[In the early 1970s, virtually all NBA general managers believed that for their teams to have a prayer of winning a championship, they needed a dominant big man policing the middle. That’s also why common sense dictated that the top pick in the annual NBA draft should be the most-promising seven-footer on the board, such as Lew Alcindor and Bob Lanier. Or if it was a lean year for capable centers, the next-best option was to grab a big, athletic forward. Someone like Elvin Hayes, who could score, rebound, and hold down the middle until somebody taller and wider could be found.

Guards? Well, exceptions could be made for taking a guard first if the backcourt player was universally hailed as a can’t-miss, one-of-a-kind generational talent. Like Michigan’s dazzling swingman Cazzie Russell in 1966. Or Providence College playmaking sensation Jimmy Walker in 1967.

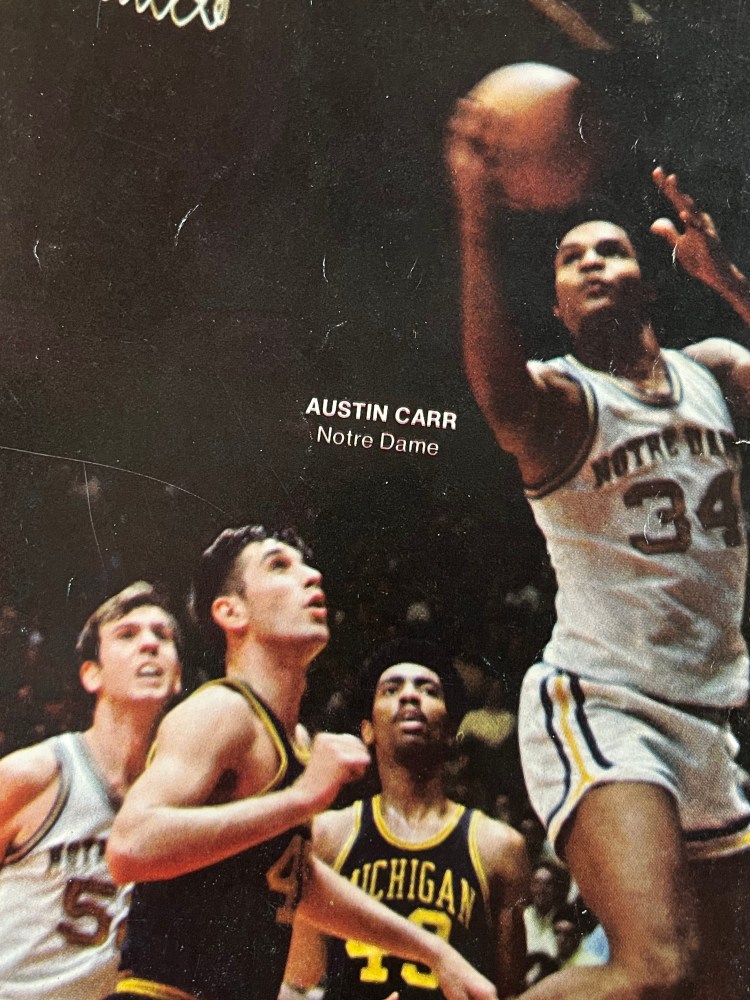

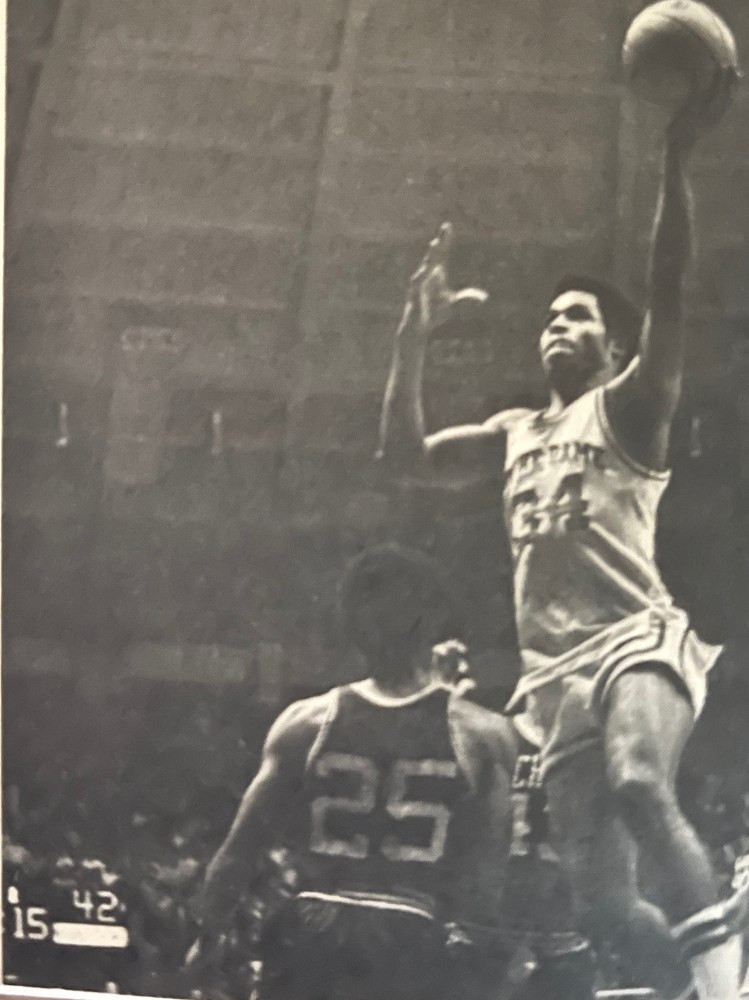

Or, for the purpose of this blog post, Notre Dame’s high-scoring Austin Carr in 1971. None of his fellow collegians, it seems, could stop Carr from going off for 30, 40, or even 60 points. The article that follows, titled “Austin Carr: Boys in the Basement,” lays out why pro scouts were so bullish on this kid from Washington, D.C.. The seasoned journalist Jim O’Brien is at the keyboard, and his article ran in the 1970-71 issue of the Street & Smith’s College and Pro Basketball Yearbook, where he also served as the magazine’s editor.

After O’Brien’s longer piece, I’ve got some shorter check-ins on Carr going pro and the high expectations that greeted him as the NBA’s top draft pick.]

****

“His room’s in the basement. Down those stairs there . . . turn right at the bottom . . . down the hallway, then right again. You’ll see (smile) a big stuffed moose-head hanging from the door. His room is the next one on the left.”

The stairs creaked. The walls were weak green, probably painted with something out of an army surplus store. At the bottom, a sign catches the eye:

WELCOME TO THE GHETTO

“You know, we’re making progress,” a man would say a few days later on a similar visit, “when students can kid about such things.“

Down a dark hallway . . . a naked lightbulb at the end outlines the dark, ominous moose-head. It’s something straight out of the Addam’s family attic . . .you know, TV’s monster family. “You should see some of the parents jump when they’re visiting,” squeals Sid Catlett, “and come around that bend unawares.”

“I would say Austin Carr will definitely be the outstanding player in America next year,” said Kentucky’s Adolph Rupp.

He said it after Austin Carr, Notre Dame’s 6-3 guard, scored 52 points against Rupp’s Wildcats, then rated No. 1 in the nation. Kentucky knocked Notre Dame out of the NCAA tourney, 109–99, but The Baron was impressed.

Four days earlier against Ohio U., Carr clicked on 25 of 44 field goal attempts and racked up 61 points altogether to break Bill Bradley’s NCAA tourney record of 58. “Before the game,” Coach John Dee declared, “I gave him a free-hand on shooting, and he overdid it.”

Near the outset of the season, Carr scored 1,009 points playing against the best in the land. He averaged 38.1 points per game, second only to Pistol Pete Maravich of LSU, who averaged 44.5. Pete’s a pro now with the Atlanta Hawks. There’s room at the top.

Carr came to the door of his room at the bottom. Mention of the moose-head brought a big smile to his handsome face. Catch the dimple in the corner of the mouth. There’s a real twinkle in the glad eyes. It’s a wonderful smile—it really is—and, at once, one feels at home.

So does Austin. It’s a high-ceilinged room. Reminds you of a place they stored you in a military outpost in Delta Junction, Alaska. There’s a tall metal locker in the corner, drab-gray, of course, with a basketball atop it.

Pipes, same weak-green, crisscross the ceiling. There’s a portable record machine, a pile of 45 rpms, Diana Ross and the Supremes, stuff like that, a telephone, a white wash bowl, loads of books, a bunk.

“I asked for it,” Carr volunteered. “I wish it were larger, but it belongs to me. I like it. I’m very comfortable. I wanted a single, and this is the only place you can get one.”

Sprawled on the bed now in a plum-colored underwear shirt, ragged black Bermuda shorts, and an economics book opened on his pillow, Carr was convincing when he said it suited him just fine.

Apologies to the school official who said, “Don’t make it out to be a slum.” Forgive us our trespasses, but it was a shock. The room seemed best suited for an agent of the French underground or a hideaway for Anne Frank.

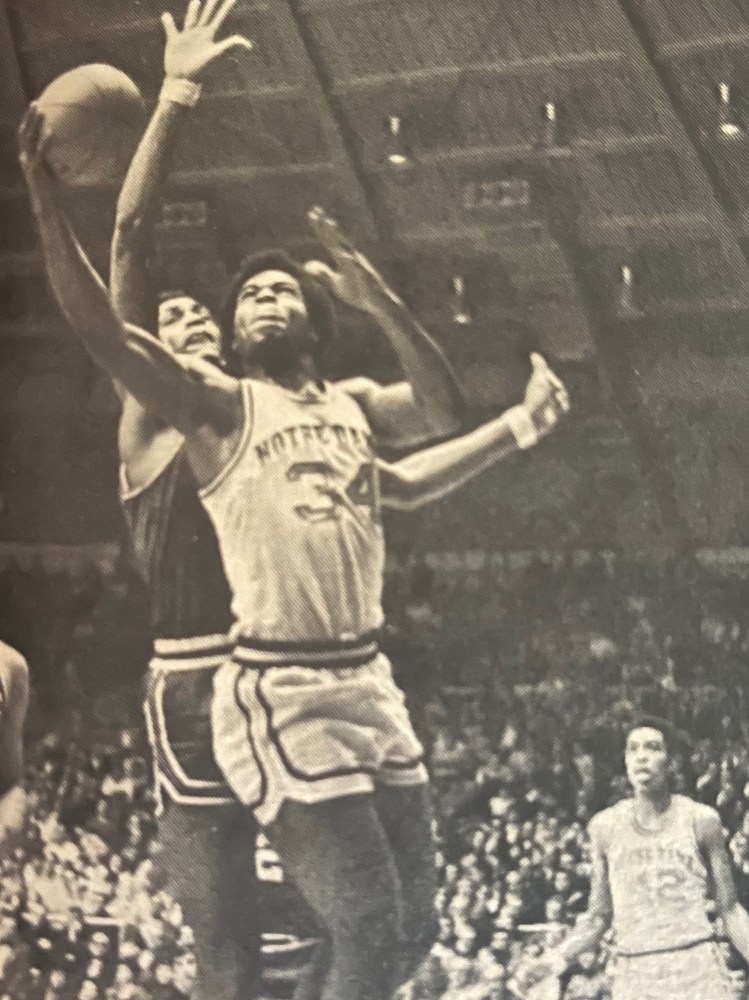

Notre Dame’s Athletic and Convocation Center couldn’t have held another person. Al McGuire and his Marquette Warriors were the opponent—for the first time in 11 years. Old wounds had been healed, and the two Midwest Catholic colleges were back together in a basketball game that later would be recalled as one of the most exciting of the season.

Two nationally ranked teams pitted against one another, two student bodies out en masse (the Marquette kids rode several buses 180 miles from Milwaukee), and two All-America juniors, Carr and Marquette’s Dean Meminger, all under one roof—which threatened to blow off at any minute.

With 1:57 to go, Carr hit a field goal which gave the Irish a 70-65 lead.

Meminger and teammate Gary Brell both hit baskets to close within one point.

Dean dropped in a free throw to tie it with 1:07 left at 70-70.

A technical foul was called on Coach McGuire with 19 seconds to go, and it looked like the game was over. He’d have hell to pay with the priests back at school, trying to explain his bench behavior.

There aren’t too many better foul shooters in the country than Carr (82.7 percent). How could he? He missed it!

With five seconds to go in the five-minute overtime period, Carr grabbed a rebound, but the ball bounced off his ankle and went out of bounds. Marquette called timeout with an 81-79 lead. Carr’s chin was on his chest as he shuffled to the sideline. The Warriors whooped it up, embracing one another in a victory dance.

What a weekend to come see Austin Carr! He’ll be in a great mood. He’s the goat of the game . . .

It was at the end of the eight-day period in which Notre Dame played the top three teams in the nation (UCLA, Kentucky, and South Carolina) on the road. Carr scored 110 points against them. Remember Rupp said “he played a perfect game” against his team, too.

“He’s fantastic,” said South Carolina’s John Roche, an All-American guard himself. “I can’t imagine anyone playing any better. That’s the best individual performance against any team I’ve ever played on.”

Against the Gamecocks, Carr hit 14 shots in succession in one streak and 19 of 24 altogether. “We tried every defense imaginable on Carr,” said Coach Frank McGuire. “Nothing could stop him—not man-to-man, zone, double-team—nothing. I’ve seen a lot of great ones, and he is as good as any player I’ve ever seen.”

That would’ve been the night to see Carr. Not this particular afternoon. With five seconds left in the overtime, Dee made two substitutions, sending five guards into the game. They didn’t guard against the inbound pass, so there were five against four. Notre Dame’s Jim Hinga stabbed at the pass, knocking it toward teammate Tom Sinnott. He started to drive to the basket, dropping off the ball at the last possible second to Carr, who laid it up with one tick showing on the clock, to tie the game at 81. “I didn’t think there was any time left,” Carr would say later.

Carr comes through with seven points in the second overtime, and Notre Dame wins it, 96-95. Altogether, he scored 48 points. He’s a hero . . .

The handwriting on the placard in Carr’s room was rough, but the message meant a lot to Austin. It read: Nice Going, Austin. The Whole Bsmt Salutes Your Performance. Dean Still Just a Dream but the Fans Will Never Forget “Augie.”

Augie, just one of the boys in the basement at Notre Dame. That’s the way he likes it. “We feel like there’s sort of something symbolical about us all living down here,” he said, smiling. “We identify with each other. Sometimes it’s very interesting down here.”

Through the thin walls you could hear the hearty voice of Sid Catlett visiting with teammate Collis Jones, who lives there. Later, they’d stop by and call out to Carr. “We’re going to Mardi Gras,” Catlett said, peeking into the room. “We’ll catch you over there later.”

The Mardi Gras, a campus carnival . . .

New Orleans . . . one of the big towns where Notre Dame showed off its basketball team last year. That’s where Carr scored 70 points in two games and was named MVP of the Sugar Bowl tournament.

Johnny Dee digs the big cities . . . [Notre Dame] plays the best before the big crowds . . . take your chances . . . Invite all those Catholic kids to come over and see the team in action . . . Cheer, cheer for ol’ Notre Dame.

This year they’ll play in Chicago three times, New York twice, St. Louis, Louisville, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh. “Football’s a real plus for us,” said Dee. “We live in its reflected glory. The opposition tells the kids we’ re a football school.”

Basketball is big-time at the South Bend boy’s school, too. The arena where the Irish play their home games cost a cool $14 million. It’s sorta funny. You could come by a room like Carr’s for $4 a night in the worst of neighborhoods.

When the campus is covered with snow, Sorren Hall stands out in the night as one might imagine The House of Usher would appear. It’s the oldest dormitory on campus. It’s been a favorite for years among the athletes. The list of All-American football players who lived there could stock a pro team. “Actually,” said an alumnus, “it’s a prestige address.” This is where Notre Dame stores its star athlete.

Carr has seen those athletic dormitories at other schools. They look like the condominiums on Miami Beach, all tinsel and no warmth. They don’t appeal to Austin. “I don’t go for that stuff,” he said. “It makes you more like a robot. You’re just there for one purpose, and that’s it. You just go back to your cage after practice.

“Here it’s socially slow. No girls. No cars. But it is the right atmosphere for what I need. Here, you’re part of the student body. You find out a lot more stuff about people that way. If you’re going to be a college student, why not live with the students?”

If Dee had heard that declaration, he’d have smiled. He was a star athlete at Notre Dame once upon a time. He was also a student. Today, he is a lawyer, as well as a basketball coach. Quite a combination. The proper perspective, he says.

“We let them spend time with the kids when they come in for a visit,” said Dee, explaining policy. “We don’t make any attempt to roll out the red carpet. We let them see it as it is.”

“This is where I stayed when I visited the school,” said Carr, “right here in Sorren Hall.”

When Carr came for his visit over three years ago, Sid Catlett and Collis Jones joined him on the airplane flight. All of them were All-Met in Washington, D.C. as schoolboys. “And on the eighth day,” kids Catlett, surveying a snowy night, “God created Indiana.”

Catlett, son of the late jazz musician by the same name who played for Louie Armstrong, had been a high school teammate of Bob Whitmore, who’d gone to Notre Dame a few years earlier. The three of them thought of going to Syracuse together. That’s where Dave Bing went, and he was Austin’s idol. (“We thought we’d have a good team,” recalled Carr, “if we all stuck together.”)

Catlett is 6-8 and can be great, as he was against St. John’s last year. He scored 26 points that night and grabbed 14 rebounds. But he’s inconsistent.

Collis Jones is 6-7 and has gotten over his earlier timidity to mix it up under the boards. Now he goes to the offensive boards with a bang, and one night when Carr scored 50 against Butler, Jones had 40. (“Collis is our anti-pollution expert,” says Dee. “He grabs a lot of garbage out of the air.”)

They’re all seniors this season, look out.

None resent Carr. “He has that little something,” says Dee. “Everyone wants to play with him. The night he scored 61 points, he’s such a great kid [that] the other kids on the team wanted him to get the record.”

More records are on the horizon this season. By midseason, he should pass all-time leader Tom Hawkins as the highest scorer in Notre Dame history.

And on the ninth day, God created Austin Carr.

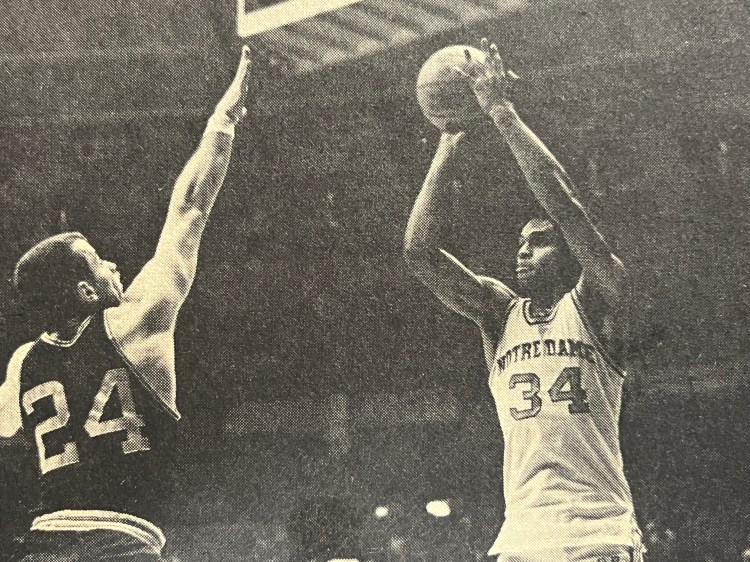

“Nobody’s really going to stop a guy like Austin Carr,” says Don Donoher of Dayton. “You just have to try and keep him from going wild.”

“Everybody talks about Carr’s shooting,” says Kansas coach Ted Owens. “You get the impression that he’s a gunner. Carr never takes a bad shot. He’d rather pass off than force a shot. Carr has few equals as a team player.”

“We’re at the point now that we’re almost as good as anybody,” says Johnny Dee. “We only need a small amount of improvement. I think there’s enough talent. We have the ability to compete with anyone. There are going to be some great teams this season . . . UCLA, South Carolina . . . the three of us figure as the top three teams in the country.

“As for Austin, he’s the greatest college player I’ve ever seen.”

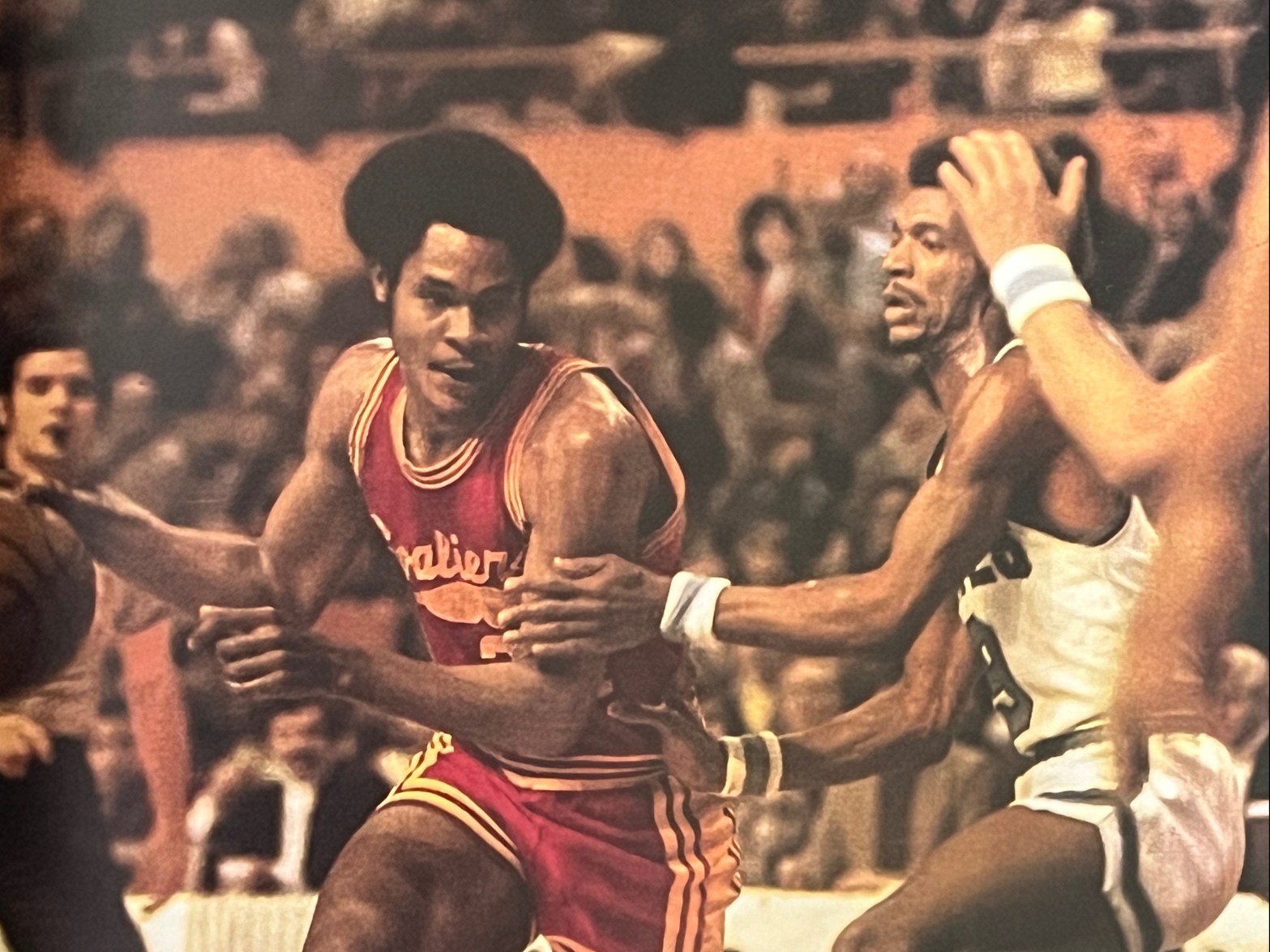

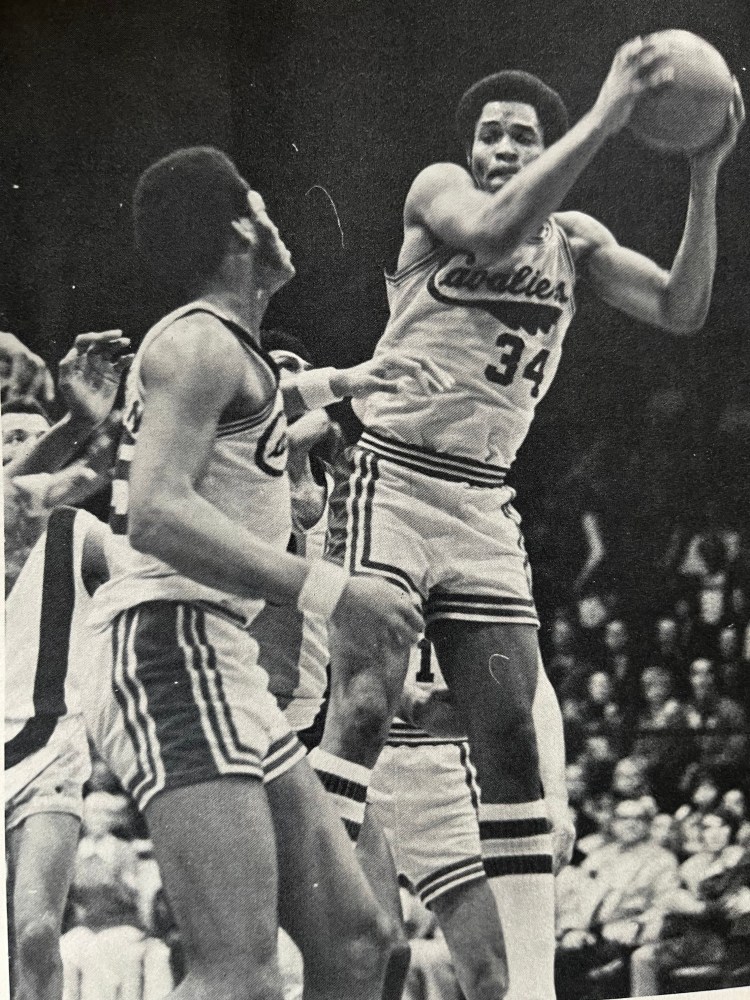

[Carr had a fantastic senior year at Notre Dame, pouring in 37 points per game. The lowly Cleveland Cavaliers grabbed him first in a so-so NBA Draft, ahead of standout forward Sidney Wicks (UCLA), center Elmore Smith (Kentucky State), and highly-regarded forward Kenny Durrett (LaSalle). Eyes rolled immediately. Who would take a guard over these bigger guys?

“Please don’t get me wrong,” said John Wooden, Wicks’ legendary college coach and basketball oracle. “Austin Carr is a fine player and a fine person, but I feel Wicks is a better all-around player . . . Wicks is a real good big man, and a big man can do more in helping you win games than a good smaller man.”

Notre Dame coach Johnny Dee countered by stating the obvious. “Carr is a great free-throw shooter, a fine outside shot, drives well, he’s great one-on-one, he’s good in traffic, gives up the ball well to the open man, plays good defense with good reactions, has enthusiasm, had dedication, has leadership, and hustles.”

“Yet,” lamented a scribe on the Cleveland Plain-Dealer sports desk, “can [Carr’s] basketball talents be any greater than Oscar Robertson’s, who probably is the best all-around player in the NBA?

“In 10 years at Cincinnati, Robertson was not able to bring a championship to that city. The combination of Jerry West and Elgin Baylor did not accomplish the task in the early 1960s for Los Angeles. Only with the acquisition of [center] Bob Lanier have the fortunes of the Detroit Pistons started to look up. Previously, the backcourt combination of Dave Bing and Jimmy Walker had not turned the team into a winner.”

Carr prepared to rebut his naysayers the old-fashioned way. He worked his tail off during the summer training with Walt Frazier. “He was simply fantastic,” Carr said of Frazier. “We not only practiced a lot against each other, but he showed me what the pro game was about. He got me ready to play defense, something I never really concentrated on in college, and he taught me about hitting the open man.”

As training camp approached, Carr broke a bone in his foot, then broke another one. He spent the first months of his rookie season on the mend and would appear in just 43 games. But Carr adjusted quickly to the pros, just like everyone expected. And this final piece, from the 1972 Pro Basketball Almanac with no obvious byline, fills in the blanks on those expectations in Clevelan heading into the season opener against the Buffalo Braves.]

The first game will be against Buffalo on October 15. It really shouldn’t be anything out of the ordinary. The Cleveland Cavaliers played a home opener last year, losing to the Rockets, 110-99, before 6,144 in 11,000-seat Cleveland Arena, and they will play many more in the future. But this one will be different, perhaps extraordinary.

Cleveland Arena will be filled with the curious, the cynical, and the connoisseurs that night. And those who can’t get there will dissect the box score the next day to see how he did. He, of course, is Austin Carr, the Black Messiah of Cleveland. The Second (and shorter) Coming of Lew Alcindor, who, it is hoped, will bring respectability to Cleveland with the rapidity that Alcindor brought to [expansion] Milwaukee.

The questions are elementary. Can Austin Carr relieve the humiliation of the Cavaliers, who last season won only 15 of 82 games? Can Austin Carr do in Cleveland what no man has done since Jim Brown retired after the 1966 football season? In other words, can Austin Carr make it big and in a hurry?

A similar question was asked last year about Pete Maravich, and, as it turned out, he made it neither big nor in a hurry. But Austin Carr isn’t Pete Maravich. For one thing, Carr is a natural. He wasn’t force-fed basketball by an overzealous father-coach, as was Maravich. Carr played basketball because he was good at it; because, when he went down to the playground in the River Terrace section of Washington D.C., he could do things with a basketball that most of the other kids couldn’t.

“To me,” Carr says, “playground basketball is about 60 percent of my game. That’s where I started. I learned habits on the playground that organized ball just couldn’t develop.”

Among the other things Carr realized on the playgrounds was that he could shoot a basketball very well. So well, in fact, that he earned All-America honors at both Washington’s Mackin High School and Notre Dame, where he scored 2,560 points in 67 games.

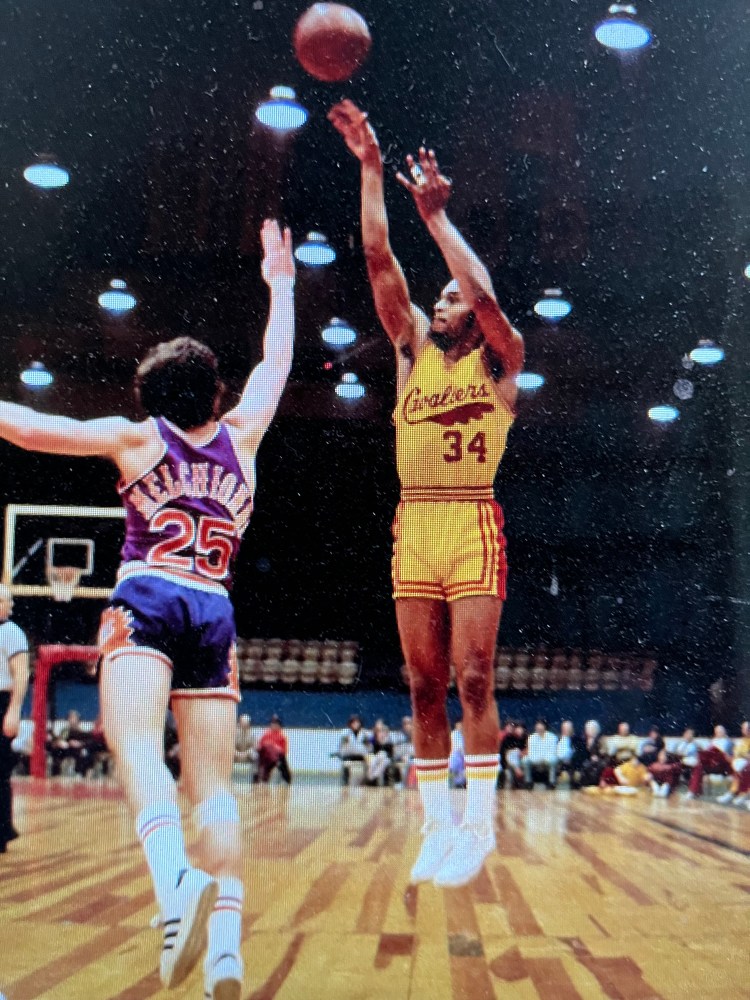

“He’s a pure shooter,” says Cleveland coach Bill Fitch. “There are some kids with better range around, but Austin has the uncommon ability to shoot as well in a crowd as in an unmolested area. And, he has a quick shot, which is essential.”

Fitch might have added that Carr is a smart shooter, too. At Notre Dame, Austin often went low in the Irish’s double-post offense and used his superior jumping ability to shoot over his opponent. He realizes, though, that 6-foot-3-inch, 200-pound guards don’t display such audacity in the NBA regardless of their physical abilities. “I’m going to have to get used to taking most of my shots from the outside perimeter,” Carr says.

But Carr isn’t just a gunner. He is the complete offensive ballplayer. He rarely commits a ballhandling error and says that he likes to play without the ball, too.

That leaves only defense for Carr to worry about. But that’s a considerable worry. Austin, like all of the rookies this side of mortality, will have to go through the hell and the embarrassment that is learning Advanced Man-to-Man Defense (D-53) against such names as Oscar Robertson, Earl Monroe, Walt Frazier, Dave Bing, and Jerry West.

“Defense,” Austin Carr admits, “is going to be the toughest adjustment.”

Fitch agrees. “I don’t believe any rookie is going to play it like he will when he has experience,” he says. “Austin has the mental and physical skills necessary . . . He’s just going to have to make a study of defense and learn what it’s all about.”

The final question with Carr is the most difficult of all, because it is so abstract. But it is also very important, often the difference between a rookie’s success and failure. How will he respond to the public and private pressure to excel?

Carr fielded the question easily. “Everything,” he said, “will be copacetic.”