seymour’s guy, and he had put all his chips on this player coming through. We still had Johnny McCarthy, Si Green, and, of course, a young budding star in Len Wilkens [in the military for most of the season]. But he wanted Hill in the top group, and I never understood why. He was a guard, and a guard’s got the ball all the time. I mean, he must have thought he was the second coming of Bob Cousy—which he wasn’t.”

Bob Pettit: “Seymour began pushing Hill from the first day of camp. He would say to some guard—Ferrari, for instance—‘Watch how Cleo dribbles, and you might learn something.’ This made Al so mad, he was ready to tear the place down because he was fighting for his job, and he was a good basketball player and a tremendous competitor.”

Al Ferrari: “Hill was not the brightest kid on the block, nor was he a great player. Seymour tried to make him a great player when he just couldn’t play at this level. He was a great small-college player who couldn’t cut it in the pros.”

Big House Gaines: “I have come to realize that Cleo was one of the most scientific players I ever encountered in my whole career . . . Most kids loosely aim and toss the ball, hoping that it will go in the basket. Cleo was figuring angles, distances, velocities, trajectories—doing all kinds of complicated math and geometry in his head to make sure it went into the basket.”

Bob Pettit: “Then Seymour might go to another guard and say, ‘John, that Hill can shoot. You can learn something from him.’ This made our guards mad because Cleo was practically handed the starting job right from the opening day of camp.”

Big House Gaines: “Immediately problems occurred with the established team members. Cleo was a Black star from a Black college team who was accustomed to playing fast break basketball. The Hawks front court was composed of three white veterans—Bob Pettit, Clyde Lovellette, and Cliff Hagan—who were accustomed to playing a slower game and doing all of the scoring for the team.

Si Green: In St. Louis, we had a lot of set plays, and they all ended up with one of the Big Three shooting. They made the money, and I set the blocks. There was one way you could score if you played guard—steal the ball on defense and get down the floor before they did.”

Big House Gaines: “The contracts for those three were structured such that they made more money if they scored more points and kept their scoring averages high. Then Cleo came on board and . . . shot and made baskets, which naturally cut down the numbers for the front three. If Cleo’s play kept up, they would make less money over the course of the year.”

Si Green: Seymour wanted to run. He wanted the guards to score more, too. He put Cleo Hill in the lineup. Hill was fast, he could shoot. But the Big Three didn’t want Hill. They wanted someone who’d give them the ball. They’d been stars, doing all the shooting. They didn’t want to run.”

Marty Blake: “Cleo went at one speed, and unfortunately our players couldn’t keep up with him. Bob [Pettit] couldn’t run, and Hagan couldn’t run, and Cleo couldn’t pass.”

Lennie Wilkens: “This kid named Cleo Hill had 20-something points [in his first game], but he also always had the ball. I heard the players were upset even to the point that Seymour had to fine a couple of them for supposedly not passing the ball to Hill.”

Bob Pettit: “Lovellette and Larry Foust got hurt, and everything started going to pot. We just kept losing. Paul [Seymour] was still pushing Cleo, and that was doing our morale no good. So one night I went to him and said in confidence. ‘Paul, this may be none of my business, but I am captain of the team, and I’d like to get this off my chest. I feel if you leave Cleo alone and don’t push him so much, he will work his way into our lineup and be a big help for us before the years out. I think he is being pushed too fast, and the others—particularly the guards—resent it.’” Paul said, ‘Bob, you’re probably right. I never thought of it that way . . .’

“That was the last I heard of that until we went into Detroit and Paul told the press he would trade any of his ball players, with no exception. It was an evitable now that he would clash with Mr. Kerner,” the team owner.

Paul Seymour to Kerner: “Cleo will break his neck to help us. If the other guys will give him half a chance, he can be an asset.”

Bob Pettit: “Later on, I heard Paul had been fired, but I didn’t know too much about it. The next day I picked up the paper and read his statement. The reason he had been fired, he said, was that he was taking up for Cleo Hill and some of the veteran players resented it. He said he wouldn’t dream of treating a dog the way Pettit, Lovellette, and Hagan treated Cleo.”

Fuzzy Levane (Seymour’s replacement): “Cleo was so anxious to get rid of the ball, fearing he’d be accused of taking too many shots, that he was hurting us the other way. I finally called a time-out and told him that if I had confidence to put him in the game, he’d have to have enough confidence to do things. He was playing scared pool.”

Big House Gaines: “Had Cleo been given a fair chance to compete in the NBA when he broke into the pro game in 1961, he may have become the first Michael Jordan—20 years before the Michael Jordan came along.

Marty Blake: “He came into the league with abilities that were 40 years ahead of his time.”

[Hill was released on September 12, 1962. Two days later, sports columnist Robert Burnes (famously pictured smoking a pipe) tried to explain Hill’s release to Hawks nation in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. Burnes clearly knew his way around the Hawks’ front office and repeated its storylines.]

Quietly and unobtrusively, Cleo Hill and the Hawks parted company this week. There will be criticism of this move by the Hawks, and they know it. In the eyes of some fans, Cleo Hill became a martyr last season. The Hawk management is aware of that, too, and because of it actually leaned over backwards to give Cleo every opportunity in 1962 to make a ball club for which he had carte blanche in 1961.

The toughest part of all of this is that Cleo Hill was an unfortunate victim of circumstances, and something like this shouldn’t happen to a nice kid who wound up badly confused. But it wasn’t the Hawks’ fault either that he wound up a poorer basketball player than he was in college. Since the primary idea in professional sports is to build the best and the toughest team possible, Cleo still was on his own in the matter of trying to make the ball club.

Two weeks of tough practice, convinced Coach Harry Gallatin that Cleo couldn’t make it. Gallatin had no part in the problems of last year, because he wasn’t the coach at the time. He was often an observer a year ago, but he came to camp with an open mind on every player. In case you haven’t noticed, up to this point Gallatin has not committed himself on a single starting assignment. That he is reasonably sure of some, of course, may be conceded. But he hasn’t said so, and he’s letting the players convince him.

Hill was given the opportunity to convince, and he couldn’t do it. The climax came early this week when Gallatin was sending the units through some simple inside weaves. Hill failed to work into the pattern several times and finally said, “Coach, I just don’t get the hang of it.”

Gallatin then suggested to Hill that the time had come to part connections. “If Cleo can’t fathom this simple routine,” Gallatin said, “there wasn’t any point in going any farther.”

It has been said here and elsewhere, not only in connection with Cleo Hill but with many other athletes as well, that the absence of a farm system is pointed up by situations such as this. Many of the National Basketball Association officials had hoped that the American League would succeed as a secondary loop to which players could be sent for seasoning. Certainly such players as Nick Mantis and Chuck Curtis, now with the Hawks, are better performers because of the competition they enjoyed in the ABL.

Cleo Hill had certain remarkable talents as a player. He had fast hands, a wonderful asset for a basketball player. He was quick. But his quickness and his hand speed were wasted when they weren’t harnessed with the team effort of everybody else. It is something a man might learn in a minor league but has to be taken for granted in the majors.

All of this worked to Hill’s disadvantage. So did the fact that he became the innocent pawn in a battle between the Hawks and former coach Paul Seymour. The matter involving Hill is a simple one in essence but had many complex ramifications.

From the day Slater Martin retired, the Hawks were in trouble on the back line. Every offensive move was directed to the Big Three up front, Bob Pettit, Cliff Hagan, and Clyde Lovellette. This worked to an extent, but a smart team, like Boston, merely dropped its two guards back, making it a five-on-three coverage of the big men. The Celtics dared Hawk backliners to shoot. Other teams hit upon the same solution.

Lenny Wilkens, half way through his freshman season, gave the Hawks a big lift in this situation. Seymour felt that one man wasn’t enough of a threat on the back line. He wanted two. There were some of us who suggested you couldn’t have five scorers, but Seymour answered, “There isn’t any rule against it, is there?”

With Wilkens in service last year, Hill was assigned the number one shooting and scoring slot. He was spectacular early, but team play quickly fell apart. Seymour and the Hawks, after many problems, only some of them relating to the back line, parted company.

Hill had to realize that he was indirectly (although innocently) involved. It shook his confidence. Fuzzy Levane, who replaced Seymour on an interim basis, sensed the situation. While Fuzzy didn’t accomplish much last year, we were tremendously impressed by his all-out effort, mostly in private conferences away from the view of the fans, to rebuild Cleo’s confidence. Late in the season, Fuzzy said sadly, “I just can’t get through to this boy.”

The Hawks brought Cleo’s college coach, Charles “Big House” Gaines to St. Louis for 10 days in midseason, trying to snap him back. But even Gaines admitted he couldn’t get through.

Hill was given every chance to make the ball club this year. He failed as hundreds of other athletes have. It’s a part of the game no one likes. Coaches and managers in every sport tell you the toughest job they have is breaking the news to an athlete. But it’s the way the game is played.

[Finally, we move ahead to 1969. The Winston-Salem sportswriter who started us off, Bob Cole, has relocated to Philadelphia and a new job and profession. But Cole still marvels over being there to see Hill bank in his amazing 30-foot hook shots for Coach Gaines. Neither did he forget the amazing kid who followed in Hill’s footsteps at Winston-Salem State: Earl Monroe. Here, Cole compares the two “playground players” and tries to explain their different NBA journeys. Cole’s freelance piece was published in the Winston-Salem Journal on February 12, 1969.]

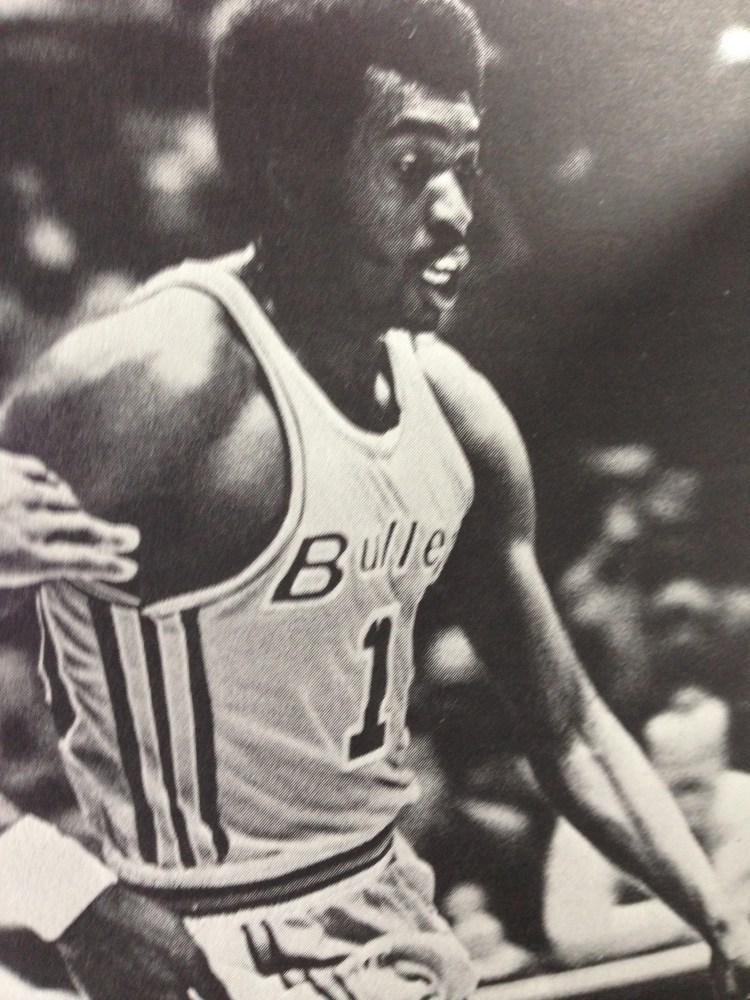

Maybe Earl Monroe got to where Cleo Hill was going. Their basketball careers started the same, and, given more friendly circumstances, both—not just Monroe—might now be stars in the National Basketball Association.

Both men dribbled and dodged out of the mean streets of the North—Hill from Newark, Monroe from Philadelphia—and became the two best-known players that Winston-Salem State College ever had. From that relative obscurity, each was selected in the first round of the NBA draft of college players. There, the similar experiences end.

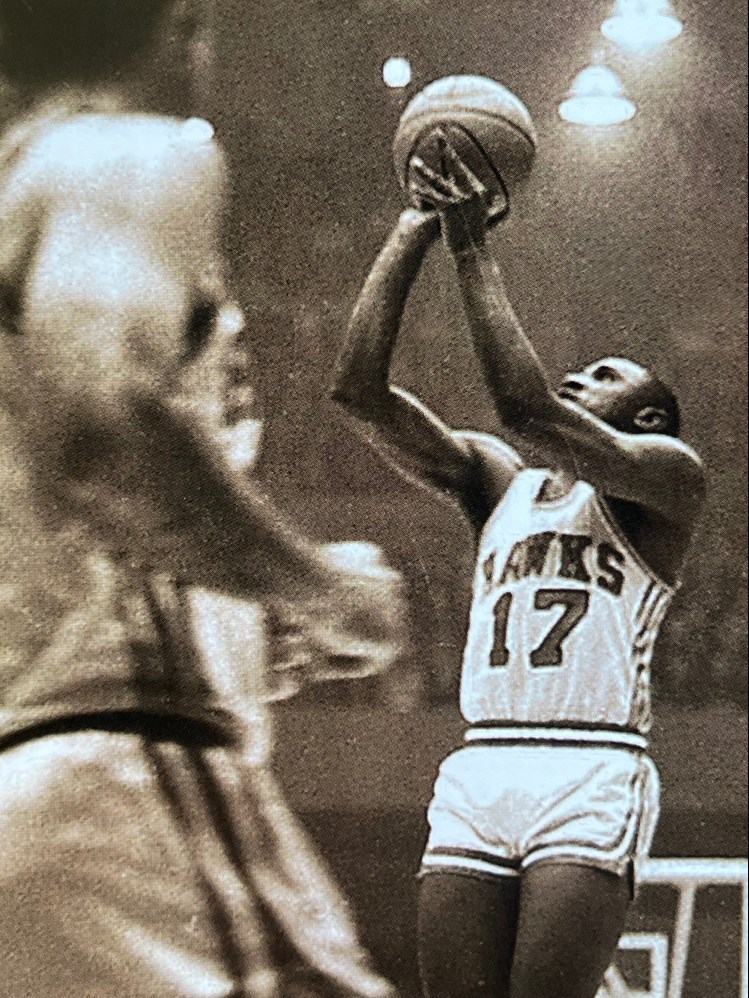

Hill made an immediate good impression on his pro coach, Paul Seymour of the St. Louis Hawks, was put into the starting lineup, and averaged almost 20 points per game for the first month of the 1961-62 season.

Monroe started a bit slowly with the Baltimore Bullets last season, but became Rookie of the Year. This season, he has made the all-star team and already is being called the most exciting player in the league, hence in the world.

Monroe’s career may be limited only by the durability of his knees, which are constantly swollen and aching from arthritis, bone chips, and calcium deposits. Hill’s career was ruined by an insidious conspiracy. He played only one season in the NBA, briefly in the defunct American Basketball League, and a few years on weekends in the minor Eastern League. He’s now teaching in Newark.

When Cleo was drafted in 1961, Coach Seymour answered the chorus of “Why him? Who’s he?” questions by saying that Hill was just what St. Louis needed: an outside shooter to loosen defenses. They were tightening around the Hawks’ Big Three forwards Bob Pettit, Clyde Lovellette, and Cliff Hagan.

The Big Three, however, resisted Seymour strategy, apparently contending that they had brought St. Louis three-straight Western Division championships without Hill and didn’t need him. Dissension smoldered during preseason exhibitions and became so hot that Seymour was fired November 17, and Hill was benched. His last night as a regular player, he scored 27 points. After a season of spot appearances, his scoring average was 5.6 points per game. The Hawks cut him the next fall, and for some reason, no other NBA team needed a guard capable of averaging 20 points a game.

Seven years later, Cleo still is remembered in the NBA, somewhat like the victim of a lynching. “Cleo Hill? He came up with the wrong team,” one veteran says.

“Do you want to know about Hill?” another asked. “This isn’t for print, is it?”

They’d much rather talk about Monroe, of course. It is pointless to compare Hill and Monroe, since they are two masters of offensive basketball and perfectly equipped with speed, grace, and spring. Each has an inimitable style, too; there may never have been a player with the combination of skills and flamboyance that distinguishes Monroe. He is a Pearl of great price. But whatever their comparative merits, Earl certainly has had an advantage of circumstances over Cleo.

Instead of trying to break into the closed shop of a championship team, Monroe started as a rookie with a young team “whose franchise was in trouble and could go with a player like him,” as a Baltimore teammate put it. No professional basketball team in Baltimore has won half its games since the 1947-48 season, and the Bullets needed the full houses that a Monroe show draws.

“It helped Earl to come with a weak team, same as it helped Rick Barry,” Alex Hannum, the Philadelphia 76ers’ coach, said last season. “With us, he’d be inhibited. I wouldn’t let him go flying around and doing some of the things he does. He probably would be playing behind (Hal) Greer and (Wally) Jones at first. He’d have to learn to play some defense.”

Instead of trying to gain acceptance by a Big Three, who were Southerners and holdovers from the days before Blacks dominated the NBA, Monroe was welcomed in Baltimore by two soul brothers—Gus Johnson and Ray Scott, the latter having come up in a Philadelphia neighborhood, too.

Scott, a 30-year-old, eight-year NBA veteran and a man whose warmth and generosity are apparent in an interview, was an especially good friend to Earl, a 23-year-old rookie. “Since Earl was a kid—since we were kids, I’ll give away my age—I’ve been watching him,” laughed Scott, beginning one of his enthusiastic preachments on the Monroe Doctrine.

“We knew that those two years he laid out of college (1962-63), he was the best player in Philadelphia. You could say we accepted him seven days after training camp began during an intrasquad game at the Civic Center. We saw he had it.

“So, last year we tried to convince him to take over. This year, we look to him. He sets our tempo. We were nothing without him. With him, we’re leading the league. Gus is our leader, and when he said Earl was in, he was in.”

Gus Johnson, also 30, has played in the NBA six years and demonstrates a classy charisma, perhaps best symbolized by the gold star carved on his large left incisor. “Got no complaints about Pearl, man,” said Gus, coming on strong. “He does the whole bit. He makes us go.”

With that sort of moral support, Earl Monroe had a license to steal center stage in the NBA. Any time down the floor, he may make a move that would embarrass an opponent to the extent of earning Earl a knuckleburger—if he were anyone but Earl Monroe. The players seem to accept him as an exotic, like Gus’s gold tooth or Earls own black silk underwear and polka-dot tie.

Once, for instance, Earl dribbled up to 6-9 Zelmo Beaty of the Hawks and kicked at him. When Beaty stepped back from the kick, Earl executed a reverse pivot that left him free for a short jump shot as Beatty watched helplessly 10 feet away. “But nobody takes that personally,” insists Hal Greer of the 76ers. “That’s just Earl’s style.”

As Hannum observed, Earl plays defense only occasionally, but his teammates, concede him the privilege, reasoning that Earl has to keep himself fresh on offense. “And remember,” recalled Eddie Donovan, the New York, Knickerbocker general manager, “Cooz (the great Bob Cousy of the Boston Celtics) never was a tiger on defense. He had Russ behind him. How much Monroe has to play defense depends on whether Baltimore’s winning. If he can get 30 and hold his man to 20, okay. But if his man gets 32 . . .

“And Monroe is just a traffic cop,” Donovan continued, meaning a player who merely waves an opponent by him. “He’ll get the forwards in foul trouble. But I haven’t seen any team isolating Monroe for a one-on-one the way they did Cazzie Russell when he came up with the Knicks.”

Monroe plays defense when it is most needed, as in the game for first place against the 76ers a few nights ago. He stole the ball from Wally Jones and made a jump shot that was the emotional highlight of Baltimore’s rally for victory in the last three minutes. Rally-sparking and game-winning plays are so regular with Monroe that it is difficult to find a Bullet victory in which he did not control the decisive moments.

Earl also, is criticized for dribbling too much. “He pounds the hell out of the ball,” a teammate said.

“Yes, but that’s what makes him so tough to guard,” said Rod Thorn of the Seattle SuperSonics.

Wally Jones agreed: “He backs into you on the dribble, and he’s got a hesitation move that makes you leave your feet, and then, when he shoots, he’s still on the floor.”

Earl even got away with criticizing NBA salaries (he reportedly makes $20,000) in comparison with those of the threatening American Basketball Association. He allegedly said he was a sucker for preferring NBA prestige to ABA dollars.

Earl’s frankness contrasts with the deference Cleo Hill wasted on the Hawks, but, “times have changed in the NBA,” claims Kevin Loughery, Monroe’s fellow guard, who entered the league during the year of Cleo’s defenestration.

“The Big Three controlled the Hawks when Cleo came up, and they didn’t want a rookie taking over,” Kevin contends. “They took it as personal. Today, they couldn’t do that. If a kid comes into the league with talent, he’ll make it quick. Just like Earl.”