[In 1970, writer Pete Axthelm published his seminal book The City Game. It celebrated not only New York’s love affair with the NBA-champion Knicks but the city’s playground basketball culture, particularly the Rucker Tournament in Harlem. Wrote Axthelm:

“The Rucker Tournament is actually not a tournament but a summer league in which teams play one another through the weekends of July and August. Established in 1946 by a remarkable young teacher named Holcombe Rucker, it was originally intended mainly to keep kids off the streets and in school by encouraging them in both studies and basketball. Rucker’s idea was to give dignity and meaning to pickup games by adding referees, local publicity, and larger audiences; it worked, and graduate the Rucker tournament expanded to include divisions for young athletes from junior high school through the pro level.

Some subsequent basketball books have followed Axthelm’s lead and taken a slightly deeper dives into the short, but influential, life of Mr. Holcombe Rucker. For example, In the book Asphalt Gods, published in 2003, New York Times reporter Vincent Mallozzi wrote of Rucker, once called the Pied Piper of Harlem’s St. Nicholas Houses playground on 128th Street and Seventh Avenue:

Harlem’s Pied Piper, Rucker spent 14 and 15 hours a day in the park. He ate dinner there, his favorite meal, a Chinese dish of vegetables and rice with heavy brown gravy. Dessert always came in two courses: a cup of coffee followed by a cigarette. Kids arrived most mornings by 8:30, often finding some kids already waiting for him. For many of them, Rucker’s park was a home away from home. “Each one teach one” was his motto; it would later become the name of a Harlem youth organization run by his disciples.

All told, however, there’s still not a lot of information out there about the life of one of the true fathers of the Black playground game. To some meat to the bone, here is an article about Mr. Rucker and his tournament published in the September 1971 issue of the magazine Black Sports. At the typewriter is the Amsterdam News’ prolific sportswriter Howie Evans.]

****

In 1952, Holcombe Rucker, employed by the recreation division of the New York City Parks Department, organized a summer basketball league for youths. Today, though brother Holcombe has passed away, the league he started has become a summer institution in New York.

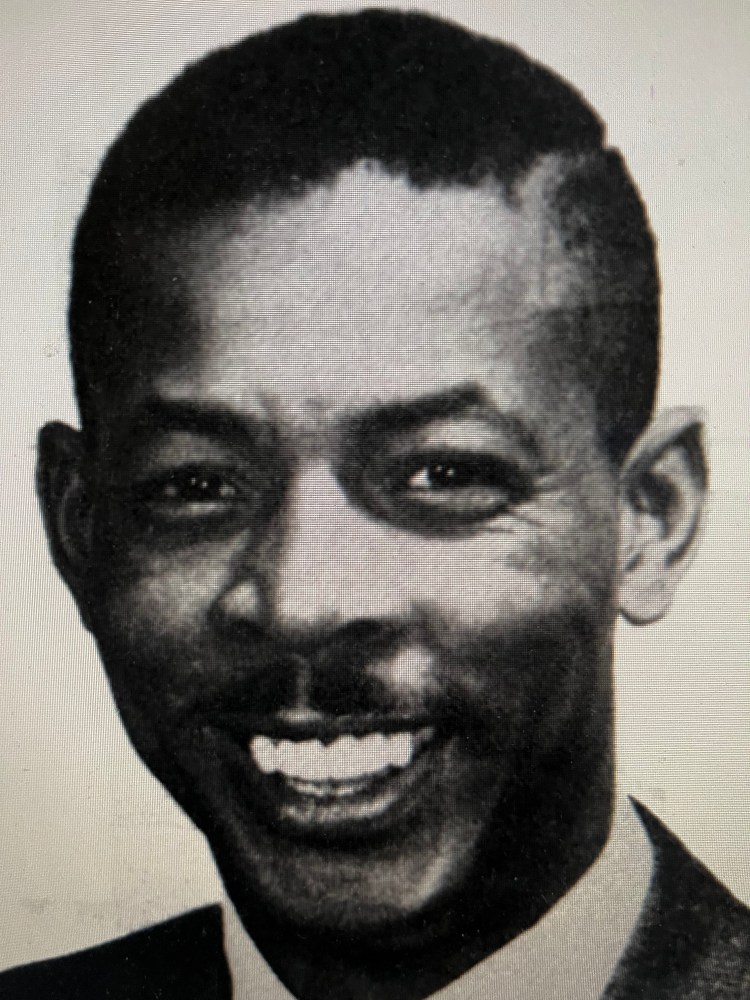

When Holcombe Rucker died of cancer in 1965, he had crammed two lifetimes of living into his 39 years. He was so involved in the lives of Black youths, he often neglected himself.

Back in 1952, long before people began urging Black students to attend college, Rucker’s theme was “go to school.” He preached “school,” night and day. He so believed in this doctrine that he himself returned to school at the age of 39 and earned a college degree.

His classroom was a dingy little park-house on Seventh Avenue near 127th Street in Harlem. On warm days, his classroom was a park bench or basketball court. He had notebooks to issue, no blackboards for demonstrations, and no rewards for those who did well. What he did have came from the heart. It was Rucker, one-on-one against every Black youngster who walked through the gates at this park, officially known as Saint Nicholas Park. But to anyone who knew what was happening, it was simply “Rucker’s.”

If you hung out at Rucker’s park, you received a daily lecture on staying in school and going to college. Fred Crawford, once an All-American basketball player at St. Bonaventure University and now with the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers, can thank Rucker for giving him the push that steered him into college.

“I don’t really remember when I met Rucker,” confessed Fred. “He might have just walked up one day and said, ‘Hey.’ I knew who he was and that he was doing good things for a lot of kids. I used to go down to his park every day when school was over. He was always there rappin’ with the guys. He was the type of guy you could really talk to, know what I mean?

“Today, school is the thing. But at that time, it was just beginning to catch on—getting a scholarship and going to college was not very common. He kept education on your mind. That’s all he talked about. When we came down to the park, Rucker would start talking to us about ‘this’ guy and ‘that’ tournament. We would stand there with our mouths open.

“I started playing in the Rucker Tournament when I was in high school. I was standing around the yard, and Rucker came over and said, ‘You’re on this team.’ I guess he saw I wasn’t with anyone and wanted to hook me up. He was like that. He didn’t wait for you to come to him.

“You really have to dig on the magnetism of the man. He made things happen. Because of the tournament, a lot of guys were always mad at him, and some even threatened to beat him up from time to time. But hey! Nobody ever beat up Rucker.”

Observers remember Freddie Crawford as a being a big, agile youngster who questioned his own talents. “Yeah, that’s right,” vouches Fred. “I didn’t overcome that until the day Rucker pulled me aside.

“Of course in those days, everybody was nuts about Tony Jackson (St. John’s University and the ABA’s New York Nets), Tom Stith (St. Bonaventure and New York Knicks), and Willie Hall (St. John’s University). So I was saying to Rucker as he pulled me aside, ‘Man, I wish I could be that good.’ He said there’s nothing to prevent you from that. You’re that good now.’

“I said, ‘Wow!’ This guy thinks that of me? After that, I didn’t care about nobody on the playground.”

And so, as the tournament grew, college coaches found the Rucker Tournament to be developing ground for young talent. Cal Irvin, the head basketball coach at North Carolina A & T University, said, “I have found the Rucker Tournament to be a great reservoir of talent. I remember, at its conception, how I thought it was one of the finest things that could possibly happen.

“It has produced so many fine athletes and proven to be a medium through which many kids have been given the opportunity to go to college. The Rucker’s is without a doubt one of the finest high school tournaments in the country. Those people who have continued the program should be given the highest praise. It is something New York City should be proud of.”

New York City—its park department, in particular—turned its back on Rucker. It was almost like he didn’t exist. They gave him no help. There were times when he would have to borrow basketballs from the kids. Other times, he fished through his pockets for loose change to buy a whistle.

Though thousands of people came to view the games, the city refused to erect portable bleachers for their comfort. Meanwhile, up and down lower Fifth Avenue portable bleachers were rotting in the sun.

Rucker spent 14 and 15 hours a day in his park. He was like a pied piper. As early as 8:30 in the morning, the kids would be waiting for him to come and start something. They never left until dusk. For many, it was a home away from home.

Charley Hoxie, former Niagara University All-American, was very close to Rucker and played many years in the Rucker Tournament. Hoxie recalled this about Rucker: “This thing about community involvement,” said Hoxie, “had not yet become popular. But Rucker even back then was involved with the community. It was very evident. He was always talking with the kids and doing things for them. Everything was for the kids.”

Charley Riley, former star at Winston-Salem State University, admired the way Rucker dealt with kids. “He had a way of handling kids. If a youngster had a problem, he didn’t let him go until they had talked about it. He dealt with the total individual and was the kind of guy who would miss paying a house bill to put up an entry fee for a team of kids in a tournament. That was Holcombe.”

“Those days . . . the park, the tournament, I’ll never forget them,” insisted Crawford. “It was the place I wanted to be. I was there, even when no tournaments were going on. We spent every day in the park. When it got dark, Ernie Morris, another guy Rucker helped, and I would walk home. There were times when we would eat lunch, drink sodas, munch potato chips, lay back and sound [out] each other. Rucker was always there. But he wasn’t there . . . if you know what I mean. We did and said what we wanted. It was no big thing.”

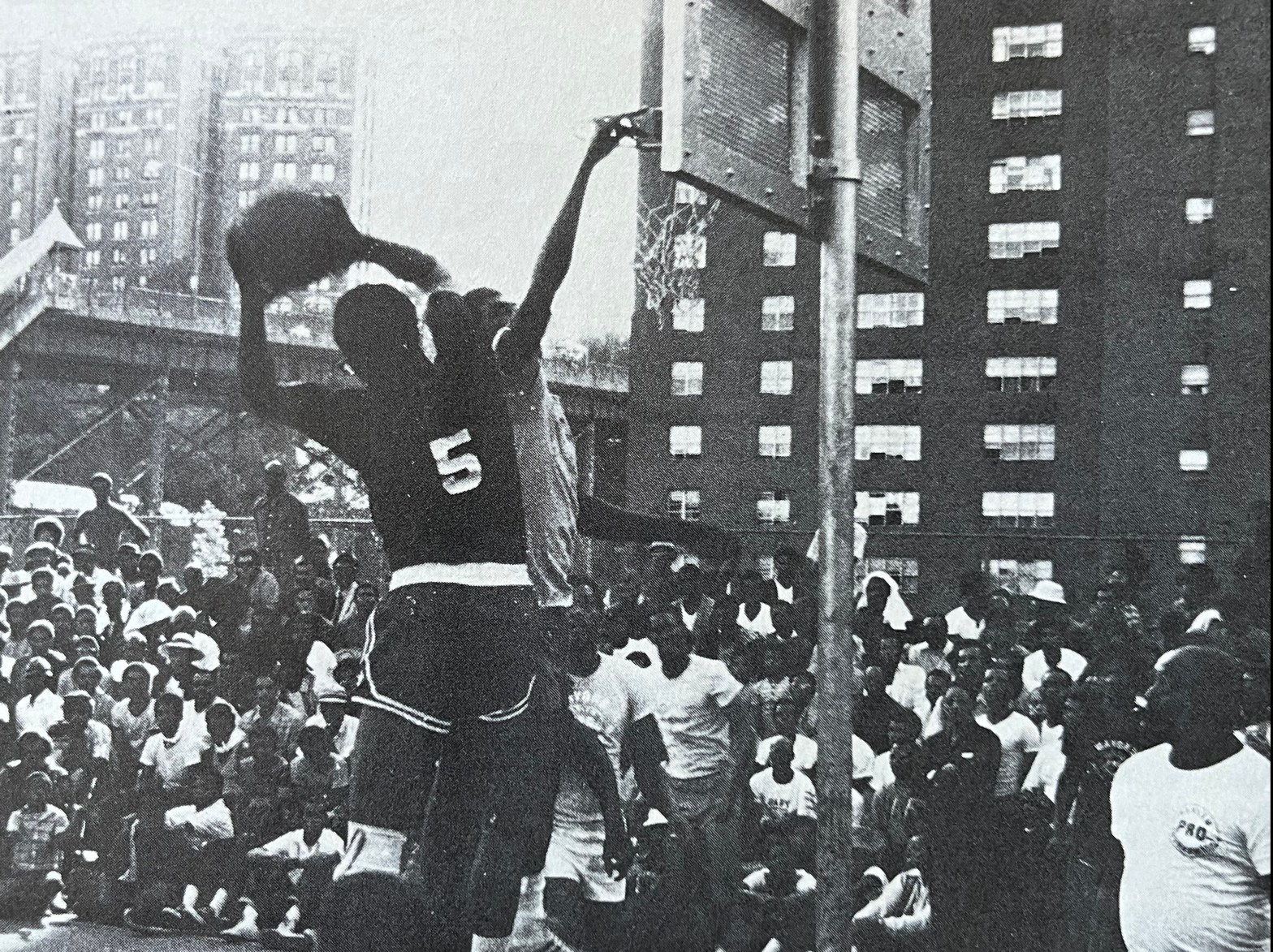

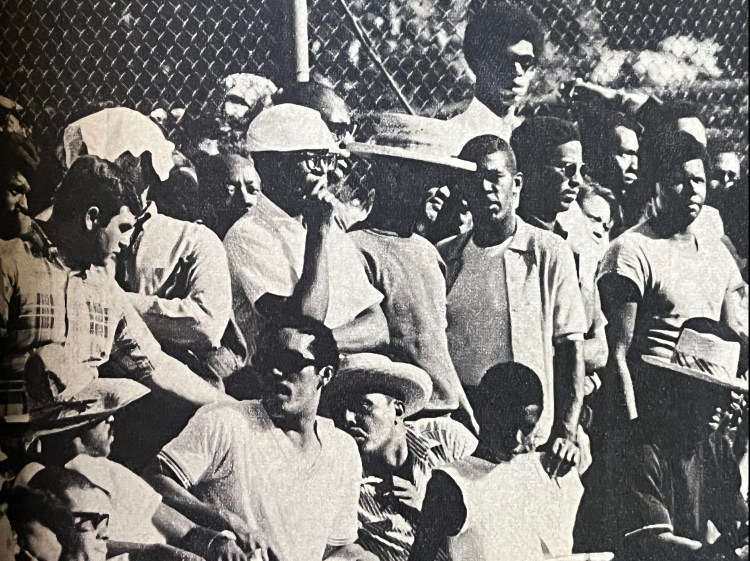

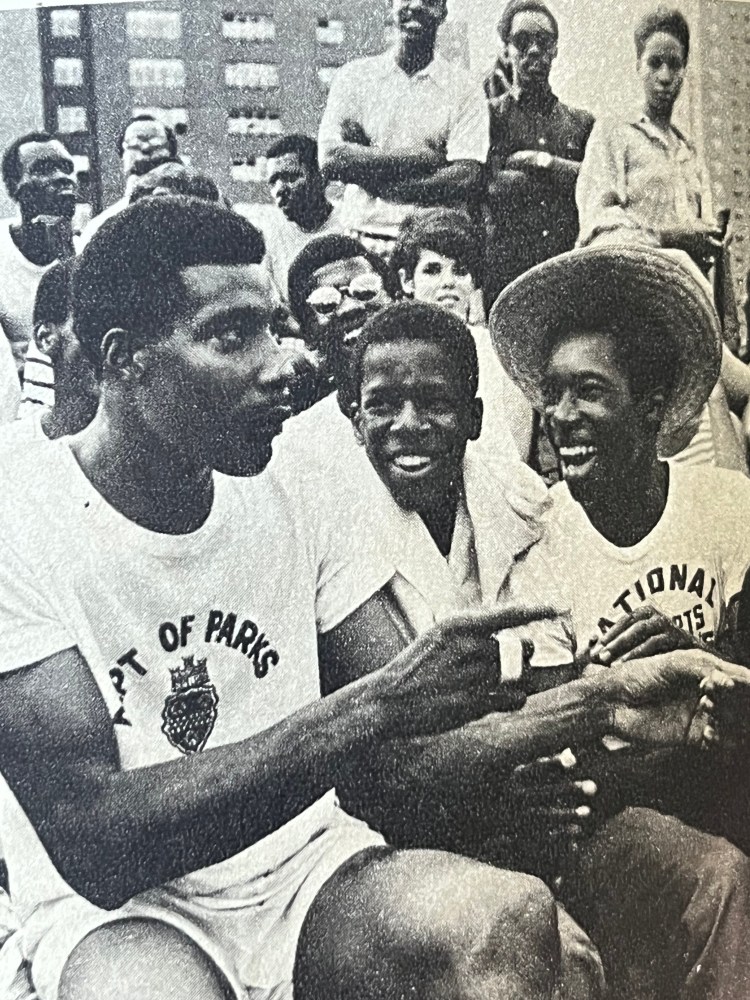

On the weekends, when all the big games were held, Rucker’s park resembled an amusement park without the rides. Push cart vendors sold everything, from beer to ice cups. Small children hung from the fences, short pretty girls stood on boxes, and people hung out of the windows with the best views of all the action.

Adding to the scene were the scores of cars, double and triple parked as far away as five and six blocks. On these weekends, patrolmen on the beat from the 32nd police precinct simply stashed their tickets and wandered over to catch some of the action.

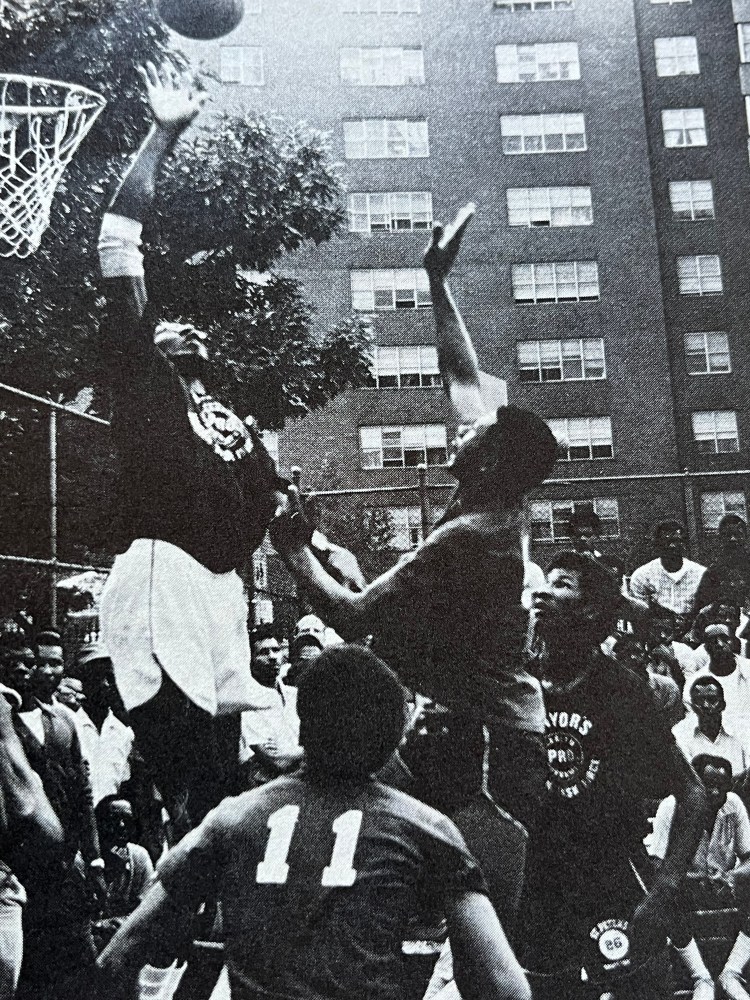

Some memorable things happened in the band-box park, adjacent to Saint Nicholas Houses Project. In 1960, Connie Hawkins, now with the NBA’s Phoenix Suns, and Roger Brown, now with the ABA’s Indiana Pacers, were members of a Brooklyn team that was playing for the Rucker high school division championship. At the time, Connie and Roger were being sought after by just about every college in the country.

When word of the game spread, people began piling into the park as early as 10 a.m. to get a good vantage point. By the end of the first quarter, the game almost had to be canceled for lack of playing space. The crowd had virtually reduced the court to a bowling lane.

That same summer, the Philadelphia playground All-Stars played the New York All-Stars. Traffic was stopped north and south along Seventh Avenue between 125th and 135th Streets. It was at this point the police detoured motorists because people going to the game had just driven as close to the park as possible and then jumped out of their cars and split for the game. The fun really began when everyone left at the same time.

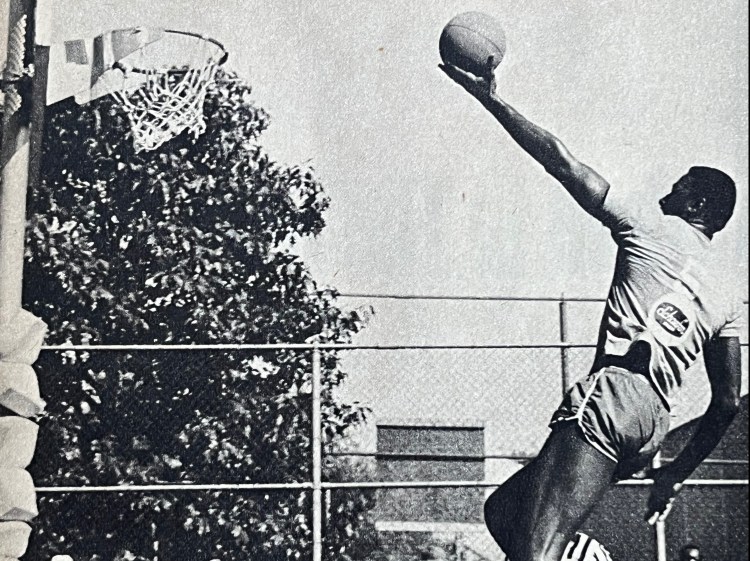

By 1955, the tournaments had outgrown the little park. But this became more evident when, in that same summer, Rucker introduced summer professional basketball to New York City. It was an overwhelming success, and before long, became the tournament’s top draw.

To many people, Rucker appeared to be disorganized. The fact that he never had a schedule on paper, the fact that he never knew who was going to officiate the next game, and the fact that he had no money and seemingly no monetary resources lent much to their argument.

Bruce Spraggans, who spent the first 22 years of his life in the South, came north in 1961. “I couldn’t believe that one guy did what Rucker was doing,” said Bruce. “Running back and forth between the kids and the pros, it was just unbelievable. All I can say is that I got more exposure playing here in the Rucker Tournament than I did in my four years at Virginia Union University.”

Spraggans, out of Burton High School in Williamsburg, Virginia, came to the city through Ed Simmons, a legend on the New York playgrounds. After one summer in the Rucker Tournament, Spraggans picked up enough savvy to make the Eastern Pro League with Wilkes-Barre. He later became one of the first players to sign a contract with the ABA and played two years for the New York Nets, then known as the New Jersey Americans.

Emotions ran high when “The Ruck” passed. Scores of people, led by Harlem youth worker Rollie Edinburgh, formed a committee to keep the tournament going. It went about the usual business of setting up the tournament. But the committee members couldn’t understand why it was taking 50 of them to do what one person had been doing for 15 years.

They called themselves the Holcombe Rucker Memorial Committee. Their aim: Seek government assistance to continue the program on a larger scale.

Government dollars were available—but not if the professional segment of the tournament was included in the proposal. Bob McCullough and Fred Crawford, not fully understanding what was happening with the government, thought the professional tournament was being ignored.

They formed a group of individuals who wanted to see the pro division continued. The split became final when the Rucker Committee moved the youngsters on the east side to Mount Morris Park, where they are today. In between, a turn of events—perhaps more personal than professional—resulted in the professional division having to change their name to the Harlem Professional Basketball League. There was much bitterness.

The years have passed, and with them, much of the bitterness and misunderstanding. It appears that the air is now clear enough for both sides to work out their problems. Says Fred Crawford: “The Memorial Committee is doing a great job with the kids. I guess you can say I have matured to the point that I can sit down with others and have meaningful dialogue so as to bring things back together the way they were when Ruck was living.”

Of all the people Holcombe Rucker helped, perhaps the greatest accomplishment was turning Bob McCullough around. “Mac,” now the commissioner of the Harlem Professional Basketball League, remembers the first day he met Holcombe Rucker.

“I went to try out for St. C, a church team Rucker was coaching. After the try-outs, all the guys were crowded around Rucker yelling to be picked. I stood on the side. When I saw he was being hesitant about selecting, I raised my finger and said, ‘I scored four points.’ He answered, ‘I’m not interested in points. I’m interested in guys who can play the game.’ He didn’t pick me for the team, and I sort of drifted away. At the time, I was in Douglas (139) Junior High.”

Mac felt bitter and rejected, but that was not the last McCullough saw of Rucker. “Yeah,” sighed Bob, “that really hurt. I stopped, practicing and forgot about the team. It wasn’t important to me anymore.

“I got involved in other things—you know, gang wars, clubs, hanging out. Then I moved around the block to where the church was located. But I still wasn’t interested in the team. While I was fooling around in the streets, I got into trouble with the police (gang fight). They had me up at 32nd precinct, and Rucker came with my father and Mrs. Lorraine Younger, who was like my mother, to help me.

“I wondered what Rucker wanted. I didn’t even play on his team. He talked with the police and left. The next day, I went to court. When it was over, I tried out for the team and made it. I later found out that Rucker put me on the team to keep me out of trouble. At the time, I was only 13 years old.”

As “Mac” grew older, Rucker stuck right with him. Bob had some bad experiences at Harren High School, but Rucker was always there to help and guide him. Along with Ernie Morris, now, a teacher in New York City, McCullough received a scholarship to Benedict College in South Carolina. Ernie, with Rucker’s help, had finished high school at Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina.

McCullough had a great college career and was then drafted as a free agent by the NBA’s Cincinnati Royals. At the same time, Oscar Robertson had been a hold-out, and things were going great for Bob. But when Oscar came to camp, McCullough was dropped. It took Bob a long time to recover from that experience.

The Rucker Tournament today is part of a citywide summer basketball program with a tournament in every borough. It’s the one with “all the tradition and prestige,” said Jerry Ward, a 19-year-old youngster from East Harlem, explaining what the Rucker Tournament means to him.

“Ever since I started thinking about basketball, I have wanted to play in the Rucker’s. That’s the one all the best guys play in, and everybody likes to play against the best. The biggest thrill I got was when my team won the tournament a couple of years ago.”

“That’s the way it is,” claims Floyd Layne, head basketball coach at Queensborough Community College. “Rucker has motivated thousands of youngsters. He helped get them into school. He motivated them to do bigger and better things in life. He was—and remains—a legend, tremendous person. No one can say enough about him.”

Ed Warner, all-time great basketeer from City College of New York (CCNY) and the first Black basketball player to win the Most Valuable Player award at the National Invitational Tournament (NIT), commented, “The work that is being carried on by the Holcombe Rucker Committee is great. We should pay tribute to a man who has done so much for and in the Black community.”

The professional part of Rucker’s brainchild started in 1955. It’s now being continued by McCullough and Crawford. Last summer, there were weekends when over 8,000 people braved the New York heat, and players like Charlie Scott, Dave Cowens, Emmette Bryant, Dave Stallworth, Cazzie Russell, Tiny Archibald, Ollie Taylor, and Barry Leibowitz played their hearts out for those people. Every game appear to be for the championship, but it was all for fun.

There is a lot of pride out there. The big-time pros can’t come out jivin’, because the not-so-well-known brothers will eat them alive. Guys like Ron Jackson, Herman (Helicopter) Knowings, Joe Hammond, Pee Wee Kirkland, Tony Greer, Walter Ward, Tommy Mitchell, and Walt Simpson can hold their own against anyone in the basketball world. In the past years, people in the community who have taken verbal potshots at the tournament often question the credibility of the professional players in the Harlem community. They want to know what they are doing to help the community other than playing ball?

“That really irks me,” says a smarting McCullough. “The pros who come here to play have an immediate responsibility to their families and communities. Most of the professionals are not from the Harlem community. They are here only because of Freddie Crawford’s invitation to them.

“I am sure they would not mind doing what they can, but Harlem is not their community. It is our community and our responsibility. There are other ‘Harlems’ around the country. These pros who come here have their homes, and I am sure they would be there doing something.

“Yet, they are willing to come to Harlem and help in their own way. The pros are contributing just by being here and presenting a positive image to the kids. Instead of seeing them on the television screen, they see them in person.”

One has to wonder if there are moments when Fred and Bob feel like throwing the ball up against the backboard and walking away. “Yeah,” admits Fred, “but Mac always talks me into coming back.”

“Now we have more sophisticated ideas, and we’re really going to do our thing. Now we want to go ahead with things like building a camp, so that we can take the kids away for a week or two every summer. That’s our immediate goal.”

The name of Holcombe Rucker means nothing to millions of people around the country. But to college coaches and people like Fred Crawford, Ernie Morris, Bob McCullough, and indeed the Harlem community, the name of Rucker meant everything. When asked what kind of man Holcombe Rucker was, Pelham Fritz, present director of the Rucker Summer Basketball Tournament, summed it up very nicely: “Holcombe Rucker was a man—a man in every sense of the word.”