[In the late 1980s, when a young Horace Grant replaced the departed Charles Oakley in the Chicago Bulls starting lineup, Grant’s play brought mixed reviews. The critics grumped that Grant was certainly athletic and worked hard, but he wasn’t nearly as tough inside as the barrel-chested Oakley. Wrote one critic: “Grant’s repertoire consists of a little bit of this and a little bit of that. He’ll shoot the turnaround jumper, jump-hook shots from either box, fill the lane on the break, and crash the offensive board . . . Still, he doesn’t always show up and isn’t yet an every-night performer. Chicago definitely missed Oakley’s enforcer qualities; alas, Grant doesn’t have an ounce of bad boy in him.”

By the 1992-93 season, Grant had battled enough Detroit Bad Boys to know how to enforce his will inside. “Jordan and Pippen supply the pyrotechnics, Grant wears the hardhat,” that same publication revised its opinion. “He’s the grunt of the outfit, willing to do the dirty work. ‘Just a pleasure to be around,’ said one of his many supporters. He’s a self-made player.” And a favorite teammate.

The article that follows builds on some of these themes to provide a snapshot of Grant during his prime NBA. The article, published in the magazine Street & Smith’s 1992-93 Pro Basketball annual, comes from one of the blog’s favorite writers, Fran Blinebury.]

****

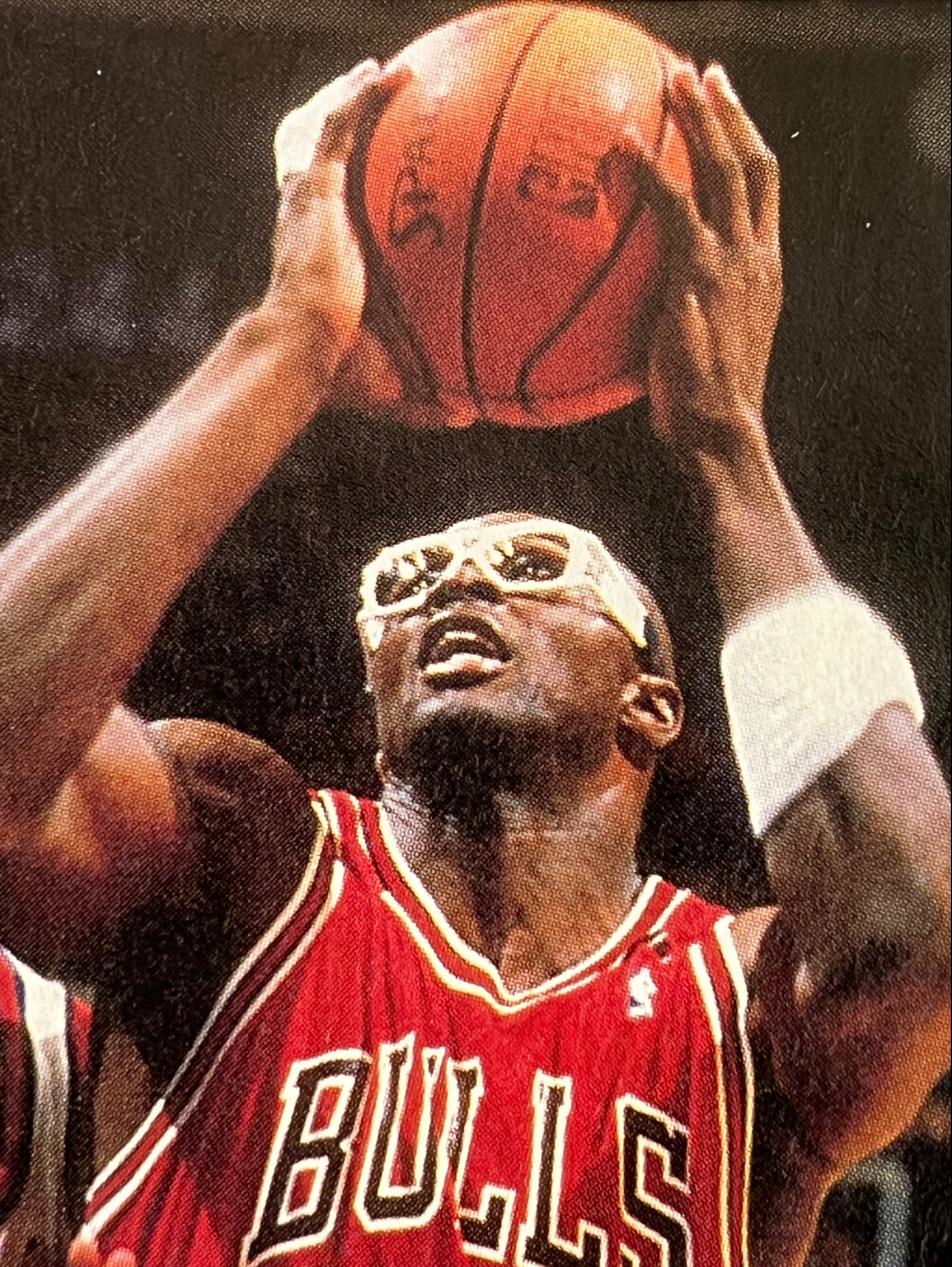

Horace Grant is the twin brother of Harvey Grant of the Washington Bullets, but so many times you get the feeling that Horace is two completely different people all by himself. There he is adeptly filling the role of power forward—the most thankless job on any NBA team—for the Chicago Bulls, thriving in a world full of sharp words and sharper elbows down in the area underneath the basket. And there he is with that warm grin on his face and the pleasant words for all of the kids in the housing projects in the worst of the inner-city neighborhoods.

If Chicago is the City of Broad Shoulders, then Grant is the Bull who most belongs. He is the one who spotted a homeless man across from the team hotel in Philadelphia while the Bulls were in town for a 1991 playoff series and took the man in and got him a room for the night. He is the Bull most likely to be found across the street from Chicago Stadium in the Henry Horner Homes project, trying to provide hope and inspiration to all of the underprivileged kids who can’t afford a ticket to a game, but still need to have their heroes.

“You’d better give something back,” Grant said. “You’d better do something in this world besides hit the jumper.”

Horace and Harvey Grant grew up in poverty. “But it wasn’t city poverty, it was country poverty,” he said. “Our situation was more like needing an extra dollar now and then to get something. What these kids need is just to have some hope. They need to know that somebody is thinking about them sometime.”

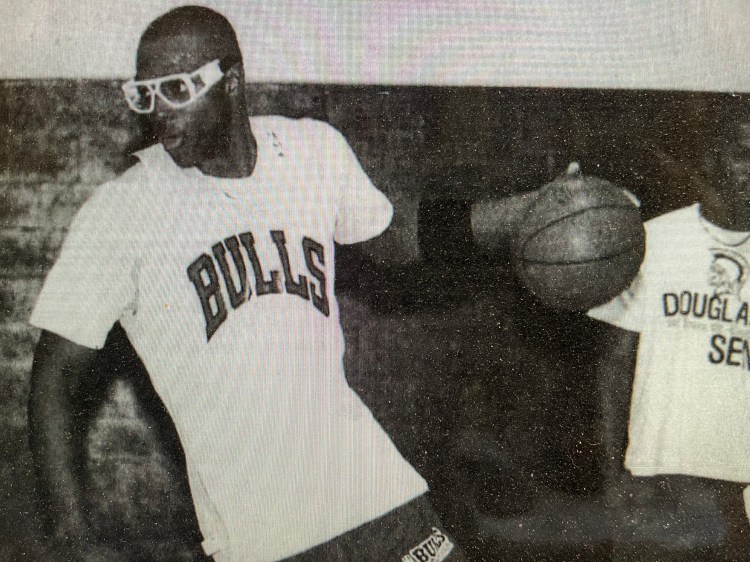

So the kids with hunger on their faces and in their bellies stand around on the streetcorners, and they wait for Horace to drive up. They ask him for extra tickets. They talk to him about how he became such a great basketball player. They ask about his life.

“One of the ridiculous things about our success is that there are people living right across from the stadium who have never been inside the stadium,” Grant said. “One or two people, whether it’s myself or Michael Jordan or Craig Hodges or anybody, can’t do anything about changing everybody’s life. But the least we can do is go over and talk to them once in a while, be a decent human being.”

Grant is the most thoughtful and introspective of the hard-charging Bulls. There may have been times early in his career when his easy-going manner was seen as a weakness. But as Chicago blossomed into a championship team, it became clear that he was one of the Bulls’ biggest strengths.

“Horace has accepted the fact that power forward is a rotten job where you are not going to get much gratitude,” said Bulls assistant coach Jim Cleamons. “Night in and night out, you not only get the short end of the stick, but the dirty end as well. Nobody appreciates what Horace does except the coaching staff. You have got to be satisfied knowing that if you don’t sacrifice and get the rebounds, your team doesn’t win. Regardless of whether Michael Jordan gets 40 points or Scottie Pippen gets 30, Horace knows that if he doesn’t hit the boards hard, we don’t win.”

Simply put, he is the third wheel in the Bulls’ attack, behind Jordan and Pippen, and it is a role he could be saddled with through his entire career in Chicago. He certainly wants to remain with the Bulls and continue to contend for titles, but there is also a natural urge in all athletes to be recognized for individual accomplishments as well. Grant was overlooked by the NBA coaches when it came time to name the reserves on the 1992 Eastern Conference All-Star team last season. Jordan and Pippen, of course, were there for starters.

“I spent a day thinking about not being selected,” he said. “But after that, I went back to being my normal self, being cheerful and smiling, doing the things that I normally do. I definitely want to become an all-star someday. I want the opportunity to showcase my talents. That is one of my goals.

“For it to happen in Chicago, that’s a long shot, because of Michael and Scottie. I know the grass may seem green on the other side, but it’s not as rewarding as being on a championship team. That’s the main reason we’re all playing—to win it all. Everybody has to know his place.”

Grant’s place on the Bulls has become much more than just the blue-collar worker who toils mostly in anonymity. He has become the Bulls’ conscience. It was, after all, Grant who stood up to Air Jordan himself on the first day of training camp last season.

[As the story goes] following the Bulls’ title in 1991, many of Jordan’s teammates began to sense a distancing of the superstar from the rest of them. When Jordan missed a scheduled appearance by the team at the White House, many were bothered. But only Grant confronted Jordan. He knew that the team had a difficult time overcoming internal strife in gaining its first championship, and he didn’t want the problems to grow as Chicago tried to defend its title. First Grant spoke out publicly, then he spoke privately to Jordan. It was not a one-sided conversation, but a dialogue that cleared the air and sent the Bulls on their way to a 67-15 record, the third-best in the history of the NBA.

The 6-10 forward arrived as the No. 10 overall choice in the 1987 draft with plenty of promise. But he started slowly, and his game did not, quite literally, come into focus until two seasons ago when Grant began to wear prescription goggles that enabled him to see more clearly in games. Now he has been part of a championship team, and that experience has clearly given him more confidence and raised his production.

Nowadays, when Grant returns to the bench after another solid night of work under the boards, he is frequently greeted by assistant coach John Bach, an old Navy man, delivering a salute. “It’s a sign that he did a helluva job,” Bach said. “Whenever you go to war and come back a winner, you receive a salute. It’s a nice reward.”

The warrior nods, “As the years go by, I will get the respect and notoriety I deserve,” he said. Which means that more people will come to realize that Horace Grant is as good a player as he is a person.