[This is a long story about Mitch Kupchak coming off the bench for the Washington Bullets. Out of respect for your reading time, I’ll keep the intro barebones and brief. The story that follows appeared in the March 1979 issue of SPORT Magazine, and the byline belongs to Mark Ribowsky, who has gone on to write many outstanding books on sports and music.]

****

A few minutes after the Washington Bullets decimate the Milwaukee Bucks on this mid-November night, a man named Dolph Sand, wearing a sport jacket with “Capital Centre” stitched on it, is running around the Bullets’ locker room looking for a body to take out to the court for the Star-of-the-Game Show, a brief player interview staged for the remaining fans in the arena. After approaching the first few players and getting no takers, Sand walks over to Mitch Kupchak, the ebullient, galvanic, 6-foot-10 backup center-forward, who is sitting at his locker holding an ice pack on his right calf.

Looking up at him, Kupchak breaks into laughter. “You gotta be kidding!” he squeals. “I think I just played the worst game of my life.”

Kupchak, averaging 16.2 points a game (despite averaging less playing time than five other Bullets), had scored only 11 in the club’s 138-111 pillaging of the Bucks. Eight of those points had come in the last quarter when both clubs were trying to stay awake waiting for the one-sided game to end. More tellingly, Kupchak had turned the ball over the first four times he’d touched it. He had also made some defensive errors.

When Sand says all that doesn’t matter, Kupchak shrugs and asked him, “How much you giving away this year for those interviews?” Feverishly checking his watch, the guy says it’s $25. Kupchak mulls it over.

“Okay, let’s go. I could use it to pay for a wide-angle camera lens I’ve had my eye on.”

The man then leads Kupchak onto the court, and when his name is announced, the slowly exiting crowd gives him a rousing cheer. As Kupchak is being interviewed at center court, Sand says, “He’s the only guy in the room who could have come out here after a lousy game and gotten that reaction.”

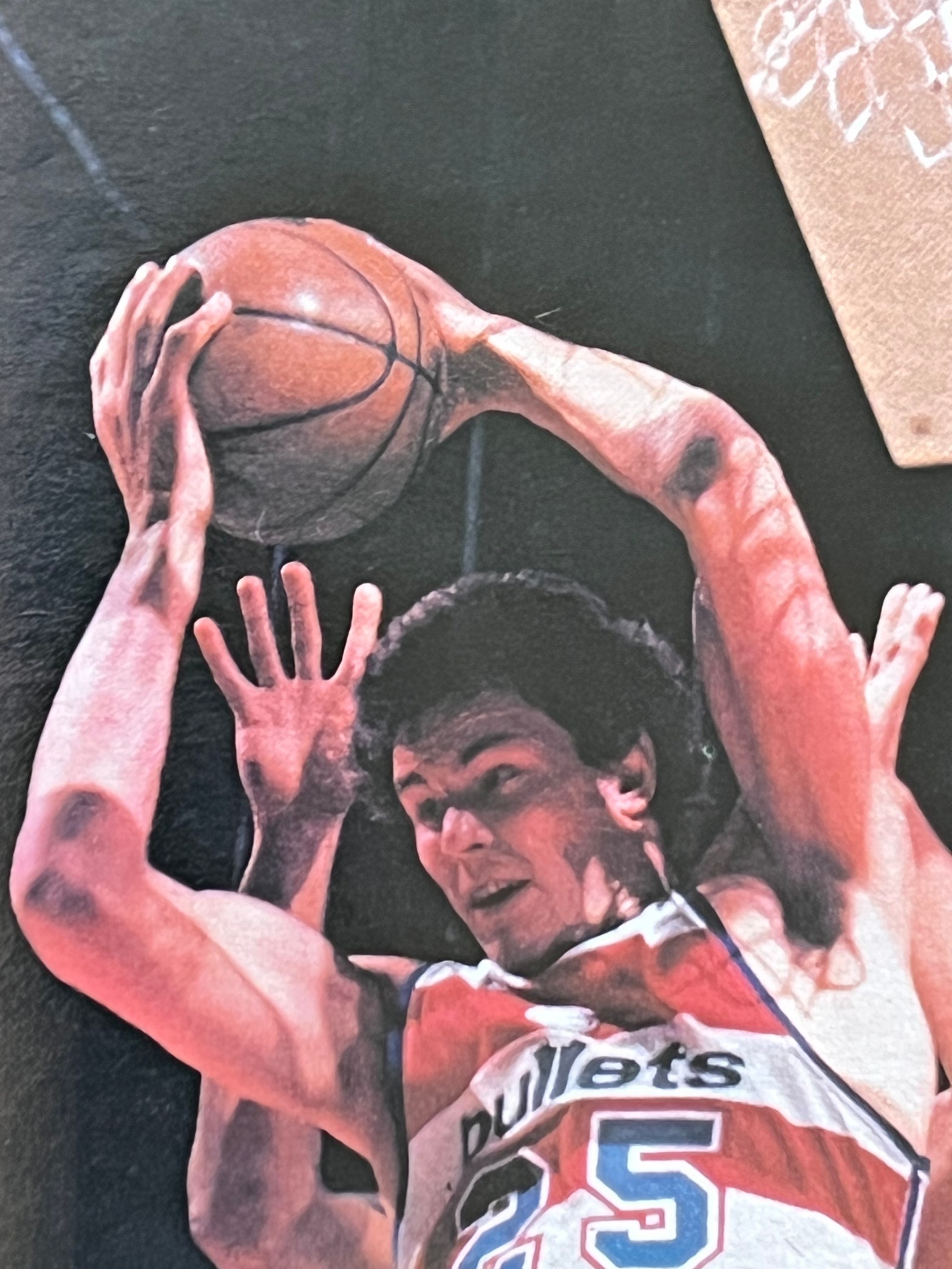

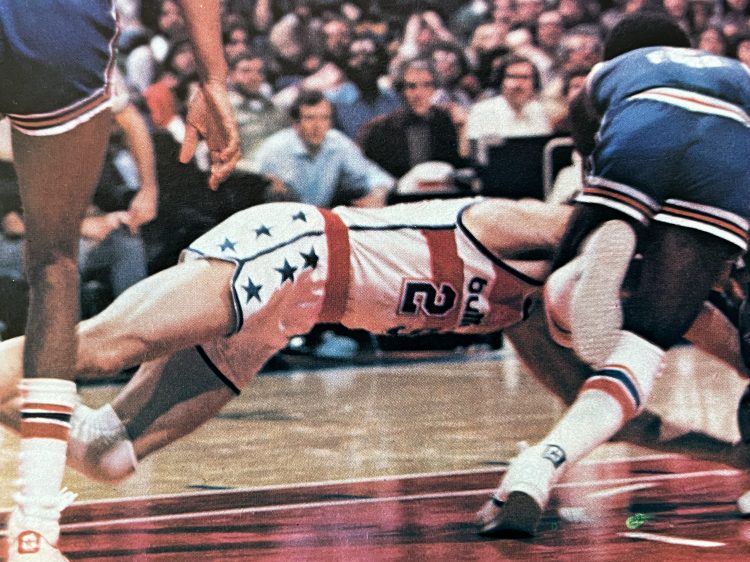

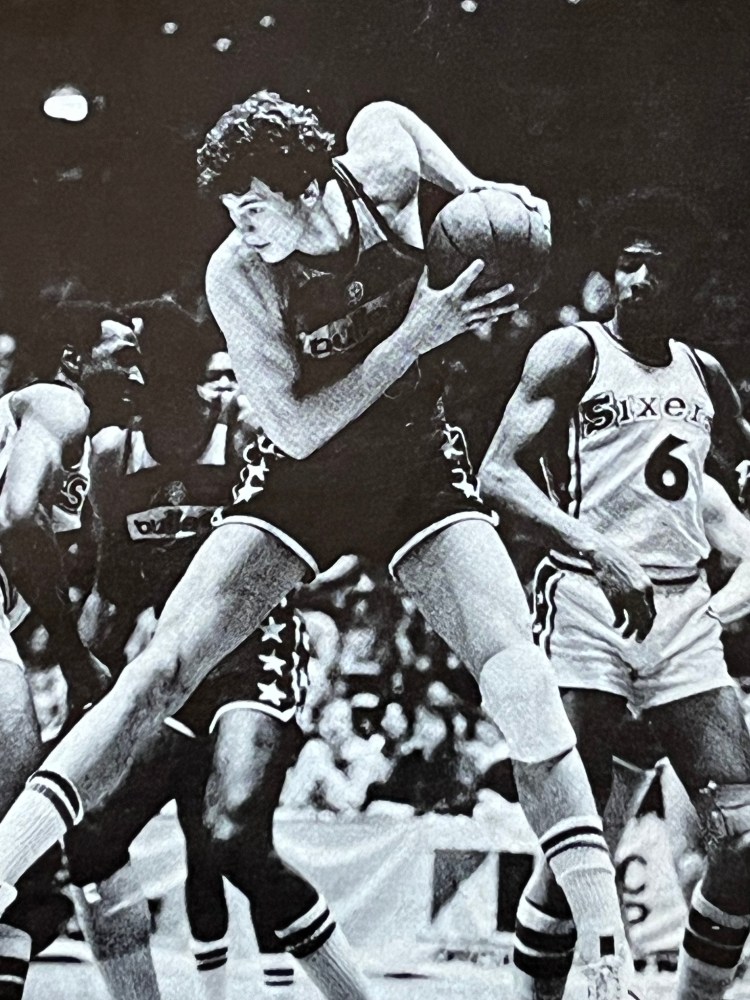

The reaction would seem to be a logical byproduct of the way Kupchak plays the game. The 24-year-old Kupchak’s vitality, impetuosity, and fire on the court have produced a kind of incandescent glow among Bullet fans—and among many members of the Bullet team that in late November seemed primed for a second-straight National Basketball Association championship. Big, strong, fast, and occasionally rabid in his intensity—in one game during his rookie year, he dove after loose balls 14 times—Kupchak, a sure starter on most other teams, backs up all three frontline positions on the Bullets.

Counted on heavily to light a fuse under the team when he goes in, Kupchak’s value is magnified by the fact that he goes in whenever center Wes Unseld, power forward Elvin Hayes, or small forward Bobby Dandridge go out. Kupchak is, most experts maintain, the best sixth man in the NBA.

Kupchak has electrified the league ever since his first game two years ago. As a rookie, he played all 82 games, averaged 10.4 points per game, scoring on 57 percent of his shots from the floor (the best mark by a rookie in NBA history). In the playoffs, he averaged 16.2 points per game, while hitting on 59 percent of his shots.

Last season, he averaged 15.9 points per game, even though he missed 15 games after tearing ligaments in his right thumb in January. But he came back from surgery to be a critical force in the championship playoff drive: He started three games against the Philadelphia 76ers when Unseld was hurt. Then, with the Bullets down three games to two against the Seattle SuperSonics, he shot 7 for 10 and scored 19 points to help knot the series, and went 5 for 7, scored 20 points and made the key offensive move—a three-point play with only 90 seconds left—in the title clincher.

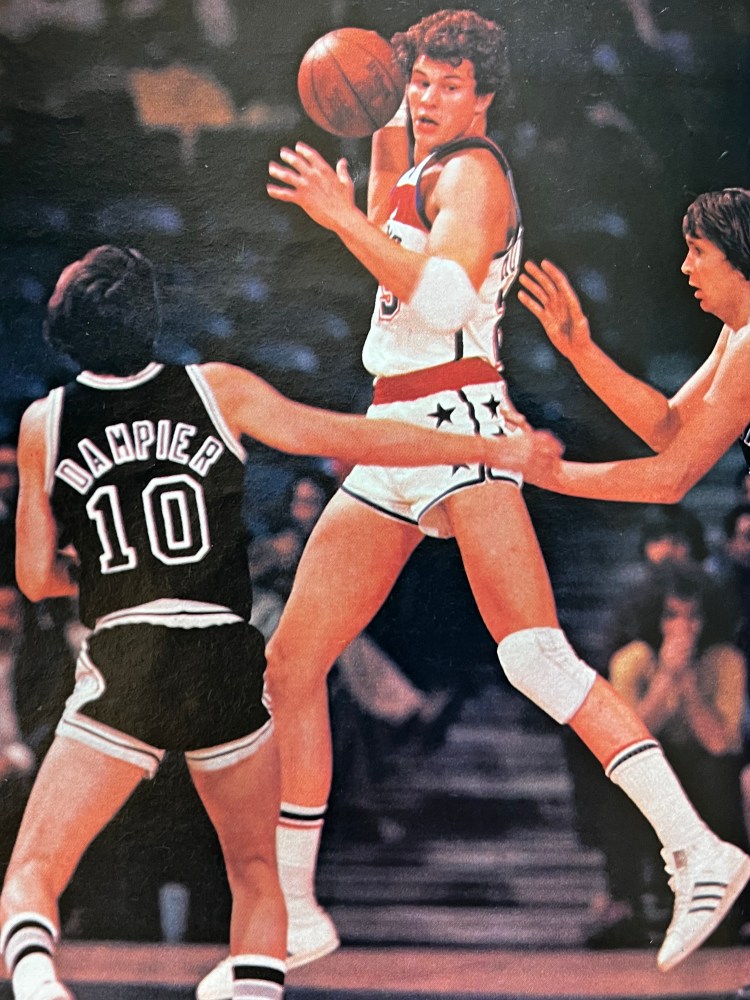

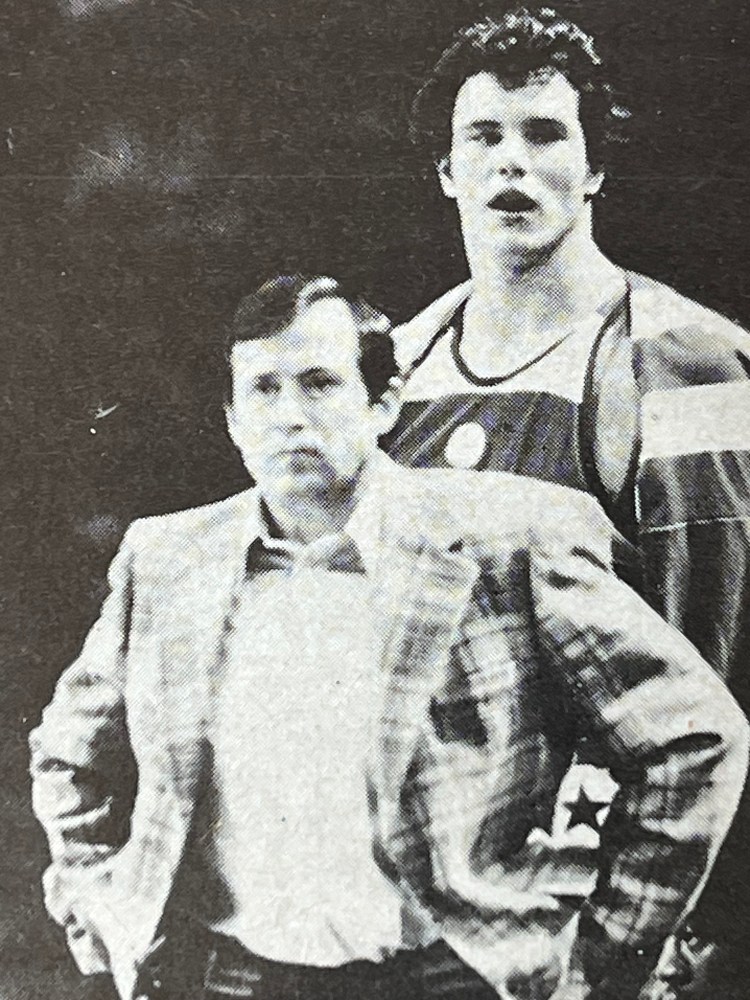

Because Kupchak is so versatile, he poses monumental problems for opposing teams. “He creates favorable mismatches for us,” says Bullet coach Dick Motta, who likes to compare Kupchak with Jerry Sloan, the hellaciously tough guard Motta coached with the Chicago Bulls some years ago. “Because we use Mitch at different spots, teams don’t know how to gear their defenses. He confuses the hell out of them.”

Indeed, in this game against the Bucks, Kupchak had been matched against every Milwaukee forward and center, and although he had a rare off-game, he was the source of constant bewilderment to the Bucks’ defense. Finally, they simply threw up their hands and let 6-foot-6 Ernie Grunfeld try to guard Kupchak—who hit four straight baskets on inside moves. Kupchak also started several fastbreaks with rebounds, then led everyone upcourt to score on layups.

In the game before this one, Kupchak demonstrated his versatility against the Cleveland Cavaliers’ 6-foot-11 Jim Chones by popping in five baskets on soft outside jumpers, a skill he rarely had to utilize as an All-America center at North Carolina. In those days, his game consisted mainly of standing near the basket, waiting for Phil Ford or John Kuester to give him the ball for layups. “He’s much more well-rounded now,” Motta says. “He’s worked like a dog on his shooting and offensive rebounding. Now, there’s nothing he doesn’t think he can do.”

As Motta knows—and often confirms with his piercing voice during games—there are still a few aspects of Kupchak’s game that need work . . . such as defense and passing. But, as it is, he’s probably as good a defensive player as Dandridge and a far better passer than Hayes, who often regards that phase of the game as a mortal sin. Says Motta: “Aside from shooting, Mitch doesn’t have all the natural talent in the world. But what he does have he makes better with his hustle and desire, like Sloan did.” Or, as Dandridge says, “He’s the only 6-10 White guy I know that plays like a 6-1 Black guy.” But maybe the best thing about Kupchak is that after three years, he can still accept a limited backup role without bitching about it. At least for now.

****

In the locker room again, the other Bullets get on Kupchak’s case about his performance, but he just laughs as he peels off his uniform. “Hey, Mitch, a guy was just in here looking for you,” kids slinky guard Larry Wright. “He was from a brick company . . . he said he wanted your shot.”

“I heard he was from the cesspool and wanted to make a deposit,” Elvin Hayes announces.

Sitting next to Hayes, Wes Unseld removes a knee pad and playfully shakes his head. “We were taking bets on when you’d handle the ball without throwing it away,” he tells Kupchak, “and nobody won.”

Ballhandling guard Tom Henderson walks in from the trainer’s room and says as he passes Kupchak: “They made a law in New York that you have to pick up what you dropped tonight, man.”

Finally, Kupchak sits down at his locker and replaces the ice pack on his calf—where a black-and-blue mark has been raised, the newest addition to a body covered with assorted contusions as the result of his close encounters with wooden floors. A long, faded scar cuts around the corner of his right eye. “When I was six, I slid down a banister and crashed into a glass coffee table,” he explains. “They took six stitches, but I don’t even think I cried, even with blood running all over the place.” A grin. “I was always made of solid steel.”

The voice is high-pitched, the words rushed. The New York accent—he grew up in Brentwood, Long Island—is unaltered by his four years in the South. The body is not solid steel, but Kupchak did put on a few pounds last summer through weight lifting (he’s up to 235) and his thick arms and legs bear no resemblance to the pipe cleaners that stuck out from his body at Carolina.

I ask if he has any explanation for the game he played tonight. Another laugh. “I think the problem was that they sent me in during the first quarter. Usually, I don’t get in until the second. I wasn’t ready to go in, so blame it on the coach, not me. Honestly, though, I have enough confidence in myself to know it was just one of those games you laugh off.”

As Kupchak goes to shower, Henderson, smiling widely, says to him: “I’m telling you, you better go out there and pick it up.” Walking over to Henderson, I ask if the rest of the Bullets are as easy to ride as Kupchak. He rolls his eyes. “Let me tell you, man, there are a lot of guys in here you don’t say anything to if they play bad. That’s why Kup is so good for our collective head, he’s always on a high. . . Hell, everybody likes Kup. Like the Black players, they get along with him very well. Kup likes to talk that jive, but he don’t sound phony, he sounds real.

“That’s funny, too. Because two years ago, he was kind of a loner. He’d be in a trance after bad games. I’d have to tell him, ‘It’ll be all right, big guy.’ I think the way he played in the playoffs last year made him feel he was important. I think he still gets down, like about not starting. But he can deal with it—on the surface.”

Kevin Grevey, the star of the game tonight with 24 points, has just finished talking with the press. Grevey, who two years ago shared an apartment with Kupchak (until Mitch bought a four-bedroom, $150,000 home in Gambrills, Mary.) is considered Kupchak’s closest friend on the club. The hot-shooting guard laughs when I ask about Kupchak.

“We had a tremendous rivalry in college [Grevey went to Kentucky], and I just hated the guy. Here, he was still the enemy to me at first, so it took a while to really know him. He was awfully quiet, and I thought he was naïve, immature. Then he started tagging along with me when I went out to bars. It really opened him up. Last year he was partying every night, going out with a lot of women.” A giggle. “Now, he lives life like he plays ball—in a hurry and a little reckless. Underneath, he’s still a naïve kid, but he’s learned to deal with people, and it’s helped his confidence. It shows in his game, too. He used to be awkward, unsure.”

I ask if Kupchak is bugged by not being able to start. “Yep, no question,” Grevey says. “It bugs me, too—not that he doesn’t start, but that he’s not getting more time. He should be getting at least 10 minutes at all three positions up there.” Kupchak was averaging only about 25 minutes a game. Grevey shakes his head. “I tell you, if things don’t improve in that area in a year or so, I wouldn’t blame him if he plays out his contract and leaves.”

Several other players in the room also felt that Kupchak should be playing more, but then recognize his dilemma: being in the same box score with Unseld, Hayes, and Dandridge. “We know how tough it is for Mitch,” Grevey says, “and we really appreciate that. He doesn’t cause problems by complaining about it.”

Sometimes, however, others do it for him. After the first playoff loss to Seattle last year, both Hayes and Dandridge suggested that Kupchak start in place of Unseld, whose aching knees and lack of scoring contrasted markedly with Kupchak’s quickness and shooting touch. Had Unseld not rallied to lead the Bullets to the title with his rebounding and defense, it would have been the cause celebre of the series. As some Bullets muse, Kupchak’s presence may even have provoked Unseld’s remarkable recuperation. Motta hints at that when he says, “Having Mitch in the wings is the best motivation I know for those other three up front.”

The 32-year-old Unseld will only say, “I feel no heat from Mitch; he’s good for me. I can get my breath, not knock myself out for 48 minutes as in the past.” But another Bullet says, “Wes is doing some squirming on the bench when he’s been sitting lately.” Indeed, last season, Unseld averaged the fewest minutes-per-game (33) since his injury-riddled 1973-74 season, when he played 56 games, and this year he is averaging 31. Similarly, the playing time for both Hayes and Dandridge has gone down as Kupchak’s has gone up.

****

When Kupchak returns from the shower, I ask if he’s satisfied with the minutes he’s now getting. “I don’t know . . . it’s hard to say,” he begins, lowering his voice. “I can understand why I don’t get more time, but . . . Wait. I want to say first that I am satisfied I’m not a second-stringer just because I don’t start. I know that Motta wants to look down the bench and see me first. I’m kind of a luxury to the club. I feel important. But, no, I’m not content with my role. I don’t think I’ll ever be satisfied unless I’m playing 40 minutes. I’ve gotten where I am by working at it, so to have to be, uh . . . confined, in a way, is difficult. I want to be depended on, not hoped on, not to have to produce right away or be taken right out.”

He lifts his head and shrugs. “But I can accept it. It’s an abnormal situation in that Wes and Elvin and Bobby D. are better than me. I often look at it from that perspective, and over the perspective of my whole life, and it doesn’t matter as much. I’m in the NBA. I’m healthy, my parents are healthy. I’m very lucky.”

Listening to Kupchak, I remember that a Washington writer had called him “dumb.” Now I realize the guy couldn’t have spent much time with Kupchak or asked him anything requiring a thoughtful answer. Kupchak is an easy caricature because of his fervid play. But he’s rarely out of control on the court, and he is no oaf off it.

A political science and psychology student at North Carolina, Kupchak’s sensitivity is made clear by the way he speaks of his offseason trip to Israel (“The most awesome experience of my life.”) and the way he reacted when he was fined a total of $1,750 for a fight he had with the Knicks’ Lonnie Shelton last year. “It messed up my head and my game for a while,” he says. “Being fined all that money [as was Shelton] for defending myself, it ate at me. I was worried people would think it meant I was sadistic rather than aggressive.” As he speaks, there is a vulnerability in Kupchak’s face that you never see on the court.

Now when I ask Kupchak whether he’s thought about playing out his contract (one year plus two option years left) and going elsewhere, he says, “I’m not gonna talk about it, no reason to yet. I like it here, we have something good going. That’s what I want to think about.” He thinks about it a moment. “Motta has told me that as long as he’s here, I’m gonna get more of a role. He’s never lied to me.”

I tell him that I thought Motta had singled him out for heated instructions whenever the Bucks brought the ball down the court, yelling such things as: “Mitch! Close down the lane!” Kupchak’s grin returns. “I was yelling at myself . . . Motta’s been doing a lot of yelling at me lately, though. I take that to mean he’s taking a greater interest in me.”

Kupchak slips into a pair of baggy, blue corduroy pants, a white knit shirt, leather bomber jacket, and scuffed-up loafers—with no socks. “Never wear ‘em,” he says. “I like to feel comfortable. I don’t even own a suit.” Hearing that Grevey shouts from across the room, “You think he dresses bad now? You should’ve seen him two years ago. This is Pierre Cardin by comparison.”

Sitting next to Kupchak’s locker, reserve guard Charles Johnson shakes his head as he sips a can of beer and says, “Man, how can you wear that?” Kupchak feigns anger and tells Johnson that his own outfit—jeans and a T-shirt—isn’t exactly high fashion. “Listen here, Kupcake,” Johnson shouts back, “to put me in your clothes would be like putting a Bengal tiger in a chimpanzee suit.”

Kupchak laughs, then stuffs cans of beer into his bag and exits, saying, “If anyone finds any stat sheets of tonight’s game—burn ‘em.” Down the corridor, Kupchak meets the Bucks’ Ernie Grunfeld and Quinn Buckner, teammates of his on the 1976 U.S. Olympic team, whom he takes out on the town whenever the Bucks come in. Grunfeld tells Kupchak he’s got a lift from Grevey tonight and will meet him downtown, and Kupchak, Buckner, and I walk to the parking lot, where Kupchak finds a carnation and a letter on the windshield of his gray Monte Carlo. “I’ll read it later,” he says, as we pile Into the car, which is littered with newspapers and empty beer cans. Kupchak then heads for the Georgetown nightclub area.

“You wanna go have a few drinks?” he asks a weary Buckner, who slumps in his seat in despair—the Bucks have lost four of the last five games.

Buckner says, “No, I wanna go have a whole lot of drinks.”

I ask Buckner about living with Kupchak in Montreal during the Olympics, and he smiles. “Mitch here was a quick learner . . . a little slow at first, but after we won the gold medal, we both went out to . . . what was that place?”

“Sir Walter’s . . . a good place to tear off some fun,” Kupchak says.

“A sweet place! We didn’t get back until 10 in the morning. Everyone else had already packed up and gone home, and we were just getting’ in.” He looks at Kupchak. “That was something else that night, wasn’t it?” Kupchak’s answer is a broad smile.

****

As the car races down the Capital Beltway, Kupchak and Buckner get into a discussion of whether technical foul fines are tax deductible—both men get more than their share of them—and Kupchak says through a grin: “That’s why I got into that fight with Shelton. I needed a write off.”

After a half-hour drive, Kupchak parks in front of a singles place called The Foundry. Inside, a pretty fair former Atlantic Coast Conference-Southeastern Conference all-star team sits at the bar with glasses in hand. The Bucks’ Brian Winters catches up on old times with Kevin Joyce, his former backcourt mate at South Carolina and now an assistant coach at the school, as Grunfeld (from the University of Tennessee) and Grevey check out the house. Kupchak pulls up a stool and orders a round of Heineken for the party as a pretty brunette says, “Remember me, Mitch? Remember that night last year?” Another huge smile says he does.

A sandy-haired man sitting next to Grevey introduces himself as Russ Foster and says he also lived with Kupchak and Grevey. “Mitch is a really beautiful guy,” he says. “He’d do anything for you. One time, Kevin had to cancel out on a Cancer Fund banquet that I put together in South Carolina, and Mitch said he’d come for him. I didn’t think he would, because it was on a Monday morning following a Sunday night game, and it was such short notice. But he left right after the game and drove all night to get there. His word is gold.”

Ernie Grunfeld leans in. “Listen,” he tells me. “Mitch is probably the most-liked guy in the league, because he’s so dedicated. I remember Montreal, he was running laps by himself while everyone else was sleeping. The Bullets don’t know what they’re missing not using him 40 minutes. Jesus, I wish we had him.”

After two hours, Kupchak, Buckner, Grunfeld, and I get into Kupchak’s car and drive to another part of town. Kupchak parks on a side street, and we walk a few blocks toward another singles spot when we pass a noisy, crowded bar. Seeing three scantily dressed blondes jiggling on the counter as they’re sprayed with seltzer water, Grunfeld says, “They’re having a wet T-shirt contest in there. Let’s go.”

Once inside, Kupchak bets Grunfeld a beer on who the winner will be . . . and loses. “Ah, they just gave it to the one with the most showing,” he sneers as we leave. “Hell, in Ft. Lauderdale, they don’t wear anything. That’s the way the contest should be.

The next stop is a bar called Paul Mauls, where Kupchak spots an old friend—“a former Miss Maryland,” he calls her. But when the place closes as 2 a.m., Kupchak ambles out into the now-freezing morning with a semi-attractive brunette hanging on his arm. He makes it clear, in a nice way, that he doesn’t want the girl to go any farther with him, but she forces him to kiss her good night.

Afterward, as we are en route back to Washington, Kupchak hits a bump in the road, and we hear a whining noise from under the car. “I can get rid of that noise,” Kupchak says. He opens the windows and turns the car stereo up full blast.

****

At noon the next day, a groggy, gaunt-looking Kupchak sits in a Howard Johnson’s restaurant near the Capital Centre sipping some chicken soup. “We had an optional practice at 11 in the morning today,” he says. “No way I could make it after last night.” He looks a little disturbed about something. “Listen, I don’t want you to get the wrong impression from last night. If we had a game or practice today, it wouldn’t have been like that. I’m not irresponsible. I just enjoy a good time now and then. You don’t get to have a lot of them during the season.”

As Kupchak finishes his soup and starts on a club sandwich, I wonder aloud if it’s gotten harder for him to keep stoking his renowned enthusiasm after two years. “Definitely,” he says. “It’s getting harder and harder. But I’m fortunate in that I’ve always played with a certain aggressiveness that goes back to my childhood.

“I played a lot of playground ball, where you never waited for whistles, because there was no such thing as a foul; you just kept going, moving, running. I also played with a lot of Black kids, so I developed a certain style, the challenge aspect, having to play for respect. Being on the team meant you gave it all you had. I remember going to Knick games in the Garden and seeing Walt Frazier sitting by himself and not getting in the huddle during timeouts, and it really disgusted me. I hate a dead bench. If I paid nine bucks for a seat, I’d be mad not seen guys play with emotion.”

Kupchak—“It’s Ukrainian, my grandparents on both sides of the family came from the Ukraine before the Russians swallowed it up”—was born in Hicksville, N. Y., the first son of a construction inspector and his wife, who moved to nearby Brentwood six years later.

His first love was baseball—he’s still a rabid Yankees fan with a store of trivia questions about the team—until, he says, “the strike zone got too big,” the result of him growing four inches to a bony 6-foot-5 and 140 pounds in the ninth grade. It was then that the high school’s basketball coach Stan Kellner, “pulled me right out of the hall one day and made me do things I didn’t want to do, like dribbling. For a while, all I did was trip over my feet.”

But by his senior year, he was an all-county center and a 6-foot-9 plum for college recruiters. “I’d decided to go to Notre Dame, then changed my mind. I don’t know why, really, I just decided I’d rather play in the ACC.” The choice came down to Virginia and North Carolina. Why, Carolina? “I don’t know, I just liked [coach] Dean Smith, because he never promised me anything. He told me the truth, that I’d have to sit a while before being a star. I also liked the players, they hung out together, had that togetherness.”

Kupchak credits one of those players, Bobby Jones [now with the Philadelphia 76ers], with making his game bloom: “He changed my head about playing center. I grew up watching Wilt and Kareem on television, and I thought I could play their game . . . you know, holding the ball over my head while the traffic cleared, then jamming it. Bobby showed me that a big man could be versatile—that I could run, pass, help out on defense. Plus, he had a heart problem and is mildly epileptic, and seeing him play like he did made me want to work that much harder.”

Of Coach Smith, Kupchak says: “It always amazed me how he could manipulate us, make us fear him even though he never once used a cuss word: the hardest thing I ever heard him say was, ‘Gosh darn it.’ He was a tough S.O.B. and sometimes very cold—especially to freshmen and sophomores—but when I had a back operation [for a slipped disc] after my junior year. I’ll never forget Dean walking into the operating room in a surgical mask and gown. I understand he watched them cut into me. Later, I had convulsions, and Dean kind of turned away to keep from seeing it, but he was there all the way, and that meant a hell of a lot to me.”

Now, Kupchak and Smith talk often. “He recommends lawyers to help me with my finances. Dean’s very persuasive. So far, I’ve hired three lawyers, and I’m not even making that much.”

Kupchak did sit at Carolina for two years. Given the starting center spot in his junior year, he made All-America. But then came the back operation. As a senior, he says, “I thought I was terrible. I’d gone from 235 to 215 because of the inactivity. In a way, though, it helped my mental development trying to do it on guts alone.”

Kupchak underestimates his senior year. He was the ACC Player of the Year and an All-America, and if not for a bad game in the NCAA regionals against Alabama—Leon Douglas dominated him—he would have gone higher than the 13th pick on the first round of the NBA draft.

After his breakfast, Kupchak drives to the Capital Centre to tape, a commercial with Charles Johnson promoting a college basketball game to be played there. The commercial calls for Johnson to do a takeoff on the “You don’t have to call me Johnson” routine from the television commercial, but he balks at first. “Give him a few gin and tonics like they do on the plane,” Kupchak tells the director, “and he’ll do anything.” After two takes, Kupchak changes into a warmup suit and runs laps around the arena’s concourse for a half-hour. Then, after baking in the sauna with Johnson, he gets annoyed when Johnson tells me Kupchak sometimes goes for points at the expense of team play.

“Hell, if I don’t score, I come right out—and so do you,” Kupchak tells him. “Dandridge can get eight points and still get 40 minutes. I have to set off a spark. If I was starting, I might not get the points I do now—but I wouldn’t have to worry about it.” Johnson nods in agreement.

An hour later, Kupchak drives me to the airport. On the way, he runs a red light in full view of a cruising police car. “I got nerve, man,” Kupchak says, smiling.

****

Kupchak’s one-game slump comes to an emphatic end the next night against the Nets in Piscataway, N.J. This time, Motta sends him in for Unseld with 10:44 left in the second quarter. With the Bullets leading 44-28, Kupchak quickly grabs a pass from Grevey on the baseline and pumps in a 15-foot jumper. Two plays later, he flies ahead of the field, takes a lob from Johnson, and slams the ball home. After shooting an air ball, he curses himself during a timeout, his head popping up and down as he spits out the words. He then comes back on the floor and nearly takes a poke at Tim Bassett when the Nets’ forward hacks him on a drive. Kupchak adds four more free throws, and his eight first-half points help the red-hot Bullets soar to a 70-40 advantage.

Entering the game again, with two minutes to go in the third quarter, Kupchak gets more irked when, twice in a 30-second span, he’s called for playing an illegal zone defense. After the Nets hit the technical foul shots given to them for Kupchak’s violations, he rips down two offensive rebounds with a fury and converts both for baskets. He finishes with 21 points and eight rebounds in 23 minutes.

In the locker room afterward, however, Kupchak is more concerned with the two technicals than with his numbers: “The Nets play the zone, and I get the T’s. It stinks, man.” He looks at assistant coach Bernie Bickerstaff. “I look straight out at the ball—isn’t that the way I should do it?” Bickerstaff nods. “Don’t worry,” Kupchak says, “I will. I don’t give a crap what they [the referees] tell me.”

Twenty minutes later, Kupchak walks into the corridor and meets his parents, who have come from Long Island to see him. “You may not believe this,” Sonia Kupchak, a tall, smiling woman, tells me as her husband, Harry, a big, quiet man, chats with their son down the hall, “but when Mitch was six months old, he snatched a parakeet out of midair with his hand. The thing was pecking away at this hand, and Mitch was standing there in his crib laughing. He didn’t know he was scaring the bird to death.”

She laughs. “He didn’t always know why he was doing something, but he never hesitated to do it.” To this day, Mitch Kupchak seldom hesitates when he’s after something.