[In today’s increasingly position-less NBA, it can be hard for younger fans to recognize just how rigid the positions guard, forward, and center used to be across basketball. Or, how these three positions evolved over the years to help the game progress to the versatile Lebron, Luka, and Tatum.

In this article, published in the January/February 2000 issue of the magazine Hangtimes, Chris Ekstrand chronicles the rise of the power forward. Ekstrand, then a staff writer for Hoop and now a long-time NBA consultant, does a nice job with this story and his sourcing is first rate. Definitely worth the read.]

****

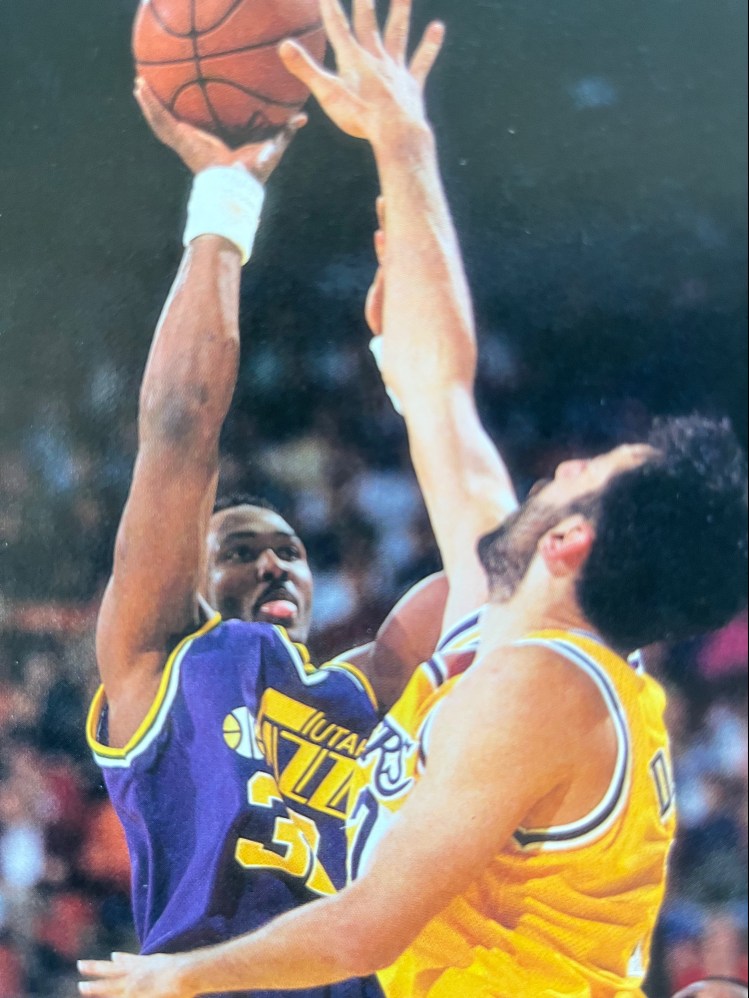

Take one look at Karl Malone’s sculpted 6-9, 260-pound frame, Watch him grab rebounds in traffic and muscle up shots close to the basket, and it’s easy to see why he is accepted as today’s prototype at the power forward position. But watch Malone sink 20-foot jumpers, whip pinpoint passes to cutting teammates, and fill the lane on the fastbreak, and it’s equally apparent that the definition of what makes a power forward is as varied as the sensational athletes who collectively represent the history of the position.

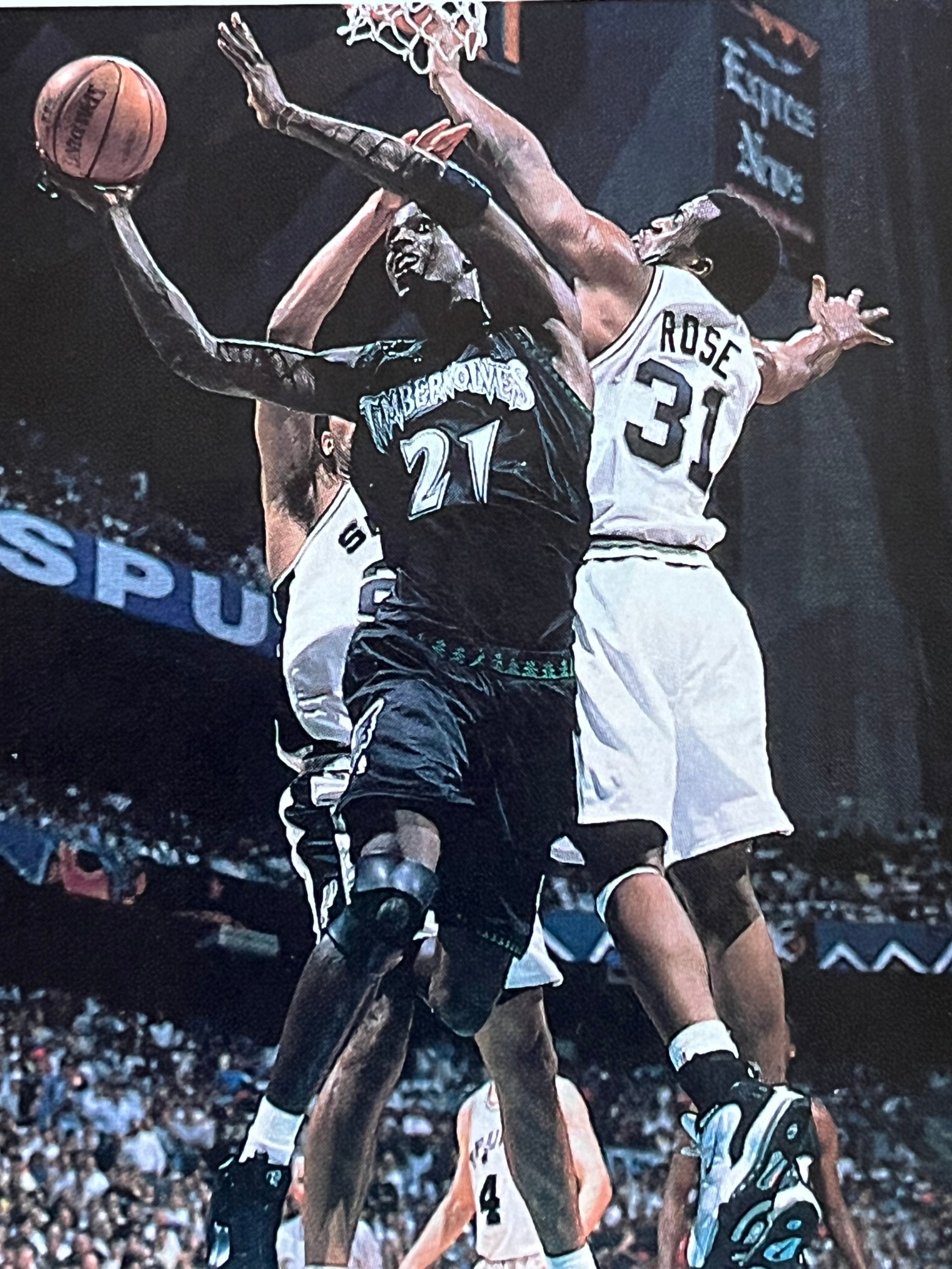

Now Kevin Garnett, a 23-year-old seven-footer with exceptional athletic abilities, stands poised to add yet another layer to the rich history of the power forward, which includes many years before the term even came into being. Although he’s nowhere near the imposing, muscular specimen that is Malone, Garnett terrorizes NBA frontcourt players with his athleticism, flying in from unimaginable angles for slam dunks, living above the rim at both ends of the court.

Watch Garnett for a while, and it’s clear he and contemporaries like Tim Duncan, Chris Webber, Antonio McDyess, and Antoine Walker will add their own unique characteristics to the storied history at the position, no matter what it’s called.

****

The term “power forward” is a relative newcomer to the NBA’s lexicon. While Hall of Famers like Bob Pettit, Dolph Schayes, and Vern Mikkelsen were big forwards who played with much of the vigor and physicality that undoubtedly make up part of the job description, they were not called power forwards during their careers in the 1950s and 1960s. Many of the best players from that era, in fact, have little use for the term.

“It means absolutely, positively nothing, other than someone came up with that title,” said Thomas “Satch” Sanders, the NBA’s Vice President of Player Programs, who filled the role of defensive forward for the Boston Celtics when the team won eight NBA titles in nine seasons from 1961 through 1969.

“That’s really only a recent term,” said Schayes, who scored 19,247 points and grabbed more than 11,000 rebounds from 1948 to 1963 for the Syracuse Nationals. “We didn’t use that term in those days. The younger coaches came in and categorized everything. It’s only since then that they started labeling players by position: 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5.”

Whether the term is used or not, one thing is certain: There are as many different definitions of what a power forward is as there are power forwards. Pettit was different from Schayes, Dave DeBusschere was different from Gus Johnson, Spencer Haywood was different from Buck Williams, Charles Oakley, and Kevin McHale, and Elvin Hayes was different from Charles Barkley, Kevin Willis, Shawn Kemp, and Dennis Rodman.

Garnett? There’s nobody like him.

And the prototype, Karl Malone? While most accept that among active players, he is the ultimate at the position, the term “prototype” implies similar versions on the way, a dubious prediction of best.

“The connotation of power forward in the past was a guy that wasn’t really offensive-minded, that rebounded, played tough defense, and took care of all the physical problems,” said Paul Silas, head coach of the Charlotte Hornets, who grabbed 12,357 rebounds during an exemplary 16-year NBA career that included three NBA championships.

“If a player got into it with another player, he came to the rescue. Nowadays, a power forward is more of a shooter, more of an athlete, and not as much of an enforcer as they were at one time.”

Trying to retrofit the great players of the past into a category that didn’t exist back then is only part of the problem. While everyone seems comfortable referring to legendary greats Malone or Hayes at power forwards, there are dozens of players who, for one reason or another, don’t fit neatly into that package.

Dan Issel, a great center for the Denver Nuggets in the ABA and NBA, played power forward for four seasons early in his ABA career with the Kentucky Colonels due to the presence of 7-2 Artis Gilmore in the pivot. Nate Thurmond, one of the greatest centers in NBA history, began his NBA career in 1963 as a 6-11, 235-pound power forward with the San Francisco Warriors, who had a guy named Wilt Chamberlain playing center. The New York Knicks traded away Hall-of-Fame center Walt Bellamy in order to move undersized Willis Reed into the center spot. The Knicks went on to win two NBA titles with Reed in the middle.

In today’s NBA, Indiana’s Dale Davis, an impressive 6-11, 230-pounder, has played his entire career with the Pacers at power forward, since 7-4 Rik Smits was entrenched at center. Dave Cowens would probably have been a great power forward, but he played nearly his entire career at center. So who becomes a power forward has as much to do with circumstances as design.

“I don’t think anyone should be stereotyped at one position,” said DeBusschere, who many all-time greats tabbed as the player first referred to as a power forward. “We never used those terms when I started in the NBA. We never had a one guard or point guard either. You were either a guard, a forward, or a center. We never used numbers either. That didn’t come around until I quit playing.”

“In the old days, you had guards, forwards, and centers,” echoed NBA Director of Scouting Marty Blake, whose career as an NBA general manager and scout spans more than 45 years. “And that’s what you have today. The difference today is that you have more versatility because you have better athletes, not necessarily better players. These players will add their own touch, and it will be a little different than anything that has come before.”

While the semantical discussion about the term “power forward” has the potential to keep basketball experts arguing well into the next millennium, there is no denying that many of the players who offered their teams a physical presence, who rebounded, scored, and brought toughness to his job made an indelible mark on the NBA. And the importance of a player with power at forward cannot be overstated. With 29 teams in the NBA, only a fortunate few are able to get an elite center, so strength and toughness need to be present at one of the forward positions. At any given moment, the NBA rebounding leaders reflect the significance of the position. In recent weeks, seven of the top 10 rebounders in the league were power forwards.

****

Not every one of the great power forwards had the height and physique of a Karl Malone or Elvin Hayes. Charles Barkley, a shade under 6-6, will go down in history as one of the most unlikely power players of all time. With an indomitable will and the ability to carve out space for himself and get shots off against defenders a head taller, Barkley has rampaged his way through 16 NBA seasons. After suffering a season-ending injury on December 8, 1999, he retires from the NBA among the top 15 all-time in scoring and rebounding.

“My body was not meant to play the way I do,” Barkley once said. “I’m shorter than most of the guys who play up front in the NBA, so I’ve always known that someday it would take its toll, that my body would just give in to the pounding it took 82 nights during the regular season and during the playoffs. But that was OK. It was a sacrifice I had decided to make. I always knew I only had a certain amount of time in this game, and that the bumps, bruises, strains, and sprains could heal up when I was through.”

One of Barkley’s contemporaries was another unlikely looking chap, 6-10 Kevin McHale of the Boston Celtics. McHale would never be described as muscular, but he had extremely long arms and great hands, and as his career progressed, he developed what was arguably the most varied post-up game of all time. Using a series of head-and-shoulder fakes, up-and-down moves, and clever release points that made opposing big men shake their heads in disbelief, McHale was one of the most unstoppable low-post scorers in NBA history.

****

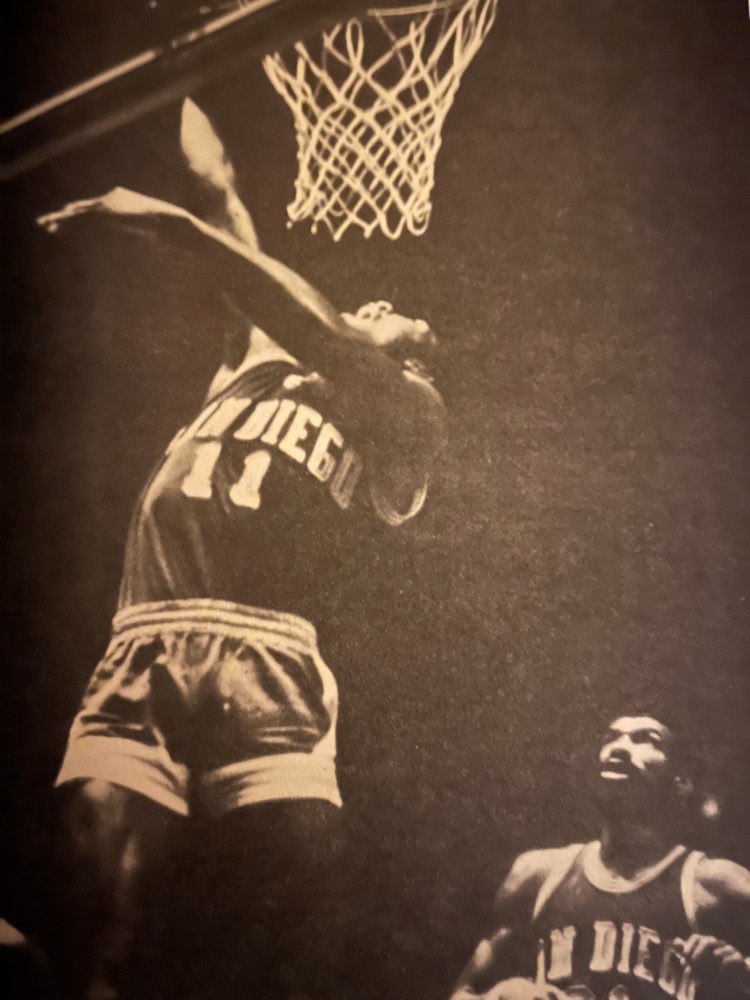

Before Barkley and McHale, there was Elvin Hayes. Like Malone, Hayes was a big-time player from a small town in Louisiana. He was already famous when he came into the NBA after having scored 39 points for the University of Houston in the game that ended UCLA’s 47-game win streak in January 1968. But as in that game against Lew Alcindor (later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), Hayes played center for the San Diego and Houston Rockets during his first four seasons in the league.

“What really gave me an advantage was that my first four years, I had to play center,” Hayes said. “I played against Russell, Wilt, Thurmond, Abdul-Jabbar, Bellamy. All of those guys were bigger than me. It made me develop shots and made me develop my quickness to elude these guys and achieve the objectives that I had on the court.”

In one of the most one-sided deals in NBA history, the Rockets traded Hayes to the Baltimore Bullets for scoring forward Jack Marin and future considerations. The trade meant Hayes would team with Wes Unseld, who had beaten him out for Rookie of the Year honors four years earlier. While Unseld took and dished out punishment in the pivot, Hayes exploited all his advantages over other power forwards and became known as the NBA’s best at the position. He led the Bullets to the 1978 NBA championship.

“Going to Baltimore gave me the opportunity to play with Wes Unseld and be put in the position where I could be the player that my talent and ability were designed for,” said Hayes, who is fourth in NBA history in rebounds (16,279), sixth in points (27,313), and second only to Abdul-Jabbar in minutes played (50,000).

“Most of the forwards at that time were 6-7, and I was 6-9 ½. That inch or inch and a half made a big difference. Guys like Bill Bridges and Paul Silas had size, but they didn’t have the quickness, so I could elude them. Bob McAdoo had height and quickness, but not the strength to contain me. So this [moving to forward] took my game and elevated it to another level.”

Hayes, who said he enjoys watching Malone and Duncan, was ahead of his time, a man of immense physical strength who also had quickness and jumping ability. His turn-around jump shot was nearly as unstoppable as an Abdul-Jabbar sky hook. A keen observer of today’s NBA game, Hayes praised Malone’s ability to score, inside and outside, and use both his strength and agility to dominate his opponents.

“Many of the big forwards today do not have the ability to score and make that position a dominant position,” Hayes said. “Karl, that’s like watching myself at times.”

****

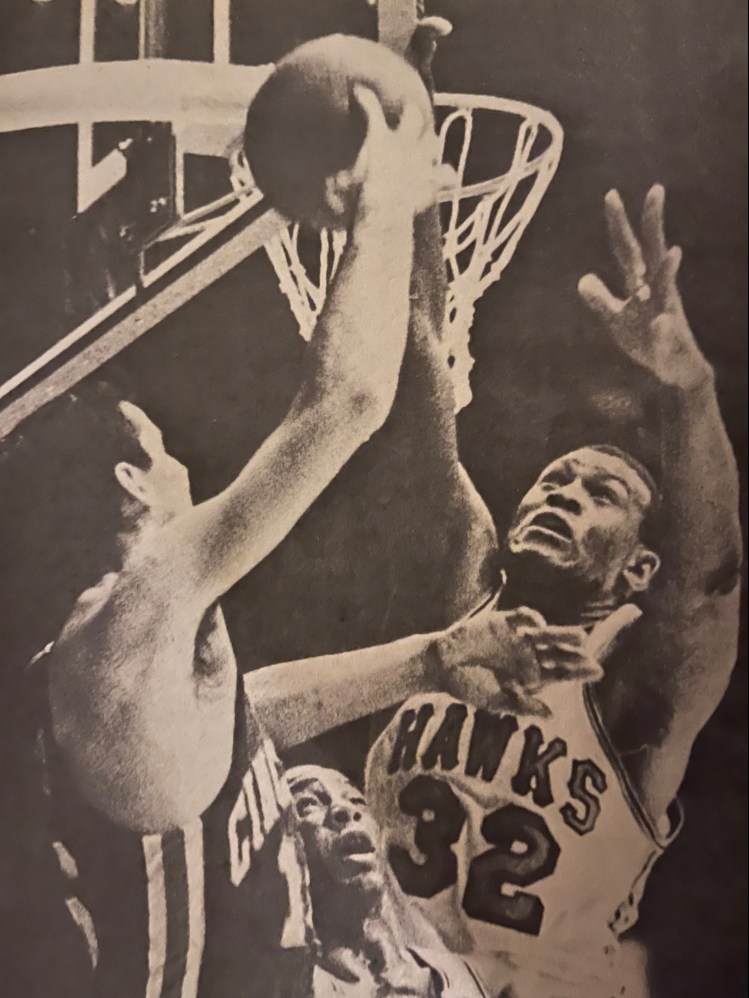

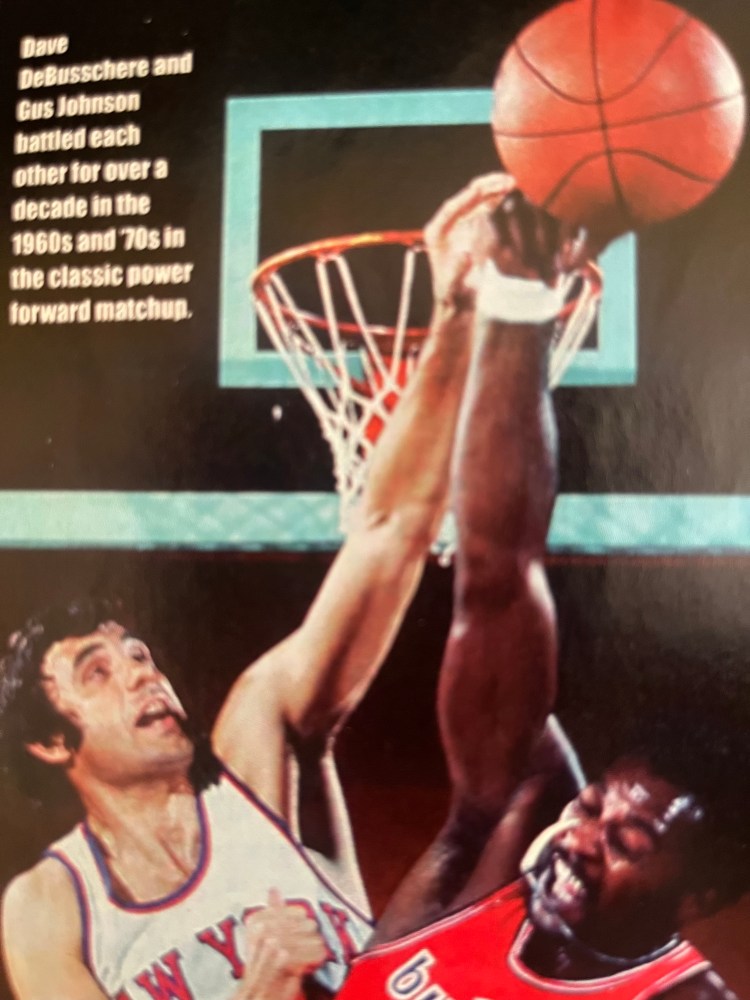

Many all-time greats believe the term “power forward” was invented by New York sportswriters looking for a way to describe Dave DeBusschere, who played every minute on the court with reckless abandon. DeBusschere played against physical, powerful men like Silas, Jerry Lucas, and Bill Bridges during his years in the league from 1962 to 1974. But there was something special about his fierce battles with the late Gus Johnson of the Baltimore Bullets. The Knicks and Bullets were two of the best teams in the East in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

“The matchups were all classics with Wes Unseld and Willis, Earl Monroe and Walt Frazier, Kevin Loughery and Dick Barnett, and, of course, Gus Johnson and Dave DeBusschere. That was maybe the classic matchup of all time,” said Marin, the Bullets’ scoring small forward who played his part in the duel, going against Bill Bradley.

For those lucky enough to witness it, Johnson vs. DeBusschere was a purist’s delight. Johnson was in muscular leaper who played all-out all the time, the type of player who could embarrass a defender with a slam dunk that would be talked about for weeks afterward. DeBusschere was not the athlete Johnson was, but was a better shooter and left every ounce of effort on the floor every night.

“I never liked to play against Gus, and the main reason was that I knew I would come away pretty beat up, usually black and blue in a lot of places,” DeBusschere said with a laugh. “Gus and I had a lot of respect for each other, I think that’s the best way to put it. We played very hard against each other. I really had to, otherwise he would just bowl you over. He was one of the stronger guys I’ve ever seen. In his prime, he was the epitome of the tough, strong guy, really quick, and he could play defense.”

****

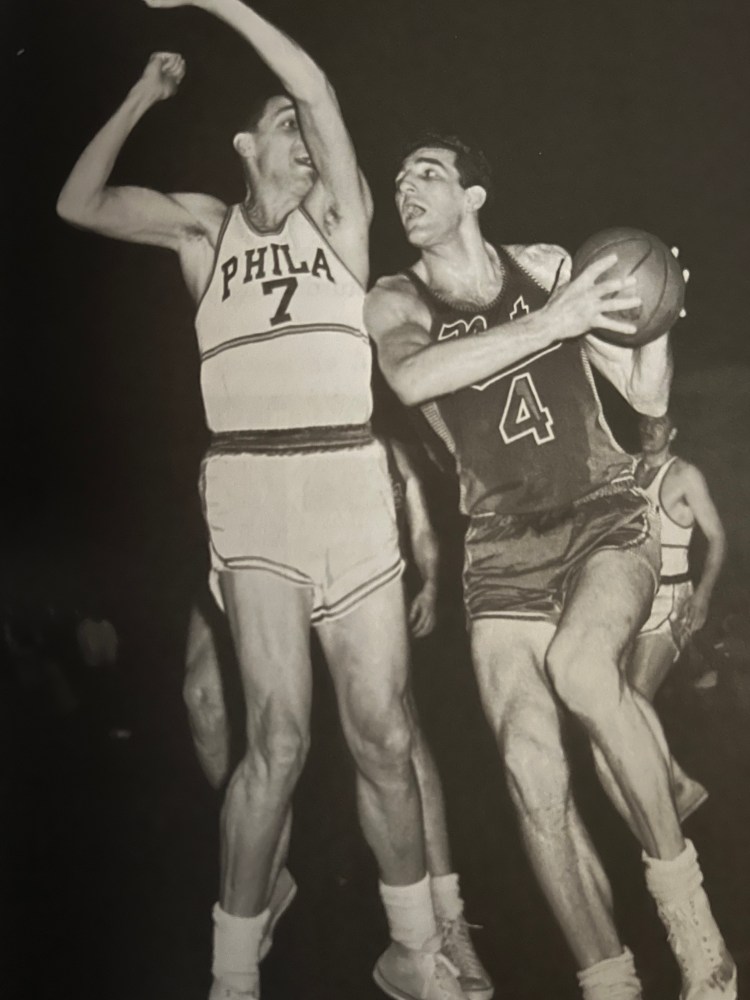

Although nobody used the term “power forward” in the 1960s, the men who embodied the position in those days were tough, rugged individuals. Vern Mikkelsen of the Minneapolis Lakers was part of what many regard as the greatest frontcourt in NBA history, teaming with center George Mikan and quick forward Jim Pollard. Together, the Hall of Fame trio won four NBA titles, including three straight from 1952 through 1954. While Mikkelsen complemented the team’s primary scoring force in Mikan, Bob Pettit of St. Louis and Schayes of Syracuse were always the leading scorers for their teams.

Schayes was already a three-time All-NBA first team forward when Pettit came into the league in 1954. Schayes was a terrific outside shooter who also got his share of points around the basket by employing nonstop hustle and desire. Because Schayes was expected to carry the scoring load for Syracuse, he was rarely assigned to guard Pettit, the Hawks’ scoring leader.

“Bob was a great scorer and great rebounder,” Schayes said. “He would be considered a power forward, but he wasn’t a defensive ace. I was aggressive, but I wasn’t a great defensive player, I guarded Paul Arizin once, and I think he had 30 points in one half.”

Pettit and Schayes were innovators, able to play away from the basket and score. Previously, that job had been left to guards and quicker, smaller forwards. Rugged forwards like Boston’s “Jungle Jim” Loscutoff, were expected to be physical and hold down the scoring forwards. At 6-9 and 215 pounds, Pettit was different.

“Pettit made himself into a great player,” said Blake, who was the general manager of the Hawks in St. Louis when the franchise captured the NBA championship in 1958. “He scored 19 of our last 21 points and had 50 points when we won the championship in the sixth game against Boston.

“Pettit liked to watch the rookies as they came into the league. He would see them, then pick up something from their games and add it to his game. He refined his game every year. Now I see Karl Malone doing the same thing.”

As Garnett and his contemporaries carry the banner for power forwards into the next century, they have a role model who is still around to show them how it’s done. “The way Karl plays basketball is the way everyone should play it,” said Utah coach Jerry Sloan. “He scores points not to draw attention to himself, but to get baskets and help us win. He works as hard as anybody I’ve ever been around, on and off the court. To me, that’s what playing should be. That’s what I admire.”