[The 1990s certainly brought a surge in the NBA power forward. The decade also brought a whole lot more swing to those mostly small forwards referred to as ‘swingmen.” They glide up and down the floor and, when called upon, have the ball skills and athletic ability to play just about any position. Here to tell the story of these NBA “rubbermen” is writer L. Jon Wertheim. His story appeared in the April 1994 issue of the magazine Rip City.]

****

Basketball purists, take heed. A legion of rebellious players, bored with typecasting by position, has prompted an era of versatility in the good ol’ National Basketball Association. They are known simply as the swingmen.

In the tradition of Elgin Baylor, Dr. J, and Michael Jordan, these contemporary rubbermen thrive any place on the court. Long gone are the days when NBA guards and forwards stood idly by while plodding big men pursued their predictable agendas in the paint. Sure, legend George Mikan, who epitomized the hulking center, had his merits. But his limitations were so great that were Mikan in uniform today, he would be little more than a begoggled Paul Mokeski.

In today’s quick-paced NBA, these stiff behemoths in the post have gone the way of the set shot. Replacing them are sleeker and shinier showroom models who slide effortlessly into three—even four—positions.

The Sch-WINGGGman, as [comic movie characters] Wayne and Garth might say, leaves less versatile counterparts crying, “We’re not worthy.” And, to be frank, they’re not.

So, what exactly defines a swingman? As the name suggests, a swingman is that rare player who, literally, can swing among several positions. Usually he is a large guard or small forward by nature, but because of well-honed skills, his position ultimately defies description. “The player of the 90s is in no way one-dimensional,” says Indiana Pacers general manager Donnie Walsh. “The swingman is a valuable player for any team to have.

“Take a player like [6-10] Cliff Robinson. He’s not really a power forward because he’s too quick. But he’s not really a small forward or a big guard because he’s too big and will shoot right over an opposing player. So what is he? I’ll tell you what he is—a darn good player!”

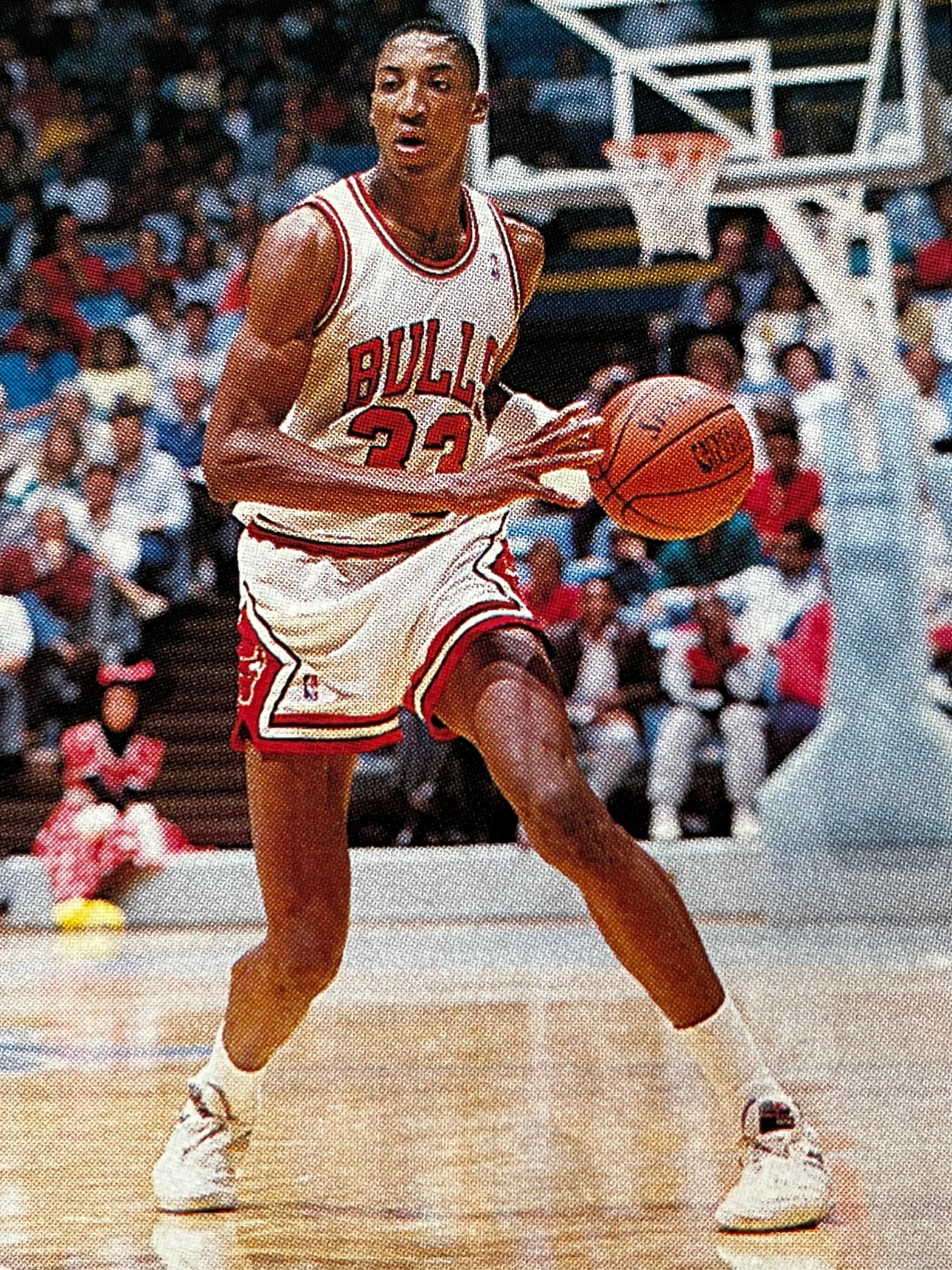

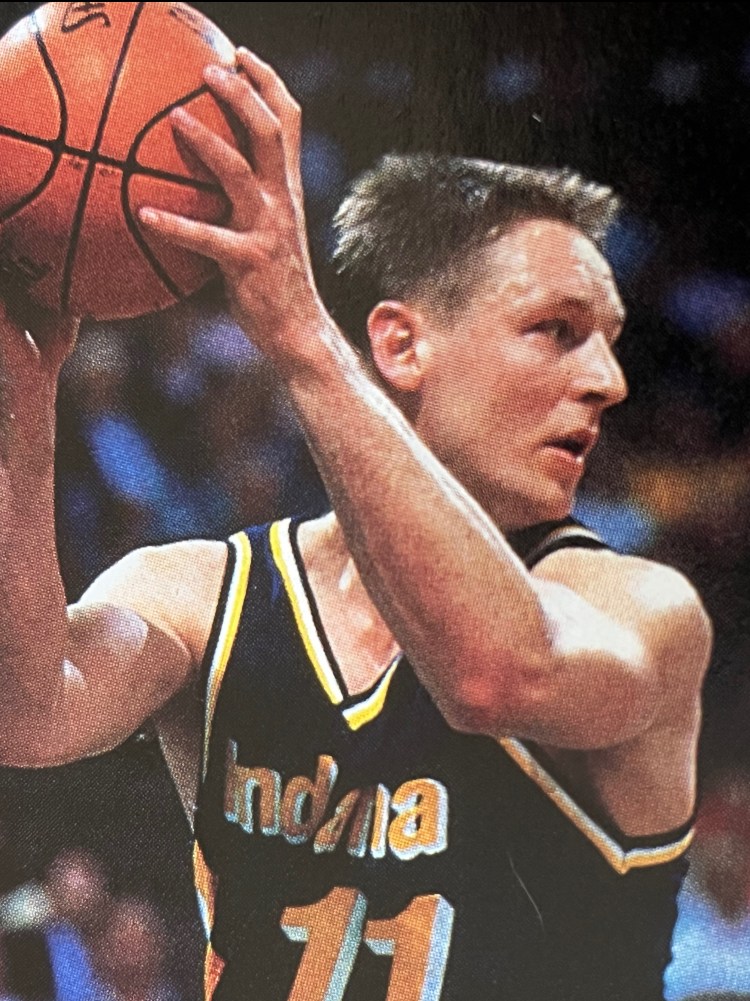

The era of multi-dimensional swingman stars like Portland’s Clifford Robinson, Chicago’s Scottie Pippen, Golden State’s Chris Webber, and Seattle’s Detlef Schrempf is not an overnight phenomena. Categorizing players strictly by height began to wane in the early 1980s, when Magic Johnson proved that standing 6-9 was no longer an excuse for dribbling as sloppily as a baby with a milk bottle. Shortly thereafter, swingmen in the mold of Bernard King, Dominique Wilkins, Paul Pressey, and Jerome Kersey trickled into the league.

Today, every team seems to have one of these jock-of-all-trades—or is trying desperately to acquire one. Squads such as the Dallas Mavericks, with Jimmy Jackson and Jamal Mashburn, have two.

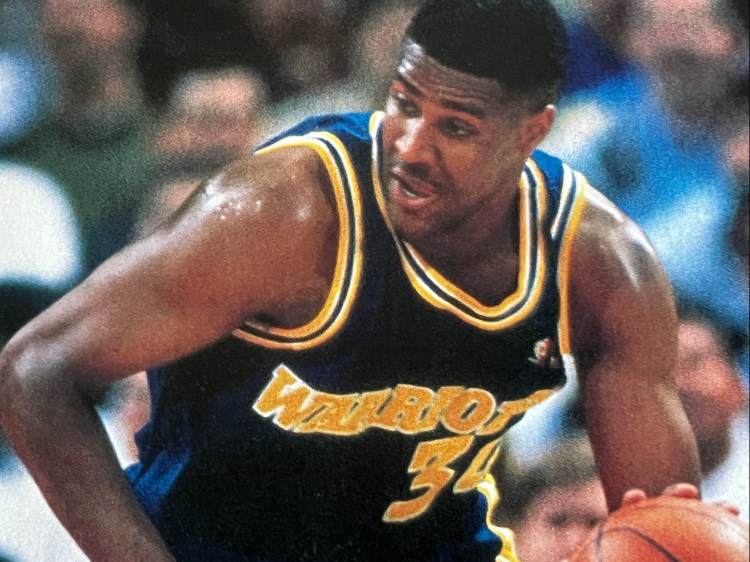

And then there are the Warriors. Don Nelson, Golden State’s coach and who never will be accused of being conventional, often has three swingmen on the floor at once. Billy Owens is a beefy forward with a sweet outside touch and superb passing skills. Latrell Sprewell has been likened to Scottie Pippen with less striking facial features. And the Warriors’ rookie center, Chris Webber, can dribble coast-to-coast as well as any guard. Fans will recall that it was Webber who dribbled the ball downcourt before calling that infamous timeout during last season’s NCAA Final.

Yes, but it is the same Chris Webber who, three weeks into his rookie NBA season, took an outlet pass at halfcourt, dribbled, took the ball behind his back, and then jammed over Charles Barkley. And yes, he also picked up the foul and knocked down the free throw.

The list of players who are as comfortable shooting from the arena parking lot as they are bucking backsides with beefy seven-footers increases every college draft. European-born players, such as Schrempf, Boston Celtics forward Dino Radja, and the Bulls’ Tony Kukoc, exemplify the trend.

When he was traded from the Pacers to the Sonics last fall, Shrempf immediately transformed Seattle from a pack of athletic enigmas into serious contenders. Shrempf can score, but since every other Sonics can too, he doesn’t always get the call. His more treasured skills are of the less glamorous variety: rebounding, assists, defensive flexibility, and even, at times, handling the ball.

Schrempf’s game is suited perfectly to Sonics coach George Karl, who captains one of the least traditional ships in the league. An enormous fan of the European game, Karl is as opposed to convention as Schrempf’s hair is to style. As a result, the Sonics center, Sam Perkins, shoots three-pointers, six players average in double-figures, and Schrempf never has been more appreciated. “Detlef is able to do so much and has such great instincts,” says Karl, “that it makes us a better team.”

In Chicago, no one can traverse the rarefied air on which Michael once walked. But both Kukoc, a Jordanesque demigod in Europe, and Pippen, the 1994 NBA All-Star Game MVP, acquit themselves quite well.

Though he stands 6-11, Kukoc handles the ball with panache. He also has a knack for nailing game-winning baskets from virtually any spot on the court. Pippen, who no longer toils in Jordan’s immense shadow, perhaps has become the consummate swingman. Not only is he a tidy package of offensive versatility, but on defense, too, he serves as many functions as a Swiss Army knife. He has been known to help double-team centers in the low post, but also was seen guarding Suns whippet point guard Kevin Johnson at times during last season’s NBA Finals.

“It’s easier to be a swingman from a defensive standpoint,” says Jerry West, general manager of the Lakers. “There are a number of players who can guard any of the three or even four positions, but Pippen really does it all. He’s the ultimate swingman defensively, and he is as comfortable bringing the basketball upcourt as he is scoring in the low post.”

Not all players who defy classification by position, however, are destined for success as NBA swingmen. NBA coaches and general managers know all too well that a fine line exists between the swingman and the “tweener.”

The tweener is stuck between positions and never finds his NBA niche. A classic example is Bo Kimble, a lottery pick in 1990 who is no longer in the league. At 6-5, Kimble was too small to continue to play his natural position in college—power forward—when he arrived in the NBA. Kimble’s shaky shooting eye and unsure handle made him ill-equipped to play guard.

As a result, Kimble’s most significant basketball achievement since leading Loyola Marymount to an emotional NCAA tournament run in 1990 has been a bit part in the hoop movie Heaven is a Playground.

“What separates a successful swingman from a player who cannot find a position is skills,” says the Pacers’ Walsh. “Terry Porter [in Portland] is a good example of a guy who was too small to continue playing forward in the pros, but because he had the skills to play guard, he did well in the NBA.”

The proof, according to Brad, Greenberg, Blazers’ vice president of player personnel, is in the proverbial pudding. “If you are a tweener, you are not quite as adept at playing two positions,” he says. “You are stuck in the middle. A swingman can do it all.”