[With only slight exaggeration, a veritable river of ink has flowed over the decades in celebration of the “Amazing” New York Knicks of the late 1960s through the early 1970s. Stories abound about all the old Knick greats . . . Red Holzman, Walt Frazier, Bill Bradley, Willis Reed, Earl Monroe, Phil Jackson, Jerry Lucas, Dave DeBusschere. With one glaring exception: Dick Barnett. You’ve got to do some real digging to find a good, old-fashioned profile of Barnett.

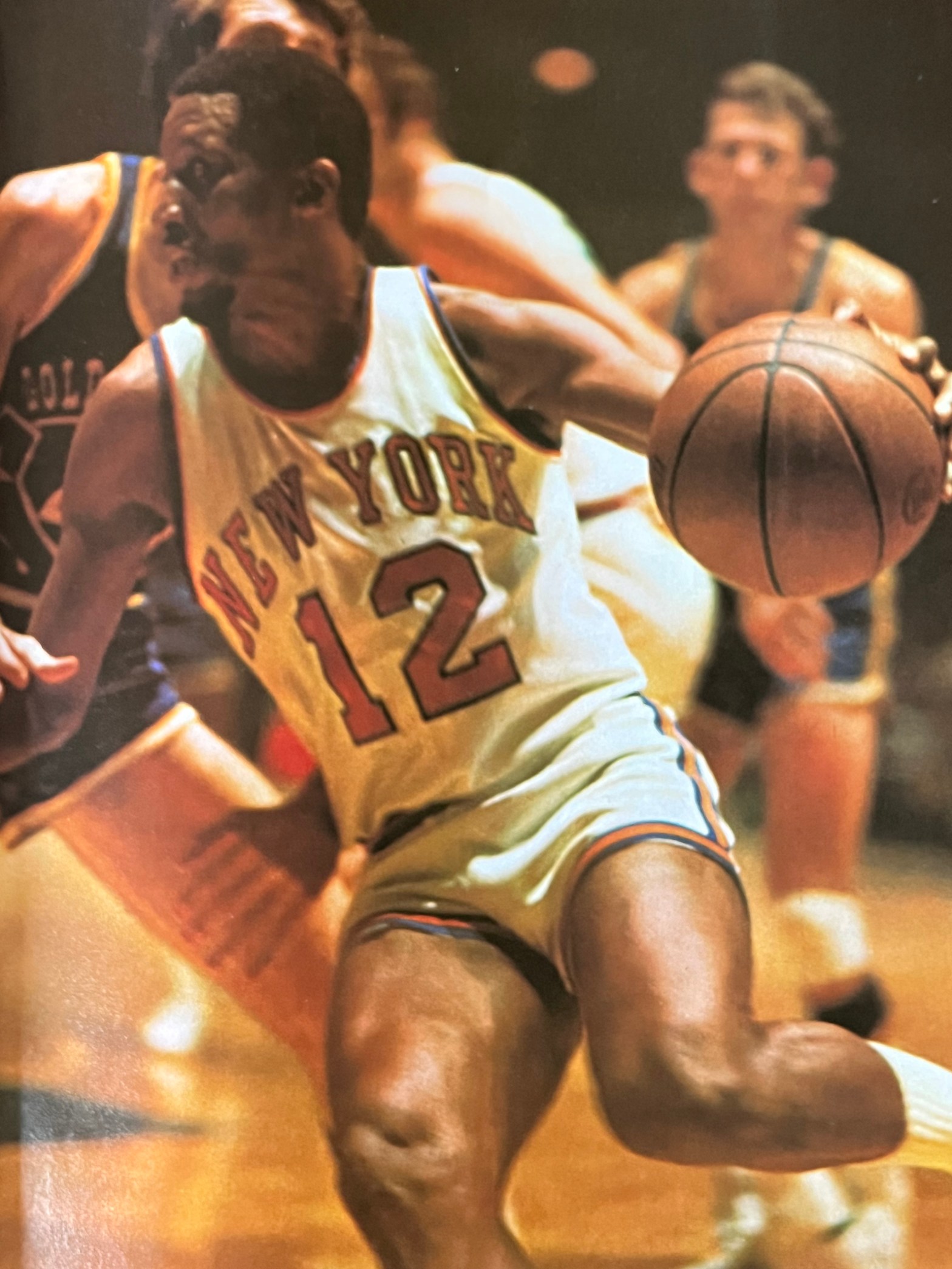

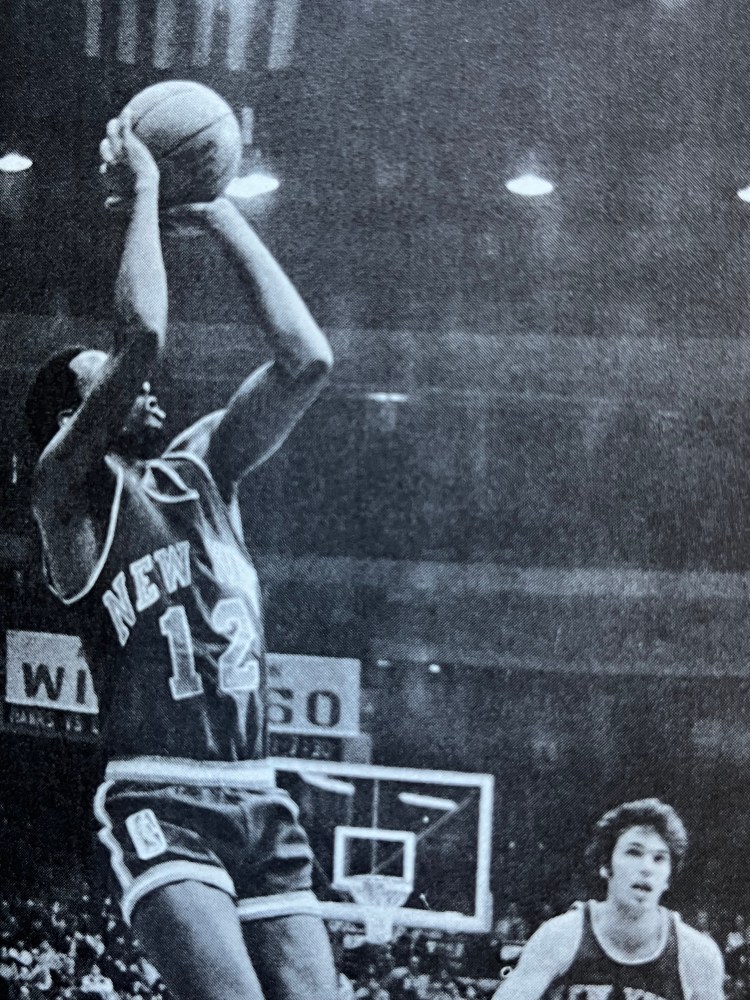

But, alas, I’ve got one for you. It’s from Howie Evans of New York Amsterdam News fame. His profile of Barnett, who had one of the coolest, leg-kicking jump shots, ran in the March 1972 issue of the magazine Black Sports.]

****

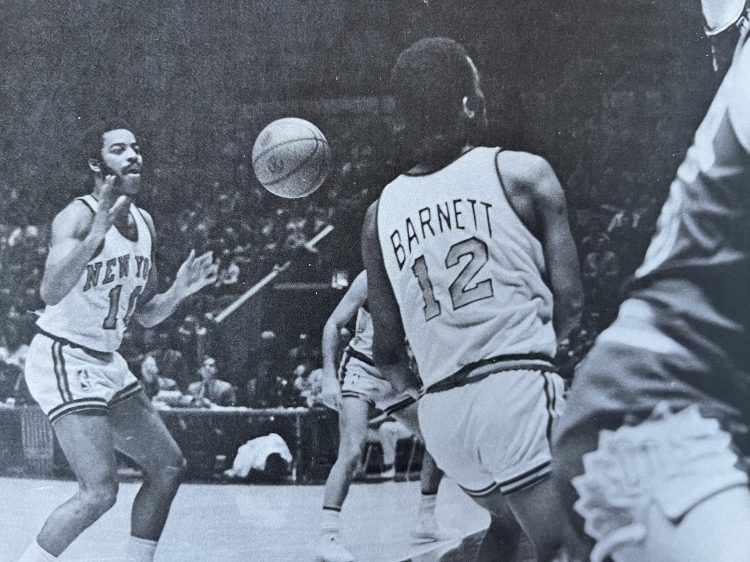

It was a typical post- lost-game, locker-room scene for the New York Knickerbockers. The Phoenix Suns had just defeated them for the first time in Madison Square Garden, and only the hum of whispering newsmen disturbed the otherwise silent players. As usual, the press contingent had rushed over to Walt “Clyde” Frazier, Jerry Lucas, a still-ailing Willis Reed, and Dave DeBusschere. The glamor guys as they are known, the ones always ready with the quick quotes and reasons for winning or losing.

Dick Barnett sat on a table in the trainer’s room, absorbing the whole scene through his sleepy-looking eyes. He appeared to be carefully examining every part of his 35-year-old body. The body that has carried him through 25 years of basketball, 13 of which have been professional.

Barnett, though not particularly favored by the press, is recognized and appreciated by those who count. Namely, coach and general manager Red Holzman, press director Jim Wergeles, his teammates, and the fans who pour into the Garden in record-shattering numbers.

For 20 minutes after the club had entered the dressing room, Barnett sat in the trainer’s room. It was almost as if he knew none of the newsmen wished to speak with him. In a losing cause, he was the game’s high-scorer with 25 points, but still he was ignored by the press.

Why?

“There are certain players [that] the sportswriters like to pick up,” said Dick. “They talk to the guys and build them up because these guys tell them what they want to hear. I’m not one of those guys. I call them like I see them, and I probably have alienated some of the press.

“I’m not bitter or envious because I don’t get as much publicity as the other guys. I approach the whole thing from the aspect that I will be rewarded according to my performances. I’m fortunate to be in New York, where the people are cognizant of my talents and the contributions I make to the ballclub.

“The role I play in New York is one that I am happy with, and the people who really count understand that as long as management appreciates what I’m doing, I have to be satisfied.”

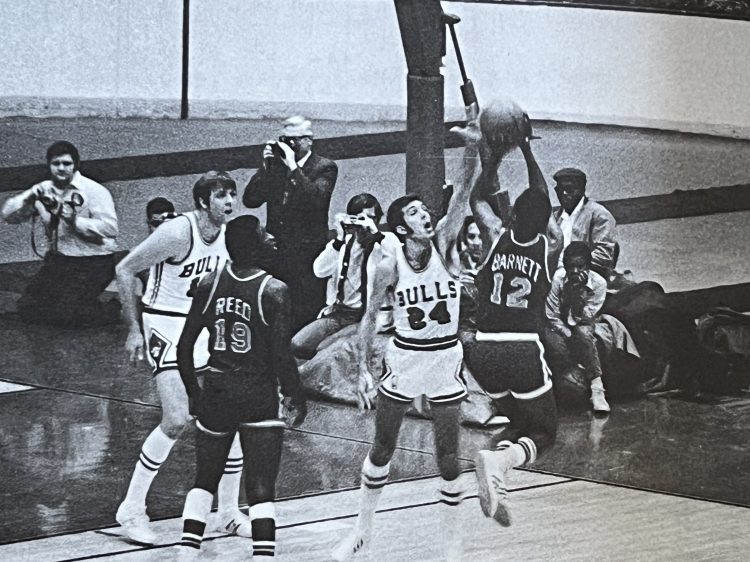

One of the people who appreciates the talents of Dick Barnett is Holzman. “Dick is a student of the game and one of the most knowledgeable guys on the club. He is a helluva guy for a coach to have on the floor. He’s played better the last two years than at any other time in his career. With Willis out, Dick is our captain, and we look to him for leadership on the floor, though he very seldom says anything. We have been together for four years, and he thinks right along with me.”

****

There was a time, when Dick hardly thought at all and kept up a constant stream of chatter on the floor. Those were the days of Tennessee State, where he is something of a legend. Said Earl Monroe, “When I started at Winston-Salem, they were still talking about Dick. That’s all I ever heard my first year there—Dick Barnett.”

To say Barnett was a legend at Tennessee State is an understatement. For three straight years, Barnett let “State” to consecutive National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) titles and made All-America each year. He ended his college career with 3,209 points, 20th on the list of all-time top collegiate scorers.

In those days, Barnett was the flamboyant campus hero. Short haircuts were the style, and Dick sported a hairless dome that earned him the nickname “Skull”—a name that stuck with him for years, and he loved it.

In college, Skull was cocky, loose, and a great ballplayer. There was the night Maryland State was playing Tennessee, and The Skull was just a freshman. He laid back on the bench taking in the whole scene. Some guys in back of the bench started jazzing him about not playing. He turned around and said, “Don’t worry. When the coach needs me, he’ll send me in.”

His coach was John B. McClendon, one of the greatest college coaches of all-time. McClendon heard the exchange and smiled to himself. He couldn’t let the kid know how good he was from the start. It might hurt him later.

But the game got to the point where McClendon knew that he needed the cocky freshman, and so, in went “The Skull.” Closely guarded by Jerry Ford, the Maryland State guard, Barnett let fly his first shot. As it arched through the air, he yelled, “Fall back, baby!” It was heard by everyone in the small gym and became Barnett’s theme song for the next four years. It followed him into the pros, but gradually, as the years went by, it became a thing of the past, just as his cocky mannerisms and flamboyant acts.

“It has nothing to do with basketball,” claimed Dick. “Those changes took place in the process of maturing. Nobody my age is the same as they were at 18, 19, or 20. With maturity, I developed another frame of mind and reference. It affected my approach to basketball and life in general.

“College wasn’t at all like the college I had viewed on television and in the movies. To me, it was just an extension of high school. The biggest adjustment I had to make was being away from home and being on my own. I disciplined myself and academically did better in college than in high school.

“It was great being a college hero. We had a tremendous team with John Barnhill, Porter Merriweather, and Ben Warley, all guys who made it to the NBA. I was in a sheltered atmosphere of no responsibility and in the limelight. I was aware—and I am sure the other guys were also aware—of the special category we were in. We were special students, and we all took advantage of the situation. All of that ended after I had been playing pro ball for two years.”

Barnett was more fortunate than many other athletes who never make the transition from college to pro ball without drastically changing their lives. “Oh, it was a change,” insisted Dick. “I realized the world was going to go on without me, and that nobody is indispensable. We found that out when they traded Wilt and Oscar. If they traded them, they can do the same to anyone. That is one of the reasons there is so little allegiance in this league. You can be here today and gone tomorrow.

“You find out life isn’t just a game and a ball. There are other responsibilities you must deal with as a man. Just like anyone else, you are confronted with situations that must be dealt with. These situations may not be as harsh to us as they are to the everyday Joe on the street, because we athletes live in a rather isolated world. So, the changes I made in my lifestyle were dictated by the world around me.”

****

Dick Barnett was born in Gary, Indiana and attended Gary-Roosevelt High School. He had terrible study habits that caught up with him when it was time to think about college. “Yeah, it was a tough situation. I guess everybody has heard the story a thousand times from Black athletes, but I came from a poor family in the Gary ghetto.

“My father worked as a laborer in the steel industry, and my grandmother lived with me, my sister and brother. I had a number of scholarships, but education wasn’t one of our things then, and I could only get into Tennessee State. If it hadn’t been for sports, I never would have gotten a college education. So I would have to say sports have been the major influence in my life. Everything I own, materially speaking, is a result of my involvement in sports.”

Today, Barnett lives a very unpretentious life in an apartment on Manhattan’s sprawling East Side. His home is comfortably decorated, reflecting the change that has come over the man in recent years. The Barnett of old would have had a Joe Namath-type apartment, a long flashy car, tremendous wardrobe, and would have been the life of the party at all the slick, jet-set happenings.

But none of these things are present in the life of Barnett, who ranks 17th among all-time professional basketball scorers with 14,180 points coming into the season. Instead, he has found a purpose in life that has put into perspective the fact that only seven players in NBA history have played more games than his 836, as the season started.

The contests that Dick takes for “real” deal with the life and problems confronting people in the Black ghettoes across the country. In order to understand more about these problems, Dick is working toward his doctorate in Public Administration at New York University.

“Black athletes have to become more involved. It’s nice for an athlete to make his money, retire, and live a soft life lying out on the lake. Don’t get me wrong. I like to go out and enjoy myself, but I think uninvolvement is the easy way out. As long as we have one Black child with a chance to get out of the ghetto, then we must coordinate our efforts and do whatever is necessary to help. I just don’t go along with the theory of retiring and taking it easy.”

Last summer, without fanfare, Barnett spent his time conducting basketball clinics and speaking to kids all over the city. The rest of the time he spent running to keep in condition and playing one-on-one games at a park close to his home.

He stayed away from the famed Rucker Pro Tournament, as he does not share the belief that the pros have an obligation to play in the tournament. “On that level of competition, I wouldn’t want to play,” insisted Dick. “We have too many games during the season for me to wear myself out up there trying to prove something.

“When pros go up there, they have to play against so many unproven players who think they can beat the world. I know if I go up there, my competitive instinct will make me play the best I can. You know how it is. Everybody wants to shoot down the gunfighter.

“The younger pros go up there for the rah-rah. I don’t need that at this stage. I try to approach the game as if I am going to an office to do my job. I am not concerned with the crowds. I call that superficial concern—they can have it.”

At 35 years of age, Barnett doesn’t have much time left in the game. It has been only in the past four years that he has really made decent money, and he hates to give it up so soon.

How long can he keep going?

“Only about five more years,” said Dick. “I am in good physical condition and don’t feel like I am 35. I like to play all the year round. I am never really away from the game that long. I don’t drink or smoke, so perhaps those could be the reasons I have been able to play for 13 years. I take the position that as long as I perform credibly, my age doesn’t matter. Management wouldn’t let me stay here if I wasn’t doing my job.”

Said Red Holzman: “I see guys 20 years old who play like they are 40. Age doesn’t mean anything. If he is 35 and can play like this, he can play for me any day. Head-to-head, he is one of the best defensive guards in the league.”

A rumor circulating around New York is that Barnett is being groomed for the coach’s job when Holzman gets enough and wants only the general manager’s slot. Barnett has heard the rumors, but is noncommittal when asked about it. On days the team works out, it is often Barnett who takes them through their paces.

“I hear that rumor, but that’s just what it is,” laughed Dick. “I see that if and when the opportunity presents itself, I will make certain decisions. You know, a coach lives a precarious existence in the NBA. I can’t say that I would enjoy coaching; but at this point, I feel that I am well qualified.

“You don’t stay in this league for 13 years and learn nothing. I will say that if the coaching job was offered to me tomorrow, I would take it under certain circumstances.”

****

Dick Barnett is a fascinating individual, and one you could spend hours talking to about almost any topic. He is a well-read individual, aware of everything that is happening in this country as well as abroad, and his thoughts on some of the major issues around the country are well worth listening to.

“In my day,” said Barnett, “the vice was wine, which is not quite as detrimental as drugs. One mistake I think this country is making is sending people to prison for using marijuana and classifying it as heroin. It has been proven that marijuana is not addictive, but it could be the next step. This is where education comes into play. With the right education, a person 18, 19, or 20 could make a decision and stand by it. You can’t expect this from 11, 12, and 13-year-old youngsters, who are not being properly educated.

“Of course, living in a miserable ghetto situation, people are subject to reach out to anything. I think we have to change our approach to drugs. Perhaps we could experiment with the system used in England, where they give free drugs.

“The state and federal governments aren’t doing enough. But one good thing I recognized was Congress’ reluctance to sign the foreign-aid bill helping countries that contribute to our drug problem. I think it is good that they are scrutinizing things and questioning where our money is going, and whether it is accomplishing anything.”

Dick Barnett prefers to talk about relevant things. As he puts it, “What else can I say about basketball after 13 years? Some television people wanted me to appear on their shows and talk about basketball. I told them if basketball was all they wanted me to talk about, then I couldn’t appear on their programs. I am much broader than that.”

As an example of what he feels, Dick agrees that there is a stigma attached to the Black athlete. “I get so tired of Dick Cavett and Johnny Carson on those late-night shows. I’ve seen Willis and Clyde on those shows, and all they talk about is basketball and how many they scored. Who gives a damn?

“Why don’t they ask them what they think about East Pakistan and the position America took. This is only one of the pertinent questions needing answers. It has been proven that Black athletes have other talents besides athletics, but this is what you get on those programs. It takes a good show to bring out those touchy subjects.

“They are afraid of the Black-White issue, and they try to smooth things out by talking about basketball. It’s a good escape, these days. This is a Black magazine, and If all you wanted to talk to me about is basketball, I wouldn’t have wanted to do the story. That’s the way I feel.”

Dick Barnett has a lot on his mind, “but who’s going to listen to me?” he asked. “I look around the league and see Black guys and wonder how many coaching or administrative jobs are awaiting them when their playing days are over. I have to admit that basketball is leading the way in the hiring of Blacks in these capacities, but still, we have only one Black administrator in a team’s front office, and that is Wayne Embry with Milwaukee. Simon Gourdine is in the Commissioner’s office, but we still have a long way to go.”

As you read this, you must be wondering how relevant or irrelevant Dick Barnett is. Dean Meminger, the Knicks’ number one draft choice and a New York City product, give us a little more insight on the man. “On and off the court, Dick is the symbol of manhood,” states Dean. “He has priorities and values in life, which he honors. He is a very relevant figure in the community, but he doesn’t say that much on the court.

“He has helped me, but not to the point where I can take his job. He told me, ‘Youth should be preserved,’ but not at his expense. He’s very realistic, and I can deal with a guy like that. As far as I am concerned, he is a super individual.”

Clyde Frazier, who spent many nights on the hardwood with Dick, stated, “He’s always cool, man. Never gets excited and is a great clutch player. Maybe because he is so nonchalant, people tend to underrate him. He has made my job of running the ball easier, because he now guards the toughest guards. This enables me to rest more. Off the court, I don’t know too much about him because he is a family man and, well, you know me.”

About himself, Dick Barnett said, “If all the great players who come through the league were as great as people say they are, perhaps I wouldn’t be here today. I am secure in the knowledge that I am. I have paid my dues in terms of going out and sacrificing and doing whatever is necessary to develop my talents.

“I feel that I am a great ballplayer, one of the greatest to ever play this game. But whether the public relations people want to give me credit is another thing. My record speaks for itself.”