[The Philadelphia 76ers have featured some fantastic backcourts through the years. One that had some classic moments in the 1990s, but which hasn’t been remembered up to the present as fondly as it deserves, is the backcourt duo of the playmaker Johnny Dawkins, the quicksilver southpaw from Duke, and his steady, hot-shooting partner Hersey Hawkins. They lasted about five seasons with the Sixers, and this article, published in the May 1990 issue of the magazine Philly Sport, takes an early look at the pairing of what promised to be a dynamic duo. At the keyboard is Richard O’Connor, a Philadelphia favorite.]

****

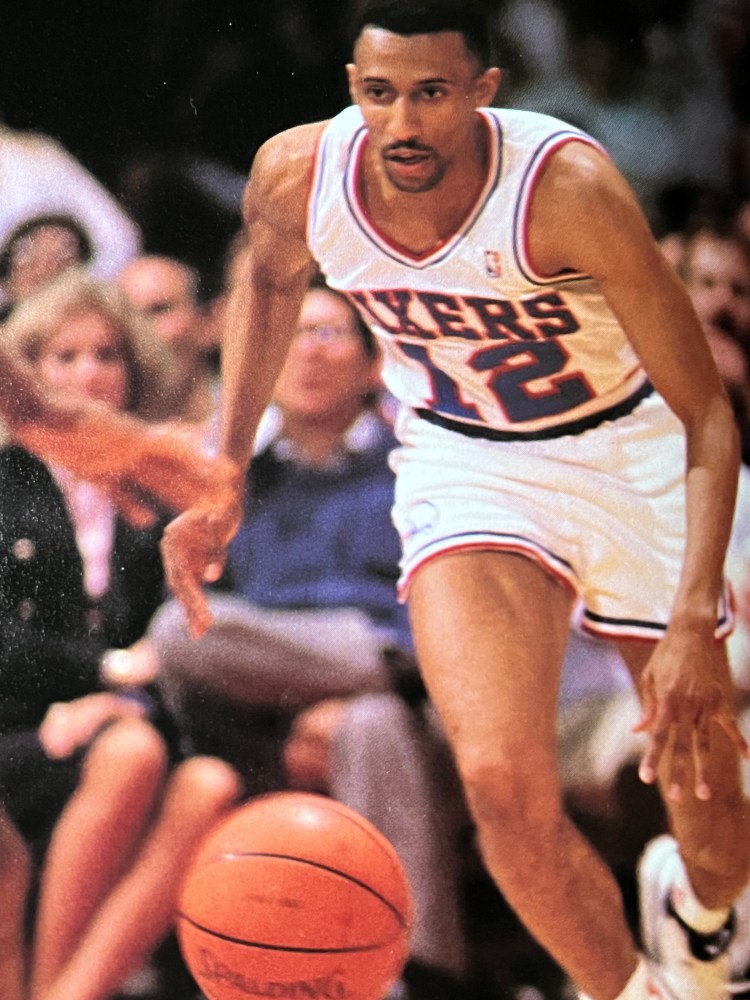

Johnny Dawkins, who is being closely defended by New Jersey Nets guard Lester Connor, brings the ball upcourt at the Meadowlands. As he nears halfcourt, his eyes scan his teammates, moving into their offensive positions. Computations immediately whir in his head. He signals a play and accelerates to the basket.

Meanwhile, Hersey Hawkins moves from the right side of the court to the left. He swims around the vicinity of the basket, running Nets defender Dennis Hopson into Charles Barkley and Rick Mahorn screens. Dawkins, now at the top of the key, shakes and bakes, blows by Connor, and heads down the lane.

Suddenly, Hopson slides over to block his path. For a second, it looks as if Dawkins will run over Hopson and get called for a charge. But at the last possible moment, Dawkins applies the brakes, and in one fluid motion, flicks the ball out to Hawkins, who is standing, unguarded, just outside the three-point line. Hawkins catches the pass, squares toward the basket, rises. The ball leaves his fingertips and a second later whips through the center of the basket with such force and precision that the bottom of the net flounces up and wraps itself around the rim.

****

Great NBA backcourts develop only when talent and personality mesh. Think of Andrew Toney and Maurice Cheeks, who were as different as Felix Unger and Oscar Madison. Cheeks was a shy, quiet man whose game was based on intelligence and control; Toney’s playing style was founded on instinct and recklessness. Yet, the two worked with more harmony than the Gershwins; and they succeeded—like Hersey Hawkins and Johnny Dawkins are doing today. The only difference is, the current Sixers backcourt has a style very different from their much-admired predecessors.

Just last August, when the Sixers announced they had traded Cheeks for Dawkins (and Jay Vincent), the city papers responded with howling, bloody rage. “The Sixers are losing the soul of the team,” cried the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Jere Longman, adding that it “was a trade fiasco that could rival the Jeff Ruland debacle in terms of retarding the club’s progress.” Later in the story, he theorized: “Dawkins’s history does not suggest that he will have the Sixers swimming upstream anytime soon. At the moment, the team appears merely to be treading water.”

Why was the press so down on Dawkins? Was it because he wasn’t a so-called “true” point guard? Was it because he was a supposed long-range shooter who thought shoot first and pass second? Or was it because the skeptics doubted he could team up with Hersey Hawkins, a player who thought shoot first and shoot second?

“It was,” Dawkins says, “all of those things.”

It was also because Dawkins was considered damaged goods. Day after day, the papers harped on the fact that the previous Christmas, Dawkins had pulled a muscle in his left leg, applied ice on the back of his knee for too long, and wound up with a condition known as “drop foot”—a freak ailment of the peroneal nerve which causes a person to lose control of the foot. The press wondered if it was career-threatening. They pointed to Atlanta Falcons All-Pro running back William Andrews, who had suffered a similar injury a few years earlier. Despite intense rehabilitation, Andrews never played again.

Dawkins tried to tell the press that, first of all, he really was a point guard. Only his game was different from Cheeks’s: He was quicker, more of a penetrator, a better shooter. As for his injury—forget about it, he said, he was fine. Guarantee it. “The only person who wasn’t concerned about my health,” he says, “was me.”

At the same time, critics were jumping on Dawkins, they were also criticizing Hawkins. They said he had only a fair rookie season. They continually brought up his poor shooting percentage (.455) and his absolutely horrid 3-of-24 playoff performance against the Knicks. Some said he choked. Others said he proved, conclusively, that when his shot wasn’t falling, he was no better than an average player.

Indeed, the thought of Hawkins and Dawkins in the same backcourt did more than just confound the Philly papers. It drew big chuckles from a number of NBA coaches. Said one: “Those two have as much chance of working well together as Tai Babilonia would have skating with Gerald Ford.”

Such criticism failed to bother Sixers general manager John Nash, who orchestrated the deal. Nash said he had always liked Dawkins’ game and, at 26, he was seven years younger than Cheeks.

“We checked Johnny out, physically, and he got a clean bill of health,” Nash says. “We wanted a guy who could score and push the ball up the floor. Johnny has certainly exceeded our expectations. But more importantly, he’s proven to be a great kid who’s really added to the good chemistry this team possesses.”

Others have noticed. “Guards are very instrumental in creating the overall personality of the team,” says Dallas Mavericks personnel chief Rick Sund. “In the case of Hawkins and Dawkins, they seem to really enjoy playing together. And I think that enjoyment has carried over to the rest of the team.”

****

Hersey Hawkins, wearing a royal blue Nike sweatsuit, and Johnny Dawkins, dressed in jeans and a black Sixers shirt, are sitting in Friday’s on City Line Avenue, discussing their relationship. “We pretty much hit it off right from the beginning,” Hawkins says. He chuckles. “In fact, my wife and his are always kidding about how much alike we are.”

For one thing, the Sixers’ backcourt tandem have similar backgrounds. Both grew up in the inner-city—Dawkins in Washington, D.C., Hawkins in Chicago; both come from loving, hard-working families; both were quiet, unassuming kids, well-liked by their teachers, and both, of course, became addicted to basketball at an early age, though Dawkins’ talent was apparent earlier.

As a grade school player, Johnny Dawkins was the Mozart of the court. He possessed extraordinary speed and quickness. He handled and passed the ball like a little Globetrotter. He could drive to the basket and score over forwards, or he could launch graceful intercontinental missiles that hit the target with frightening regularity. His only weakness? He didn’t shoot enough. So his father bribed him. He offered Johnny a dime every time he scored a basket. Pretty soon little Johnny was scoring 10, 15 baskets a game. The deal was soon canceled.

Dawkins attended Mackin High, where he was All-Planet. He was recruited by almost every college in the country and ultimately chose Duke University over N.C. State and Notre Dame. “We always knew Johnny would be a player,” says Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski, “but we were concerned about how he’d cut it as a student. But John worked extremely hard to prove himself academically. I’m as proud of him as I am any player I’ve ever coached.”

The only problem Coach K had with Dawkins was—surprise—he didn’t shoot enough. “I had to beg him to shoot at times,” he recalls. “I really think his basic instinct is to be a passer.”

The San Antonio Spurs drafted Dawkins with the 10th pick in the 1986 draft. Though he played well for the Spurs, he was often injured. When Larry Brown took over the team last year, he confided to friends that he thought Dawkins wasn’t a true point guard. Brown thought he shot too much, instead of penetrating. As soon as he could, Brown unloaded him.

Hawkins, unlike Dawkins, was not a prodigy. In fact, as a grammar school player, the Hawk couldn’t shoot a lick. When he got to Chicago’s Westinghouse High, his coach Frank Lollino felt he was more effective inside. So Hawkins played center—which turned off most college recruiters.

Perhaps out of guilt, Lollino called then-Bradley University coach Dick Versace and invited him to watch his star athlete work out. Versace wasn’t interested, but Lollino was persistent. Finally, he agreed.

While Versace sat on a folding chair at halfcourt, Hawkins came out and began shooting set shots close to the basket. Bored, Versace whistled and cleaned his fingernails. Gradually, though, Hersey moved back until he was shooting bombs from 20 feet out. Nearly every one of them dropped through the net with an almost mechanical accuracy.

Versace offered Hawkins a scholarship on the spot, and he accepted, knowing he had nothing else. Four years later, Hawkins would become the third-leading scorer in the history of the NCAA (fourth, now, having been passed by La Salle’s Lionel Simmons) with 3,008 career points. The Los Angeles Clippers drafted him with the sixth pick in the 1988 draft, then traded him (along with a 1989 first-round pick) to the Sixers in exchange for Charles Smith.

****

Waiting for his order, Hawkins relates how when Dawkins first joined the team, he asked Sixers coach Jimmy Lynam if the two players could room together during the exhibition season. “I figured,” Hawkins says, “it would give us a chance to get to know each other. We talked about teammates, opponents, our own strengths and weaknesses. It was a very productive time for us.”

Did they spend most of their time talking about basketball?

Dawkins eyebrows rise. “The Hawk talk?” he cries. “Are you kidding? When I first met Hawk, he didn’t say a word. I’d be in the room talking to myself.”

Hawkins eyeballs him strangely. “I ain’t that quiet,” he says.

Dawkins smirks. “Oh, man! Who are you kidding?”

Hawkins frowns.

Dawkins stares at him and says, “Okay, I’ll say this: It takes the Hawk time to open up to you, but once he does—and he does now with me—there’s no stopping him. But really, he’s not a talker to a lot of people.”

“Maybe the reason I’m so quiet,” Hawkins says, “is because we’ve already got enough talkers on this team.”

Dawkins let out a whistle. “You ain’t kidding,” he says. “We’ve got the biggest collection of characters in the league.”

Hawkins chuckles. “Especially Rick and Charles,” he says. “When those two boys start attacking each other, it’s time to get your ass out of town. Man, they’re brutal.”

“Hey,” Dawkins says, “how’d you like to be at the point directing those guys?’

Hawkins shares his head vigorously. “No way, baby,” he says. “I could just see myself telling Charles to clear out, and he’d give me that nasty look of his and shout, ‘What’d you say?’”

It’s no secret that Barkley is always woofing. Talkin’ trash. Being defiant. Charles has been known to leave the huddle after the coach has given specific instructions to the point guard to run such-and-such a play, only to tell his teammates: “Screw him. Run this play.”

Cheeks knew how to deal with Barkley. He was older and wiser, a veteran. Some Sixers wondered how the low-key Johnny Dawkins would deal with Prince Charles. “Charles can be very strong-willed and stubborn on the floor,” says one Sixer. “He often does only what he wants to do. We didn’t know if Johnny could deal with Charles’ intimidating personality. But he has. It really helps that Charles has come to really respect his game.”

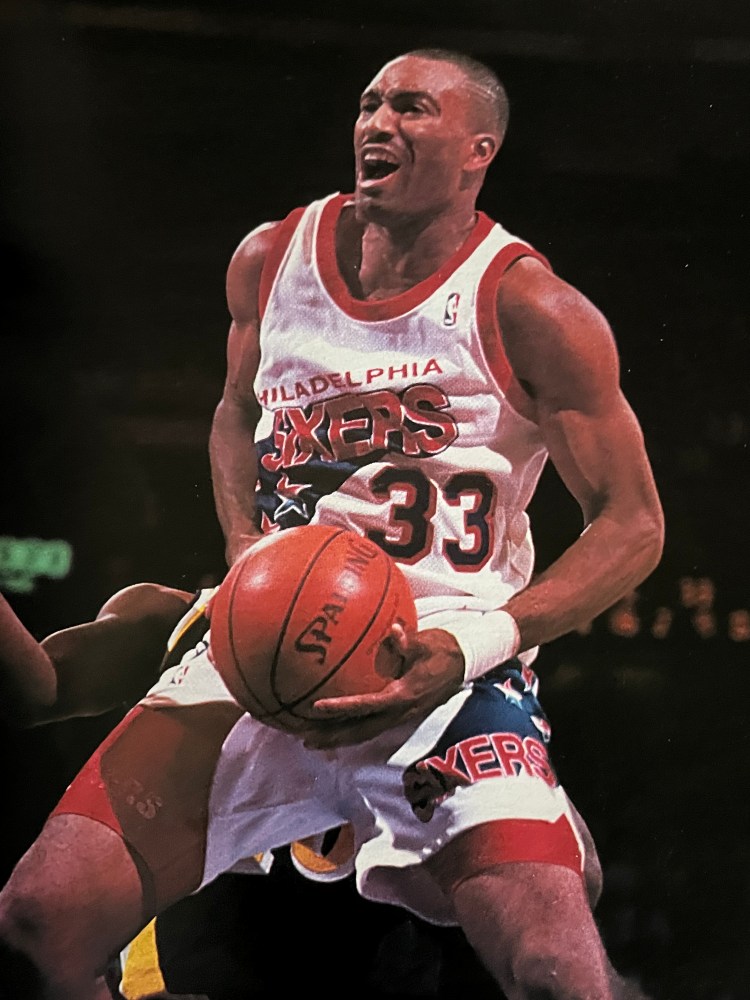

When the food arrives, Hawkins takes a bite out of his hamburger, while Dawkins discusses the contrast of playing with Hawkins as opposed to Alvin Robertson, his former San Antonio running mate. “Oh,” he says, “it’s completely different. One of the reasons I was happy to be traded to Philly was because of Hawk. To me, Hawk’s the consummate two guard. He’s got a scorer’s mentality. He’s always looking to get open and fire. Alvin, on the other hand, was both a one and two guard. He got a lot of steals. And I was quicker than hell. So I got a lot of easy baskets. It was great.”

The hamburger freezes at Hawkins’ lips. He slowly returns it to the plate and looks at Dawkins like Ralph Kramden would look at Ed Norton, a mixture of mock horror and affection. “Wait a second,” Hawkins says. “You saying I don’t get enough steals?”

Dawkins stares at him with surprise, he then breaks into hysterics.

“You know,” Hawkins continues. “I’m not that far behind you in steals.”

Dawkins rocks with laughter. “I know Hawk,” he says. “You’re getting there.”

Hawkins eyeballs Dawkins wearily, picks up his hamburger and resumes eating. It’s Hawkins’ turn. How is playing with Dawkins different from playing with Cheeks?

“Much different,” he says emphatically. “For one thing, Johnny’s a better overall athlete. He is a great penetrator and a great long-range shooter. Teams have to respect his jumper. They can’t double me as much as they used to, because now if they do, Johnny will burn them.” He shakes his head and admiration. “Man, he can shoot.”

Dawkins beams. “Why, thank you, Hawk.”

Hawkins feigns hurt. “I say that even if I don’t get as many steals as Robertson.”

Dawkins slaps the side of his face. “Oh brother!” he cries. “I’m never gonna hear the end of this.”

Hawkins shoots him a look that says: Damn right, you won’t.

Watching the two players interact, one gets the sense that they are as advertised: good guys with good attitudes who don’t indulge in petty jealousies or self-promotion. They know Barkley and Mahorn are the stars of the team, yet they’re willing to accept their roles and abide by them. What they seem to want more than anything else is to blend in, not only with each other, but with the entire team. As Rick Mahorn says, “It’s hard to find two better teammates.”

“You look around the league,” Dawkins says, “more and more teams have guards that are interchangeable. Look at Kevin Johnson and Jeff Hornacek at Phoenix. Isiah [Thomas] and Dumars at Detroit, Adams and Lever at Denver. And up until Rod Strickland was traded from New York, the Knicks were using him and Jackson at the same time. The point is, Hawk and I are progressing toward a more well-rounded duo.”

****

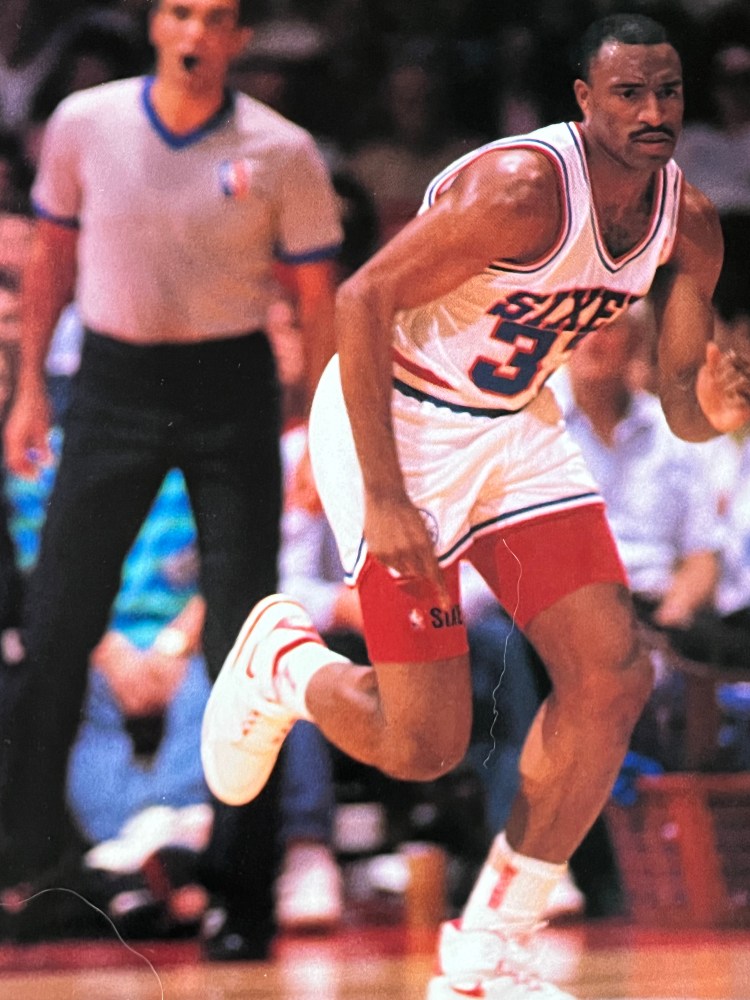

Back at the Meadowlands, the Sixers are set up in their halfcourt offense. Dawkins dribbles the ball at the top of the key, while Hawkins stands on the right wing. In the low post, Barkley jousts for position. He plants, his feet, spreads himself wide, and puts his big butt into Charles Shackleford, who must feel as if he is pinned beneath a car. Barkley raises his hand and signals for the ball, and Dawkins complies. Immediately Hawkins’ man splits and double-teams Barkley, who quickly kicks the ball back to Hawkins for an open jumper. Swish.

After the game, Barkley tells the press that “Hawkins is the key to our team. People give the credit to me and Rick, but Hersey is playing so well. He should have been named an all-star. When he hits the outside shot, it makes it so much easier for me. It’s so frustrating when I pass the basketball, and he doesn’t hit the shot.” A pause, then: “If he would be more aggressive, he could be among the two or three best guards in the league.”

Barkley has been known to grab Hawkins during the course of a game and tell him in no uncertain terms what he expects. It goes something like this:

Barkley (loudly): “Dammit, Hawk, shoot the damn ball!”

Hawkins (softly): “Okay, Charles.”

Barkley (even louder): You understand me?

Hawkins (even softer): Yes, Charles.

Barkley (grinning that crazed Jack Nicholson-like grin of his): “Good, Hawk. You’re gonna do well in this league.”

Most NBA observers agree that it’s Barkley who makes both Hawkins and Dawkins effective. “Charles,” says Jimmy Lynam, “is the most double-teamed player in the league. The beauty of both Hawkins and Dawkins is that they are both great outside shooters. Consequently, teams can’t cheat off either one of them, because if they do, one or the other of them will bury the jumper. On the other hand, when they do play Hawkins and Dawkins straight up, that opens up the middle for Charles—and Rick and G [Gminski]—to operate inside.”

The emergence of the duo’s perimeter prowess has turned around the inevitable comparisons to Cheeks and Toney from scornful to favorable ones. But it has also underscored significant differences.

“You can certainly make a comparison between Toney and Hawkins,” says Indiana Pacers scout Al Menendez. “Both are great outside shooters, though Toney was stronger and he could put it on the floor and go to the basket more. The big difference lies with Cheeks and Dawkins. Cheeks beat you with defense, whereas Dawkins beats you with offense.”

“The Toney-Cheeks and Hawkins-Dawkins comparison is certainly a legitimate one,” says Miami Heat assistant coach Dave Wohl. “The big difference is Dawkins. He gives the team great dimension, because he’s quicker, more of a penetrator, and a great outside shooter. But I’ve gotta say I’m surprised by how he’s adjusted his game to become more of a playmaker. When he was with San Antonio, he wasn’t under control, and maybe that’s because the Spurs played a wide-open passing game. With the Sixers, Dawkins is much more under control. He’s seeing the floor better, he’s giving it up quicker.”

Bottom line is, the big difference between Cheeks and Dawkins comes down to style. If Cheeks was the controlled orchestra leader, then Dawkins is a jazz master, performing spontaneous riffs on the court. His unpredictable play animates the action around him, putting his teammates on full alert for the unexpected pass or move. Cheeks, on the other hand, was more predictable, less likely to force the action on offense. This isn’t to say that one style is better than the other, just that when Cheeks played on the 1983 World Championship Sixers team, his style blended in well with Moses, Doc, and Bobby; just as Dawkins’ style now fits in nicely with Rick, Charles, and company.

Hawkins and Toney also put their own signatures on their respective clubs. Toney was a one-man drama, a player who dominated games, who made no bones about wanting to be the star. In contrast, Hawkins is less likely to take charge, less likely to attract the spotlight. His desire isn’t to dominate the game, but to become a part of it.

Also unlike Toney, who did not take easily to constructive criticism, Hawkins welcomes suggestions that will expand and refine his game. For example, not long ago he fell into a bad shooting slump. The night before a road game with the Lakers, Dawkins called Hawkins into his room. He told Hawkins not to worry, to keep shooting. The shots will fall, he said. Then he made some suggestions to get Hawkins more time and more open space for shots. He said he would penetrate more at Hawkins’ defender, so the defender would have to help out. Then, he told Hawkins, “fade” more to an open shot.

Now the two players meet before every game and discuss their opponents. Dawkins, because of his stint in San Antonio, has a good handle on the Western Conference guards. Hawkins has the book on the East guards. “That exchange of information,” Hawkins says, “is invaluable in helping us play better.”

Say what? If you think a lot of NBA guards sit around and discuss how to help each other out, you’re greatly mistaken. Most NBA guards go out and do their own thing, or else they play the game according to the coach’s instructions. But Hawkins and Dawkins have taken their relationship a step further; they’ve become close friends. Maybe not as close as Hawkeye and Trapper or Butch and Sundance, but they’re working on it. And that closeness has affected the entire team.

“When you have two guys who are like altar boys running your team,” says John Nash, “their good example somehow becomes contagious.”

****

After sitting and talking with Hawkins and Dawkins for hours, one gets the sense that these guys are too good to be true. Neither shows up late for practice or planes. Neither does drugs. Both are loved by teammates, coaches, front-office executives. Both are happily married. Hawkins is a poster boy for the Boy Scouts, while Dawkins appears in ads for the Red Cross. Being around these guys makes you feel as though you’re in the land of Pollyanna, and, quite frankly, it’s a little maddening. The least one of them could do is belch out loud now in the restaurant.

“You know,” Hawkins says to Dawkins, “we’re so alike maybe you better check that your real name isn’t Hawkins and maybe somebody spelled it wrong on your granddaddy’s birth certificate.”

Dawkins shakes his head. “God forbid.”

Sounds like they do everything alike except wear the same clothes. “No way!” Dawkins cries. “Hawk dresses a lot different than me. I am the more conservative type.”

“I’m the kind of guy who’s willing to take chances with my outfits,” Hawk explains.

Dawkins rolls his eyes. “Chances? Is that what you call it?” He breaks out in hysterics. “Really, Hawk, you’re a terrific dresser.”

Hawkins smiles triumphantly. He nods and says, “Thank you.”

For the next few minutes, the two talk about how many people get them mixed up. Can’t tell Hawkins from Dawkins, or vice versa. “I like the guy from ESPN,” Hawkins says, “who gets so excited and screams, ‘That was Hawkins to Dawkins. Or was it Dawkins to Hawkins? Whatever the case, it’s not a law firm.’”

They look at each other. Smile. Slap high-fives. “We’ve sure had a lot of fun this year, haven’t we, Hawk?” Dawkins asks.

“We sure have,” Hawkins echoes. “We sure have.”