[In June 1971, after his release from Jackson Prison, Harding returned home to his hardscrabble Detroit neighborhood and its familiar influences, good and bad, and investigated another shot at the NBA. “Stop the world,” Detroit sports columnist Joe Falls wrote sarcastically, “Reggie Harding wants to get on.”

“Have you changed?” Falls asked “The Bad Boy of Basketball.”

“I never did two years [in prison] before,” Harding answered.

“Can you still play?”

Harding shot back: “You find the place, you bring in the guys, and I’ll be there. I know it’s still there. All I did in prison was stay in shape. I can dunk. I can drive. I’ve got a left—all of it. But I know I’ve got to prove it.”

Before Harding, now age 30, got to prove anything, he took two hard slaps and two bullets to the head. The Bad Boy of Basketball died the next day. The murder shocked Detroit and left many searching for adequate words and theories to make sense of this homegrown tragedy. Harding, love him or jeer him, should have been snatching rebounds in the NBA with the best of them. But Harding wasn’t prepared mentally to navigate the off-court twists and frequent turns of his brief rise to near-NBA stardom.

This article, which ran in the Detroit Free Press Sunday Magazine on November 12, 1972, captures Detroit’s search for answers to Harding’s murder. Reporter Tom Ricke, who would later battle his own mental health issues and who recently passed away, takes a compassionate—and long—look at Harding’s troubled life. He captures Harding’s challenges of growing up poor, athletic, and seven-feet tall in the 1960s.]

****

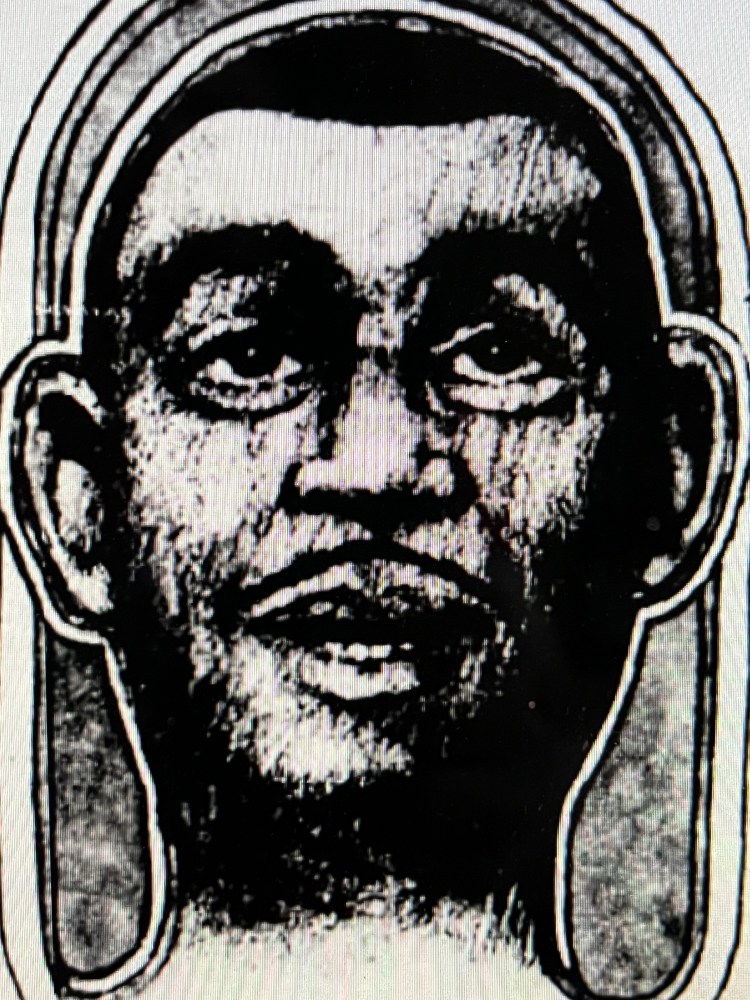

It was late in the afternoon of Friday, Sept, 1, and Reggie Harding was hanging out on a corner of Kercheval trying to get his life back. At one time, the towering seven-foot man who loomed over the people he was talking to averaged 12 points a game and pulled down nearly 1,000 rebounds a season for the Detroit Pistons. He was rated the fifth center in the league during the 1964-65 season, his first full year in the NBA. He was the only player in the history of the league to sign right out of high school. [Ed. note: Not quite correct]

But Reggie was suspended for the 1965-66 season for his many brushes with the law, and he became a junkie. He played two seasons for the Pistons after that, but he was never the same.

On this afternoon of Sept. 1, 1972, Reggie Harding’s fame and chance for fortune were in the distant past. Reggie was spending most of these days on the street corner, drinking from a bottle hidden in a brown-paper bag and talking with the guys about dope and women and pool.

He had nearly lost his life to heroin, but now he was trying to get it back. He was no longer a junkie. He had been taking methadone religiously for two months. The following Monday, he was to start a job in a factory, the first job he had since serving his two-year term in Jackson Prison for violation of probation. He had been convicted of armed robbery.

Harding was even going to church twice a week. He told his friends that he was trying to get all the help and strength he could from every place he could, because he needed it.

Bill Ervin, the man who first taught Reggie about basketball, was getting up at 6 a.m. every day to run with Reggie and throw the ball around. Reggie was riding a bicycle around to help him get in shape.

****

People couldn’t believe the “Big Fellah” was getting in shape. But that Friday morning, he’d spent hours trying to get some friends together to play basketball. He told his friends that he was going to show the big shots downtown, the ones who kept saying he was a loser, that a 30-year-old man could make a comeback.

But Harding admitted to his closest friends that he really doubted whether he could make it again in basketball. He was going to give it a good try, he said, but all he really wanted to prove was that he could have a home and family and a job like anyone else.

For the last month, Reggie had been seeing a lot of 26-year-old Carl Scott, one of the many young men who gathered on the streets of the near East Side. Reggie had always known Scott, but not well. Reggie was the kind of person who would use the last five dollars he had in the world to buy a round of drinks for his good friends. In the past month, Scott has become one of those friends.

Scott had served two short terms in Jackson Prison on two different assault charges. At the time, he and Reggie started to hang around together, Scott had been out of Jackson for about four months.

Reggie had talked Scott into going to church with him the week before and was also trying to talk the younger man into going to the methadone clinic with him. Scott and Reggie and a group of other friends were standing and talking to a girl named “Motorcycle” that afternoon. Witnesses later told police that, all of a sudden, Scott slapped Reggie in the face.

Reggie was not a violent or mean person. He rarely hit others, except when he was clowning around. If someone would threaten him, Reggie’s favorite trick was to pick up the man, hold him over his head, and then drop him and say, “Don’t mess with the Big Fellah.”

“Are you for real?” Reggie said to Scott after being slapped.

“Yeah, I’m for real,” Scott yelled back and slapped Reggie again.

Reggie slapped Scott back, then held the much smaller man and embarrassed him in front of the others by telling him, “the Big Fellah” didn’t want to hurt him in a fight.

Scott ran away as soon as Reggie let him go, and Reggie was so upset that he sat down on some porch steps nearby and cried. Reggie asked his friends if he had done the right thing, and they assured him he had. They told him that Scott must have been crazy to hit him for no apparent reason.

Reggie started to walk to a friend’s house. He stopped at Parkview and Kercheval to talk to a couple of girls. A car stopped around the corner. According to police reports, Scott got out with a pistol and walked up to Reggie, who looked down at the gun. He didn’t think for a minute. Scott would really shoot him. They were good friends. He had done nothing to cause Scott’s irrational behavior. “If you shoot me,” Reggie said with a mocking smile, “shoot me in the head. I don’t want to feel no pain.”

Scott pointed the gun at Reggie’s head and, according to the police report, pulled the trigger. Reggie, looked down in disbelief. “Why? Why? Man, you shot me,” Reggie said as the world was spinning around him.

Scott fired another shot into the big man’s head and ran to a car, which was waiting to take him away. A first-degree murder charge was issued later on Scott, but by mid-October, he had not been arrested. [Scott was hiding out in Cleveland, but would be arrested in April 1973.]

The sun burned down on the littered sidewalk as Reggie Harding lay there dying. Reggie grew up near there and could have been a superstar on the pro basketball court, but he could never leave. Now he was dying there. At one time, Reggie thought he would make it out of the streets. At one time, he was so confident. When a reporter asked the high school All-American center if he could make it in the pros the next year, Reggie had said, with that mocking smile of his, “Is the sun gonna shine?”

****

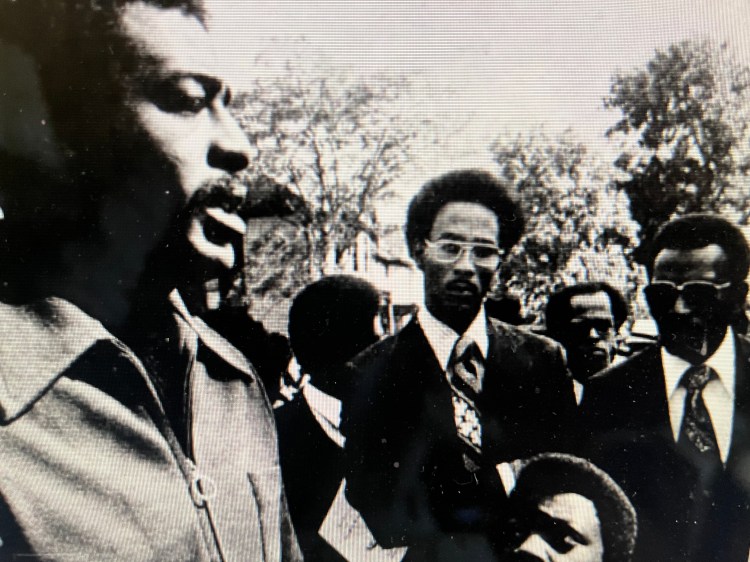

Reggie died in Detroit General Hospital the next day. His funeral was one week later on Saturday, Sept. 9, at the Greater Mount Carmel Baptist Church just down the street from the burned-out shell of the old Eastern High School building, where Reggie became a star.

Hundreds of people stood outside the church in the hot early autumn sun, waiting for them to bring Reggie’s body into the church. A couple of writers talked about that mocking sun and how they knew it would be shining brightly at the funeral. (Is the sun gonna shine?)

Alvin (Blue) Lewis, Dave Bing, Judge Edward Bell, and Billy Rodgers from the Pistons stood on one side of the lawn. The relatives from both of Reggie’s families stood in the center. Reggie was adopted when he was a baby. He was raised by foster parents and, later in his life, he found out who his real mother was and became close to her and her family.

Reggie’s street friends stood on the other side of the lawn. A few were dressed in stylish, expensive clothes with their customized Cadillacs and Lincolns parked nearby. But most of them looked as if they had pressed their only suits to come to the funeral.

Reggie’s real mother, Mrs. Lillie Mae Thomas, died two weeks before he did. She was shot to death in an argument with her husband. At her funeral, Reggie stood for 15 minutes over her coffin and told the funeral director how he wanted his own funeral. People thought he was drunk or something, but now two weeks later at Reggie’s funeral, the people were saying he knew he was going to die.

The flowers on the altar, were just what Reggie wanted. He asked for two special floral arrangements: a basketball backboard and a Cadillac. There they were on the altar, the symbols of the two lives that Reggie Harding tried to live, the two lives that pulled him apart and left him with nothing.

The backboard made of red and yellow roses represented all that Reggie wanted to be and never quite became on the basketball court. The Cadillac was the car that Reggie had always wanted, but never had. But that arrangement of black and white flowers was more significant than just an expensive car. It was a sign of success on the streets, of a man who had made it. When Reggie was a young boy, the numbers men and pimps drove them. Later the dope dealers.

The dope dealers killed Reggie. He hung around with them after he was suspended from the Pistons. They gave him free heroin. Once his habit got too expensive for them, they dropped him. So Reggie made a career out of robbing dope houses at gunpoint to support his habit. Although police and relatives theorize that Carl Scott (who made it a point to get so close to Reggie a month before he killed him) was paid by someone to do it. But the dope dealers had already killed Reggie years before Scott pulled the trigger.

Billy Rodgers, the Pistons sales and promotion manager, spoke at the funeral: “What was so unique about Reggie,” he said, “is that he wasn’t just seven-feet tall. He had a great, great gift of playing the game. He was quick and graceful and coordinated. He was the only one to be signed out of high school.

“I don’t believe now that it’s all over,” Rodgers said, “that we can all say we gave him a fair chance. We owe him. Reggie Harding is dead. We’ve lost a great, great man.”

Hundreds of people at the funeral sang, “The Last Mile of the Way,” and marched up to the elegant nine-foot-long casket. They cried over the big man’s last fixed smile between those two floral arrangements and whispered about how relaxed and happy he looked. The procession to the cemetery was about a mile long.

When they arrived at the cemetery, they found out the cement vault was too small for the nine-foot casket. Reggie’s wife became hysterical when the funeral director told her to leave, and he would take care of it. She insisted that her husband’s body be taken back to the funeral home.

“The Big Fellah,” friends and relatives whispered over and over again, “the Big Fellah isn’t ready to leave us yet.”

****

It was about 20 years ago when the exceptionally tall 10-year-old boy named Reggie Harding used to cut through Bill Ervin’s yard several times a day. The boy lived at 4669 Harding, and every time he cut through the alley and Ervin’s backyard, he would knock on Ervin’s window and smile.

“I was on the porch one day,” Ervin recalled, “and he came up and said, ‘I’m Reginald. I live behind you.’”

Soon, Reggie Harding would come over and sit on Ervin’s front steps and talk to him. He told Ervin that he wanted more than anything to be a basketball player. That, he hoped, would be his way out of the neighborhood, his way to money and prestige.

But young Reginald was shy. Although he was the favorite of adults in the neighborhood, he shied away from the other boys who played basketball at the school yard. One day Ervin, who was then 20 years old, took Reggie there and introduced him to all the young players.

From the first moment he touched a basketball, Reggie Harding knew how to handle it. After he began to develop his skills in neighborhood games, he got his own ball and took it with him wherever he went. He even slept with it. He was quite a sight, walking around in his huge tennis shoes with a ball bouncing in front of him. When he sat down to talk to someone, Reggie held the ball in his right hand and sucked the thumb of his left hand.

Reggie never grew out of the habit of sucking his thumb. He did it all of his life whenever he was thinking about something or relaxing. Some of his friends called him, “Baby Huey,” and he hated that nickname. People who knew him well laughed about it. They didn’t know what else to do when they saw the seven-foot, tough, masculine, full-grown man sitting in a chair that always looked too small and showing his insecurity by sucking his thumb.

Reggie grew taller and taller, and by junior high school, he stood over 6-5. Neighborhood basketball games weren’t fun anymore. Whatever team Reggie was on automatically won. By the time he got to Eastern High School, Reggie was 6-10. Bill Ervin took a special interest in the young man. He ran and worked out with him, and he kept telling Reggie that he could be anything he wanted to be.

Soon it all began to come true. Reggie led Eastern High School to three-straight city championships. He was chosen the best high school center in the nation by several sports magazines. His popularity grew as fast as he did. Wherever he went, people would stop him and say, “Hey, man, are you Reggie Harding?”

He was the king of the basketball court, the king of the school, and the king of the streets of the lower East Side. But every once in a while, he would stop by and see Bill Ervin and ask, “Do you really think I can be a pro?” His fatherly neighbor would say, “Reggie, you can be whatever you want to be.”

It was during the years when he was a high school basketball star that he met his future wife, Nadine. Her brother told her about Reggie, “that huge dude that plays basketball.” He told her that he hung out at the ice-skating rink. So, one night in February of 1958, Nadine went skating to a get a look at Reggie. “A lot of kids went down there just to look at him,” she recalled, “and just to get a close look at him.

“Well, I was skating with my brother and Reggie came by and looked at me, and I was playing hard to get. I’ll never forget his first words, ‘Look what the angels blew in tonight.’ I just kind of turned my head and skated away.

“He came back and heard my brother asking me why I turned away after I came down especially to meet him. Reggie acted mad and said he knew I wanted to meet him and asked me if I would skate with him. I said I would be happy to.”

Reggie started to make headlines in Detroit papers when he was in high school. There were a few stories about his basketball ability, but most of them were about the trouble he got into. His foster parents were worried that he was hanging around with the wrong crowd, so they arranged for him to spend the summer up near the town of Cadillac picking cherries.

Reggie was the only Black youth on the farm, and he hated it. He told his friends how the others made fun of his size and color. He asked the farmer for his money. Reggie said he wanted to go back to Detroit. The farmer refused, so one night Reggie stole his pickup truck and drove it to the nearest town.

He gave himself up the next day. The papers wrote stories about the high school center getting arrested, but no one bothered to ask just what he was doing picking cherries? Or why he stole the truck?

The next year, Reggie was arrested while participating in a school track meet on Belle Isle. A 15-year-old girl claimed she had intercourse with him. He was charged with statutory rape. Again, the papers ran stories about the arrest, but when the charges were dropped, there were no stories. Years later, when Harding got into a lot more trouble, the newspapers dropped “statutory” from rape and simply said he had been arrested for rape in high school.

****

Reggie’s real mother was 17 years old when she had him. She wanted to keep her baby, but she was not married at the time, and her family forced her to give him up for adoption. Hezekiah and Fannie Harding lived in the neighborhood and knew Reggie’s mother. All of their lives they made their house a home for unwanted children. They decided to adopt the infant and have a son of their own.

Reggie found out he was adopted when the story about his arrest on the statutory rape hit the papers. His real mother, Mrs. Lillie Mae Thomas, kept a scrapbook of everything he did. She went to every one of his high school games and kept the programs. She got his records from every school he attended.

One day her son Robert came home from school and found her crying at the kitchen table. “I asked her why she was crying,” he said, “and she showed me the story in the newspaper and told me Reggie was my brother. She also made me promise never to tell anyone else about it.

“I was young,” Robert recalled, “and I didn’t understand what adopted meant. And she explained it over and over until I did.” Later that evening, Mrs. Thomas called Mrs. Harding, and Reggie overheard the conversation.

“He was furious,” his wife Nadine recalled. “He was very angry that Mrs. Harding had not told him about it sooner. He begged her to tell him who his real mother was, but she never would.”

****

But perhaps it all came too fast and easy for Reggie. “He got grown up too quick,” Bill Ervin said of Reggie’s high school days. “He got signed by the Pistons, and he got married and had a child right out of high school. He missed having fun and being free. He missed that, and he did it all later.”

Nadine Harding said, “From the day, I met him in high school, he always got what he wanted. He was a spoiled brat. I knew him well enough to know he was not as confident as he acted, but he got whatever he wanted. He didn’t get his diploma from high school, so we went to a school in Tennessee to finish up. I was pregnant, and he wanted to marry me. So he came home, and he did. It seemed like the whole world was his back then.”

Reggie didn’t play for the Pistons the year after he finished high school because the NBA wouldn’t allow it. So the young giant worked out with the Pistons and accompanied them to various high school basketball clinics.

“Everybody liked Reggie,” Billy Rodgers recalled, “even the kids. I remember one clinic up north. This six-year-old white girl followed him around everywhere he went. He talked to her and joked with her, and she loved it. At the end of the day, she hung onto his legs when he was supposed to go in and take a shower. She just wouldn’t let go. Reggie finally got away, and the girl told him she was going to tell her father that she wanted to marry Reggie. He shot back, ‘Honey, would I like to be there to see his face.’”

When the season started, Reggie went to play with the traveling Harlem Road Kings. The NBA finally changed its mind about Reggie by the middle of the next year, and he played his first game with the Pistons on Jan. 21, 1964 against Wilt Chamberlain and the San Francisco Warriors.

“Harding entered his first NBA game with 6:44 left in the second period with Detroit trailing 32-31,” a newspaper account of the game read. “Within seconds, he hooked in a field goal to send Detroit ahead, then got seven more points and five rebounds before the halftime, as the Pistons took a 49-44 lead . . .”

The Pistons won, 118-107.

Harding did well the rest of the season. He averaged 11 points a game playing 1,158 minutes in 39 games. He got 410 rebounds. The Pistons had a chance to get Willis Reed after that season, but they passed it up. Reggie Harding looked as good as gold.

Reggie Harding lived up to the Pistons’ expectations on the basketball court the next season. He averaged 12 points and 11 rebounds a game playing against men like Chamberlain and Bill Russell. He was rated the fifth-best center in the league.

Yet Reggie got into trouble with the law over and over again that year, and the newspapers tagged him, “The tall badman of the courts who spends as much time before a judge as playing basketball.”

****

By the end of the season, the Pistons had fined Reggie nearly $3,000 of his $15,000 a year salary and suspended him indefinitely. “After Reggie made the professional league,” his wife Nadine said, “he felt he was ‘The Man’ now, and no one had the right to tell him what to do. It was a very deep feeling he had. He hated authority. It’s deep in his childhood, that’s all I could tell about it. If the Pistons would tell him to wear a shirt and tie, he would show up in a turtle neck.

“It was more than that, too. All those other guys have been to college, and Reggie kept harping on that, that they thought they were better than he was. After the games, he would cry sometimes and say, ‘I just don’t belong.’ And he would go back to the pool hall with the guys and stay out all night with them. They were the guys he grew up with, he felt he was going to the top and would take them with him.”

Judge Edward Bell was an attorney when Harding played for the Pistons, and he became Reggie’s legal advisor. “None of the other players on the team had any use for him,” Bell said recently. “He told me that when the games were over, he would overhear the players talking about whose house they were going to. He said they never said anything to him about it, so he went out with his friends. I told him again and again: If these people were really his friends, they would not want him to go to blind pigs and places like that with them.”

But Reggie still did go out after the games with his friends. The first trouble he got into with the Pistons was when he was arrested for carrying a gun. He and some friends were going to the Twenty Grand to catch a good act. There was a line, and he didn’t want to wait in it so he walked to the front. The club’s bouncer told him to leave, and Reggie pulled what looked like a gun on him. The charges were dropped when police showed the “gun” in court. It looked like a gun, but it was a cigarette lighter.

“Reggie was funny about his size,” Nadine said. “I remember, sometimes when he would be walking out of Pistons games and kids would ask him, ‘Hey man, are you seven feet tall? Man, are you Reggie Harding?’ He would say, ‘No, I’m 6-5, I never heard of Reggie Harding.’ We would be shopping or out [and about], and people would come up to him all the time and ask if he was seven feet tall, and he would be nasty to them.

“I’d tell him, ‘Reggie, don’t do those people that way, they like you,’ and he would say, ‘They are making fun of me.’”

Meanwhile, Reggie’s real mother was attending every Pistons game and keeping all the scorebooks. Mrs. Lillie Mae Thomas also worked at the Sheraton Cadillac Hotel, where the Pistons had their main office. Ballplayers often stayed and ate at the hotel, and Mrs. Thomas saw her son there many times but never said a word to him.

During Reggie’s best year with the Pistons (the 1964-65 season), Mrs. Thomas came up and spoke to Reggie’s wife during a home game. “She had been drinking,” Nadine said, “and she came up to me and said, ‘Please don’t tell Reggie I’m here. I come to all the games. I’m his real mother. I don’t want him to know. But please do me one favor. Please make sure he comes to my funeral.’ She gave me her phone number in case I wanted to call, then she walked away.”

After the game, as Reggie and Nadine were driving home, Reggie kept asking, “Who was that lady? Who was that lady you were talking to?”

“I didn’t tell him until I got home, but I knew I had to tell him,” Nadine said. “I knew he would make me tell him, so I simply said, ‘She said she is your mother, Reggie.’ I told him not to call her, but he wouldn’t listen. He went straight to the phone and called her and talked for over an hour. I heard him say, ‘Why didn’t you let me know where you were all these years?’ . . . His mother was a very good-hearted person, but she was a heavy drinker.”

Reggie never found out who his real father was. His mother told relatives that he was a married man living in Detroit, but she never told anyone who he was. “Reggie told me once that someone had told him he had been shoulder to shoulder with his real father in a crap game,” Reggie’s brother Robert Hall said, “but he didn’t know for sure. He used to get very angry with me and accuse me of not telling him who his father was, but I didn’t know. My mother never told me.”

Reggie and Nadine started to grow apart. He would go out to the pool room or into the streets and hang around with men she didn’t care for and then come home at four in the morning and expect her to get up and cook him something. “I was always supposed to be waiting for him regardless,” Nadine said, “and I got tired of him being around.”

So Nadine took their two small children, Rachael and Reggie Jr., and moved out while Reggie was on a road trip. He found her and, in her words, “He just sat there and refused to leave until I promised to get back together with him. He missed his plane and game, and he was fined $500. He told them that he fell asleep, but he was here with us.”

“One thing you have to understand about Reggie,” Bill Ervin said, “he loved his kids. But he hated to admit on the streets that he loved a woman. He loved Nadine since he was in high school, but in his words, it was not cool to admit that, to let other people know.

“He was in my barber shop one day, and he found out Nadine said she was going to divorce him, and he sat down and cried. He cried like a baby, because he thought he wouldn’t have his family anymore.”

****

One morning, Reggie was in a local bar after he had been drinking all night. He saw a policeman writing him a ticket for his 1964 Thunderbird. “He got into an argument with the policeman and knocked the officer’s hat off. He was convicted of felonious assault of a police officer, even though the officer testified that Reggie had not hurt him. He was given a suspended sentence.

The Pistons gave Reggie the largest fine in the history of the NBA at that time: $2,000.

A week later, Reggie was arrested in a blind pig. He had spent the whole week making public apologies and telling people how he was going to be better and just concentrate on basketball. Both the Pistons and the NBA suspended him indefinitely.

“He would come in here, and I would talk to him,” Judge Bell said, “and I would tell him that if he wanted to make it big, he would have to stay out of those places. I told him he could possibly make $100,00 a year if he took care of himself, and he would say, ‘I can dig it, man, I can dig it.’

“But nobody could tell him anything. There was something missing that he seemed to be looking for.”