[Entering the 1970s, Dick Vitale was known as the successful young coach at East Rutherford (N.J.) High. Or more to the point, Vitale was the guy with the big personality who’d discovered, groomed, and now coached the 6-feet-9 Les Cason, America’s consensus preseason choice as the 1971 prep player of the year.

Vitale, a sixth-grade teacher by day, thrived in his other role as East Rutherford’s varsity head coach and influencer of Cason’s college choice. But Vitale soon raised eyebrows by announcing that Cason’s senior year also would be his last at East Rutherford. “I haven’t signed anywhere,” Vitale told a curious reporter. “Honestly, I’m hoping to go to college coaching next year. I love basketball, and I’d like to coach ball. I’m 30 years old, and I feel if I make a break from high school coaching, it should be now.”

Cason later asserted that Vitale had used him to lobby hard for a college coaching job. “Dick Vitale is a pusher,” Cason later grumped. Vitale has vehemently argued otherwise. While the truth probably lies somewhere in between, there is no dispute about one thing. As the 1970s came to a close, Cason had become the poster child for the celebrated top recruit gone terribly bust, a tragic victim of himself, sleazy college recruiters, and now the call of the streets. While Cason crashed, the uber-ambitious Vitale catapulted through the collegiate ranks and landed his self-described dream job as an NBA head coach.

His NBA dream didn’t last long. Vitale “got the Ziggy” after a little more than one NBA season, then doubled right back to the college game to build his enduring legend as the motormouthed, crazy-as-a- fox coach and commentator named “Dickie V.”

In the following article, published in the October 8, 1978 issue of the Detroit Free Press, journalist Charlie Vincent profiles Vitale’s jump to the Pistons after his brief and very successful tenure at the University of Detroit. After Vincent’s article, a few post-mortems follow on why Vitale’s NBA days were numbered.]

****

Summer darkness had just settled around the big colonial-styled building in the Detroit suburb of Southfield that serves as radio and TV studios for WXYZ. A lone figure scurried through the parking lot, giggling as he went. He paused for a few moments behind each car, then moved on to the next.

“Dick Vitale!” a voice suddenly called through the darkness. “What are you doing? What kind of pro basketball coach goes around putting bumper stickers on automobiles.”

“Baby, that’s what makes me unique!” the Detroit Pistons new head coach unabashedly responded. “They may not know me around the National Basketball Association now, but they will, baby, they will!”

Though it’s doubtful any coach in the history of the NBA has ever before personally plastered bumper stickers on cars, it did not seem unnatural for Vitale to invade the parking lot of his most consistent local antagonist, Channel 7 sportscaster Al Ackerman, with an armload of “Detroit Pistons ReVitaleized” stickers. The Pistons’ new coach is in many ways an enigma: flamboyant and bizarre in is public style, but conservative and fundamental in his coaching.

Just a few days before, his lifelong dream had been realized when the Pistons named him to take charge of their humdrum team for the move from Cobo Arena to the Pontiac Silverdome. The temptation to emphasize his new stature—especially for Ackerman’s benefit—was irresistible.

“He says I had been blatantly campaigning for the job for five months,” Vitale says of Ackerman. “That’s not true. I’ve been campaigning for it all my life . . . I think I represent the American dream, that it can happen.”

Since childhood, Vitale has dreamed of becoming a professional basketball coach. Last December, that dream became almost an obsession; the Pistons fired Herb Brown just two weeks after Vitale himself had tearfully resigned as coach at the University of Detroit, because of intestinal bleeding.

Vitale has a history of intestinal problems and two years ago spent a couple of weeks in intensive care at St. Mary’s Hospital, while doctors tried to determine if his problem was bleeding ulcers or cancer. They eventually diagnosed it as ulcers. When the bleeding began again last November, Vitale, without consulting a physician, decided it was time to give up coaching.

That decision, however, did not stand for long. The chance to fulfill his lifelong dream of becoming a pro coach, combined with the discovery that his condition was not quite as serious as originally supposed, foisted Vitale into contention for the Pistons job.

****

Over his five years in Detroit, Vitale has evolved from an unknown to a curiosity to a genuine hero. When he resigned at U-D, the Detroit Free Press editorialized: “It was as though the weather bureau had predicted a darker, more unpleasant winter for the Detroit area. With Dick Vitale unable, because of health problems, to continue as basketball coach at the University of Detroit, the winter suddenly looks bleaker.

“When Dick Vitale first showed up on the Detroit sports scene, we thought he was all mouth. By the time he announced . . . that he would have to resign as U-D’s coach, we had come to believe, with most Detroiters, that he was all heart. Unfortunately, there is more to it than that, and the intensity that made him a winner has also now made him ill.”

With the stunning success of U-D as his most impressive credential and the almost unanimous support at the Detroit media (Ackerman, excluded, of course), Vitale was the front-runner for the job from the outset. But he worried about it endlessly.

He’d call acquaintances on the city’s daily newspapers to ask what rumors they had heard, while Bob Kaufman, who has since resigned under pressure, finished out the season as general manager/coach. “It doesn’t look good,” he’d say one day, despairing his chances. But the next day, he’d be on the phone outlining all his plans for the new, dynamic Pistons.

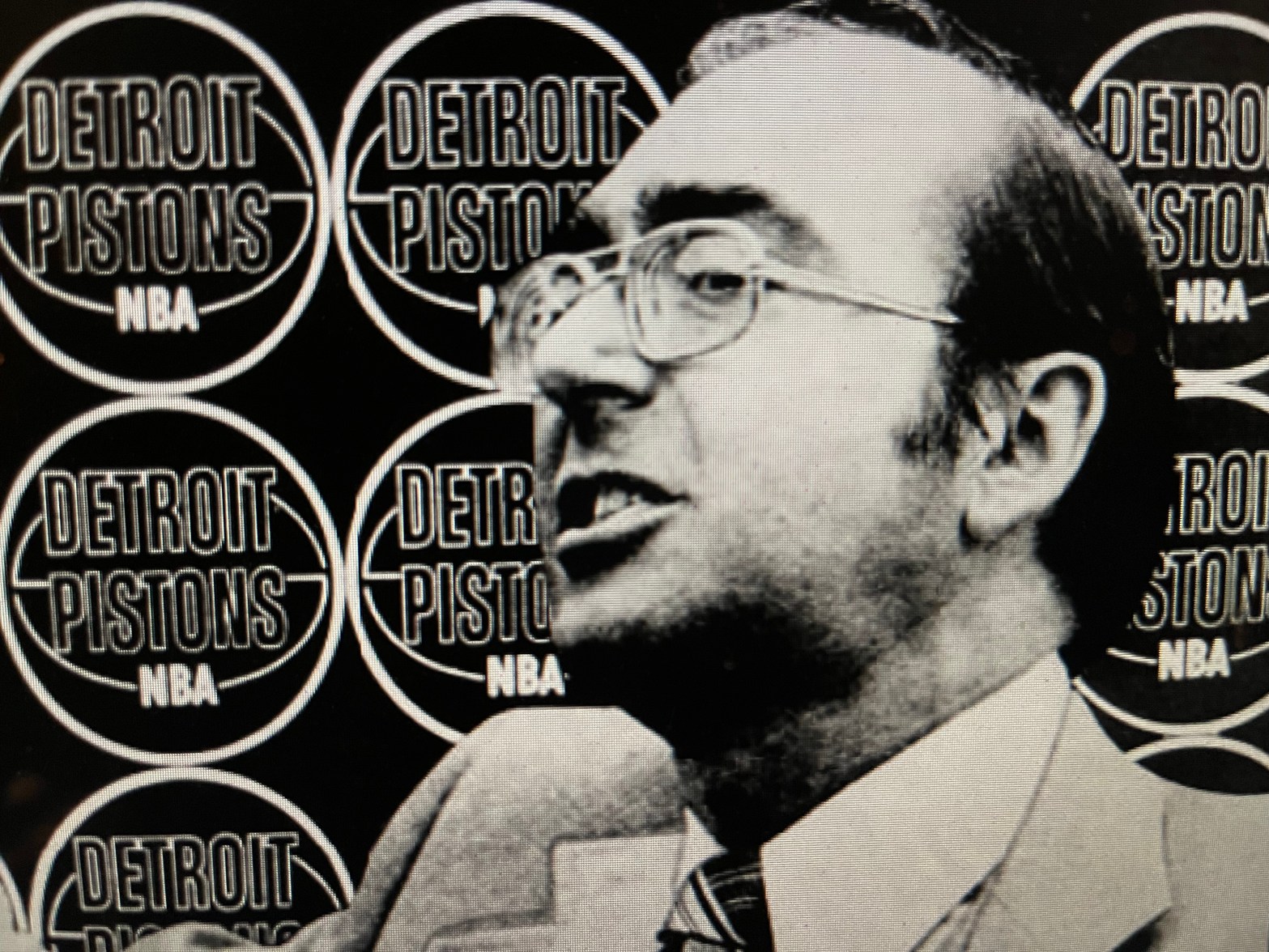

And when the choice was finally made, there was Vitale standing behind the lectern at the Silverdome, thanking the media and his players for making it possible for him to sign a three-year, $100,000-a-year contract and to drive a new Lincoln Continental.

It was a big step up from just a few years before, in 1973, when Vitale made the move from assistant at Rutgers to head coach at U-D. For Vitale, Detroit was the land of plenty. He had been earning only $11,000 at Rutgers, and when U-D told him he could have the job here, he felt confident enough to say: “That’s fine, but I’ve got to have $15,000 a year.”

Oh, responded the people who control the U-D purse strings, we were planning to offer $17,500. “It all happened in the city of Detroit,” he said after the Pistons named him their coach. “The people of Michigan have really treated me great. It’s unbelievable.”

****

Detroit has not been precisely paradise, however. “The first time I was a guest at the Detroit Sportscasters luncheon,” he remembers, “Vince Doyle introduced me as ‘Vinny Vitole.’ Then another guy came up and introduced himself as Al Ackerman from Channel 7. He told me he wanted to do a little film with me. I went over to Lorraine and said: ‘Honey, they’re going to put me on TV.’

“Well, Ackerman comes over and puts his arm around me and flashes this great big smile, and when the cameras start rolling, he looks at me and says, ‘Dick, how does it feel to have this job . . . a job that belongs to another man, a Black man, Freddie Snowden.”

For one of the few times in his life, Vitale was speechless. Soon, though, he found the race issue raised so often that he had to face it squarely. Vitale responds by mentioning the day he was born, back in 1940. “I woke up one June 9th, and I was white,” he says. “Terry Tyler woke up, and he was Black. So what? There’s nothing I can do about it. I’m white, some people are Black.

“When I first got to U-D, I met with the team, and I told them, ‘Let’s forget color of skin. I want no Blacks sitting here, and no whites sitting there. If we can’t sweat together and bust our rear, ends together and unite together in a common goal, then, well . . .’”

His team’s accomplishments are well documented: records of 17-9, 17-9, 19-8, and 25-4; and an NCAA tournament invitation in 1977. And following his resignation as U-D’s coach, the 1977-78 Titans that Vitale organized were led by his successor Dave Gaines to another 25-4 season and a place in the National Invitational Tournament.

But he has had more than his share of off-court trials. “I got some vicious hate mail,” Vitale recalls of his early days at U-D. “In the Black community, there was resentment of a white guy becoming popular with Black kids. I get phone calls at home, saying, ‘Go back east, you white motherfucker.’ And then there were the suburban fans who wrote and said I had too many Blacks on the team. They’d say, ‘How do you expect us to support you?’

“I gave up, trying to please everybody. I couldn’t do it. I just went out and tried to do my job, because I believe the majority of the people in Detroit—the majority of people in this country—judge people by their efforts.”

****

If effort is the criterion for value, Vitale must be judged an unqualified success. At U-D, he was coach, recruiter, athletic director, public relations officer, fundraiser, speechmaker, and counselor to athletes with problems. With the Pistons, that list of duties has been trimmed to just two: coach and maker of speeches—long, colorful, salty speeches, usually dealing with motivation.

But Vitale has hardly held back. Consider this week in early September, during which he was trying to slow his speaking schedule to prepare for the opening of practice: he appeared on the Jerry Lewis Telethon on Monday; spoke to the Novi Board of Education and a Pro-Keds Clinic on Tuesday; appeared on a local TV morning talk show and at the Detroit Sportscasters luncheon on Wednesday; spoke to the Flint Kiwanis luncheon on Thursday; and addressed the Greater Rochester Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Accountants on Friday.

And on the seventh day, he rested.

The Pistons attribute their new season-ticket sales record to the coach’s constant visibility. The move to suburban Pontiac was a gamble. Traditionally, the Pistons have drawn from the inner city. Now they must sell themselves to Oakland County suburbanites, who seldom came to downtown Detroit for anything but business, while also trying to convince their old fans in Detroit and the downriver suburbs 50 miles from the Silverdome that Pistons basketball is worth driving through a Michigan winter to see.

So far, the gamble appears to be paying off. The Pistons averaged just 5,448 customers a game last season at Cobo Arena. And they projected that their 1978-79 season-ticket sales for the Silverdome will approach that mark.

****

Vitale is a workaholic. His non-stop drive to succeed may stem from the fact that he never made it as a player himself. An infection at the beginning of his junior year in high school cost him the sight in his left eye, and he could never recapture the form that made him a 25-point-a-game scorer the year before.

“I missed a whole year of school with patches on my eyes,” he recalls. “Guys used to laugh at me because I’d walk around, bouncing my little Voit basketball all over the place. They’d say, ‘Whatta you think you’re going to do with that basketball? You think you’re gonna be a player or something?’ Well, I’m looking forward to going back there as coach of the Detroit Pistons.”

By the time he was 23 years old, Vitale was coaching at Garfield (N.J.) Junior High School, and later he spent seven seasons at East Rutherford High, coaching the school to two state championships before joining the Rutgers staff.

But it was in Detroit that his fertile mind and endless capacity for work carried him to the goal he dreamed of since a child. A series of gimmicks first caught the attention of the public. He opened each season by starting the Titans’ first practice at one minute past midnight—the earliest possible moment under NCAA rules. He promoted “Hoop Hysteria,” 24 straight hours of basketball in the school’s gym. When he discovered [Detroit Tigers’ ace pitcher] Mark Fidrych hadn’t attended college, he suggested he might offer “The Bird” a basketballscholarship. When the Titans were introduced at home games, the lights were dimmed and a spotlight trained on a tissue paper hoop as the players, one by one, burst through.

It was all so hokey. But it worked.

It worked so well that Vitale’s Titans drew 9,105 for their home opener last season against Adrian; by comparison, the Pistons could lure just 4,745 downtown for their game against the Indiana Pacers.

Though Vitale doesn’t exactly fit the popular image of a pro basketball coach—6-foot-5, 230 pounds, with long years of experience in the big leagues—the Pistons could no longer ignore the promotional abilities of the man who likes to refer to himself as a “one-eyed, bald-headed Italian.” It seemed Vitale and his ideas were everywhere.

He suggested U-D play Michigan in the Silverdome, an idea the Wolverines scoffed at—before contracting to play Notre Dame at the same site. He was a color commentator for Channel 2 on a series of college basketball games last winter and still does twice-daily sports shows on radio station WRIF.

In 1977, when the Titans were in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, for the NCAA tournament, Vitale ordered Mike Brunker to load up with postcards. “I want you to buy the 10 biggest postcards you can find all about Baton Rouge,” Vitale told Brunker, who was his assistant at U-D and made the move with him to the Pistons. “Send them to our top 10 prospects. Tell them how great it is down here. Tell them we’d like them to be with us next year.”

****

Doubters have said the gimmicks and enthusiasm he used to motivate his college players won’t work in the pros. But Vitale says they will. “If they can’t bust their butts for a couple of hours a day, giving an honest effort, we’ll find people who can.”

In recent years, the Pistons have acquired the reputation of a team that is less competitive on the court than on the bench. At times, there’s been an open rebellion against the coach. Vitale, like those who preceded him in the job, feels he is a superior handler of people, capable of avoiding most of those situations and coping with the others. “If you give respect, you’ll get respect back,” is one of his mottos. But the unofficial alumni club of former NBA coaches can tell him that’s not necessarily so in this league.

Ironically, those who doubt Vitale’s ability to cope with the pressures of coaching and motivating a dozen high-salaried and temperamental athletes are generally people who don’t know him. Vitale and his enthusiasms make immediate impressions on those who meet him. And most of them become Vitale converts.

Bubbles Hawkins is just one among them. The guard from Detroit’s Pershing High, who was cut by the New Jersey Nets last season, showed up at the Piston tryout camp in midsummer, knowing almost nothing about the new coach. By the time, the three-day camp ended, Hawkins was a believer. “The other pro coaches I’ve played for haven’t ever tried to motivate,” says the 24-year-old, who played college ball at Illinois State. “He’s a hard worker and a motivator . . . He’s an honest guy. When you’re not producing, he’ll tell you from his heart.

“He pulled me over one day and had a talk with me. I need somebody to pat me on the back and give me some confidence rather than pushing me away. I’m kind of a sensitive guy and, to tell the truth, I need somebody like that.”

It appears that the Pistons do, too. Maybe Vitale is just the right man to do it.

[Dick Vitale lasted 94 games as head coach of the Detroit Pistons. Vitale lost 60 of them before he “got the Ziggy.” In this excellent piece, published on November 9, 1979 in the Detroit Free Press, sports columnist Jim Hawkins captures Vitale’s firing as Pistons’ coach. Here are the details.]

It was 9:30 Thursday morning when Dick Vitale’s secretary, Madelon Hazy, phoned him at home to say Pistons’ owner Bill Davidson was in the neighborhood and would be stopping by later in the day.

“What’s this about?” Dick wanted to know.

“I have no idea,” Madelon replied.

Vitale had been awake all night, replaying the Pistons’ lackluster 115-107 loss to Atlanta in his mind and second-guessing himself for letting the game get away. So he assumed his boss wanted to discuss the progress of the team or possibly give him a little pep talk.

He was in for a surprise. When Davidson arrived some 75 minutes later, he got straight to the point. “I think it’s best,” Davidson declared, “for you and for everyone involved, if you step down as coach.”

For the next several minutes, Dick Vitale cried.

For more than a year, ever since he took the job that once seemed like a dream come true, Vitale had been telling Davidson that he, Dick Vitale, was to blame because the Pistons weren’t winning. And Davidson kept assuring Dick, it wasn’t his fault.

Thursday, the owner finally decided to believe his coach.

“I brought this on myself,” Vitale admitted after he had been publicly defrocked. “Every time I called him, I was down. But how else can you be when you’re losing? I talked to him almost every day. But all I did was moan. I’d say, ‘We’re not doing this,’ and ‘We’re not doing that.’ I think that played a great part in his decision. I think he just got tired of hearing it.”

Officially, co-owner and legal counsel Oscar Feldman declared: “Dick Vitale and the Detroit Pistons have mutually agreed to relieve Dick of his responsibilities as coach.” To some, that may sound as if Vitale retired. But don’t believe it. The man was flat-out fired, pure and simple.

Feldman tried to make it sound as though, by dumping Vitale, they were actually doing the guy a favor. He spoke of Dick’s intensity and his enthusiasm and his inability to accept defeat as though those characteristics were negative attributes—ignoring the fact that those were the very things that convinced the Pistons to hire Vitale in the first place, 19 months ago.

The truth is, Vitale was fired because the Pistons, in last place with a 4-8 record, have not performed like the basketball team that Davidson and Feldman believe them to be. Perhaps more significantly, he was fired because he did not hesitate to let Davidson and Feldman know, in no uncertain terms, when he did not agree with the decisions they made—most recently a controversial decision to release John Shumate rather than risk spending another $250,000 on an athlete whose health was uncertain, at least, in the opinion of some.

In fact, Vitale was on the verge of quitting on his own accord when Shumate was cut 10 days ago—one week after Feldman had assured the player he had nothing to worry about.

After axing Vitale over coffee in his own home, Davidson didn’t even bother to show up at Thursday afternoon’s press conference at the Silverdome to ceremoniously announce the sacking. Feldman, who did the dirty work, said the Pistons’ principal owner had a prior commitment. Of course, he had already seen Vitale cry.

Dick promised his wife that he wouldn’t break down and bawl in front of the press, and somehow he kept his composure. But at times, it was a struggle.

While Feldman acted as executioner, Vitale paced back and forth alongside him, head down, eyes red, his hands buried deep in the pockets of his pants. He stared out the window into the empty press box. Impatiently, he rocked back and forth on his heels, all the while staring at the floor. However, when it was his turn to speak, he was the same ‘ol Dick Vitale.

He laughed about his plight, noting: “You guys aren’t going to have to put up with me any longer.” He praised the press for making him a celebrity in town and bemoaned the fact that maître d’s may no longer invite him to advance immediately to the front of the line every time he enters a restaurant.

To please his employers, who will continue to pay his $100,000-a-year salary while they try to find another place for him in the organization, Vitale mouthed the party line, announcing he had, indeed, resigned. He praised the talent on the team and predicted the Pistons are still capable of winning often enough to advance into the playoffs.

He blamed himself, declaring: ”I might have been my biggest downfall.” And he admitted: “A coach’s duty is to get the maximum out of his talent.” To hear Vitale tell it, he let down just about everybody in town.

It was a sad sight.

Friday evening, the Pistons—with Vitale’s buddy and former assistant Richie Adubato, temporarily at the helm—will take on the Philadelphia 76ers at the Silverdome. Vitale’s wife, Lorraine, already has sold more than 400 tickets for the game as part of a PTA fundraiser at their two daughters’ school. For weeks, the girls have been looking forward to showing off their daddy to their friends.

“Now, I’m not going to be here Friday night,” sighed Vitale. “And I don’t think my daughters are going to be here either.”