[No intro needed for Larry Bird. Except to say that this story ran in the April 1991 issue of Basketball Digest. At the keyboard and offering high praise is Robert Falkoff. His beat was the Houston Rockets, not the Celtics. In fact, Falkoff co-authored A Rocket at Heart with Rudy Tomjanovich. Falkoff chronicles Bird’s many Houston connections, which before reading this story, I would have never remembered.]

****

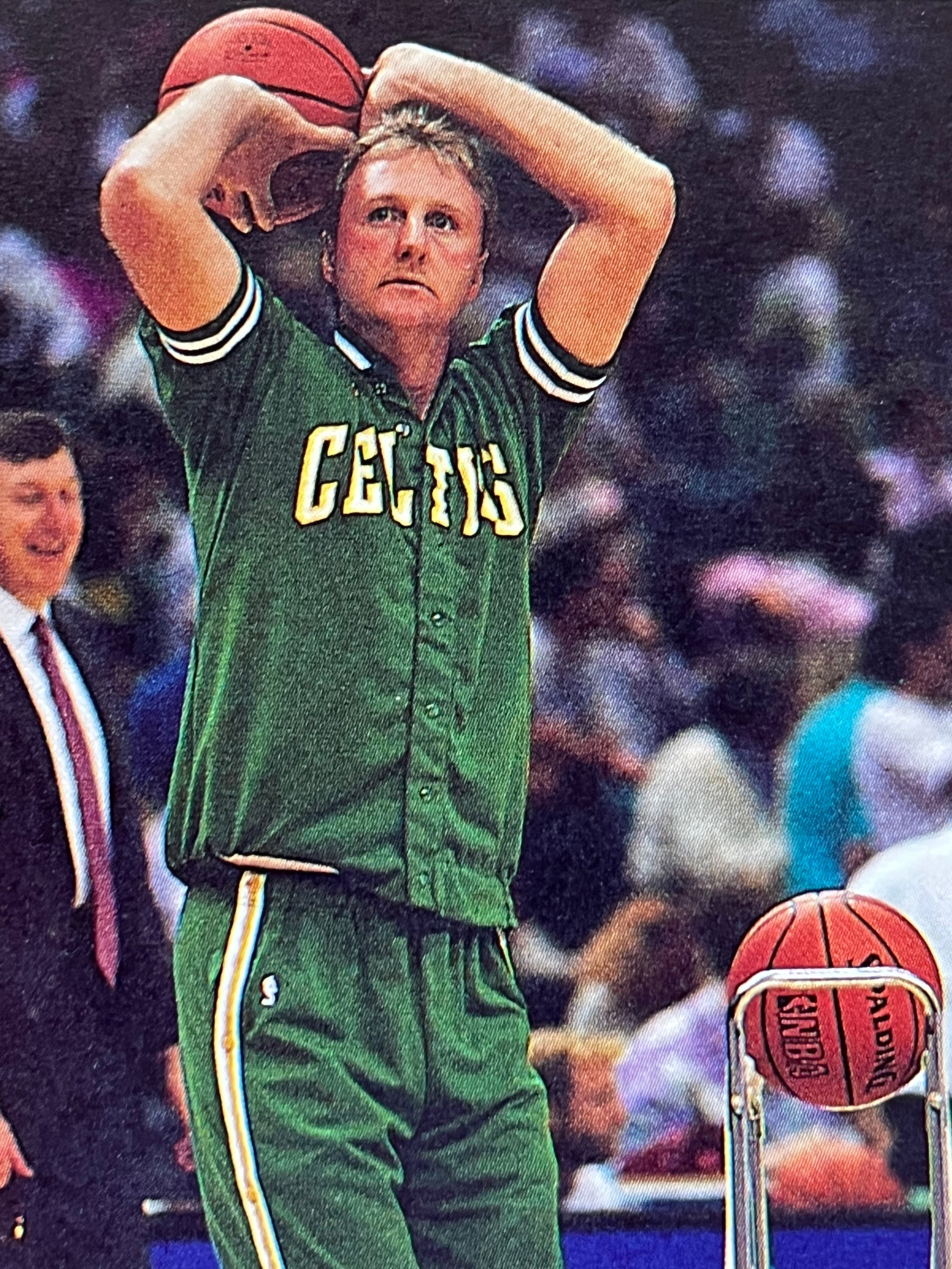

Okay, hoop aficionados, it’s time to conjure up images of an ideal forward. Let’s start with shooting touch: Who can bomb home feathery jumpers from three-point range and hit clutch free throws? Who can weave delicately through the lane, then scoop the ball into the basket with either hand? Bird’s the word.

The super forward must be able to pass, too. Who has the instincts, the court vision, and the fundamental skills to deliver the ball in style through a maze of startled defenders? Bird’s the word.

You want rebounding out of the forward? Try Larry Bird. He’ll also make the clutch steal, provide impeccable leadership, and generally turn the forward’s job into an art form.

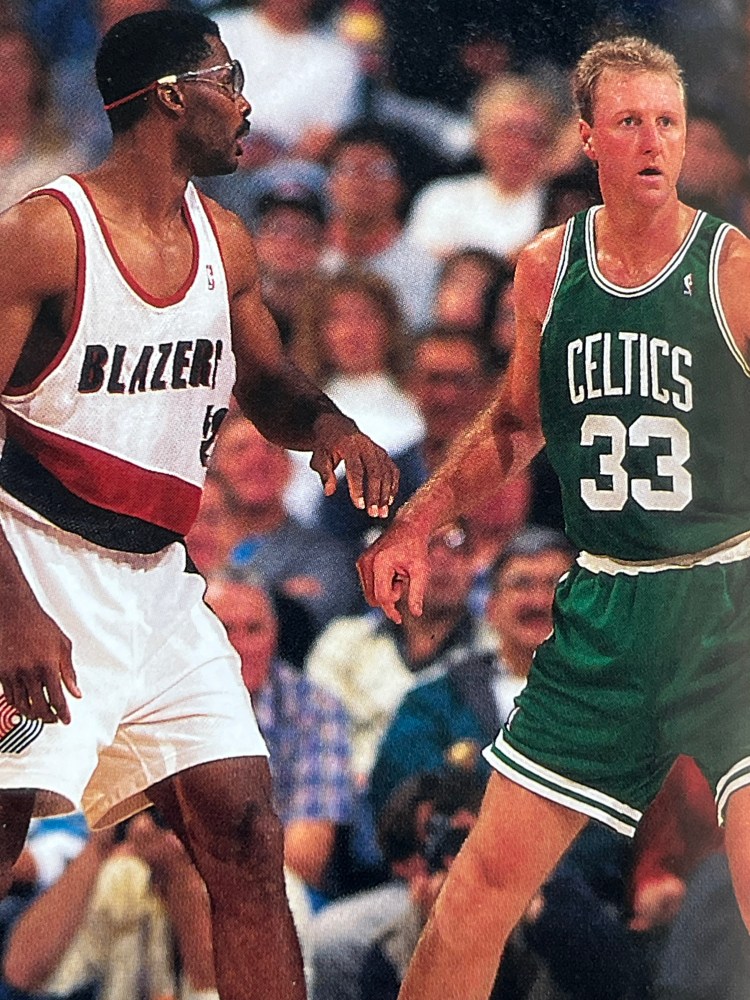

In his first 11 NBA seasons, Bird established the standard by which all players at the small forward position will be judged. He moved to the power forward spot this season and was enjoying his new vantage point before recurring back problems knocked him out of the lineup in early January. But regardless of how well he fares at his new position, Bird will be remembered as the game’s best swingman.

“When it’s all said and done, Larry will go down in history as the best at his position,” said Bill Fitch, former Boston Celtics head coach who helped usher in the Bird era 12 years ago.

Indeed, it has been a glorious ride for Bird, who has earned his spot on the Boston sports pedestal with revered athletic figures, such as Ted Williams, Carl Yastrzemski, Bobby Orr, Bill Russell, and Bob Cousy.

But Bird turned 34 in December, and one of the overriding issues heading into the 1990-91 season was whether the Celtics legend could fight off Father Time for a couple of more years. “There are five or six guys who I think are dominant players in this league,” Bird says. “And I’d say I’m about sixth or seventh. I don’t think I’ve dropped that much.”

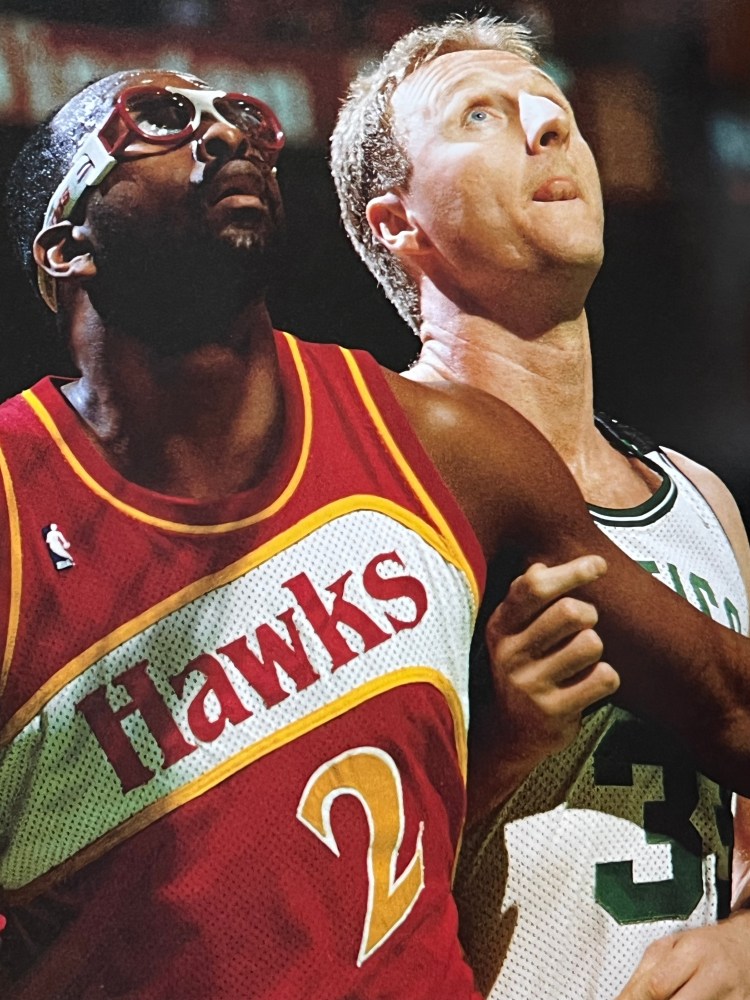

Bird’s list of blue-chippers starts with guards, Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan. Even if you throw in Barkley and Karl Malone—plus the celebrated center trio of Hakeem Olajuwon, Patrick Ewing, and David Robinson—there’s plenty of room for Bird in the penthouse of superstars. Nevertheless, Bird had a bittersweet 1989-90 season, and now that he is shouldering less of the load in Boston, it is time to ponder whether this Bird has gradually begun a downward flight pattern that will signal the end of an era.

After missing virtually the entire 1988-89 season because of double heel surgery, Bird shot just .457 in the first half of his comeback year. He also had some philosophical differences with then-head coach Jimmy Rodgers. Rodgers wanted Bird to play fewer minutes, but Bird wanted to be on the court. Rodgers wanted Bird to distribute the basketball, but Bird wanted to be the “go-to” guy. Rodgers also wanted to set up and call plays, but Bird preferred to see more running.

Early in the season, some unnamed Celtics pointed to Bird as a negative influence, and there were even a couple of editorials written later in the year that argued that trading Bird would be in the Celtics’ best interest. Bird didn’t agree and seemed to be stung by the suggestion. “Are you kidding? No.” Bird said, when asked if the Celtics would trade him. “But if Wayne Gretzky could be traded, anything could happen.”

Bird came back strong in the second half of the season, averaging 26.6 points, 10.5 rebounds, and 7.3 assists. By comparison, he had averaged 29.9 points, 9.3 rebounds, and 7.5 assists in 1987-88, his last full season.

The Celtics got off to a roaring start in last year’s playoffs, thrashing New York in the opening two games of their best-of-five series. But when Bird missed a potential game-tying three-pointer in the waning seconds of Game 3, the Knicks tightened the series at 2-1, setting the stage for the Celtics’ collapse.

New York wound up winning Game 5 in Boston Garden, and Rodgers lost his job a couple of days later. Suddenly, there were new batches of material about the “aging Celtics” and a string of question marks alongside Bird’s name. “All I know is when I wake up tomorrow, I’ll be in shock,” Bird said after the decisive loss to the Knicks.

Bob Ryan, the Boston Globe columnist and longtime Celtic observer, offered some advice following Boston’s early playoff ouster. Ryan wrote, “So the new coach says: ‘Look, Larry, you’re still Larry Bird, and nobody else is or is ever going to be. You’re going to be in the All-Star Game, you’re going to score 20, you’re going to lap the field in assists from the forward spot, and you’re still our key guy. But you don’t have to feel you’ve got to be the guy. Don’t ask too much of yourself. Don’t fight yourself, and don’t fight us.’”

While there’s considerable debate about what type of impact Bird will have on the Celtics in the 1990s, his super stardom throughout the 1980s is worth a first-class, rubber-stamp ticket to the Hall of Fame. Turn back the pages of Bird’s career, and you’ll find the remarkable story of a man who, along with Magic Johnson, took the NBA into a golden era. Never mind that Bird couldn’t run fast or jump high. What he could do was play a child’s game with intelligence, grace, and commitment, devoting long hours of practice to honing his skills on the court. “It’s the greatest job there is,” Bird says simply in explaining his unique work ethic.

Bird’s pro career began on a brisk fall night in 1979 when the Celtics, coming off a 29-53 year, opened their season at home against the Houston Rockets. During the pregame introductions, a flock of white birds was released in the Garden rafters to trumpet Bird’s arrival. Had the Celtics known then what they know now, something even more dramatic might have been arranged, like maybe a red carpet from Bird’s locker to the parquet floor.

Not that Bird was a sensation from the opening tipoff. Following that first game, Rocket forward Robert Reid was asked his impression of the rookie from Indiana State. “He wasn’t extraordinary,” Reid said. “Only Moses [Malone] is extraordinary.” But Reid and the rest of the world quickly came to learn that Bird would take a backseat to nobody.

Bird began to pile up impressive numbers, and the 1979-80 Celtics came out of the gate like the racehorse Secretariat in his prime. After a superb performance by Bird at Madison Square Garden, Fitch knew he had an all-time great on his hands. “I remember the New York media still gathered around Larry as we were ready to catch the bus back to the hotel,” Fitch recalls. “I just said, ‘Catch a cab, Rook,’ and I figured it was going to be that way. It was obvious that Larry Bird was something special.”

Where there was a Bird, could the championships be far behind? Boston won the title in 1981, thanks largely to a clutch three-point shot by Bird in the waning minutes of Game 6. Leading 3-2 in the series against Houston, the Celtics had built a 17 point-lead at the Summit. But Houston used the energy of its crowd to fight back to within three.

Enter Bird. Rearing up in the left corner, Bird popped in a three-pointer to bring the noise level down several decibels. Boston went on to prevail by 11, but Bird described the locker room celebration as his introduction to the true feeling of winning.

He would experience the ecstasy again in 1984, when the Celtics won a classic seven-game series against the Lakers. Many NBA observers feel it was that 1984 series—with Bird and Johnson at center stage—that lifted the NBA into primetime status.

Bird was unquestionably at the top of his game from 1984 through 1986, when he won the MVP award three consecutive times. When the Celtics went 40-1 at home in 1986 and then romped through the playoffs, Bird and company had their third title of the decade.

But the good times couldn’t roll forever. The tragic death of Len Bias, the foot elements of Bill Walton, and the defection of Brian Shaw to Europe for a season stunted Boston’s progress. Nearly four years have passed since the Celtics last appeared in the Eastern Conference finals, and there’s nothing Bird would like better than to bring the Celtics back to championship form.

Bird isn’t discouraged by the prophets of doom who feel a championship team cannot ride on a 34-year-old player’s shoulders. “I don’t get up every day and worry about what people say,” Bird says. “All I care about is playing basketball, doing my job the best I can, and trying to live with it.”

As the Celtics press onward with new director of operations, Dave Gavitt, and new coach, Chris Ford, legions of Celtics fans will be anxious to find out if Bird can lead the Green Machine to another NBA championship. In Boston, four years without a title represents quite a drought.

“If anybody can do it, it would be Larry Bird,” said Houston Rockets coach Don Chaney before this season. “He has had a year under his belt now after the heel surgery, and his intelligence and competitiveness will continue to make him a force to be reckoned with.

“I don’t think Larry will be as dominant as he was earlier, because of his age and the surgery. It’s tougher for him to beat people with fakes off the dribble. But he’ll use more picks and figure out a way to get from point A to point B just as effectively with assistance from his teammates. He won’t allow his game to suffer, because his mind will overcome what has happened to his body.”

The historians will note that Bird has overcome disappointment before. When the Celtics fell into disarray at the end of the 1982-83 season, losing 4-0 to Milwaukee in the Eastern Conference semifinals, Bird took that setback personally. He returned to French Lick, Ind., for a summer’s worth of exhaustive workouts. There were long distance runs at sunrise and countless hours of drills on an asphalt court. A year later, the Celts were champs again, and Bird was the MVP.

“I don’t think anybody has ever been more dedicated to the quest for excellence than Bird,” says Chaney. The Rockets coach should know. Chaney was with Boston in the last year of his pro career when Bird joined the Celtics.

“We knew he had a special gift right away, but it takes more than God-given talent to achieve the way Bird has,” Chaney says. “As that season unfolded, you saw that he was committed to improvement and blessed with a rare understanding of the nuances of the sport. We all thought, ‘This kid’s stock can only skyrocket.’”

Chaney believes Bird played through the mid-1980s at a level that almost transcended the game. “Bird, at that time, was to small forwards what Jordan is to big guards today,” Chaney says. “It’s a plateau where very few players have gone. Those guys have set the tone for their respective positions.”

One area that has always helped set Bird apart from other small forwards has been his proficiency as a foul shooter. He was even better at the line in 1989-90 (93.0 percent) than in his last year before the surgery (91.6 percent), and it had looked for a while as though Bird would break Calvin Murphy’s all-time record of 78 in a row. Ironically, Bird’s streak was snapped at 71 in Houston against the Rockets, Murphy’s former team, shortly after the all-star break. With Murphy looking on from the stands, Bird saw his attempt for No. 72 rattle out, while Murphy exchanged high fives with fans in the stands.

“Listen, if anybody could break my record, it would be Larry Bird,” Murphy says. “He has the basics and the mechanics. Larry and I did some good-natured kidding while he was chasing the record, but there’s a deep-felt respect. I felt honored that Bird was the guy coming after me.”

While Bird flourished at the line last year, it took until after the all-star break for him to reacquire his golden touch from the floor. In 32 of the opening 44 games, he scored fewer than his career average of 25 points. There were games when Bird fired at will, and other games when he seemed to pass up shots to make a point about Rodgers’ request for a balanced offense. When he kept moving the ball around the perimeter in an early season loss at Detroit, the media wanted to know why Bird wasn’t shooting. “I’m just a point forward,” Bird snapped.

Shooting difficulties for half a season and philosophical disagreements with the coach haven’t cropped up this year. Bird picked up where he left off in the second half of the 1989–90 season, and the supporting cast appears rejuvenated by the coaching change. The Celtics are gently passing the torch from the Kevin McHale-Dennis Johnson-Robert Parish trio to up-and-coming youngsters such as Shaw and Reggie Lewis in an effort to improve on last year’s 52 victories. But as long as Bird is around to hold things together, Boston has a chance.

“I would never count out any team that has a Larry Bird,” says Seattle coach K.C. Jones, who coached Bird during the forward’s best years. “I wouldn’t break up the team, because they are only old in certain places. If the veterans get the proper assistance from the young guys they’ve brought along, that team could climb another mountain.”

Some people are wondering if this season might be Bird’s last hurrah. He has been vague on when he might hang up his sneakers, but says, “I’m going to play until I feel I can’t contribute anymore and then get out.”

But whether the final curtain on Bird’s show comes down after one, two, or five more years, he’s certain to retire to Indiana duly cast as Larry the Legend. “The more he does from this point on, the more icing there will be on the cake,” Chaney says. “It’s really hard to compare players of different eras, but in the case of a Bird, you have to put him at the top of the list at his position and then argue about second place. He has been the thinking man’s player.”

Indeed he has. For 12 years, Bird has provided a clinic on the nuances of basketball. His instincts tell him when to throw the long pass, when to hit the cutter, and when to flash into the passing lanes for an attempted steal. He has shown, without a doubt, that James Naismith’s game isn’t only for those who can run like a deer or float through the air with the greatest of ease.

While others cringe at the possibility of taking a game-winning shot, Bird relishes the opportunity. He visualizes himself making that winning jumper, and more times than not, the dream has come true. “Larry is the only guy I always feared in a make-or-break situation,” says fellow superstar Magic Johnson. “It has been fun competing against him all these years, but it’s been painful, too. That man is something else. He is a great credit to the sport of basketball. There will never be another one quite like Larry Bird.”

Looking for the ideal forward? Take Larry Bird. And as the playoffs draw near, keep in mind this Bird is far from extinct.

[During the 1990-91 regular season, the Celtics won the Atlantic Division with the help of 19.4 points, 8.5 rebounds, and 7.2 assists per game from Bird, who, as mentioned above, was battling a bad back. Bird even willed himself to a 41-point gem against Indiana in the opening round of the playoffs. “That was one of the greatest, gutsiest performances I’ve even seen,” Boston coach Chris Ford said afterwards. But Bird (needing to spend a night in traction to rest his ailing back) and the Celtics then fell to the Pistons in the Eastern Conference semifinals. Bird would eke out one more NBA season in 1991-92, bad back and all, suiting up for just 45 games. But when healthy, Bird still would put up 20 points, nearly 10 rebounds, and about 7 assists per game. He retired at age 36, forever Larry the Legend.]