[So many books and films have memorialized the Golden Days of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls that, by choice, I haven’t posted much on them. But I should. There are just too many outstanding profiles of the team and its stars to ignore. That includes this penetrating profile of Scottie Pippen from the February 1992 issue of SPORT Magazine. At the keyboard is Johnette Howard, then of the Detroit Free Press. Howard, of course, moved on to shine as a sports columnist (and commentator) for ESPN and the Washington Post. She also published two outstanding books on tennis. Here’s what she discovered about the Bulls’ Mr. No. 2 and the millstone that once shackled him.]

****

The millstone is shed. The suspicions about Scottie Pippen’s mental makeup no longer temper the praise of his striking athleticism or the unique blend of skills that suggest he’s not a forward, but a guard.

From now on, barring some backslide into the bizarre, Pippen won’t have to hear anymore about the migraine that hampered him in Game 7 of the 1990 Eastern Conference finals against Detroit. His inability to finish the Bulls’ 1989 conference final against the arch-nemesis Pistons, following an opening-minute elbow to the head from Bill Laimbeer, has been rendered a career footnote, too.

By grittily acknowledging the rap that he didn’t perform in big games and then authoring the most incendiary stretch of his four-year career last season during the Chicago Bulls’ 15-2 streak to the NBA title, Pippen’s 1991 playoff performance not only liberated him from his playoff past, it won him a new label: bona fide superstar.

“The old questions,” Pippen says happily, “all are gone.”

Life proceeds at a whirlwind pace now. Less than a week after the finals, the Bulls lavished a five-year, $18 million contract extension on Pippen, and he celebrated with a new Porsche 928S—the dream car he’d mentioned as a rookie when asked, “What would you most like for Christmas?” in a routine media-guide questionnaire. Nike swooshed in and gave Pippen his own TV commercial. Arsenio Hall had him on. In September, the U.S. Olympic selection committee bypassed perennial all-star forwards such as James Worthy and Dominique Wilkins to make Pippen among the 10 NBA players on the 1992 team.

“The Dream Team,” Pippen says, breaking into a smile.

By the first week of Bulls’ training camp, there already had been a film crew in town to interview Pippen about the Summer Games, and two photo sessions were shot with Pippen in his Olympic uniform—one taken against the backdrop of a huge American flag; another shot with Michael Jordan and Pippen standing side by side, laughing at the old high-school yearbook trick they were using to make their arms look more muscular for the cameras.

“Gotta bulk up, Scottie,” Jordan says, giggling, crossing his arms and pushing out his biceps with his fists.

“Definitely,” Pippen says, mimicking Jordan’s pose.

“How do I look?” Pippen asks.

The word content comes to mind. But Pippen says no.

“I know my play last season, especially in the playoffs, put me at a different level than I was at the start of the season,” he says. “I definitely think I’m one of the best small forwards in the game. But there’s a lot left for me to do. Once you win one title, you can’t help but talk about winning another one . . . and another one after that.”

Sort of like Magic and Worthy did with the Lakers in the 1980s?

“Maybe,” Pippen says. “Maybe . . .”

****

If Pippen, only 26, always knew that his NBA career would turn out this way, he never said so. Nor did he readily admit how much he’d really been haunted by his playoff flameouts of 1989 and 1990.

Heading into last season’s playoffs, Pippen openly admitted that he was striving for personal redemption. But it was without melodrama or self-pity that he addressed the subject, and it is without gloating that he discussed his leap to the threshold of superstardom now.

From the moment he was drafted by Seattle in 1987, then traded to Chicago the same day for center Olden Polynice, Pippen wanted to be the man who took the Bulls farther than Jordan could alone. Following his rookie year, he underwent back surgery and bounced back gamely. He worked determinedly until he had a deadly jump shot. He was quickly rounding into a do-it-all player who seemed to make his career breakthrough with an All-Star Game berth in 1990.

But Pippen was hurt mightily when he was left off the 1991 All-Star team, even after Boston’s Larry Bird was unable to play. He wondered whether it was because of the “headache.” To his credit, Pippen never ran from the subject of his inability to finish either Bulls’ playoff series in 1989 or 1990. If outsiders blamed Pippen for the Bulls’ successive losses to the Pistons, well, it wasn’t all that different in Pippen’s view either.

“People want results, not excuses,” he says. “If I had been able to play up to my ability, I think we would’ve won.”

He knew he hadn’t responded well to the Pistons’ bullying tactics in either series. After the 1989 playoffs, Pippen and fellow forward Horace Grant were back in the weight room three days later, “just trying to work through the frustration . . . We felt like maybe that’s what we needed to get to the next level.”

Still, the migraine in 1990 was Pippen’s nadir. Critics doubted whether Pippen had even had a migraine, let alone whether one could make him shoot 1 for 10 from the floor. Pippen compared the pain to someone taking an ice pick to his head, and a doctor eventually prescribed eyeglasses to prevent the headaches from recurring. But it wasn’t until a year later, with the Bulls one win away from sweeping the Pistons last May, that Pippen finally revealed he’d been so scared by the migraine that he went to a hospital a few days later and had a brain scan done because the ache in his head still hadn’t subsided. “I was afraid of dying,” he told the Chicago Tribune.

Though Pippen feared long into the 1990-91 campaign that the migraines might return, he still posted career best numbers. But no matter how high he soared during the Bulls’ joyride through the regular season, the doubts about his psyche stayed attached to him like a kite tail. Of all Jordan’s much-maligned supporting cast, Pippen was seen as the one player who embodied all that was good and bad about the Bulls’ chances. He knew it, too. So he sprang into the 1991 playoffs with a vengeance.

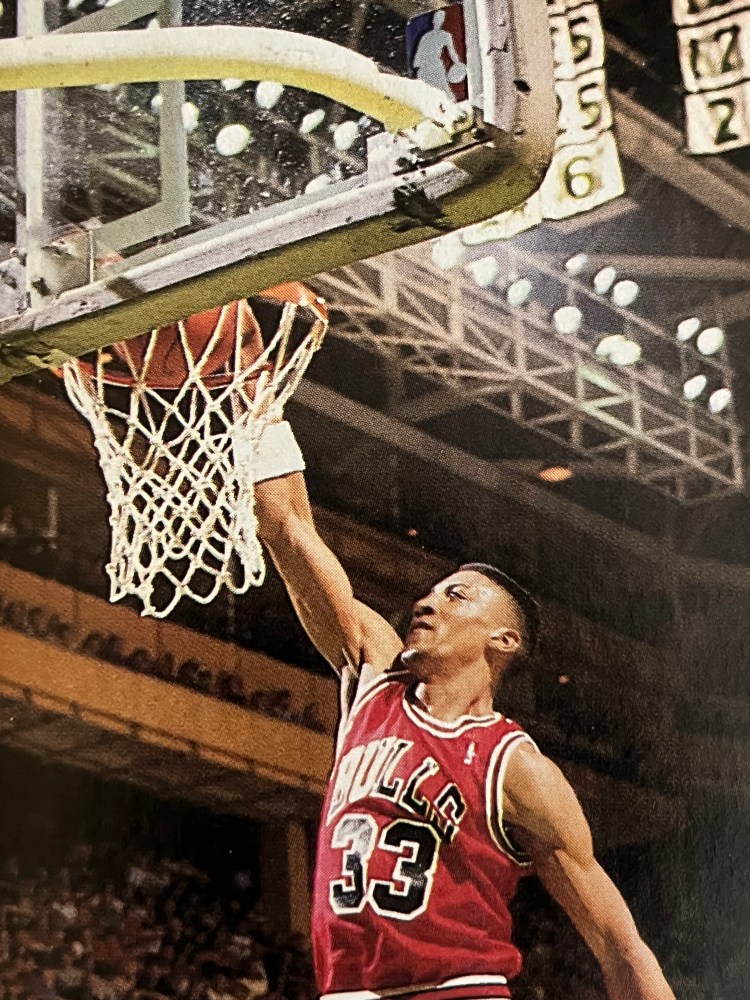

He helped lead the Bulls’ first-round sweep of New York. In one of the more memorable moments of Chicago’s second-round romp over Philadelphia, he soared and dunked—left-handed, no less—over 7-foot-7 Manute Bol. In the four-game blitz of the Pistons, Pippen averaged a glimmering 22 points, 7.8 rebounds, three steals, and two blocked shots. When the Pistons tried to rattle Pippen with the same roughhouse tactics that worked in the past, he was imperturbable.

“I was going to dictate how this series was going to go,” he said at the time.

He was even better in the finals against Los Angeles despite the added onus of defending Magic Johnson for games two through five. By the champagne-soaked end, The Vindication of Scottie Pippen was the storyline of the series. “You [writers] labeled him a failure,” Jordan says, “and Scottie’s got a lot of pride. Scottie had to do this. He doesn’t want to be considered a player who takes a dive in a championship situation. He wanted to get rid of the stigma.”

The irony of all the questioning of Pippen’s character was he had hurdled so much just to get to the NBA.

****

Growing up as the youngest of 12 children in Hamburg, Arkansas, a rural town of 3,400 people, nothing portended that Pippen would become a basketball star. In fact, he intended to quit his high school team after 10th grade, the same year his father, Preston, came home from a typically long shift at the local paper mill and collapsed on the floor of their home, struck by a massive stroke. Paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair after that, Preston Pippen never got to see his son play basketball until the family was sent a videotape of Scottie’s first game with the Bulls.

His dad’s reaction?

“The stroke even took away his speech,” Pippen says. “But my mom told me he cried.”

Though Pippen rejoined his varsity team after a one-season stint as the football team’s manager, not a single college recruited him to play basketball. “He was only 6-1, about 145 pounds, and there was nothing special or flashy about him,” says Donald Wayne, Pippen’s high school coach. “People would ask me all the time, ‘Why are you starting him?’”

Even attending college seemed unlikely for Pippen until Wayne called basketball coach Dan Dyer at the University of Central Arkansas. A deal was struck: Pippen would go to UCA as the basketball team manager, and he qualified for an educational grant to help pay his way. The idea of playing for UCA struck Pippen only after he arrived. He says he was competitive in some informal pick-up games that the players held. Then two players left the team, and Pippen was in the lineup.

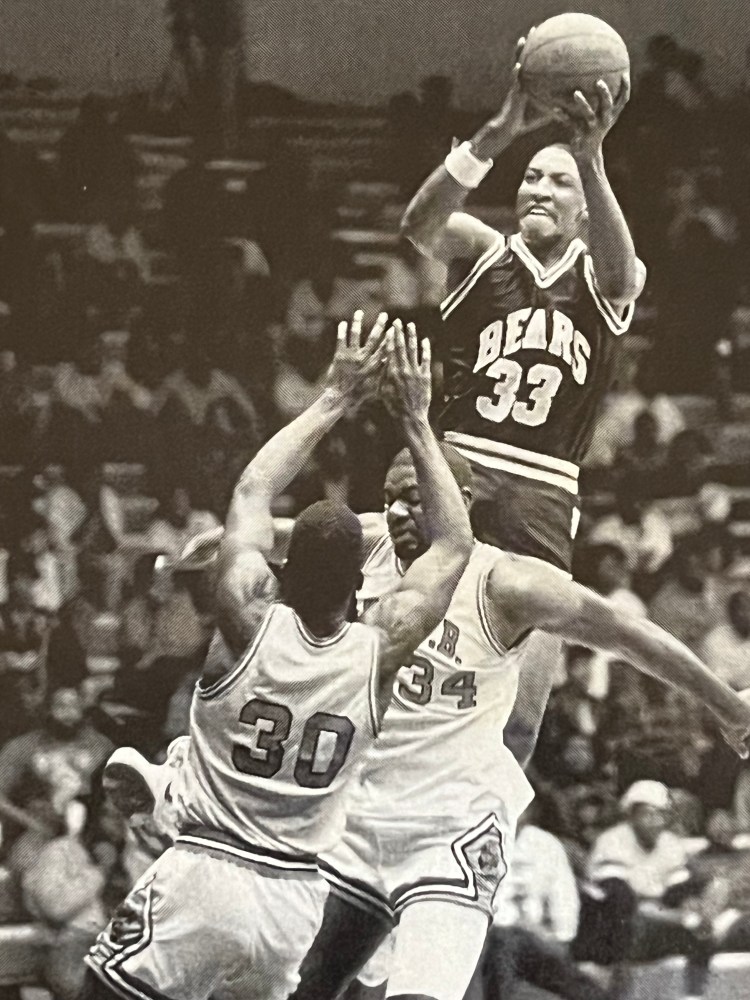

By the end of his freshman year, Pippen was the best player on the team. By his sophomore season, he had sprouted to 6-5, gained some weight, and averaged nearly 20 points a game. That last statistic alone might’ve attracted the NBA’s attention then—if Pippen had been playing in the ACC, or even the Colonial Athletic Association. But Central Arkansas is a tiny NAIA school that lies 30 miles outside Little Rock. UCA’s conference doesn’t stretch beyond the Arkansas state line. The Bears’ opponents during Pippen’s senior season included the likes of Ouachita Baptist and the University of the Ozarks.

By then, NBA scouting director Marty Blake was onto Pippen. And Bulls GM Jerry Krause, who’d gambled on small-college stars such as Charles Oakley and Earl Monroe in previous years, dispatched Billy McKinney to take a look. Though McKinney, then a Bulls scout, called UCA’s competition akin to “amateur night at the U,” Pippen had obvious talent. The Bulls projected him as a high second-round pick, and Krause still thought he was sitting on the steal of the draft until the spring of 1987, when Pippen—to Krause’s unmitigated horror—starred at every pre-draft camp he attended.

Suddenly, everyone in the NBA wanted to know about this gangly kid with the knife-blade build. But Krause wasn’t about to be outmaneuvered. On the eve of the draft, he swung a brazen deal in the wee hours of the morning: Seattle agreed to take Pippen with the No. 5 pick overall—provided neither Reggie Williams and Armon Gilliam were available—then trade him to Chicago for Polynice, whom the Bulls took at No. 8. Chicago also threw in a second-round pick and gave Seattle the option to exchange 1988 or 1989 first-round choices.

“At risk?” Krause says. “Let me put it this way: If Scottie hadn’t been what we thought he could be, he’d have gone down as Krause’s Folly. I’d have been ripped from pillar to post. I’d have gotten crucified with a dull typewriter.”

Pippen made a forceful impression during his first few days of Bulls practice, when he insisted on guarding Jordan again and again. (“He can’t do anything to me that hasn’t already been done to somebody else,” Pippen joked at the time.)

By his second season, he was starting. When he had accumulated enough money from his first pro contract, he moved his parents into a new home. They’d only been living in it a few months when Pippen father died during the Bulls’ 1990 playoff series against Philadelphia.

This time, it was Scottie’s turn to cry.

****

Pippen’s jumping ability allows him to elevate over bigger men and score. He can grab a rebound, bring the ball downcourt himself, make the dazzling assist or drive to the basket for a net-hissing dunk or pull up and bury his jumper from 15 to 17 feet away. He has so much quickness, he can recover from defensive gambles and still make it difficult for his man to score. But until Bulls coach Phil Jackson took over three seasons ago and allowed the 6-7 Pippen to do a little more of all that, it was hard for Pippen to carve out exactly what his role should be.

All of the Bulls have had to make their own uneasy peace with playing in Jordan’s shadow and grapple with the question of when to defer to their star or assert themselves instead. Jackson has suggested that Pippen’s personal turning point came in the fall of 1990, after Pippen posted a triple-double during a West Coast trip. “I think Scottie realized that, even though he barely scored in double figures, there were plenty of other ways he could help his team win besides just scoring,” Jackson says.

Rivals began to notice with a mixture of admiration and despair. Pistons coach Chuck Daly estimated that Pippen was the Bulls’ playmaker—or “point forward”—50 percent of the time. Bullets forward Bernard King called Pippen “the transformed player” and “one of the few guys who’s a complete player in the NBA.” The Bulls also committed to a full-court pressure defense, and Pippen and Jordan spearheaded it so ferociously that Bulls assistant coach Johnny Bach took to calling them “our snapping, scratching, and snarling Dobermans” before the playoffs were through. In the title clincher against the Lakers, Pippen and Jordan each played the entire 48 minutes and combined for 10 steals. Pippen also finished with a team-high 32 points.

“I think what came into effect when Phil took over was everyone found it easier to accept their roles because they had the freedom to try contributing a little more,” Pippen says. “It’s a delicate thing to be in this position, to come in as a top draft pick, to want to be treated as a top-caliber player in the league, and find yourself constantly overshadowed by someone like Michael. But the only way we could have gotten better was to let us go out and play and see what else we’ve got. If we’d kept being held back, we’d have never known.”

Though he’s happy to have exorcised his playoff past, Pippen insists there are more things he must do to certify himself as a here-to-stay star—things such as contending for more championships and annually making the first-team All-NBA squad and the All-Star Game. He also says he wants to be consistent over time—and by consistent, it’s understood what he really means is consistently great.

The mordant questions are gone now, replaced by happier ones. “Now the one thing I get asked most is ‘Will the Bulls repeat?’” Pippen says with a smile.

Time to show everyone else what a lingering headache he can be.