[In January 1969, two Baltimore reporters got “locked up” in an airport waiting more than six hours to board their connecting flight to cover the NBA Bullets. To fight the boredom, the two embarked upon selecting their unconventional assortment of all-time NBA teams: All-Crybaby, All-Bald, All-Schoolyard, All-Hatchet, and All-Ugly (“the entire Seattle team”).

Reggie Harding, who last played in the NBA in 1968, lived on in league lore as a member of their All-Mustache and All-Flake teams. Harding’s credentials for the latter took a giant leap forward in October 1969 when a Wayne County judge sentenced Harding to 2 ½ years in the state penitentiary for violating his four-year probation on an earlier burglary charge. Harding, age 27, had violated his probation by getting caught helping to boost a 14-year-old boy through an apartment window to burglarize the premises. It seems that Harding needed to steal to support his $100-per-day heroin habit, which had been going strong for about three years and very much coincided with his pro career.

Said a local radio personality, “I’ve seen [Harding] many times in a house on Fisher, shooting dope, and out on the porch, as tall as he is, bent over—the nods, they call them—scratching and nodding. And, of course, he’s very noticeable. And the police, they’ll go right by the porch and see all this, and nothing happens until there is some kind of furious activity around what he’s doing. It’s a very weird thing.”

After his sentencing, Harding tried to look on the bright side of his very weird thing. “I know The Man gave me a lot of brakes—and I blew it,” he said. “But I still don’t feel this is the end of the line.” What about his drug habit? “It’s like the cigarettes you smoke. It’s a matter of strength and weakness.”

By the end of the year, Harding had begun serving his sentence at Southern Michigan State Prison (a.k.a. “Jackson Prison”). A few months later, the Detroit Free Press’ George Cantor paid a visit to the prison’s tallest inmate. Before driving to Jackson the warden told Cantor, “Maybe I should tell you this before you see [Harding]. His attitude really isn’t all that good. He’s a big shot here and well . . . you know what happens. It’s about what I thought would happen by his reputation. He’s doing himself no good if he wants to get out of this place early.”

With that, here is Cantor’s account of his trip to Jackson Prison, which ran on March 29, 1970 in the Detroit Free Press’ Sunday Magazine.]

****

Thick fog was clinging to the road all the way to Jackson. Several cars nearly missed the Cooper Street exit off the freeway, trailing a misty tangle of red brake lights across both lanes. Even the turrets and watchtowers of Southern Michigan State Prison had disappeared in the murk and a cold rain pounding against the walls.

Reggie Harding watched the fog from the inside with a flicker of interest. “I kept saying to myself: ‘Man, all you have to do is walk out that door into the fog, and they’ll never find you.’

“I’m a trusty now, so I’ve got a little more freedom, like the door staying open all day. But no-where, no-how do I walk out that door. I make that move, and it’s five more years for the Big Man, and I come up for parole in September.”

The Big Man—Harding’s own name for himself—was trying to find a comfortable position on the absurdly tiny chair in the prison visitors’ room. It was impossible. The legs that vaulted his frame to its seven-foot height were sprawled out along the floor like an entirely unrelated body, and passers-by had to be alert to avoid tripping over them.

“Sorry about not shaving,” said Harding, rubbing a hand over the stubble on his chin. “I wasn’t expecting any company today. I was just lying around reading a magazine. My new job assignment hasn’t come in yet, so I got nothing to do. It’s tough trying to get through the day.”

Before Harding entered Jackson, he said he’d like to learn a useful trade there—like meat cutting. “Naw, I gave that up because it might be detrimental to my hands,” he said. “A lot of guys slice their thumbs and fingers off while they’re learning. I don’t need any of that.”

He is 27 now, and it’s been nine winters since he led Detroit’s Eastern High to the last of its three-straight city titles. He has been off heroin for more than a year. His body is back to its 240-pound playing weight.

They asked him once: “Reggie, do you think you’ll be able to hack it in the National Basketball Association?”

Reggie looked at them with the mocking laughter in his eyes: “Is the sun gonna shine?”

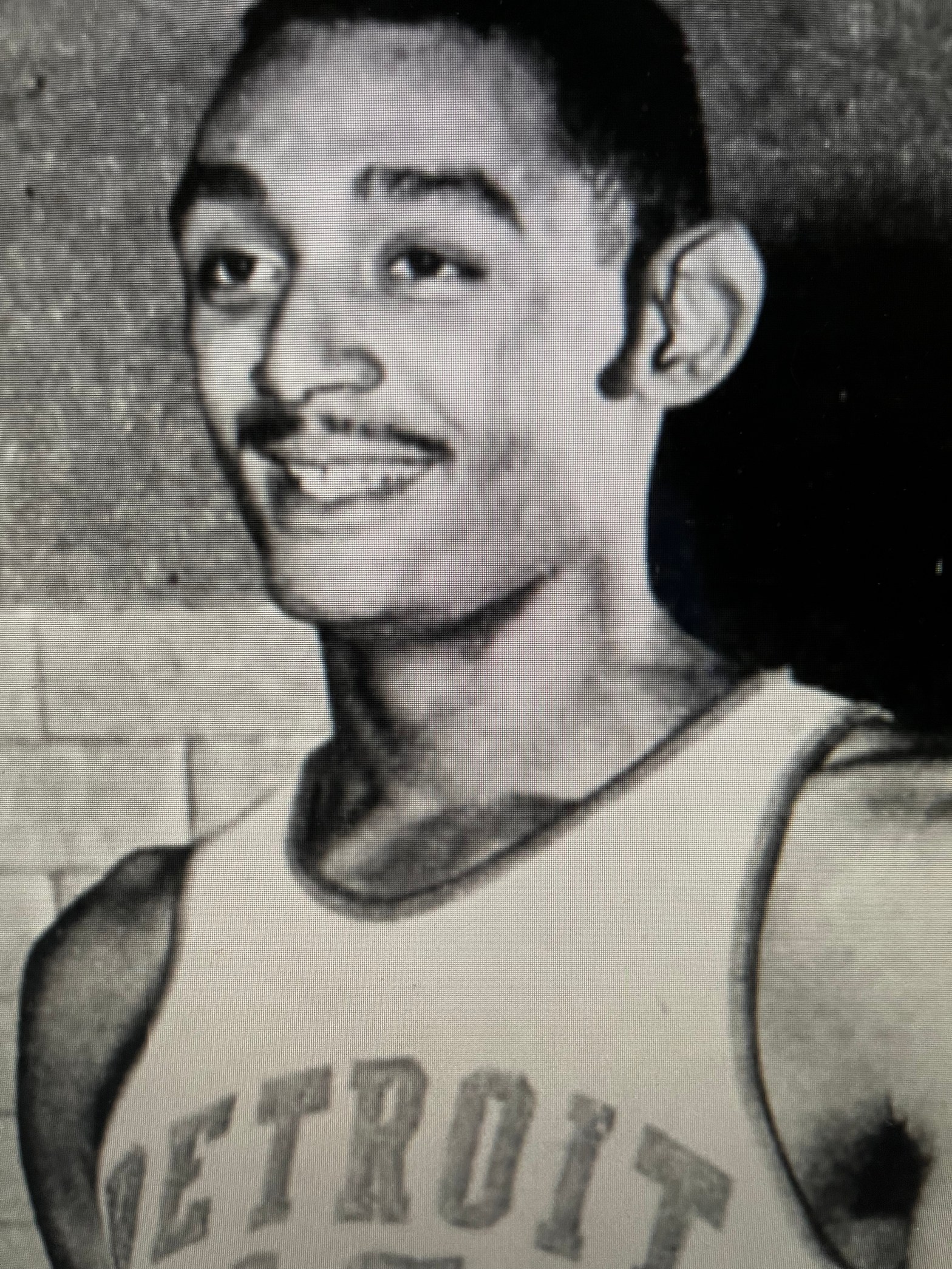

The Detroit Pistons signed him eagerly in 1964 and installed him at center midway through the season. He played against the best big men in the world and averaged 11 points—good for a rookie—and 11 rebounds a game—good by any standard.

The team had a chance to draft Willis Reed after that season, but Harding looked like gold for the next 10 years. Eighteen months later, he was suspended by the league. There was a conviction on assault and battery on a cop. He was picked up in a blind pig [booze joint] while trying to hide behind the sofa.

Traded to Chicago in 1967, he was arrested for armed robbery, arrested again on a concealed weapons charge, and outran police who were holding him for narcotics withdrawal. He was finally sentenced to 2 ½ years in Jackson last October for probation violations.

He was a pathetic figure then. His feet bolted out of the shoes six sizes too small. His massive body was wasted by the heroin that he had pumped into it for three years. But now, somehow, he pulled it back together. And the old (“Is the sun gonna shine?”) mocking laugh was back in his eyes.

“Getting out, man, that’s all I think about. I still got basketball. I played on the prison team, and we won the tournament last year. My average? I don’t know. I wasn’t concentrating on that. It was something to do with the time. Now I just get to play intramural ball because I’m a trustee. That’s no challenge at all.

“But basketball . . . this is my gift, man, the talent I was born with. And if the Pistons are willing to give me a chance, I’ll play for them. If you got the bread to pay me, I’ll play for you.

“Let’s face facts. I’m a better center right now than anyone the Pistons have, but I’ve got something to offer them. I’m what you might call a gate attraction.

“Your paper sent you here to do a story on me. They haven’t forgotten the Big Man. People know I’m here. I’m from Detroit, and I liked it there. Given the proper adjustments and the proper chance, I know I can make it back with them.”

How many chances does one man get? Harding has sung the same song before, dozens of times. After the arrest for auto theft at Eastern. After the suspension from the NBA. After the conviction for assault.

This was the time he’d learned his lesson. He’d keep his nose clean now and concentrate just on basketball. “Give me the chance, man, and I’ll make it.”

Harding was waiting for the question when it came and started answering before the interviewer had it properly phrased.

“This time it’s different,” he said. “This place here . . . man, it does something to you. This is no place for no man. I never knew what the consequences were before. I’m man enough to realize the mistakes I’ve made. I can’t undo what’s been done. I’m paying the price for it, you understand?”

“This is 2 ½ years I can never get back, you understand? Years I can’t spend with my family. It would wake any sensible man up. I owe myself a chance, not so much for myself as my family and friends. This is a setback I’m having now . . . a setback. I’m not the type of man who gives up.”

The Big Man moved his bulk to a new position in the seat, and inmates and their visitors sitting nearby turned slightly to catch a look at him. He was something. Reggie Harding. When he was 12 years old, he was already 6-2, and in the alleys and rec centers where basketball players are made, he was doing it to the high school kids.

He had co-ordination along with the height, and there was never a doubt (“Is the sun gonna shine?”) that he’d make it big. In high school, they said he was ready for college ball and maybe even the pros.

A Black inmate passed the table and gave Reggie a hand-slap. “Hey, brother,” mumbled Harding, and all the heads turned again. The Big Man watched them look around out of the corner of his eyes. He decided to lay it on him a little. A mini-skirted woman visitor walked by, and he stretched out to full length and moaned.

“Been too long,” he rasped. “I can’t take that at all.”

Harding complained: “Everyone judges me by the past. But really, what did I do? The only person I ever hurt was Reggie Harding and my family. Somebody like [Detroit Tiger ace] Denny McLain gets in trouble, and they’re taking up collections to help him meet his house payments. Nobody once said, ’Hey, Reggie’s in trouble. Maybe we can help him out.’ I had a family, too, but no one seemed to think about that.

“What McLain did hurt all of baseball. I never hurt the NBA. The big thing on me was my narcotics habit. But I was never convicted for it. Any information that came out about it was offered by me.

“Now I’m anxious to see what happens in this case, how your so-called justice will operate. Do I get the chance he’ll get? I’ve seen a lot of things in the time I’ve been here,” he said. “I have a broader outlook, a respect for life. This is a new guy you’re seeing, a resurrection. I’m back in school now, and I’m ready to graduate any day.”

Harding realizes there may be some problems about catching on with the Pistons when he gets out of Jackson. “Maybe a new chance would work out,” said the team’s general manager Ed Coil. “Maybe we should give it to him.

“But there’s still the matter of rights to his contract. As far as I know, the Chicago team still holds title to him. They were the last club he played with.”

If that part falls through, Harding still has definite plans for his life. He’d like to help drug addicts. “I have a deep concern for helping my own kind,” he said. “I’ve gained deep knowledge of me, and I can help the other brothers.

“Everybody talks about dope fiends and addicts. Now it’s all over the papers. But they’re treating it all wrong. Like with me, it started with the group I ran around with. You identify with your own kind, and your environment entices the things you may do.

“We’d start off, taking a drink before going to a party to feel good. Then it was a reefer. Then dope. And you start thinking to yourself that this is nice. It covers things up for a minute.

“You get depressed, you start feeling down, and you depend on it. But it’s not just happening in the ghetto. Check it out in [wealthy] Grosse Pointe and Bloomfield Hills. People up there killing themselves, jumping out windows every day. And they’re supposed to have everything.

“They give you pills and rest for your habit. But they never treat your mind, the root of the thing. There’s a reason for everything. There’s got to be a reason why a man does this to himself when he knows what will happen,” Harding said, talking rapidly now.

“I was covering something up. I know what that was now. I should have got myself together like a man. But it was easier to forget. You give a man his pills and his rest and send him right back out into the same jungle. Most of them have nowhere to stay alive. They spend so much money on missiles and prisons. Turn this place into a hospital, man. Treat the causes. Try to help ‘em all.”

He was something, Reggie Harding. Knew how to wear clothes. Drove the sleek Thunderbird. Always lots of friends around.

The same year Harding made high school All-American, a forward on the honor team was Bill Bradley of Crystal City, Missouri, a posh suburb of St. Louis. Here is the American experience underlined in red pencil.

While Harding tried to make it into a college with his Eastern High background, Bradley breezed into Princeton. While Harding wound up with outfits like the Harlem Road Kings, Bradley was named College Player of the Year and led his Ivy League school into the semifinals of the NCAA tournament.

Harding was arrested for a concealed weapons charge at about the same time that Bradley became a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford. When the soft-spoken, scholarly Bradley joined the New York Knicks, Harding was feeding his $100-a-day habit by means of armed robbery. As his avocation now, Bradley concerns himself with penology, the study of prisons. His interests finally coincide with Harding’s there.

The comparison Is probably unfair to Bradley, who simply made the most of opportunities given to him by birth and skill. But aside from the fame that their athletic talents brought them, was there any difference really between their lives and a few thousand or so anonymous counterparts?

“I realize now that you can’t hang out forever,” Harding said. “I hung out too long. I wanted to stay with my old friends, and finally I got myself trapped. When you change your life, you’ve got to change all the way around. But when I played basketball, I just couldn’t identify with other people. In my mind, all they were saying to me was: ‘You’re nothing but a ghetto kid who never went to college.’

“But life ain’t about college. I could turn people around with what I know—and I don’t mean slang and that rap. I mean real knowledge. I can take the best scholars in the world and turn ‘em around.

“All I ever did, man, was what a whole lot of people would like to have done themselves if they only could.”

It was time to go, and Harding walked his visitor to the door.

“Hey, do me a favor,” he called. “Tell Ed Coil that the Big Man is on his way. (“Is the sun gonna shine, man, is the sun gonna shine?”) Tell him I need the money, and he does, too. Tell him that for me.”

The guard took the visiting slip and pressed the button that opened the gate to the outside. Beyond the doors, the fog had grown even thicker. The man on the radio driving home said that many people had lost their way.