[Pat Williams arrived in Philadelphia in the late 1960s as the personable, anything-goes answer to the 76ers’ box-office blues. Williams, still in his 20s, was considered a second coming of baseball’s earlier promotional genius Bill Veeck. Williams and his zany Veeckian promotions shook things up inside the red-seated Spectrum for a few seasons, then Williams bounced to Chicago to try his hand as the Bulls’ new general manager and boss of the team’s fiery coach, Dick Motta.

As featured in the article below, published in the 1972 Pro Basketball Almanac, Williams quickly helped to transform Chicago from a notorious pro basketball graveyard into winning NBA attraction. His Chicago success was short-lived, though. Williams would butt heads with Motta, who held more clout with the team’s ownership, and move on to become the general manager in Atlanta. When the ownership imploded and things went bad there, too, Williams jumped to much better days ahead in Philadelphia and later made many a magical memory in Orlando. Williams died last July. I’d wanted to acknowledge his passing but got sidetracked. Good for me, the other day I noticed this article from writer David Israel. I thought, “Why not?” So, let’s take a moment to remember the always successful, forever gracious champion of NBA flair, Pat Williams.]

****

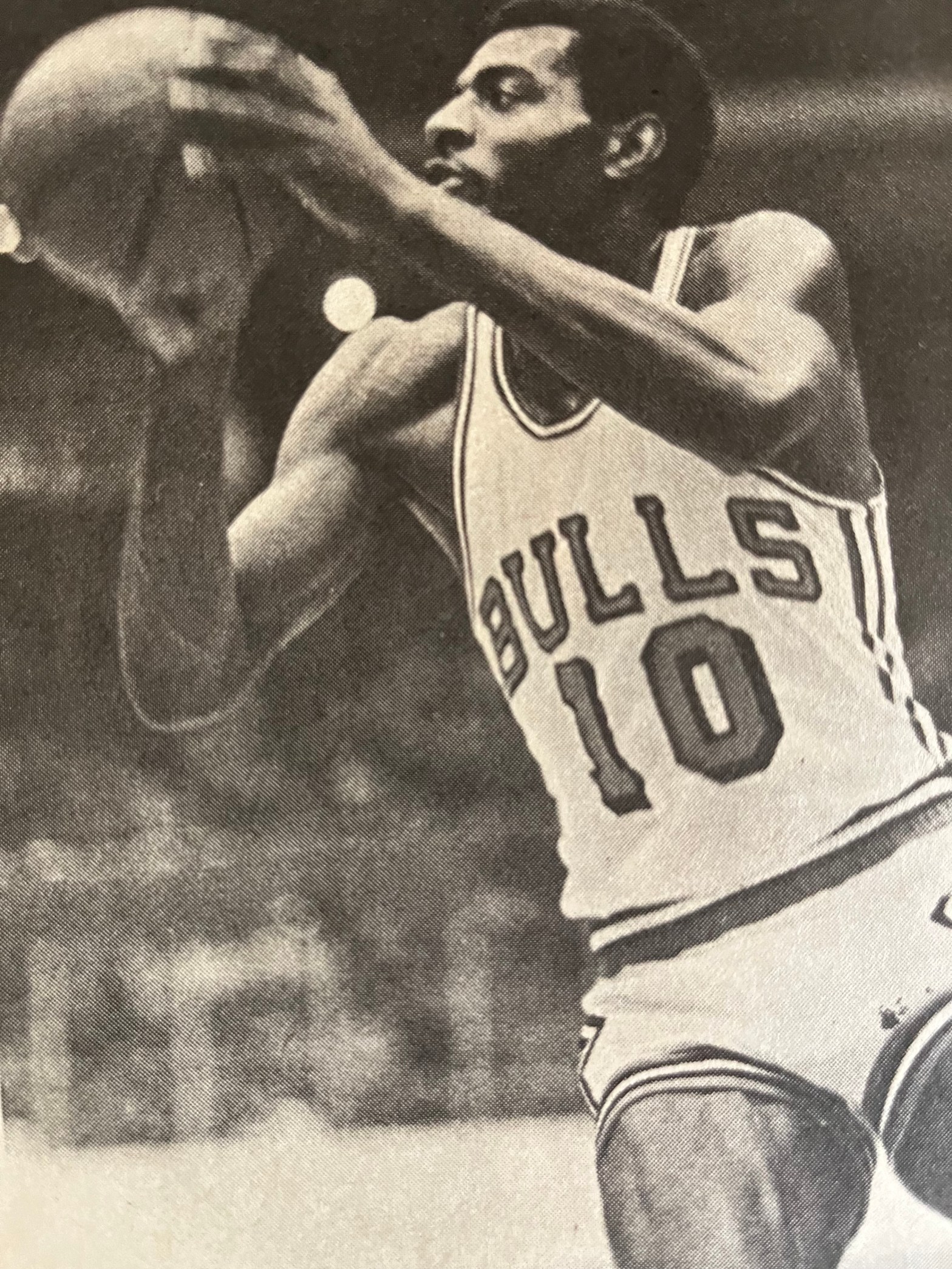

It had been this bad in Chicago: Home attendance during the 1968-69 season was so pitiful (3,790 per game) that the NBA Chicago Bulls scheduled eight of their home games for Kansas City for the following season. And then the Bulls’ top two draft picks of 1969, Larry Cannon of LaSalle and Simmie Hill of West Texas State, snubbed Chicago in favor of the ABA.

Apparently, NBA owners hadn’t learned their history and were doomed to repeat it. It looked like Chicago was about to lose its sixth pro basketball franchise. But then a miracle occurred: Pat Williams.

On September 1, 1969, the Bulls’ Board of Directors ousted a fellow director and business partner, Dick Klein, from his position of general manager and installed Williams, the 28-year-old protégé of Bill Veeck, as executive vice president-general manager. Studious and dapper, he’s a slick, but incorruptible operator.

Williams left his job as business manager of the Philadelphia 76ers fully aware of what he was getting involved in with Chicago. “I knew of the history of failure,” William says. “But I really couldn’t understand why pro basketball had failed here. Chicago is a good sports town. There is a population of 10 to 11 million to draw from. And with Indiana, this is a great amateur basketball area . . . Our job, I realized, would not be to awaken dormant pro basketball fans, but to create new ones.”

So, how has Williams created these new fans? Why have the Bulls averaged more than 10,000 fans per game since he arrived? Part of the reason is Williams’ Veeckian promotional flair, which made him minor-league baseball’s Executive of the Year 1967.

“We’ve had all of the regular promotional nights,” Williams says. “Basketball night, T-shirt night, and the like. But we’ve also had some unusual ones. Early last year, during the pro football season, we gave away footballs—the NFL doesn’t have to do anything like that to attract people.

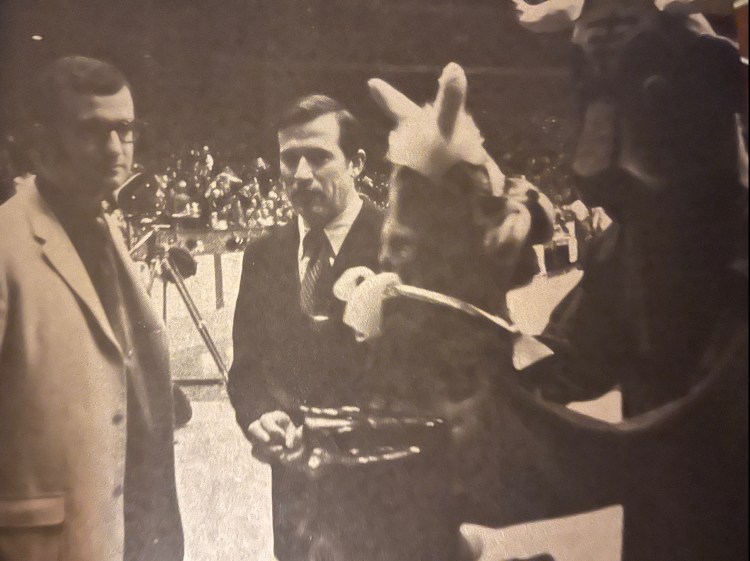

“We’ve also tried every kind of halftime entertainment. Once, we got Victor the Wrestling Bear. No one would go in with him, so I did. He pinned me in 10 seconds. That’s the last time we scheduled Victor the Wrestling Bear. And my favorite was Bill Veeck Night. We brought him back to Chicago, and then we had a midget jump center against our seven-foot Tom Boerwinkle. It turned out that the midget we used was the same one Veeck used 10 years earlier at a White Sox promotion.”

But it hasn’t all been promotional gimmicks. Pat Williams is a shrewd basketball man, whose deals and guidance helped the Bulls to the third-best record in the NBA last season (51-31), is a splendid judge of coaching talent, and is smart enough to listen to the right people. “When I got here,” he says, “everybody kept telling me all the things that were wrong with the club as it had been operated. But most of them also kept telling me that there was one thing right—Dick Motta.”

Motta, out of Weber State, had just completed his first year of NBA coaching when Williams arrived, having improved the Bulls’ record slightly, from 29 wins to 33. And very much to his pleasure, Williams discovered that Motta was determined to win—a man who wouldn’t tolerate imperfection.

“Motta is the toughest, most brutal competitor I know,” Williams says. “I’ve never been around a man who loses harder. He takes every loss as a personal insult . . . But I guess he’s a Jekyll and Hyde. After he unwinds and during the offseason, he is very low-key. But the minute a game starts, he is in another world.”

“I run a tight ship, but I’m not a tyrant,” says Motta, the NBA Coach of the Year last season.

A tight ship that has resulted in Chicago becoming a harmonious, selfless team that has succeeded, despite the fact that it lacked, until now, the superstar some think is necessary to win in the NBA.

It appears that the Bulls have that superstar today in a rookie. His name is Howard Porter, the one whose signing had more attendant mysteries than the acquisition of the Pentagon Papers. And although Williams denies that the signing of Porter took special effort or ingenuity on his part, you have to admire how he beat out all the cheats and devious operators by being honest with a confused kid.

“It really was nothing,” says Williams. “You’ve got to be on your toes all the time. I don’t believe that ‘nice guys finish last’ stuff. If you’ve got to be a snarling, cursing, evil man to succeed in this business, then I’m not interested in succeeding.”

Well, myths die hard. But Pat Williams is just about ready to put an end to all those wonderful little things that Leo Durocher and Red Auerbach have had us believing since childhood. And he’s going to do it without snarling, cursing, or being evil.

This nice guy just might finish first.