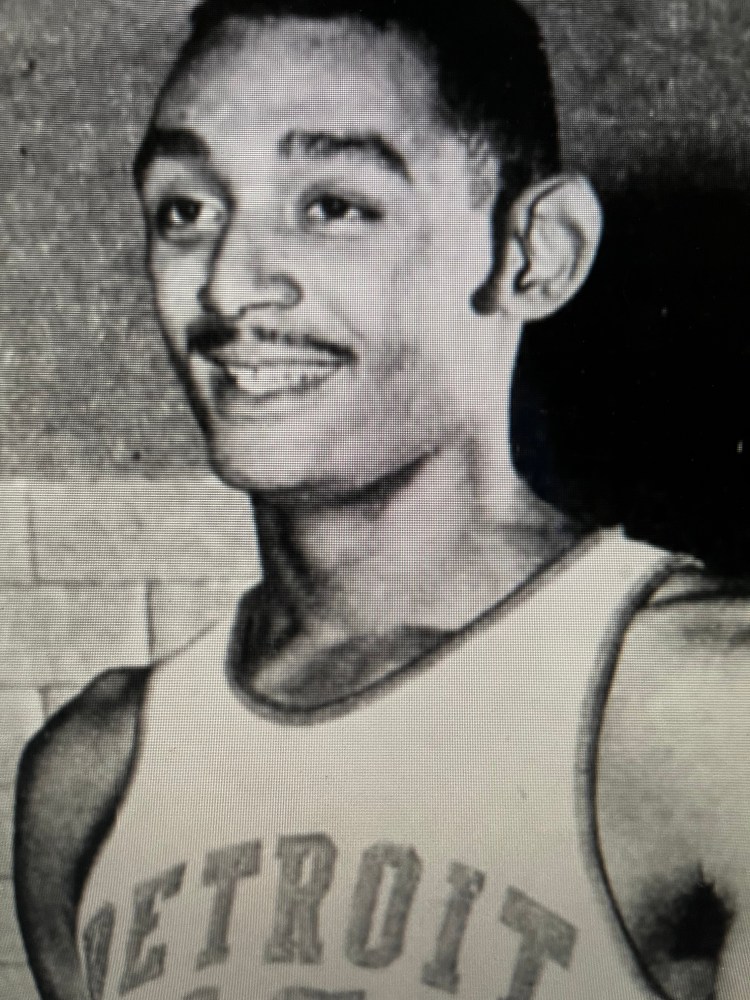

[Reggie Harding is best remembered today with a chuckle. He was the masked seven-footer who routinely held up stores in his Detroit neighborhood after his NBA career imploded and pile of cash ran low. Despite the mask, Reggie was easy to recognize at seven feet tall. “Come on, Reggie,” storekeepers are said to have exclaimed, “not again.”

Harding’s story, however, has a serious side, too. He was, if not the first, one of the first NBA players to battle addiction. The 1960s NBA had no policies in place either to punish or help players with drug problems. Into the 1980s, the NBA’s default response was to avoid the social stigma of suiting up players who couldn’t say no and have teams quietly release them. As a seven-footer with a trusty right-hand hook, Harding got a few extra chances to make good, including with the ABA’s Indiana Pacers. “He wasn’t a bad guy, and he could dominate a game,” the Pacers’ Jimmy Rayl said of Harding. “But he could be pretty scary, and I always felt lucky I lived through being his roommate.”

I stumbled onto some excellent stories about Harding. So many, in fact, that I’ll dedicate the rest of the week to Harding. Not to chuckle, although the first article from Los Angeles Times’ Jim Murray is pretty humorous (what else would you expect from Murray?), but to remember Harding and the tragedy that was his life. Murray’s syndicated column ran in January/February 1964 and offers a great intro into Harding, the troubled basketball player. After Murray, I’ve got a superb piece from the Detroit Free Press’ Joe Falls. He offers a great intro into Harding and his struggle to beat the call of the Detroit streets. But first Murray.]

****

Cobo Hall in Detroit is the most beautiful and colorful of the sports arenas in the national basketball circuit. And the team that plays in it is the drabbest. Color them gray. Even the name is about as exciting as spark plugs. The Pistons play their games in a kind of monastery quiet. You get the feeling that if you fall silent enough, you will hear the [rosary] beads rustling.

In one of the best sports towns in the country, one of the best sports nightly deposits a large egg on stage and limps off to catcalls. It’s a team that doesn’t need a coach as much as a kind word. They are as anonymous as egg candlers.

The Lakers came to town, and they left 30 points behind them in Los Angeles—in a splint on the hand of Jerry West, all-pro guard and the team’s high scorer. The Laker lineup is dotted with the names of guys who never got on the score sheet unless the team is 20 points ahead or 20 points behind and the clock showing two minutes to play.

The Pistons have their adversaries in perfect execution position. But they are so clumsy, any governor in the world would issue a pardon on the basis of double Jeopardy. The Pistons get a 12-point lead and then suddenly get so rattled, the ball is up with the ushers more than the backcourt.

But the Lakers are counterfeit, too. They were like a man whose leg is so newly broken, he has not learned to move on crutches yet. Until West gets back, the Lakers are on crutches. They are playing poker on short money. They can’t afford any mistakes. They haven’t got the cards. So they have to know when to gamble.

The Pistons do not figure to be too tough to do this, too. They are a team that draws to an inside straight all the time. They are like a guy who can never remember what cards have been played. You should have to have a license to play them. But suddenly on this night, an ace suddenly falls out of the Pistons’ sleeves. This is a seven-foot face card who answers to the name “Reginald Hereziah Harding,” and it has been called out by a few judges in his time, which is only 21 years.

Reginald Hereziah was as illegal in the National Basketball Association two years ago as holding a center’s belt on the jump. He was a high school dropout who needed a car in the worst way one night; so he took one in the worst way.

The ink had barely dried on this beef before Reginald was on a spate of cherry picking in northern Michigan with another migrant agricultural workers. They had words which led to deeds—in this case, an alley fight.

Since Reginald is seven foot, give or take an inch or so, and only slightly lighter than a B-29, the other fellow chose to call it less a fight than an atrocity. If Russia attacks Albania, you don’t wait to find out whose fault it was.

He later consolidated his reputation by pulling out what appeared to be a weapon in a café. Reggie said it wasn’t real, but nobody stopped to find out.

Reginald appeared to have as much chance to play in the NBA as Khrushchev. As desperately as they might want him, they had no hankering to transfer their home games to jail. Even when his class graduated, which made him technically eligible for the draft, Reggie Harding was considered as a remote possibility for the NBA as President Harding.

He signed on for a leaky-bus career with a team of clowns who had a few routines left over from their days with the Harlem Globetrotters. The “Harlem Road Kings” were picking up the leavings on the Laurel and Hardy basketball circuit.

Reginald began to wish he hadn’t hit that cherry-picker in the nose when he got a load of the travel conditions. He went through towns that not only he didn’t know existed, neither did Rand-McNally. He slept in beds a dog would slink away from. And those were the good nights.

Reginald began placing long-distance calls to owner Fred Zollner and publicist Fran Smith of the Pistons—collect. The Harlem Road Kings were not picking up any phone tabs. The Pistons were. This was a team that would accept collect calls from the Count of Monte Cristo, so desperate were they for the sound of a voice.

As they lost more and more games, Reggie Harding’s record was beginning to look more and more like cookie stealing. This was a team so desperate they would play their starting five in mask and false whiskers if it would help any. Sonny Liston became heavyweight champion of the world on a record that made Reggie Harding look as if he done nothing more serious than try to hand in a late streetcar transfer.

The Pistons appealed to the league. The league consulted the record and decided they either had to give the Pistons permission to play Harding or to play in the dark. They spent $65 in toll calls tracking him down, some to places they could have reached quicker by pigeon.

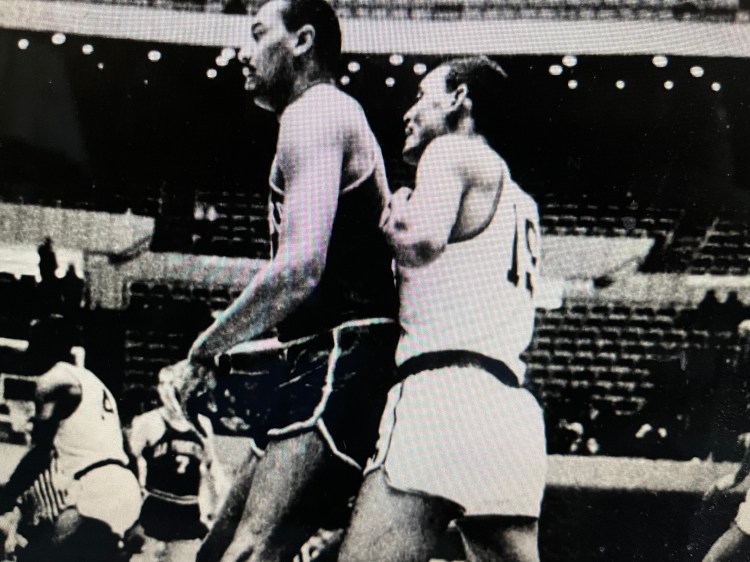

Reggie rushed to Detroit. One of his first games was against Will Chamberlain. Wilt did everything but fold him up and stuff him through the basket. He never even raised his voice. As each game came, he got better.

He was at his best against the Lakers, even granting they are flying on one wing. ”He will be one of the great ones,” predicted Fred Schaus, who now has one more seven-foot problem to conjure with in a league he had just begun to solve.

But best of all, Detroit finally has someone recognizable in the skyline in the middle of the court. And maybe just in time.

[Now to Joe Falls and a lot fewer similes. (Thankfully for those who tire of Murray and his like a . . .) Falls’ story appeared in the Detroit Free Press on December 19, 1965. Or less than two years after Murray’s similes.]

DETROIT—This is over on Broadway Ave., next to a parking lot at the foot of Gratiot, and the white lettering on the sign over the door says: “Broadway Clothes.” Another sign in the window says: “Tuxedo Rentals, WO-1-2669.”

It doesn’t look much like a rehabilitation center, but this is where Richard Jarrett, one of the store owners, is trying to put together the pieces of the seven-foot puzzle that is Reggie Harding.

“When he first came here, he was impossible,” said Jarrett. “He’d show up late, he’d leave early, he’d spend hours on the phone. The other merchants told me I was crazy to hire him. But I’ve known Reggie a long time, and I know he needs help.”

HARDING, REGGIE . . . SPORTS. There are 30 clippings on him in the Detroit Free Press library. Six are about his basketball ability. The other 24 are about his off-the-court activities.

Or rather, his in-the-court activities.

These include such heady headlines as: Reg Guilty of Assault . . . Harding Granted New Trial . . . Reggie Harding Arrested in Break-in . . . Harding Put on Probation . . . Judge Dismisses Charges on Reggie . . . Reggie Arrested for Reckless Driving . . . Harding Accused as ‘Gunslinger’ . . . All-City Cager Held in Theft . . . Pistons Won’t Take Reggie Back . . .

The tribulations—and trials—of Reggie Harding aren’t new. He has been in the soup ever since he became a teenager. The Detroit Pistons tried to straighten him out. They fined him no fewer than three times for his behavior, and Reggie still stands as the only player in the history of the National Basketball Association to get a $533.23 tariff slapped against him.

He used to be a big man, The Reg. He used to pull down “15 thou” from the Pistons and drive around town in his 1964 Thunderbird and watch them fenders, boys, I don’t want this baby scratched up none.

Today, he’s the world’s tallest Detroit bus rider. The Thunderbird is gone, along with about everything else. But, now he’ll phone Mr. Jarrett if he’s going to be late for work, and he stays around until quitting time at 7 p.m. He has even made some sales, and in a good week, he’ll make up to $125 [about $12,000 in today’s money].

Jarrett started something new for Reggie Harding last week. It’s called a bank account. Every Friday, whether Reggie likes it or not, he takes $12 out of his paycheck and puts it in the bank. “It’s not much,” said Jarrett, “but it’s a beginning.”

As we spoke in the back room of the store, Harding, dressed in an olive suit and an open collar shirt, kept shifting from one leg to the other and looking off into space. He plugged the pop machine twice while I was there.

Jarrett didn’t hold back anything, because the time of hurting Reggie Harding’s feelings is past. “I know Reggie has been in plenty of trouble, and I know he has said he’s sorry over and over again,” said Jarrett. “But now, I think Reggie is beginning to see the light, because now he knows what it is to be poor. Let’s face it—this will straighten him out more than anything else. When he quit playing basketball, he found out that he could count his friends on one finger.”

Harding still retains some of his arrogance, but it’s not offensive. Sure, he said, he misses playing basketball. “It’s part of me,” he said. But he added: “I’ve still got the ability, and they can’t take that away from me.”

He still believes he has been a victim of circumstances, that too much has been made of his extracurricular activities. “One conviction,” he said. “That’s all—one conviction. And then the judge suspended the sentence. What kind of conviction is that?

“When I played for the Pistons, I did the job for them on the floor. Get that—on the floor. My leisure time was my own. They didn’t raise me, they didn’t put me to bed at night, they didn’t own me.

“And what did I do to the NBA? Did I bet on the games or something?”

Harding has been released by the Pistons and is under suspension by the NBA. He wrote to Walter Kennedy, the commissioner of the league, asking what steps he should take for reinstatement, and, Reggie said, “He wrote back to me saying he needed more information—like a police record, if any.”

Harding made a face.

“If any . . .” he said.

Jarrett broke in: “Let me say this for Reggie. He’s really trying to do a job in the store. He swabs the floors and washes the windows just like the rest of us. Last weekend, I was really proud of the way he worked with the customers. He was a real champion.”

At Jarrett’s suggestion, Harding will spend one night a week as a “Big Brother” out of the 10th police precinct, taking some underprivileged boy out for the evening. “Reggie got in with the wrong crowd,” Jarrett was saying when the phone in the back room rang.

Harding picked it up” “Broadway Clothes.”

He listened for a moment, then said: “Well, I’d suggest to bring it back, sir, and we’ll fix it. I think it’s better to show me what’s wrong instead of telling me.”

He also said another thing. He said “thank you” when he hung up the phone.