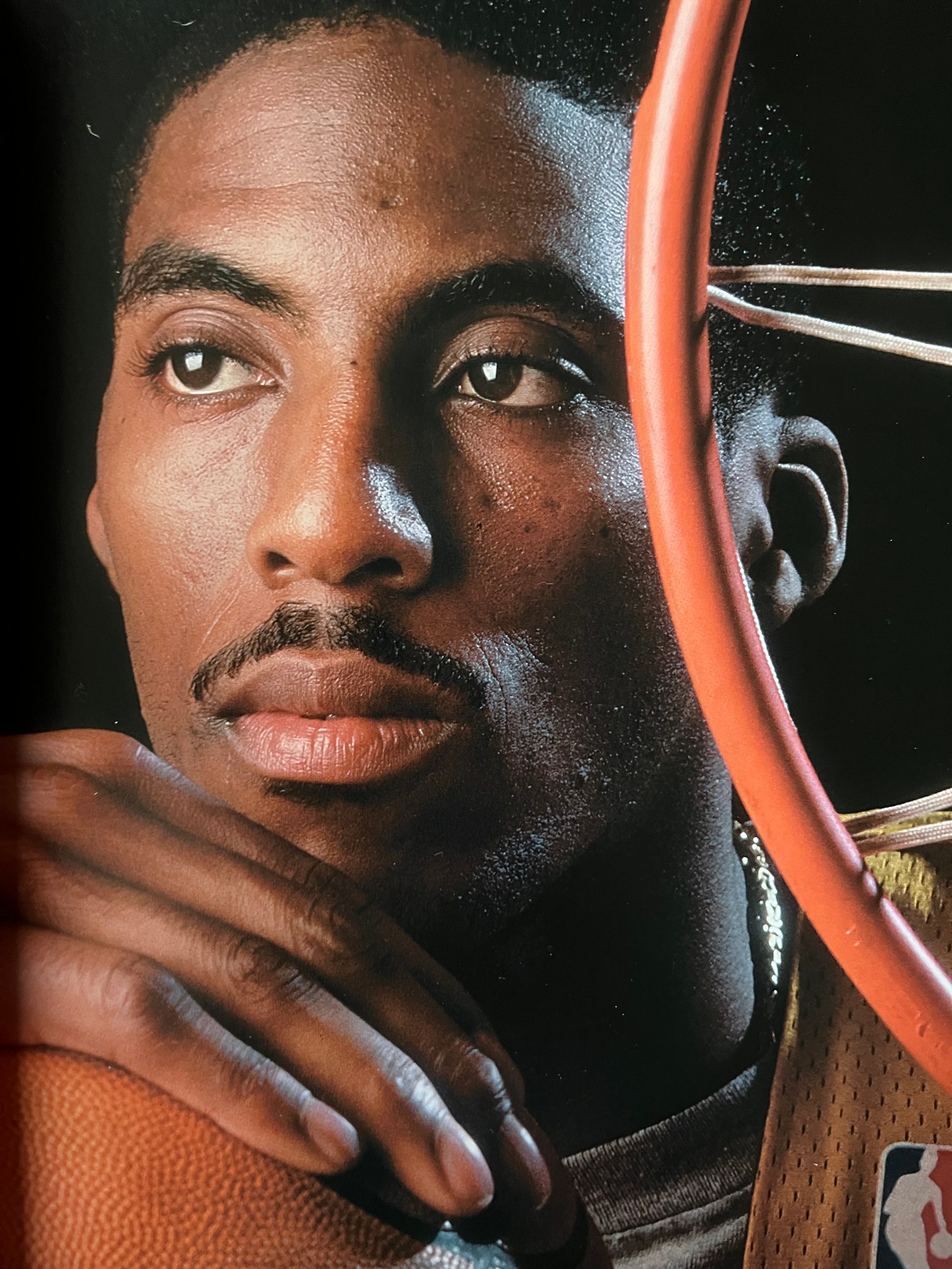

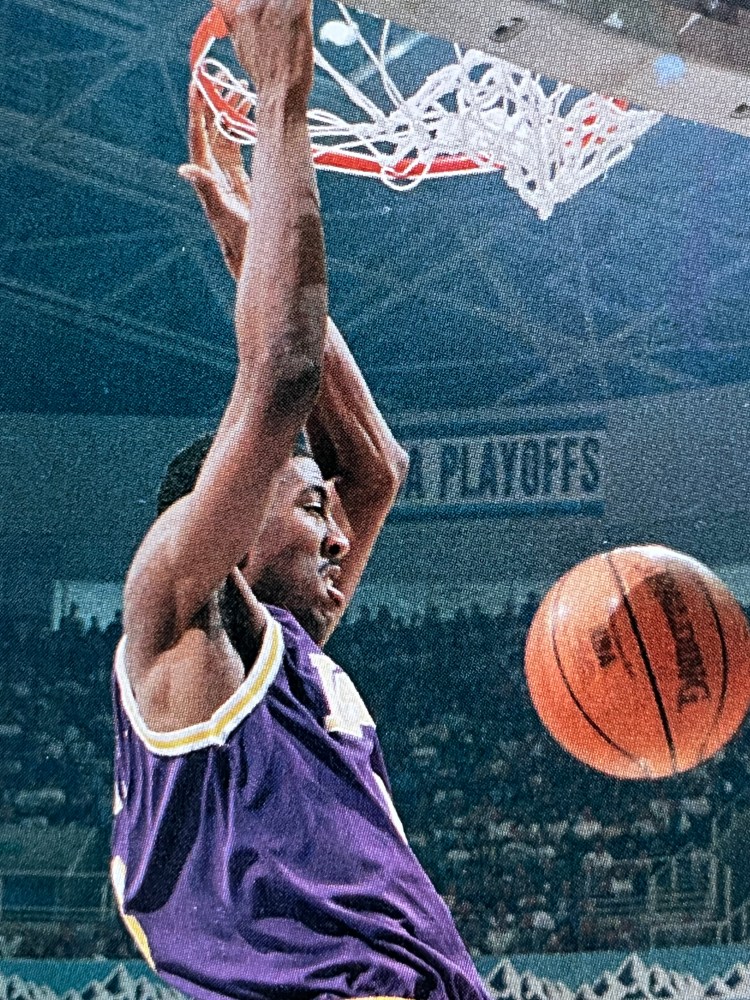

[Before Kobe Bryant’s rise to Laker fame and immortality, there was Eddie Jones. He was a mid-sized, ball-hawking, fleet-footed, floor-running complement to the paint-dominant Shaquille O’Neal. Jones sometimes thrived, sometimes struggled in his role as a featured Laker. As this article from The Sporting News’ 1997-98 Pro Basketball yearbook attests, some of Jones’ difficulties in L.A. (before being traded to Charlotte midway through the next season) likely owed in part to his reluctance to occupy the spotlight in Lakerland. Here’s more from the highly acclaimed Scott Howard-Cooper.]

****

It is a typical Saturday afternoon in Beverly Hills. Unfortunately “typical,” according to Lowell Moore, the man at the time entrusted with lining up promotions and endorsements for the Lakers’ reluctant hero, Eddie Jones.

An All-Star Game participant for the first time last February, Jones has come to Niketown, just down from Rodeo Drive, for an in-season autograph session with fans, the youngest of whom is literally positioned at his feet, or at least at the feet of the director’s chair in which Jones sits for a question-and-answer session. Jones has a smile that is quick and natural and a personality that is best described as laid back, so this day figures to be a layup. He can do this. It’s just that he’d rather not. Jones would prefer to be home. Watching TV, playing pool, hanging out with friends. Undergoing a root-canal procedure. Anything.

The star, sitting in the small second-floor VIP lounge stocked with snacks and friends and family along for the ride, is uneasy, but the crowd—waiting downstairs—is willing. The scene below is being broadcast on the wide screen TV in the room where Jones sips juice. The sounds break through the walls and up from the hardwood floors: “Ed-die! Ed-die! Ed-die!” the faithful chant, a familiar refrain from the Great Western Forum.

“Hear your theme song?” Moore says.

“Let’s do it,” Jones answers impatiently.

Within seconds, he is ready to walk down the flight of stairs. The emcee goes into the introductions, offering a résumé-in-Cliff Notes, how Jones starred at Temple, how he came to the Lakers as the 10th pick in the 1994 draft, and how that “was a great day for L.A.!”

“Let’s go,” Jones says.

He sound exasperated.

****

For years, before stardom had come to his doorstep and before it had been handled as if it were a ticking device. Eddie Jones enjoyed the benefit of obscurity. His toe-dip into football at age 9 lasted such a short time that it’s hardly worth mentioning, except that one day after getting drilled, he dropped his equipment on the field. Left it right there, the gear and any thoughts of a football career.

So it was on to basketball. Playing high school ball in the Fort Lauderdale suburb of Pompano Beach, Fla., and then for three seasons at Temple, brought some notoriety, but mostly it was a period of relative calm. Not counting, that is, the tough love of his coach and mentor, John Chaney, who is infamous for harangues directed at his players (all of his players).

Jones’ freshman year at Temple was lost to Proposition 48. But he took off from there, averaging 11.4 points off the bench as a sophomore and 17 points and seven rebounds the next season to help the Owls to the Elite Eight. After spending the summer of 1993 on the U.S. team that won the gold medal at the World Championships, Jones scored 19.2 points per game as a senior and was named the Atlantic 10 Conference’s Player of the Year.

The only lottery pick in Lakers history (another gold star for team executive vice president Jerry West), Jones was drafted after the likes of Donyell Marshall, Sharone Wright, Lamond Murray, Brian Grant, and Eric Montross. From there, he quickly won a spot in the starting lineup, beating out the more experienced and capable Anthony Peeler, then a berth in the NBA Rookie All-Star Game, where he won MVP honors. Coaches voted him to the All-Rookie Team at season’s end, after Jones had finished sixth in the NBA in steals and posted the league’s best steals-to-turnovers ratio.

In 1995-96, he was eighth in steals, joining Magic Johnson, Norm Nixon, and Sedale Threatt as the only players to lead the Lakers in that category in consecutive seasons. And, last season, marked by that all-star appearance in Cleveland, he ranked fourth in the league in steals and was the Lakers’ No. 2 scorer (at 17.2). For those in the know, his emergence was no real surprise.

After all, Jones was one of the best defensive guards in the league, even if he was very disappointed by his failure to make the NBA coaches’ All-Defensive Team. Jones, already well-regarded in the transition game, had progressed from a competent three-point shooter to a legitimate threat from behind the arc. In fact, he wound up 24th in the league in long distance, accuracy and tied an NBA record with multiple three-pointers in 22 consecutive games.

Given the opportunity to play with a center, who demanded so much defensive attention inside, Jones blossomed after the arrival of Shaquille O’Neal. “He always laid back the first couple years, trying to find his rhythm,” says Sacramento’s Mitch Richmond, another Fort Lauderdale-area product. “But with the acquisition of Shaq, you can see him being more aggressive.”

Jones was low-key, too, and that may have been important as well. “His game is rather stunning, but he lets his game do his talking,” Lakers coach Del Harris says. “And I think a lot of people appreciate that about Eddie. From that standpoint, he is old school. He is a guy who really just goes about his business playing the game. The flare he has comes in context. His dunks and steals are not something he goes out of his way to put any extra mustard on.”

Says West: “There are some very, very emotional players because of the nature of the league. Those other (more sedate) players seem to wear longer, particularly in the locker room environment and everything. Looking at him, you just feel like he’s going to get the same performance every night.

“He has a quieter personality, but he’s competitive. More important, he’s shown the willingness to play at that level and have that personality. Some guys’ personalities define what they do on the court. But most guys can’t back it up. It’s like their security blanket.”

Jones has a ready explanation for his approach to the game. “My time at Temple, that started it,” he says. “Coach Chaney never liked high fives, never liked any big show of emotion. I guess that just kind of rubbed off.”

Permanently.

“I’m not really embarrassed,” Jones says of all the attention he’s receiving. “I really appreciate it. I just don’t know how to handle it, I guess. People giving you things. All my life, I’ve had to work for things.”

****

There were, of course, no free rides with John Chaney, for whom crack-of-dawn practices often meant focusing on philosophy and life and not basketball. Taking shortcuts at Temple earned you a trip to the verbal woodshed—just as they do now, although the reaction today is on a different, lighter plane.

When Eddie Jones returns to Philadelphia, makes a weak attempt at acting “big league” by saying he’s not in the mood to sign autographs upon stopping by Chaney’s office, it naturally prompts Chaney to go off like an air-raid siren. Jones laughs, knowing he had successfully prodded the coach’s veins to come to attention and his eyes to come within a fraction of spilling out of their sockets. And then they sit down and go over Lakers game film from the just-completed season. The coach and player, who will turn 26 in October, remain very close.

Back in the days when the player who would become a standout defender was on the floor for the team whose reputation has long been about defense, Jones would be teased by Chaney about what he supposedly couldn’t do—he couldn’t stop this guy, couldn’t contain that guy. Chaney thought it would be fuel for extra motivation. He was right. Oh, was he. Jones took it as such a challenge that he defended with extraordinary, exuberance—and ended up in foul trouble. In this instance, more was less. Still, Jones was inspired to take his game to greater heights.

What always stayed with Jones was the Temple persona. Some guys in college get tattoos and big reputations; others, especially Owls, get Chaneys and low profiles (but solid instruction and guidance). So you can just imagine the hard time that comes with it being part of Nike’s advertising campaign and with endorsement deals with Sony and Top Dog sportswear, among others.

“I worry about that,” Chaney says. “He comes to me, he tells me often, ‘Coach, that’s not me. I’m the same guy. I’m not going to change.’ I tell him, ‘Eddie, you’re out there in Tinseltown. You can’t go to Heaven if you hold hands with the devil.’ He knows. He’s really ashamed of the spotlight.”

Says Moore, whose Successful Marketing Group no longer represents Jones, “It’s sometimes hard to figure out.”

And sometimes it isn’t.

“He is a reluctant star,” Moore says. “And maybe just a little concerned with losing his privacy. If I had to sit here and figure out a reason, that would be it. That he would lose his privacy. Yet other times, he’s sitting here asking what’s up with this project and what’s up with that project.

“It’s the most puzzling thing. It’s so different from when we first sat down with him (just before Jones came to Los Angeles) to now. For us, maybe it’s like we did our job too well. I don’t know what the answer is. I just don’t know.”

****

The Beverly Hills appearance is winding down, finally. E.J. Thigpen, visiting from Florida to see his stepson, senses Jones is nervous during the question-and-answer session because of the way he rushes his responses, at times practically running his words together. When the emcee announces that Jones will take time to speak to his fans before signing autographs, the crowd cheers wildly. But Jones’ chin drops to his chest.

Thigpen motions in Jones’ direction. “He’s got his head down,” Thigpen says, “so you won’t see the glow in his eyes.”

Jones is getting the star treatment, all right. People aren’t just waiting for autographs; they also wait to give him flowers or candy. They take photos, jockey for handshakes, ask for Eddie’s signature on balls and trading cards. There are jerseys galore—the No. 25 he wore in his first two seasons and the No. 6 he switched to in honor of idol Julius Erving, a move prompted by the Lakers’ retirement of Gail Goodrich’s No. 25. And there are jackets, pennants, photos, and caps. Even babies are present. Exactly when Jones declared his candidacy, for some office is not known.

Eddie Jones survives the event without too much difficulty—maybe because he isn’t even told about the strangest part, the photo op going on in the alley behind Niketown, until the next day. People were posing with his car, a white Mercedes, for photos.

“They were doing that?” he says. “For real?”

For real.

“I’m amazed now,” the reluctant star says.

It’s about time.