[Following up on our last post on Dr. J and the 1974 ABA-champion New York Nets, here’s a brief ode to their successors: the 1975 ABA-champion Kentucky Colonels. Like the previous article, this one was a little rough around the editorial edges. I’ve cleaned it up a little to help verbs match their subjects and so on. The tweaks shouldn’t hurt any feelings. This article, which appeared in Sports All Stars’ 1976 Pro Basketball annual, ran without a byline. But editorial comments aside, the following article offers a nice taste of the heated ABA rivalry that simmered and sometimes boiled over for nearly a decade along I-65 from Indianapolis to Louisville.]

****

“Lad-ees and gentlemen

And children of all ages

You’re about to see

The greatest show on earth . . .

In the center ring—our very own Kentucky Colonels. And for his first season in our Blue Grass State—ringmaster Hubie Brown.”

The crowd went wild. Pom-pom girls waved and danced.

Sideline acts performed.

And there was music, music, music.

Well, that’s almost the way it was in Freedom Hall, the night that the Kentucky Colonels went into the final championship game against the Indiana Pacers.

Just one sideshow away from the longed-for ABA championship. Game five. Kentucky leading three to one in a best-of-seven series. A big night for the Colonels, the state, the owners, and the championship-hungry fans.

This was Kentucky’s third appearance in the championship ring. They had lost to Indiana in seven games in 1972-73 and to Utah in a seven-game series in 1970-71. So the Colonels have been close, but they have never worn the crown. And the shimmer of success was near.

Kentucky and Indiana. Arch rivals for eight years. Geographically, the two teams are the closest of the ABA franchises. Both teams are still playing in the same city in which they originated. Both clubs have outstanding talent to match up and battle for the ABA banner.

Separated only by the 120-mile strip of Interstate 65, fans from both cities hustled back and forth with rivalry gusto. But neither fan nor foe left either arena without being thoroughly entertained, especially by the halftime events.

Indiana had starred in the “big tent” before, winning three out of seven league titles. In 1970, they won the championships by defeating Los Angeles. In 1972, they topped New York. In 1973, Indiana bested Kentucky.

Now, Indiana was looking for its fourth set of matching rings. Although Indiana finished third in the ABA’s Western Division (45-39), they disposed of second-place San Antonio, 4-2, in the opening round of the playoffs, then downed the Denver Nuggets in seven games.

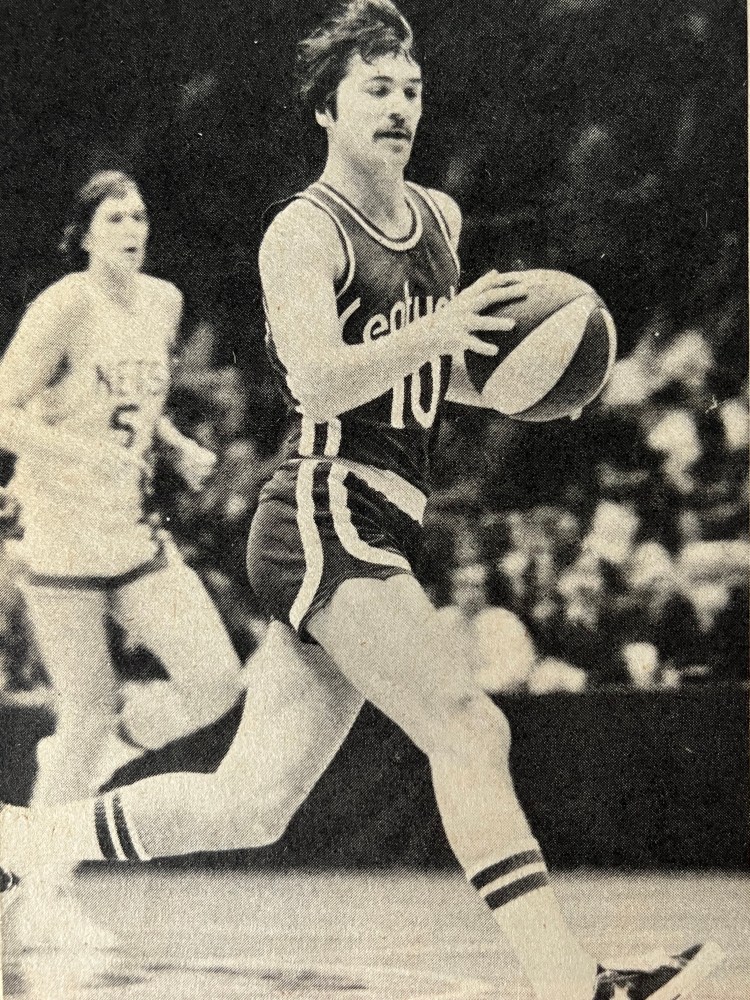

Meanwhile, the Kentucky team had shown more consistency. They ended the regular season posting a 58–26 mark, the same record as the Nets. The two teams then met in a tiebreaker on April 4 to battle it out for the Eastern Division regular-season championship. The Colonels took it, 108-99.

The Colonels moved through the playoffs with the greatest of ease. Taking first the Memphis Sounds, 4–1, then the Spirits of St. Louis with the same score in games. It seemed that the Colonels were going to do a repeat performance with the club from Indiana.

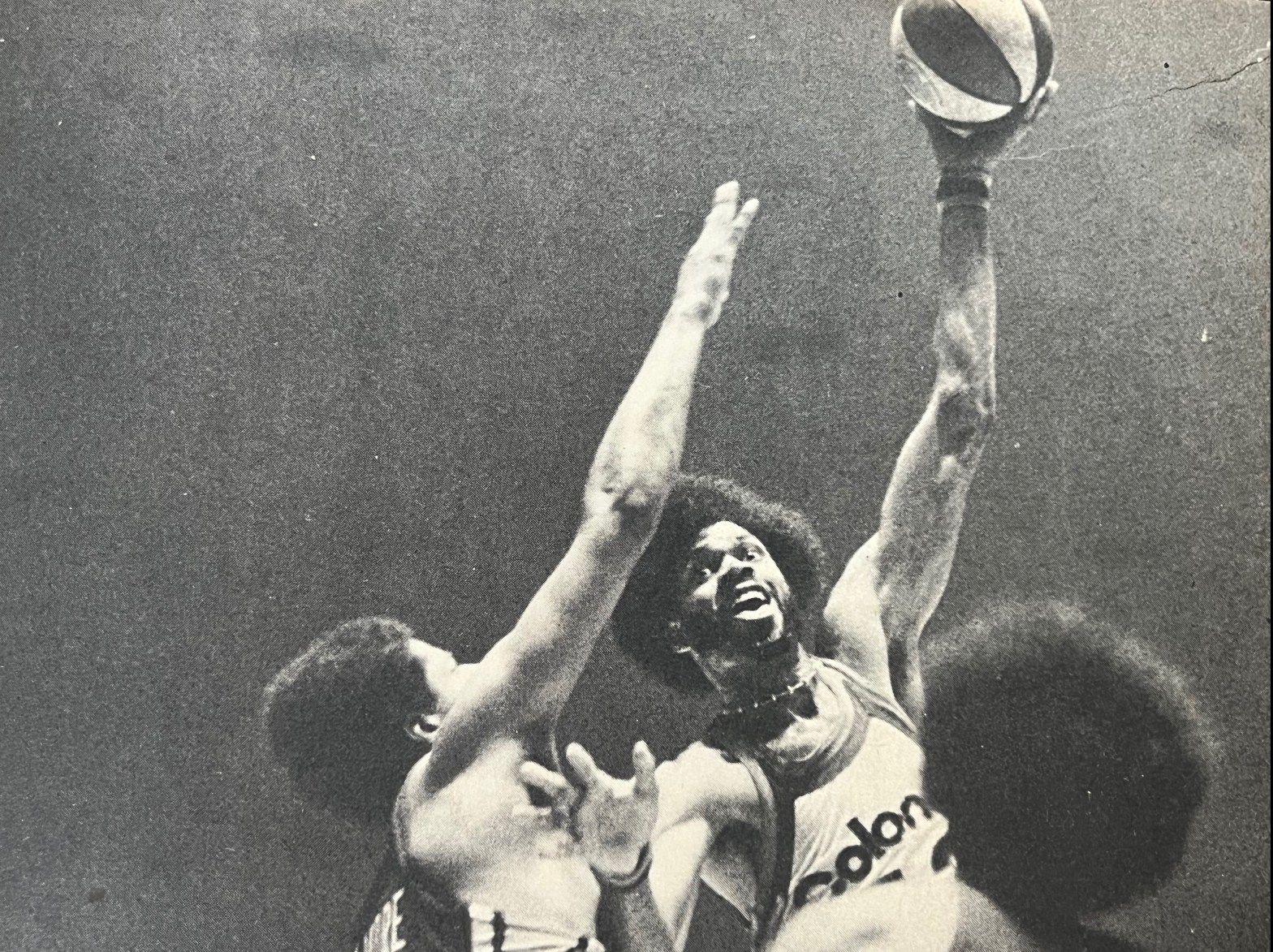

In game one, Kentucky stole the show by outscoring the Pacers, 120-94. It wasn’t the loss that bothered Indiana coach Bobby Leonard so much. It was the 26-point drubbing and Kentucky’s big dominating center—Artis Gilmore. Gilmore, far more aggressive than he’s ever been, had bottled up the Pacers’ inside game by eliminating all offensive moves by forwards Darnell Hillman and rookie Billy Knight.

Leonard took his team aside and talked it over. Planned strategy. What to do with Gilmore? Game two. The Pacers were able to get around Gilmore enough to even the score. But with two seconds remaining on the clock, Gilmore went in for a hook shot and made it, putting Kentucky ahead by two points.

Indiana got the ball. Billy Keller, “Mr. Quick,” aimed from downtown and answered. But the shot was called “no good.” Time had run out. The Colonels had taken their second straight, but not before all hell broke loose in Market Square Arena. The Pacers believed that the shot was on time, and the Indiana fans obviously felt the same way.

Tension was building, and so was the pressure on the Pacers to bring home a win. Game three again featured Gilmore and the Kentucky powerhouse. Gilmore scored nine points in the last five minutes of the game. He showed the Pacers what a big man can really do if and when he wants to. The Colonels won, 109-91.

Leonard’s team was used to winning. They had only missed one division or league title in six years. And Leonard had worked well and hard with his players. When he took over the club in 1968, they were in last place, and he led them to the division title. Known for his emotional outbursts, Leonard was said to have thrown ball racks and choked a referee. Now, what was he going to do with the Colonels?

Pacers’ super forward George McGinnis had played no less than superb. He would average 32.2 points per game, account for 286 rebounds, and notch 148 assists during 18 games of playoff action in 1975. George could do it all. But he had more than able help from his teammates, including outstanding performances from the rookies, Billy Knight and Len Elmore.

Leonard must have really let loose just before the fourth game. The Pacers took it, not easily, but they took it, 94-86. Coming back from a 3-1 deficit in a best-of-seven playoff series was not ruled out by the Pacers. But . . . there was still Gilmore and Dan Issel and Louie Dampier . . . and all the others . . .

The Colonels could do no wrong. They were even getting surprising assistance from their bench. During the playoffs, reserve forward Marv Robert contributed 151 points, guard Ted McClain added 180 points, and guard Bird Averitt dropped in 138 points.

Hubie Brown was proud of the progress he had made with the “never-a-title” Colonels. Perhaps equally relieved was Brown’s coaching predecessor Babe McCarthy, who was fired after the Colonels lost the ABA championship the year before to the New York Nets, 4-0.

But Brown accepted the challenge and left his assistant coaching position with the NBA Milwaukee Bucks. Brown had experience not only with a championship team, he knew what the big man in the middle could do on the floor, especially if he was the same height as Milwaukee’s Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

It was obvious that Brown had worked well with Gilmore. Unlike Kareem, Gilmore initially was not aggressive offensively, that is until this past season. Although his season’s average was not as impressive as it could have been, he had improved. Gilmore had boosted his scoring average from 18.7 points the year before to 23.5 points per game under Brown.

With Gilmore and his teammates on the rise, the Colonels had arrived at last to revitalize an almost defunct franchise. A couple of years earlier, season tickets and gate receipts had slumped. But with Ellie Brown now at ringside drumming up enthusiasm and launching ticket drives, attendance immensely improved and so did local support.

And now in game five, the Kentuckians’ most-entertaining basketball season was near its finale. There are no statistics available to estimate how many folks took the last run on I-65 from Indiana to see the curtains come down on the Pacers’ last game of the season. But the house was packed to the rafters. And if Pacers’ fans were there in large numbers, cheers from the home folks drowned out their loyalty.

The house lights brightened.

The performers were introduced.

The Kentucky folks sat back and watched the “greatest show on earth”—the Colonels winning the ABA championship.